UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Tiendita Boricua Index

A Cultural Publication for Puerto Ricans La Tiendita Boricua Index Credits 2 Bombas 3 Dulce de Lechoza 3 Aguinaldos 4 Aguinaldos 5 José Feliciano – Feliz Navidad 6 Los Reyes 7 Rican Chef – Asopao de Pollo 8 Rican Chef – Pernil, Tembleque, Coquito 9 Música de Navidad to buy 10 Vicente Carattini - Música 10 Asómate al balcón para que veas esta parranda…. Asómate al balcón para que veas quien te canta Asómate al balcón pa’ que veas tus amigos Asómate al balcón pa; que veas que vacilón Feliz Navidad y Prospero Año Nuevo EL BORICUA and Staff DECEMBER 2008 DECEMBER 2008 EL BORICUA PAGE 2 ©1995-2008 - Editors and Contributors - All articles are the property of EL BORICUA or the property of its authors. Javier Figueroa - Dallas , TX Publisher Ivonne Figueroa - Dallas, TX Executive Editor & Gen. Mgr. Dolores Flores – Dallas, TX Language Editor Carmen Santos de Curran Food Editor & Wilfredo Santiago-Valiente Support Staff Executive Chef Contributing Editor Alisia Campos Thompson – Education Ramón Rodríguez Santiago – Tourism Miguel Santos Vélez -Resources Patricia Cintrón Alemán - Administration Nadia Alcalá – Legal Resources Fernando Alemán Jr - Web Consultant Special Thanks to . Tayna Miranda Zayas of Dra. Carmen S. Ortega Midge Pellicier MarkNetGroup.com PRIMOS Editor Contributing Editor George Collazo – PhotosofPuertoRico.com Advisory Panel Members Dolores M. Flores - Dallas Tommy Santoscoy - Orlando Anna Peña – San Antonio Charlie Rangel Dubois - NYC Antonio Pascual – San Francisco María Yisel Mateo Ortiz José Rubén de Castro Roger Zapata y Tol - Chicago Development Editor Photography Editor CarminaMost Colón back Duendeissues available - NYC Angel Canelo– in yearly – Houston CDRom Isabel Longoria Smidth - Denver Send your email to: elboricua_ email @ yahoo.com Website: http://www.elboricua.com WEBSITE Design courtesy of *MarkNet Group, Inc. -

La Voz December 2019

¡RODAR HAASTA $10K EN EFECTIVO! VIERNESES ENDICIEMBRE | 7PM &9& 9PM ¡Cinco afortunados ganadores serán seleccionadoos para jugar Rodar, Gira y Ganar Efectivo en los Días Festivos! Los LQYLWDGRVVHOHFFLRQDUiQ XQD GH ODV FLQFR ²FKDV GHO MXHJR TXH FRQWLHQHQFXDWUR SUHPLRV HQ HIHFWLYR TXH YDQ GHVGH $250 a $1,000,PiV XQD ²FKD GHQRPLQDGD ©%RQXV 5RXQGª Recibe UNA entrada de sorteo para lo siguiente: • 50 puntos ganados en juegos de tragamonedas o juegos de mesa • 500 puntos JDQDGRVHQ OD VDOD GH SyNHUª -XHJD\ JDQD OD URQGD GH ERQL²FDFLyQJDQD KDVWD $ 10,0000! GUNLAKECASINO.COM 6HUPD\RUHV GH DxRV \ WHQHU SDVDSRUWH \ XQD LGHQWL²FDFLyQ YiOLGD FRQ IRWR 'HEHQHVWDU SUHVHQWHV SDUD MXJDU &RQVXOWH HO &HQWUR GH 5HFRPSHQVDV R ZZZ JXQODNHFDVLQRFRPSDUD PiV GHWDOOHV *XQ /DNH 7ULEDO *DPLQJ $XWKRULW\ 7RGRVORV GHUHFKRV UHVHUYDGRV 6H DSOLFDQ RWUDV UHVWULFFLRQHV Betrayal of the Mexican American Student by Latino Teachers Traición del estudiante mexicoamericano por maestros latinos Many Mexican American professionals especially Hispanic educators, allegedly there to help. Sharing names would serve no those claiming roles in education have shirked the question purpose, other than force the guilty to run for cover and establish plausible de- of racism, as if doing so would make it go away. Their un- niability. I am not suggesting removal of pompous self-absorbed Hispanic pro- willingness to share their experiences of being discrimi- fessors with tenure. I am not suggesting restructuring, nor attacking the nated, profiled, and categorized left tremendous gaps in the existing education system. I am suggesting that all educational institutions preparation of new students now competing academically in designated as Hispanic-Serving Institutes, encourage their faculty to share their the top ten universities. -

Interview with MO Just Say

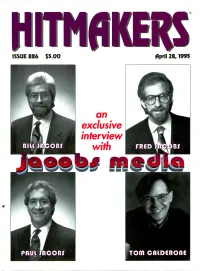

ISSUE 886 $5.00 flpril 28, 1995 an exclusive interview with MO Just Say... VEDA "I Saw You Dancing" GOING FOR AIRPLAY NOW Written and Produced by Jonas Berggren of Ace OF Base 132 BDS DETECTIONS! SPINNING IN THE FIRST WEEK! WJJS 19x KBFM 30x KLRZ 33x WWCK 22x © 1995 Mega Scandinavia, Denmark It means "cheers!" in welsh! ISLAND TOP40 Ra d io Multi -Format Picks Based on this week's EXCLUSIVE HITMEKERS CONFERENCE CELLS and ONE-ON-ONE calls. ALL PICKS ARE LISTED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER. MAINSTREAM 4 P.M. Lay Down Your Love (ISLAND) JULIANA HATFIELD Universal Heartbeat (ATLANTIC) ADAM ANT Wonderful (CAPITOL) MATTHEW SWEET Sick Of Myself (ZOO) ADINA HOWARD Freak Like Me (EASTWEST/EEG) MONTELL JORDAN This Is How...(PMP/RAL/ISLAND) BOYZ II MEN Water Runs Dry (MOTOWN) M -PEOPLE Open Up Your Heart (EPIC) BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN Secret Garden (COLUMBIA) NICKI FRENCH Total Eclipse Of The Heart (CRITIQUE) COLLECTIVE SOUL December (ATLANTIC) R.E.M. Strange Currencies (WARNER BROS.) CORONA Baby Baby (EASTWEST/EEG) SHAW BLADES I'll Always Be With You (WARNER BROS.) DAVE MATTHEWS What Would You Say (RCA) SIMPLE MINDS Hypnotised (VIRGIN) DAVE STEWART Jealousy (EASTWEST/EEG) TECHNOTRONIC Move It To The Rhythm (EMI RECORDS) DIANA KING Shy Guy (WORK GROUP) ELASTICA Connection (GEFFEN) THE JAYHAWKS Blue (AMERICAN) GENERAL PUBLIC Rainy Days (EPIC) TOM PETTY It's Good To Be King (WARNER BRCS.) JON B. AND BABYFACE Someone To Love (YAB YUM/550) VANESSA WILLIAMS The Way That You Love (MERCURY) STREET SHEET 2PAC Dear Mama INTERSCOPE) METHOD MAN/MARY J. BIJGE I'll Be There -

Cantemos a Coro

Cancionero Navideño Que la alegría, salud y paz reine en tu hogar en esta Navidad. Celebremos con la esperanza de un nuevo porvenir para todos. ¡Felicidades! 2 Índice de Canciones Bombas Puertorriqueñas COVID-19 3 Jardinero de cariño 18 De tierras lejanas 4 El Jolgorio 19 Levántate 4 Popurrí de Navidad 19 Si no me dan de beber 4 Traigo la salsa 20 Alegre vengo 5 Aires de Navidad 20 Caminan las nubes 5 Cantemos a coro 21 Cantares de Navidad 6 Casitas de las montaña 21 Pobre lechón 6 La escalera 22 El asalto 6 El cheque es bueno 22 El Santo Nombre de Jesús 7 Tu eres la causante de las penas mías 23 De la montaña venimos 7 Cuando las mujeres 23 Saludos, saludos 8 No quieren parranda, No quieren cantar 24 Venid pastores 8 Una noche en Borinquen / Desilución 24 A la zarandela 8 Canto a Borinquen 25 Alegría 9 Bombas 26 El fuá 9 Temporal 27 Noche de Paz 10 Cortaron a Elena 27 Feliz Navidad 10 Son Borinqueño 28 Venimos desde lejos 10 Medley de despedida 28 El Coquí 11 Dame la mano paloma 29 Mi Burrito Sabanero 11 Santa María 30 El Cardenalito 12 La suegra 30 A quién no le gusta eso 12 Asómate al balcón 31 Alegres venimos 12 Arbolito, arbolito 13 El ramillete 13 Parranda del sopón 13 El Lechón 14 Hermoso Bouquet 14 Los Peces en el Río 14 Niño Jesús 15 Yo me tomo el ron 15 Amanecer Borincano 16 La Botellita 16 Dónde vas María 17 Villancico Yaucano 17 Traigo esta trulla 18 3 Bombas Puertorriqueñas COVID-19 Compositor: Puerto Rico Public Health Trust Con la mascarilla bien puesta voy a celebrar la voy a utilizar de escudo para protegerme y a nadie -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Canciones Top 20 Anual

CANCIONES TOP 20 ANUAL - 2007 Pos Artista Título Sello Certificado 1 ALEJANDRO FERNANDEZ & BEYONCE AMOR GITANO SBM 8** 2 RIHANNA UMBRELLA UNI 8** 3 JENNIFER LOPEZ QUE HICISTE SBM 8** 4 SHAKIRA PURE INTUITION SBM 7** 5 JUANES ME ENAMORA UNI 6** 6 LA QUINTA ESTACION ME MUERO SBM 6** 7 RICKY MARTIN FEAT. LA MARI TU RECUERDO SBM 4** 8 ANTONIO CARMONA PARA QUE TU NO LLORES UNI 4** 9 KIKO & SHARA ADOLESCENTES SBM/PEP 4** 10 DANI MATA LAMENTO BOLIVIANO UNI/VAL 4** 11 ANDY & LUCAS QUIEREME SBM 3** 12 BEYONCE & SHAKIRA BEAUTIFUL LIAR SBM 3** 13 EL SUEÑO DE MORFEO PARA TODA LA VIDA WMG/GBM 3** 14 DAVID BISBAL TORRE DE BABEL UNI/VAL 2** 15 EL BARRIO BUENA, BONITA Y BARATA SEN 2** 16 LUCKY TWICE LUCKY UNI/VAL 2** 17 MELENDI ME GUSTA EL FUTBOL CAR/EMI 2** 18 MELENDI QUISIERA YO SABER CAR/EMI 2** 19 CONCHITA NADA QUE PERDER EMI 2** 20 EROS RAMAZZOTTI & RICKY MARTIN NO ESTAMOS SOLOS SBM 2** © Promusicae, listas elaboradas por Nielsen Soundscan Las listas se elaboran a partir de los datos facilitados por los siguientes sites/operadores: eMusic, iTunes, Movistar, MSN Music Club, MTV, Orange y Vodafone TONOS TOP 20 ANUAL - 2007 Pos Artista Título Sello Certificado 1 ALEJANDRO FERNANDEZ & BEYONCE AMOR GITANO SBM 16** 2 JENNIFER LOPEZ QUE HICISTE SBM 14** 3 LA QUINTA ESTACION ME MUERO SBM 12** 4 RIHANNA UMBRELLA UNI 10** 5 SHAKIRA PURE INTUITION SBM 10** 6 JUANES ME ENAMORA UNI 7** 7 ANTONIO CARMONA PARA QUE TU NO LLORES UNI 6** 8 KIKO & SHARA ADOLESCENTES SBM/PEP 5** 9 SHAKIRA LAS DE LA INTUICION SBM 5** 10 ANDY & LUCAS QUIEREME SBM 5** 11 DANI MATA LAMENTO BOLIVIANO UNI/VAL 5** 12 EL SUEÑO DE MORFEO PARA TODA LA VIDA WMG/GBM 4** 13 PIGNOISE TE ENTIENDO WMG/GBM 4** 14 EL ARREBATO HIMNO OFICIAL DEL SEVILLA F.C. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

LATIN SONGS 1 Ordered by TITLE SONG NO TITLE ARTIST 6412 - 05 100 Anos Maluma Feat

LATIN SONGS 1 Ordered by TITLE SONG NO TITLE ARTIST 6412 - 05 100 Anos Maluma Feat. Carlos Rivera 6331 - 04 11 PM Maluma 6292 - 10 1-2-3 El Simbolo 6314 - 11 24 de Diciembre Gabriel, Juan 6301 - 11 40 y 20 Jose Jose 6306 - 16 A Dios Le Pido Juanes 4997 - 18 A Esa Pimpinela 6310 - 20 A Gritos De Esperanza Ubago, Alex 6312 - 16 A Pierna Suelta Aguilar, Pepe 6316 - 09 A Puro Dolor Son By Four 5745 - 07 A Tu Recuerdo Los Angeles Negros 6309 - 01 Abrazame Fernandez, Alejandro 6314 - 12 Abrazame Muy Fuerte Gabriel, Juan 6310 - 18 Abusadora Vargas, Wilfrido 6317 - 08 Adios Martin, Ricky 6316 - 18 Adios Amor Sheila 6313 - 20 Adrenalina Wisin Feat. Jennifer Lopez & Ricky Martin 4997 - 11 Afuera Caifanes 6299 - 07 Ahora Que Estuviste Lejos Priscila 6299 - 11 Ahora Que Soy Libre Torres, Manuela 6311 - 16 Ahora Que Te Vas La 5a Estacion 6308 - 03 Ahora Quien (Salsa) Anthony, Marc 6304 - 06 Algo De Ti Rubio, Paulina 6297 - 07 Algo Esta Cambiando Venegas, Julieta 6308 - 08 Algo Tienes Rubio, Paulina 5757 - 04 Amame Martinez, Rogelio 6382 - 04 Amarillo Balvin, J 6305 - 04 Amiga Mia Sanz, Alejandro 6318 - 17 Amigos Con Derechos Maluma & Reik 6293 - 02 Amor A La Mexicana Thalia 5749 - 01 Amor Eterno Gabriel, Juan 5748 - 01 Amor Prohibido Selena 5756 - 01 Amor Se Paga con Amor Lopez, Jennifer 6312 - 01 Amor Secreto Fonsi, Luis 6304 - 08 Amor Sincero Fanny Lu 6297 - 02 Andar Conmigo Venegas, Julieta 6317 - 02 Andas En Mi Cabeza Chino & Nacho 6302 - 12 Angel De Amor Mana 6313 - 12 Aparentemente Vega, Tony 5753 - 02 Aprendiste a Volar Fernandez, Vicente 5751 -

Repertorio Tartara Clasif 2016

TARTARA SONG LIST ENGLISH MUSIC Artist Song ABBA Dancing Queen ACDC You Shook Me All Night Long All of me John Legend Aqua Barbie Girl Aretha Franklin Respect Arianna Grande Break Free Armin Van Buuren Going Wrong Avicci Wake Me Up Avril Lavigne Girlfriend Backstreet Boys Just Want You to Know Becky G Can´t Stop Dancing Bee Gees Saturday Night Fever Bee Gees Stayin Alive Bee Gees Bee Gees Medley Bill Haley & His comets Rock Around the Clock Billy Idol Dancing with Myself Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Black Eyed Peas The Time Bon Jovi It's My Life Bruno Mars Just The Way You Are Bruno Mars Up Town Funk Calvin Harris Feel So Close Calvin Harris Summer Calvin Harris How deep is your love Calvin Harris Sweet Nothing Carl Perkins Blue Suede Shoes Cher Believe Chuck Berry Johnny B Good Cindy Lauper Girls Just Wanna Have Fun Clean Bandit Rather Be Cold Play A Sky Full of Stars Come Fly With Me Michael Bubble Daft Punk Get Lucky Dave Clark Five Do You Love Me (Now That I Can Dance) David Getta Titanium David Getta Without you David Guetta & Chriss Willis Love Is Gone David Guetta Ft. Akon Sexy Bitch Diana Ross - Rupaul I will survive Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud Edward Maya Stereo Love Elvis Presley Have Some Fun Tonight Elvis Presley Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley Tutti Frutti Elvis Presley Blue Suede Shoes Endless Love Diana Ross & Lionel Riche Enrique Iglesias I Like It Enrique Iglesias Tonight I´Loving You Farrel Williams Happy Farruko Secretos Flo Rida Club Can't Handle Me Frank Sinatra Come fly With Me Frank Sinatra My way Frank Sinatra -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 09/04/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 09/04/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton My Way - Frank Sinatra Wannabe - Spice Girls Perfect - Ed Sheeran Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Broken Halos - Chris Stapleton Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond All Of Me - John Legend Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Don't Stop Believing - Journey Jackson - Johnny Cash Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Girl Crush - Little Big Town Zombie - The Cranberries Ice Ice Baby - Vanilla Ice Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Piano Man - Billy Joel (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Turn The Page - Bob Seger Total Eclipse Of The Heart - Bonnie Tyler Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Man! I Feel Like A Woman! - Shania Twain Summer Nights - Grease House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley At Last - Etta James I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor My Girl - The Temptations Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Jolene - Dolly Parton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Love Shack - The B-52's Crazy - Patsy Cline I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Let It Go - Idina Menzel These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon -

Yamaha – Pianosoft Solo 29

YAMAHA – PIANOSOFT SOLO 29 SOLO COLLECTIONS ARTIST SERIES JOHN ARPIN – SARA DAVIS “A TIME FOR LOVE” BUECHNER – MY PHILIP AABERG – 1. A Time for Love 2. My Foolish FAVORITE ENCORES “MONTANA HALF LIGHT” Heart 3. As Time Goes By 4.The 1. Jesu, Joy Of Man’s Desiring 1. Going to the Sun 2. Montana Half Light 3. Slow Dance More I See You 5. Georgia On 2. “Bach Goes to Town” 4.Theme for Naomi 5. Marias River Breakdown 6.The Big My Mind 6. Embraceable You 3. Chanson 4. Golliwog’s Cake Open 7. Madame Sosthene from Belizaire the Cajun 8. 7. Sophisticated Lady 8. I Got It Walk 5. Contradance Diva 9. Before Barbed Wire 10. Upright 11. The Gift Bad and That Ain’t Good 9. 6. La Fille Aux Cheveux De Lin 12. Out of the Frame 13. Swoop Make Believe 10.An Affair to Remember (Our Love Affair) 7. A Giddy Girl 8. La Danse Des Demoiselles 00501169 .................................................................................$34.95 11. Somewhere Along the Way 12. All the Things You Are 9. Serenade Op. 29 10. Melodie Op. 8 No. 3 11. Let’s Call 13.Watch What Happens 14. Unchained Melody the Whole Thing Off A STEVE ALLEN 00501194 .................................................................................$34.95 00501230 .................................................................................$34.95 INTERLUDE 1. The Song Is You 2. These DAVID BENOIT – “SEATTLE MORNING” SARA DAVIS Foolish Things (Remind Me of 1. Waiting for Spring 2. Kei’s Song 3. Strange Meadowlard BUECHNER PLAYS You) 3. Lover Man (Oh Where 4. Linus and Lucy 5. Waltz for Debbie 6. Blue Rondo a la BRAHMS Can You Be) 4. -

Sweet Adelines International Arranged Music List

Sweet Adelines International Arranged Music List ID# Song Title Arranger I03803 'TIL I HEAR YOU SING (From LOVE NEVER DIES) June Berg I04656 (YOUR LOVE HAS LIFTED ME) HIGHER AND HIGHER Becky Wilkins and Suzanne Wittebort I00008 004 MEDLEY - HOW COULD YOU BELIEVE ME Sylvia Alsbury I00011 005 MEDLEY - LOOK FOR THE SILVER LINING Mary Ann Wydra I00020 011 MEDLEY - SISTERS Dede Nibler I00024 013 MEDLEY - BABY WON'T YOU PLEASE COME HOME* Charlotte Pernert I00027 014 MEDLEY - CANADIAN MEDLEY/CANADA, MY HOME* Joey Minshall I00038 017 MEDLEY - BABY FACE Barbara Bianchi I00045 019 MEDLEY - DIAMONDS - CONTEST VERSION Carolyn Schmidt I00046 019 MEDLEY - DIAMONDS - SHOW VERSION Carolyn Schmidt I02517 028 MEDLEY - I WANT A GIRL Barbara Bianchi I02521 031 MEDLEY - LOW DOWN RYTHYM Barbara NcNeill I00079 037 MEDLEY - PIGALLE Carolyn Schmidt I00083 038 MEDLEY - GOD BLESS THE U.S.A. Mary K. Coffman I00139 064 CHANGES MEDLEY - AFTER YOU'VE GONE* Bev Sellers I00149 068 BABY MEDLEY - BYE BYE BABY Carolyn Schmidt I00151 070 DR. JAZZ/JAZZ HOLIDAY MEDLEY - JAZZ HOLIDAY, Bev Sellers I00156 072 GOODBYE MEDLEY - LIES Jean Shook I00161 074 MEDLEY - MY BOYFRIEND'S BACK/MY GUY Becky Wilkins I00198 086 MEDLEY - BABY LOVE David Wright I00205 089 MEDLEY - LET YOURSELF GO David Briner I00213 098 MEDLEY - YES SIR, THAT'S MY BABY Bev Sellers I00219 101 MEDLEY - SOMEBODY ELSE IS TAKING MY PLACE Dave Briner I00220 102 MEDLEY - TAKE ANOTHER GUESS David Briner I02526 107 MEDLEY - I LOVE A PIANO* Marge Bailey I00228 108 MEDLEY - ANGRY Marge Bailey I00244 112 MEDLEY - IT MIGHT