Principle 8-9 Full with Index New Hebrew.Qxp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Sample of This Item

Praise for Turning Judaism Outward “Wonderfully written as well as intensely thought provoking, Turning Judaism Outward is the most in-depth treatment of the life of the Rebbe ever written. !e author has managed to successfully reconstruct the history of one of the most important Jewish religious leaders of the 20th century, whose life has up to now been shrouded in mystery. A compassionate, engaging biography, this magni"cent work will open up many new avenues of research.” —Dana Evan Kaplan, author, Contemporary American Judaism: Transformation and Renewal; editor, !e Cambridge Companion to American Judaism “In contrast to other recent biographies of the Rebbe, Chaim Miller has availed himself of all the relevant textual sources and archival docu- ments to recount the details of one of the more fascinating religious leaders of the twentieth century. !rough the voice of the author, even the most seemingly trivial aspect of the Rebbe’s life is teeming with interest.... I am con"dent that readers of Miller’s book will derive great pleasure and receive much knowledge from this splendid and compel- ling portrait of the Rebbe.” —Elliot R. Wolfson, Abraham Lieberman Professor of Hebrew and Judaic Studies, New York University “Only truly great biographers have been able to accomplish what Chaim Miller has with this book... I am awed by his work, and am now even more awed than ever before by the Rebbe’s personality and prodi- gious accomplishments.” —Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Hersh Weinreb, Executive Vice President Emeritus, Orthodox Union; Editor-in-Chief, Koren-Steinsaltz Talmud “A fascinating account of the life and legacy of a spiritual master. -

00 FRONT MATTER FINAL.Indd

THEtorah FIVE BOOKS of MOSES WITH COMPLETE HAFTARAH CYCLE THEtorah FIVE BOOKS of MOSES WITH COMPLETE HAFTARAH CYCLE with reflections and inspirations compiled by RABBI CHAIM MILLER from hundreds of Jewish thinkers, ancient to contemporary THE GUTNICK LIBRARY The SLAGER EDITION of JEWISH CLASSICS First Edition First impression . November 2011 Torah — The Five Books of Moses With Complete Haftarah Cycle with reflections and inspirations compiled by Rabbi Chaim Miller from hundreds of Jewish thinkers, ancient to contemporary ISBN 13: 978-1-934152-26-3 ISBN 10: 1-934152-26-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2011920491 © Copyright 2011 by Lifestyle Books Published and Distributed by: Lifestyle Books 827 Montgomery Street, Brooklyn, N.Y. 11213 For orders: 1-888-580-1900 718-951-6328 Fax: 718-953-3346 www.lifestylebooks.org e-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the copyright holder, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper or broadcast. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Gefen Publishing House in the preparation of parts of the Hebrew text. TABLE of CONTENTS ........................................... xi Introduction LEVITICUS PARASHAH HAFTARAH Transliteration rules .............................. xxi Va-Yikraʾ ............................................ 590 ......... 1344 ............... xxiii Blessings on reading the Torah Tzav .................................................. -

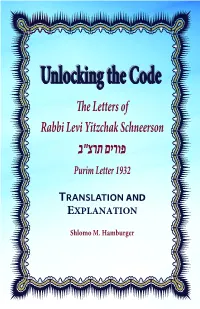

6Ompdljoh Uif $Pef

ćJT$IBG"W+PVSOBM $IBG"W+PVSOBM JTEFEJDBUFEUP #BSCBSB-'SVNLJO Đ"Ğ ĘĤĞč Ħč ĐėĤč Ĕ"ĞĥĦ Ĕčĥ Č"ė 'ĠĜ 6OMPDLJOHUIF$PEF +FSPNF.'SVNLJO ćF-FUUFSTPG Đ"Ğ ĘďĜĞĚ đĐĕĘČ ěč ĤĕČĚ ĐĕĘďĎ Ĕ"ĝĥĦ čČ đ"Ĕ 'ĠĜ 3BCCJ-FWJ:JU[DIBL4DIOFFSTPO +PFM*)BNCVSHFS Đ"Ğ ĘČĤĥĕ ěč ğĝđĕ ē"ĝĥĦ čČ č"ė 'ĠĜ 53"/4-"5*0/8*5) 13"$5*$"- - &440/4 #Z 1BVM.)BNCVSHFS 4IMPNP.PSEFDIBJ)BNCVSHFS BOE/BODZ-'SVNLJO Ĥ"ĝč To download a copy of this publication, go to www.theanochiproject.com Shlomo M. Hamburger is a partner in a large international law firm. He is the author of numerous books and articles and a frequent speaker and teacher on employee benefit matters. Shlomo is on the International Advisory Board for Chabad on Campus International and an active member of the Chabad Shul of Potomac, Maryland. © Copyright 2019 by Shlomo M. Hamburger Published by | 3 UNLOCKING THE CODE : The Letters of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson Translation with practical lessons PREFACE ___________ Several months ago, I was speaking with a Chabad shliach. I mentioned that I had been studying some of the letters of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak, father of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson. I asked him whether he had studied the letters. He said that he did review them when he was in yeshivah but not recently. “They are written in code,” he explained. Since that conversation, I decided to try to unlock the code as it were. Are the letters deep and filled with unidentified Kabbalistic and other references? Absolutely. -

Attitudes Toward the Study of Zohar and Lurianic Kabbalah, from the Dawn of Chasidism to Present Day Chabad

57 Attitudes toward the Study of Zohar and Lurianic Kabbalah, from the Dawn of Chasidism to Present Day Chabad By: CHAIM MILLER In the contemporary Chabad community, study of the primary texts of Kabbalah is not emphasized. Chabad Chasidic thought (Chasidus) is studied extensively, as are the sermons (sichos) of the Lubavitcher Reb- bes, texts that themselves are rich in citations from, and commentary on, Kabbalistic sources. However, for reasons I will explore in this essay, Kabbalah study from primary texts, such as the Zohar and works of Rabbi Yitzchak Luria (Arizal), is relatively uncommon in Chabad. This has been noted by the Seventh Lubavitcher Rebbe himself: “Generally speaking, Kabbalah study was not common, even among Chabad Chasidim.”1 Is this omission intentional, a matter of principle? Or is Kabbalah study deemed worthwhile by Chabad, but neglected merely due to the priority of other activities? 1 Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, Toras Menachem, Hisvaduyos 5745 (Vaad Hanachos Lahak, 1985) volume 2, p. 1147. The Rebbe stressed that “Kabbalah study was not common, even among Chabad Chasidim” since, of the various strands of Chasidic thought, Chabad Chasidus is particularly rich in its use of Kabbalistic sources (see below section “Lurianic Kabbalah in Early Chabad”). One might therefore expect that Chabad Chasidim in particular might be in- clined to Kabbalah study. Rabbi Chaim Miller was educated at the Haberdashers’ Aske’s School in London, England and studied Medical Science at Leeds University. At the age of twenty-one, he began to explore his Jewish roots in full-time Torah study. Less than a decade later, he published the best-selling Kol Menachem Chumash, Gutnick Edition, which made over a thousand discourses of the late Lubavitcher Rebbe easily accessible to the layman. -

The Hertog Study CHABAD on CAMPUS

The Hertog Study CHABAD ON CAMPUS Mark I. Rosen, Steven M. Cohen, Arielle Levites, Ezra Kopelowitz This study was commissioned and funded by the Hertog Foundation © 2016 Hertog Foundation Inquiries about the study should be directed to: Mark I. Rosen Associate Professor Hornstein Jewish Professional Leadership Program Brandeis University Waltham, MA 02453 [email protected] 781-736-2132 Copies of this report may be downloaded at http://bjpa.org/Publications/details.cfm?PublicationID=22580 Cover photo credit: Ucumari Photography (Flickr Creative Commons) Kenneth Snelson Needle Tower, 1968 Smithsonian Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Report design by: Jessica Tanny The Hertog Study CHABAD ON CAMPUS Mark I. Rosen Steven M. Cohen Arielle Levites Ezra Kopelowitz September 2016 CONTENTS, FIGURES, AND TABLES CONTENTS 11 Executive Summary 19 Chapter 1: Studying Chabad on Campus 19 Introduction 20 The Recent Growth of Chabad on Campus 20 An Overview of Chabad on Campus 24 Research Questions and the Organization of This Report 25 Study Methodology 25 The Role of Hillel in the Study 27 Chapter 2: Who Comes to Chabad on Campus? 27 Students’ Jewish Backgrounds and Campus Jewish Life 28 Jewish Upbringing and Pre-College Jewish Experiences 32 Patterns of Participation at Jewish Organizations During College 36 Political Orientation and Participation at Chabad 37 Welcoming, Attraction, and Avoidance Contents, Figures, and Tables 6 45 Chapter 3: What Is the Nature of Chabad’s Work with Students on Campus? 45 The Work of Chabad: Operating Principles -

Unlocking the Code E Letters of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson ב"צרת

UNLOCKING THE CODE e Letters of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson Translations with Practical Lessons Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson was the father and teacher of Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson, the seventh Lubavitcher Rebbe. For about 25 years, the Rebbe lived, for the most part, in his parents’ home where UnlockingUnlocking thethe CodeCode the Rebbe and his father developed a close personal bond. e Rebbe and his father last saw each other in the fall of 1927 (29 Tishrei 5688) and would never see each other again in the physical world. During 1928, and pending the Rebbe’s wedding date, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak wrote a series of letters to his son all related to the Rebbe’s upcoming e Letters of wedding. Four of the letters were written on the eve of Passover, Shavuot, Rosh Hashanah, and Sukkot. In each letter, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak tied the holiday to his son's upcoming wedding through Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson explaining the Kabbalistic signicance of each holiday and how it relates to different aspects of marriage. ese letters show not just פורים תרצ"ב Torah insights but also very personal insights into the close connection between Rabbi Levi Yitzchak (the then 50-year old father) and the Rebbe (his then 26-year old son). Purim Letter 1932 “It is my obligation and great zechus to suggest, request, etc., that everyone study from {my father’s} teachings…” From a letter of the Rebbe, Motzei Tisha B’Av 5744 (1984). TRANSLATION In this publication, Shlomo M. Hamburger translates and analyzes AND these four letters. In addition, Mr. -

Toldos Hadassah Rashi.Qxd

p a r s h a s T o l d o s ,usku,[ ,arp [ The Name of the Parsha [ n the words, These are the descendants (Toldos) of inferior one. Rather, it is the Jewish body which appears O Yitzchak, Rashi comments that, these are Yaakov to be quite similar to that of the non-Jew, that was and Eisav mentioned in the Parsha. selected by God (See Tanya ch. 49). ccording to Chasidic teachings, Yaakov represents Of course, this does not mean to say that the soul was A the soul, and Eisav, the body. The Parsha is thus not chosen by God at all. It is only that the body has no named after both Yaakov and Eisav, because the soul and redeeming feature of its own other than the fact that it was the body each have their own exclusive qualities. chosen by God so its chosenness stands out more The soul is described as a child of God, because the than in the case of the soul. love shared between the soul and God is a natural type of When soul and body are together, each begins to learn love, resembling the parent-child relationship. from the others unique quality: Through observing Torah The body, on the other hand, has no inherent love for and mitzvos, the soul teaches the body how to love God; God on the contrary, it conceals Gods presence. But, the body, in turn, teaches the soul how to reveal its ironically, when God chose the Jewish people, He chosenness. chose primarily our bodies. -

1 ARIZAL HAGADAH FRONT MATTER.Indd

vdsv ak pxj ak vdsv haaggaaahggaaah T HHEE KOOLL M EENACHEMNAC H E M H AAGGADAHG GA DA H T HHEE S LLAGERA G E R E DDITIONI T I O N With commentary and insights anthologized from Classic Rabbinic Texts and the works of the Lubavitcher Rebbe Compiled and Adapted by Rabbi Chaim Miller The Gutnick Library of Jewish Classics THE KOL MENACHEM HAGGADAH with commentary from classic Rabbinic texts, and the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneersohn. ISBN-13: 978-1-934152-12-6 ISBN-10: 1-934152-12-9 © Copyright 2008 by Chaim Miller Published and Distributed by: Kol Menachem 827 Montgomery Street, Brooklyn, NY 11213 1-888-580-1900 1-718-951-6328 1-718-953-3346 (Fax) www.kolmenachem.com [email protected] First Edition — March 2008 Three impressions . March — April 2008 Fourth impression . January 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the copyright holder, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper or broadcast. Kol Menachem is a not-for-profit organization. Proceeds from the sales of books are allocated to future projects. בהזמנות לפנות: ”חיש“ — הפצת המעיינות, כפר חב”ד טל’: 03-9600770 פאקס: 03-9606761 [email protected] www.chish.co.il היכל מנחם, ירושלים, רחוב ישעיהו 22 טל': 02-5384928, פאקס 02-5385015, ת.ד. 5955 [email protected] ENGLAND & EUROPE: MENDEL GORMAN [email protected] AUSTRALIA: GOLD’S: 95278775 OR SHAUL ENGEL: 0438260055 SOUTH AFRICA: [email protected] • 0117861561 Dedication of the kol menachem haggadah The Kol Menachem Haggadah is dedicated to our dear friends D A V I D & L A R A S L A G E R and their children Hannah and Sara Malka N EW Y ORK / LONDON May the merit of spreading words of Torah illuminated by the teachings of Chasidus to thousands across the globe be a source of blessing for them and their family for generations to come. -

JPSGUIDE.Pdf

Bible 5/19/08 4:59 PM Page i JPS GUIDE THE JEWISH BIBLE Bible 5/19/08 4:59 PM Page ii The JPS Project Team Project Editor and Publishing Director Carol Hupping Assistant Editor Julia Oestreich Managing Editor Janet Liss Production Manager Robin Norman Researcher and Writer Julie Pelc Copyeditor Debra Corman Project Advisory Board Shalom Paul Fred Greenspahn Ziony Zevit Bible 5/19/08 4:59 PM Page iii JPS GUIDE THE JEWISH BIBLE 2008 • 5768 Philadelphia The Jewish Publication Society Bible 5/19/08 4:59 PM Page iv JPS is a nonprofit educational association and the oldest and foremost publisher of Judaica in English in North America. The mission of JPS is to enhance Jewish culture by promoting the dissemination of religious and secular works, in the United States and abroad, to all individuals and institutions interested in past and contemporary Jewish life. Copyright © 2008 by The Jewish Publication Society First edition. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, except for brief passages in connection with a critical review, without permission in writing from the publisher: The Jewish Publication Society 2100 Arch Street, 2nd floor Philadelphia, PA 19103 www.jewishpub.org Design and Composition by Masters Group Design Manufactured in the United States of America 08 09 10 11 12 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data JPS guide : the Jewish Bible. -

Front Matter for Haftaras.Qxd

vpyru, H A F T A R O S According to Chabad, Ashkenazic and Sefardic custom with a Commentary anthologized from Classic Rabbinic Texts and the works of the Lubavitcher Rebbe Compiled and Adapted by Rabbi Chaim Miller First Edition . September 2006 CHUMASH - BOOK OF HAFTAROS with commentary from Classic Rabbinic Texts and the Lubavitcher Rebbe ISBN 1-934152-00-5 © Copyright 2006 by Chaim Miller Published and Distributed by: Kol Menachem 827 Montgomery Street, Brooklyn N.Y. 11213 For orders tel: 1-888-580-1900 718-951-6328 Fax: 718-953-3346 www.kolmenachem.com e-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the copyright holder, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper or broadcast. [ Contents Preface . .ix Introduction to the Public Torah and Haftarah Reading . .xiii Cantillation Marks . .xxvi [ G E N E S I S / ,hatrc Metzora . .65 [ S P E C I A L O C C A S I O N S Acharei . .67 Bereishis . .4 Shabbos Erev Rosh Chodesh 119 Kedoshim . .68 Noach . .7 Shabbos Rosh Chodesh . .121 Emor . .71 Lech Lecha . .9 Public Fast . .140 Vayeira . .11 Behar . .73 Rosh Hashanah (Day 1) . .166 Chayei Sarah . .14 Bechukosai . .75 Rosh Hashanah (Day 2) . .170 Toldos . .16 Shabbos Shuvah . .114 Vayeitzei . .18 [ N U M B E R S / rcsnc Yom Kippur (Morning) . .172 Vayishlach . .22 Bamidbar . .76 Vayeishev . .24 Naso . .78 Yom Kippur (Afternoon) . .175 Mikeitz . .26 Beha’aloscha . -

Shluchim to the Frontline Town of S'derot a Daily Dose

contents WHY THE EMPHASIS ON G-D’S CHARIOT? 3 G-D HIMSELF WAS REVEALED! (CONT.) D’var Malchus | Likkutei Sichos Vol. 37, pg. 79-84 SHLUCHIM TO THE FRONTLINE TOWN 7 OF S’DEROT Special Report A DAILY DOSE OF MOSHIACH 10 Moshiach & Geula THE REBBE ON THE PRINCIPLES OF 14 FAITH: A ‘SHULCHAN ARUCH’ OF EMUNA Feature | Avrohom Rainitz USA MIVTZA T’FILLIN: 40 YEARS – 40 744 Eastern Parkway 22 Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409 STORIES Tel: (718) 778-8000 Mivtzaim | Shneur Zalman Berger Fax: (718) 778-0800 [email protected] www.beismoshiach.org OUR REBBEIM ON ZIONISM AND THE 29 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: MEDINA M.M. Hendel Shleimus HaAretz | Rabbi Yaakov HaLevi Horowitz ENGLISH EDITOR: Boruch Merkur; THE SIX DAY WAR PROPHECY [email protected] Feature| Menachem Ziegelboim HEBREW EDITOR: 32 Yaakov Chazan; [email protected] Beis Moshiach (USPS 012-542) ISSN 1082- A WOMAN OUT OF THE LEGENDS 0272 is published weekly, except Jewish 37 holidays (only once in April and October) for (CONT.) $130.00 in Crown Heights, $140.00 in the Profile | Ofra Badusa USA & Canada, all others for $150.00 per year (45 issues), by Beis Moshiach, 744 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409. THE SECRET POWER OF THE SHLUCHIM Periodicals postage paid at Brooklyn, NY and 41 Shlichus| Rabbi Yaakov Shmuelevitz additional offices. Postmaster: send address changes to Beis Moshiach 744 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409. Copyright 2007 by Beis Moshiach, Inc. Beis Moshiach is not responsible for the content of the advertisements. A¤S>OJJ>I@ERP [Continued from last issue] In light of the above, the words of the Radak – that the Chariot of Yechezkel was revealed at the Giving WHY THE of the Torah – also require explanation. -

Rambamvrncwo K a O H R E H G D W H

RambamvrncWo hWd gherho ak T HE 13 P RINCIPLES OF F AITH T HE SLAGER EDITION RambamvrncWo hWd gherho ak T HE 13 P RINCIPLES OF F AITH P RINCIPLES VI & VII With an anthology of commentaries from the Talmud, Midrash, Rishonim and Acharonim, and elucidation from the works of the Lubavitcher Rebbe. Compiled and Adapted by Rabbi Chaim Miller The Gutnick Library of Jewish Classics Rambam - The 13 Principles of Faith Principles 6 & 7: Prophecy with commentary from classic Rabbinic texts, and the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson. ISBN-13: 978-1-934152-23-2 ISBN-10: 1-934152-23-4 © Copyright 2009 by Chaim Miller Published and Distributed by: Kol Menachem 827 Montgomery Street, Brooklyn NY 11213 1-888-580-1900 1-718-951-6328 1-718-953-3346 (Fax) www.kolmenachem.com [email protected] First Edition — June 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the copyright holder, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper or broadcast. Kol Menachem is a not-for-profit organization. Proceeds from the sales of books are allocated to future projects. Dedication of the thirteen principles of faith Rambam’s Thirteen Principles of Faith is dedicated to our dear friends D A V I D & L A R A S L A G E R N EW Y ORK / LONDON May the merit of spreading words of Torah illuminated by the teachings of Chasidus to thousands across the globe be a source of blessing for them and their family for generations to come.