A Child-Driven Metadata Schema: a Holistic Analysis of Children's Cognitive Processes During Book Selection Jihee Beak University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kendriya Vidyalaya Sangathan, Ziet :: Mysore

प्रतिवेदन एवॊ सॊदर्भ तनदेशिका REPORT & REFERENCE MANUAL ऩु िकाऱयाध्यऺⴂ हेिु 21 ददवसीय सेवाकाऱीन ऩाठ्यक्रम 28 अगि से 17 शसि륍बर 2012 िक 21 Day In- Service Course for Librarians 28th August to 17th September 2012 ऩा腍मक्रभ एवॊ स्थर ननदेशक Course & Venue Director श्री एस. सेऱवराज Shri. S. Selvaraj ( उऩायक्ु ि, के . वव. सॊगठन तनदेिक, आॊचशऱक शिऺा एवॊ प्रशिऺण सॊथान मसै रू Deputy Commissioner, KVS Director, KVS ZIET, Mysore स्थरVenue के . वव. सॊगठन ,आॊचलरक लशऺा एवॊ प्रलशऺण सॊस्थान जी आई टी फी प्रेस कैम्ऩस , लसाथथनगय,भसै यू - 570011 Kendriya Vidyalaya Sangathan Zonal Institute of Education & Training GITB Press Campus, Siddharthnagar Mysore – 570011 Website: www.zietmysore.org ऩा腍मक्रभ सभन्वमक श्री वी. एऱ. वेरणेकर प्रशि. नािक (ग्रॊथाऱय अध्यऺ ) आॊचलरक लशऺा एवॊ प्रलशऺण सॊस्थान भैसूय Course Coordinator Vilas L Vernekar, Librarian, ZIET Mysore सॊसाधक डी.वव.एस समाभ कᴂ द्रीय वव饍याऱय १, ववजयवाडा मुजजब रदहमान के . यु कᴂ द्रीय वव饍याऱय, कजजजको蔼 Resource Persons Mr. D.V.S Sarma, Librarian , K.V No. 2 Vijayawada Mr. K.U Mujib Rahiman K.U, Librarian , K.V Kanjikode आॉ. शि. एवॊ प्रशि. सॊथान - सॊकाय ZIET Faculty श्री एम. रेड्डेजना नािको配िर शि. (र्गू ोऱ) Shri.M.Reddenna PGT (Geog.) श्री के . आ셂मगु म नािको配िर शि. (र्ौ. ववऻानॊ ) Shri.K.Armugam PGT ( Phys.) डॉ. एस. के . -

Employee Newsletter

ISSUE 1 Employee Newsletter KUTV, KMYU, KJZZ August 15, 2017 Kent’s Corner Hello Team! New Employees July 2017 Summer is coming to a close, and we have all been very busy during July and the first two weeks of August. As you know, we have finished Tamara Sanford | Producer up the July ratings period. We had some success and a few wins in the morning, and finished second in the evening newscasts. We certainly John Yelland | Web Producer have our work cut out for us with Fox bringing the tough competition in the morning and KSL being our strong competitor in the evening Hannah Knowles | Web Producer newscasts. Loren Brewer moved from PT Assignment Desk Editor to Early We have achieved our revenue budget for July and August for all our Morning News Producer combined TV stations. Our performance in the sales arena is clearly #1. Nathan Dowdle moved from Sports EP to Early Morning EP As you may know, this summer brought many employee changes to the station. We all know the only constant is change. This is one of my Ashley Beyer moved from Producer favorite quotes on change: “The pessimist complains about the wind; to Fresh Living Producer the optimist expects it to change; the realist adjusts the sails.” Matt Komma moved from Creative Services to Sports We are currently in the process of filling open positions at the station with an opening or two in each department. We also have moved current employees into new jobs. By promoting from within, the station and the employee are in a win-win situation. -

Applications of Social Research Methods to Questions in Information and Library Science

P1: JZP GNWD130-FM LU5031/Wildemuth Top Margin: 0.62733in Gutter Margin: 0.7528in April 20, 2009 21:24 APPLICATIONS OF SOCIAL RESEARCH METHODS TO QUESTIONS IN INFORMATION AND LIBRARY SCIENCE Barbara M. Wildemuth r Westport, Connecticut London iii P1: JZP GNWD130-FM LU5031/Wildemuth Top Margin: 0.62733in Gutter Margin: 0.7528in April 20, 2009 21:24 ii P1: JZP GNWD130-FM LU5031/Wildemuth Top Margin: 0.62733in Gutter Margin: 0.7528in April 20, 2009 21:24 APPLICATIONS OF SOCIAL RESEARCH METHODS TO QUESTIONS IN INFORMATION AND LIBRARY SCIENCE i P1: JZP GNWD130-FM LU5031/Wildemuth Top Margin: 0.62733in Gutter Margin: 0.7528in April 20, 2009 21:24 ii P1: JZP GNWD130-FM LU5031/Wildemuth Top Margin: 0.62733in Gutter Margin: 0.7528in April 20, 2009 21:24 APPLICATIONS OF SOCIAL RESEARCH METHODS TO QUESTIONS IN INFORMATION AND LIBRARY SCIENCE Barbara M. Wildemuth r Westport, Connecticut London iii P1: JZP GNWD130-FM LU5031/Wildemuth Top Margin: 0.62733in Gutter Margin: 0.7528in April 20, 2009 23:17 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wildemuth, Barbara M. Applications of social research methods to questions in information and library science / Barbara M. Wildemuth. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 978–1–59158–503–9 (alk. paper) 1. Library science—Research—Methodology. 2. Information science—Research—Methodology. I. Title. Z669.7.W55 2009 020.72—dc22 2008053745 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright C 2009 by Libraries Unlimited All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. -

The User Friendly Guide to INTERNET & COMPUTER TERMS

The User Friendly Guide to INTERNET & COMPUTER TERMS Charles Steed Gold Standard Press Inc. Reno, Nevada Copyright ã 2001 Charles Steed and Gold Standard Press Inc. Permission is granted to ALL USERS and readers to download, print and freely dis- tribute The User Friendly Guide To Internet & Computer Terms. No changes to this text is authorized. THIS TEXT MAY NOT BE SOLD EXCEPT BY AUTHORIZED AGENTS OR REPRESENTATIVES OF GOLD STANDARD PRESS INC. For information, contact Gold Standard Press Inc. 1475 Terminal Way, Suite E, Reno, Nevada 89502, tel. 360-482-2510. This book contains information gathered from many sources. It is published for gen- eral reference and not as a substitute for independent verification by users when circumstances warrant. It is sold with the understanding that neither the author nor publisher is engaged in rendering legal, psychological, accounting or professional advice. The publisher and author disclaim any personal liability, either directly or indirectly, for advice presented within. Although the author and publisher have used care and diligence in the preparation, and made every effort to ensure the accuracy and completeness of information contained in this book, we assume no responsibility for errors, inaccuracies, omissions, or any inconsistency herein. Any slights of people, places, publishers, books, or organizations are unintentional. The online version of this text has been slightly modified to faciliate easy download- ing. No significant differences from the printed version are present. Library of Congress -

Information Literacy : Navigating & Evaluating Today's Media

SEP 50554 “Information literacy” implies the ability to read and understand information. Now more than ever, such literacy skills are increasingly important—and more challenging to attain. Students must be able to identify, acquire, interpret, evaluate, organize, and share information. Information Literacy provides educators with . K–12 Grades • strategies and activities to help students achieve information literacy • guidelines for evaluating sources of information • tools for judging authenticity of data • insights to using information responsibly by citing sources and respecting copyrights • ideas on concept mapping, graphic organizing, and project-based learning Media Today’s & Evaluating Navigating Literacy Information • means to starting up and using blogs, wikis, podcasts, and more There are many exciting opportunities in this age of information—for those who are literate. Sara Armstrong, PhD, was a classroom teacher for 17 years, where she had the opportunity in the early 1980s to develop a telecommunications project using her 300-band modem and an Atari 800 computer. This interactive book talk with students at a school 200 miles away sparked a lifelong interest in putting students in touch with another through the use of technology. She especially hopes that exchanging ideas with others they normally wouldn’t meet will help students develop as global citizens and advocates for world peace. Armstrong is an associate of the Thornburg Center for Professional Development, a CUE Gold Disk winner, and a passionate advocate for meaningful teaching and learning. Through her organization, Sara Armstrong Consulting, she speaks and conducts workshops on topics that include information literacy, digital storytelling, project-based learning, multiple intelligences, and technology integration. -

Focus: HOPE PART II Page 1 Table of Contents Fiscal Year 2006

REPORT TO THE STATE OF MICHIGAN Fiscal Year 2006 Funding Center for Advanced Technologies First Step, Fast Track High School Program Submitted to the Michigan Legislature and the Michigan Department of Labor and Economic Growth [Page intentionally left blank] [Page intentionally left blank] Focus: HOPE PART II Page 1 Table of Contents Fiscal Year 2006 FOCUS: HOPE REPORT TO THE STATE OF MICHIGAN FISCAL YEAR 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Cover Letter (in report) II. Table of Contents III. Focus: HOPE Overview IV. Funded Programs - Program Report – Program Report - Fiscal Year 2006 – Response to Legislatively Requested Specifics V. Budget Report VI. Appendices A. Select Recognition and Citations B. Education Program Flow Chart – Focus: HOPE C. Campus Map D. Organizational Chart E. Board of Directors and Advisory Board F. CAT Associate and Bachelor Degree Curriculum G. CAT Academic Course Offerings Schedule H. Excerpts from Student Scholarship Essays I. Recruiting and Marketing Materials J. Professional Development and Job Fair Materials K. Partial List of Industry Partners That Have Hired Focus: HOPE Graduates L. Success Stories/Student Profiles M. Machinist Training Institute Curriculum Description and 2005-2006 Course Schedule N. First Step and FAST TRACK Curriculum Descriptions and 2005-2006 Course Schedule O. Information Technologies Center Program Materials P. Focus: HOPE Internet Site Web links for Kids Q. Focus: HOPE Revenue Chart R. Select Distinguished Visitors to Focus: HOPE S. Recent Articles and Other Information of Interest: • “Governor Appoints Keith Cooley Director of Department of Labor and Economic Growth, Robert Swanson to Retire in March” press release from the Office of the Governor, January 25, 2007 • “Focus: HOPE Board Appoints COO Duperron as Interim CEO, Forms Search Committee for Top Leadership Position” press release from Focus: HOPE, January 31, 2007 • “U.S. -

Online Safety and Media Sobriety Manual for Parents, Pastors, and Ministry Leaders

Online Safety and Media Sobriety Manual for Parents, Pastors, and Ministry Leaders www.safefamilies.org About this Manual, TechMission, and Safe Families Safe Families is a program of TechMission, Inc. that was formed to assist parents in protecting their children from pornography and other dangers on the Internet. TechMission started in 2000 with its first program, the Association of Christian Community Computer Centers (AC4) with the goal addressing the digital divide, which is the gap between those who have access and training with computers and those without. AC4 is the largest association of faith-based community computer centers in the world with over 500 member serving over 50,000 individuals each year. As AC4 assisted in getting people across the digital divide, it became clear that it was one thing to get people across the digital divide, but it was another thing to get them across safely. Our vision for AC4 is "Computer Skills to Make a Living—A Spiritual Foundation to Make a Life." With many low-income families buying their first computer second-hand for $50, it is not reasonable to expect them to pay another $50 for Internet filtering software. Because of this, Safe Families has committed to distributing over 100,000 copies of free Internet filtering software in the next year. As we move into the information age, society is experiencing changes unlike ever before. We believe that it is important for all individuals to take an active role in addressing the social issues of the information age (like the digital divide) as well as the moral issues (like online safety and media sobriety). -

The Facts on File Guide to Research

term paper, or written project depends not only on the quality of your writing but THEalso on the FACTS quality of your ON research. FILE With the vast explosion in growth of electronic GUIDEtechnology, TOvirtual RESEARCH libraries, the Internet, and traditional libraries, re- term paper, or written project depends not only on the quality of your writing but also on the quality of your research. With the vast explosion in growth of elec- THEtronic technology, FACTS virtual libraries, ON the Internet,FILE and traditional libraries, researching any topic has never GUIDEbeen easier than itTO is today, RESEARCH so long as you understand JEFF LENBURG THE FACTS ON FILE GUIDE TO RESEARCH Copyright © 2005 by Jeff Lenburg All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lenburg, Jeff. The Facts On File guide to research / by Jeff Lenburg. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-5741-9 (acid-free paper) 1. Information retrieval—Handbooks, manuals, etc. 2. Research— Methodology—Handbooks, manuals, etc. 3. Library research—Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Title. ZA3075.L46 2005 025.5'24—dc22 2004018941 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. -

Increasing Your Mathematics and Science Content Knowledge

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 466 356 SE 066 051 , AUTHOR Thorson, Annette, Ed. TITLE Increasing Your Mathematics and Science Content Knowledge. INSTITUTION Eisenhower National Clearinghouse for Mathematics and Science Education, Columbus, OH. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. REPORT NO ENC-02-003 PUB DATE 2002-07-00 NOTE 93p.; Theme issue. Published quarterly. CONTRACT RJ97071001 AVAILABLE FROM Eisenhower National Clearinghouse for Mathematics and Science Education, 1929 Kenny Road, Columbus, OH 43210-1079. Tel: 800-621-5785 (Toll Free);'Fax: 614-292-2066;e-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://www.enc.org. PUB TYPE Collected Works - Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT ENC Focus; v9 n3 Jul 2002 EDRS PRICE MFOl/PCO4 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Elementary Secondary Education; *Faculty Development; *Instructional Materials; Integrated Curriculum; *Knowledge Base for Teaching; *Mathematics Education; *Science Education ABSTRACT This journal is intended for classroom teachers and provides a collection of essays and instructional materials organized around the theme of mathematics and science content knowledge. Articles include: (1) Itwatching Ourselves Learn" (Annette Thorson); (2) Itsearch Smarter!" (Kimberly S. Roempler); (3) "Teacher Education Materials Projectt1(Joan Pasley and Thomas Gadsden) ; (4) '#ResearchingNew Ways To Serve You!1t (Annette Thorson); (5) "Teachers Need a Special Type of Content Knowledgeu1(Zalman Usiskin) ; (6) "DO Not Forget Yourself as a Teacher of Yourselfo1(Terese Herrera); (7) "A Deeper Look at Elementary Mathematics" (Melanie Shreffler); (8) I1Staying a Step Ahead" (Pamela Galus); (9) "ENC Can Help You Increase Your Content Knowledge" (Judy Spicel: and Laura K. Brendon); (10) I1Basic Skills and Conceptual Understanding: It's Not Either/Or" (Joan M. -

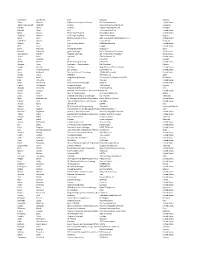

First Name Last Name Title Company Country Carlos Abascal Business

First Name Last Name Title Company Country Carlos Abascal Business Development Director Ole Communications United States Ashraff Reza Anand Abdullah Director Antenna International Pte Ltd Singapore Patricia Abreu Director Upstar Comunicações, SA Portugal Manuel Abud CEO TV Azteca SAB DE CV United States David Acosta Senior Vice President City National Bank United States Adebayo Adebiyi Chief Exective Officer Telly 4 Africa Media Nigeria Marie Adler CEO/Founder/Chairman Adler & Associates Entertainment, Inc. United States Jose Maria Aguero CEO Grupo Nacion Paraguay William Airy Chief Strategy Officer LeSEA Broadcasting United States Rod Aissa EVP Oxygen United States David Albareda Managing Director Devised TV Spain Hamed Alghamdi general manager Ien TV / Ministry of Education Saudi Arabia Abdulwahab Alshehri Program supervisor iEN TV ,Ministry of Education Saudi Arabia Stuart Alson President ITN Distribution, Inc. United States Ana Alvarado VP ECUAVISA Ecuador Adolfo Alvarez VP On Air Programming ¡HOLA! TV United States Georges Amar Realisateur - Coordonateur CBC Montreal Canada Joseph Amodei President Virgil Films and Entertainment United States Javier Anaya Gutierrez Sub-Director Claro video, Inc. United States Jason Andreacci Director, Content Technology ION Media Networks United States Loreto Araya President PROVOZ CHILE Chile Karina Arbizu Programming Manager Telecorporacion Salvadoreña (TCS) El Salvador Dale Ardizzone COO INSP, LLC United States Greg Armstrong President/General Manager KCDO-TV United States Hector Arosemena Content Manager TVN Panamá Panama Gonzalo Arrisueño Programming Manager Telefonica Peru Peru Jimmy Arteaga President of Programming, Promotion & WAPAProduction TV United States Carola Arze Head of Programming Red Uno de Bolivia S.A. Bolivia Jose C. Aznar P. Schedule and Adquisition Manager Sun Channel Venezuela Edita Babakhanyan Sr.