Mia Anderssén-Löf He Speedily Comemia | May – a Comparative Study on Hardal and Haredi | 2017 Understandings of Exile and Redemption

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Seders Will Open Hearts

ב“ה :THIS WEEK’S TOPIC ערב פסח, י׳׳ד ניסן, תש״פ ISSUE The Rebbe’s meetings with 378 Erev Pesach, April 8, 2020 the chief rabbis of Israel For more on the topic, visit 70years.com HERE’S my STORY OPEN SEDERS WILL Generously OPEN HEARTS sponsored by the RABBI YAAKOV SHAPIRA they spoke about activities of the Israeli Rabbinate and the state of Yiddishkeit in Israel; and they discussed the prophecies concerning the coming of the Mashiach and the Final Redemption. They went from topic to topic, without pause, and their conversations were recorded, transcribed and later published. During the first visit in 1983, the Rebbe asked the chief rabbis how they felt being outside of Israel. My father said that he had never left the Holy Land before, and that the time away was very difficult for him. To bring him comfort, the Rebbe expounded on the Torah verse, “Jacob lifted his feet and went to the land of the people of the East,” pointing out that while Jacob’s departure from the Land of Israel was a spiritual descent, y father, Rabbi Avraham Shapira, served as the later it turned out that this descent was for the sake of a MAshkenazi chief rabbi of Israel from 1983 until 1993, greater ascent. All Jacob’s sons — who would give rise to while Rabbi Mordechai Eliyahu served as the Sephardic the Twelve Tribes of Israel — were born outside the Land. chief rabbi. During their tenure they traveled to the United This is why the great 11th century Torah commentator, States three times for the purpose of visiting the central Rashi, reads the phrase “lifted his feet” as meaning Jacob Jewish communities in America and getting to know their “moved with ease” because G-d had promised to protect leaders. -

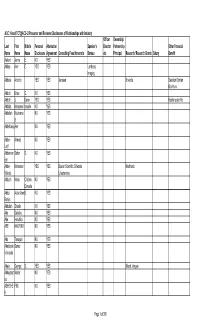

ACC14 and Tctacci2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures B.Pdf

ACC.14 and TCT@ACC-i2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures of Relationships with Industry Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Aaland Jenna E. NO YES Abbas Amr E. YES YES Lantheus Imaging Abbate Antonio YES YES Janssen Novartis Swedish Orphan Biovitrum Abbott Brian G. NO YES Abbott J. Dawn YES YES Boston scientific Abdalla Mohamed Ismaile NO YES Abdallah Mouhama NO YES d Abdelbaky Amr NO YES Abdel- Ahmed NO YES Latif Abdelmon Sahar S. NO YES eim Abdel- Mohamed YES YES Boston Scientific, Edwards Medtronic Wahab Lifesciences Abduch Maria Cristina NO YES Donadio Abdul Aizai Azan B. NO YES Rahim Abdullah Shuaib NO YES Abe Daisuke NO YES Abe Haruhiko NO YES ABE NAOYUKI NO YES Abe Takayuki NO YES Abedzade Sanaz NO YES h Anaraki Abela George S. YES YES Merck, Amgen Abhayarat Walter NO YES na ABHISHE FNU NO YES K Page 1 of 350 Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Abidi Syed NO YES Abidov Aiden NO YES Abi-samra Freddy Michel NO YES Abizaid Alexandre YES YES Abbott, Boston Scientific Abo- Elsayed NO YES Salem Abou- Alex NO YES Chebl AbouEzze Omar F NO YES ddine Aboulhosn Jamil A. YES YES GE Medical, Actelion United Therapeutics, Actelion Pharmaceuticals Pharmaceuticals Abraham Jacob NO YES Abraham JoEllyn Moore NO YES Abraham Maria Roselle NO YES Abraham Theodore P. -

400 Editor RABBI SHIMON HELINGER

ב"ה למען ישמעו • פרשת תצוה • 400 EDITOR RABBI SHIMON HELINGER PURIM A POTENT DAY INTENSE REJOICING The Rebbe once said: It’s obvious that we must distance ourselves entirely The Zohar notes that Purim is similar to Yom We read in the Gemara that on Purim one must drink from anything negative (“cursed be Haman”), HaKipurim. This means that what is accomplished “until he cannot differentiate (“ad d’lo yada”) between and seek to treasure and embrace all good things on Yom Kippur by fasting can be accomplished ‘cursed be Haman’ and ‘blessed be Mordechai.’ ” (“blessed be Mordechai”). That applies at any time. on Purim by rejoicing. Furthermore, the very The Gemara relates a story of two amoraim, Rabbah The unique aspect of Purim is that we can accomplish name Kipurim (“like Purim”), implies that Purim and Rav Zeira, who had their Purim seuda together, this by allowing our neshama to express itself freely. is the greater Yom-Tov, impacting a person sharing profound secrets of the Torah over a This kind of avoda is superior to serving HaShem by more powerfully. number of cups of wine. However, Rav Zeira was so means of conscious thought (yada). Indeed, in this Indeed, Chazal teach that when Moshiach comes, all overwhelmed by the intense kedusha of Rabbah’s kind of avoda we can resemble the Yidden at the the Yomim-Tovim will cease to exist; only the Yom- revelations that his neshama left his body. time of the Purim story who, when the inner power Tov of Purim will remain. Chassidus explains that of their neshamos surfaced, fulfilled all the mitzvos the joy and holiness of Purim are so great, that even faithfully, even to the point of mesiras nefesh. -

ONEIROCRITICS and MIDRASH on Reading Dreams and the Scripture

ONEIROCRITICS AND MIDRASH On Reading Dreams and the Scripture Erik Alvstad A bstr act In the context of ancient theories of dreams and their interpretation, the rabbinic literature offers particularly interesting loci. Even though the view on the nature of dreams is far from un- ambiguous, the rabbinic tradition of oneirocritics, i.e. the discourse on how dreams are interpreted, stands out as highly original. As has been shown in earlier research, oneirocritics resembles scriptural interpretation, midrash, to which it has lent some of its exegetical rules. This article will primarily investigate the interpreter’s role in the rabbinic practice of dream interpretation, as reflected in a few rabbinic stories from the two Talmuds and from midrashim. It is shown that these narrative examples have some common themes. They all illustrate the polysemy of the dream-text, and how the person who puts an interpretation on it constructs the dream’s significance. Most of the stories also emphasize that the outcome of the dream is postponed until triggered by its interpretation. Thus the dreams are, in a sense, pictured as prophetic – but it is rather the interpreter that constitutes the prophetic instance, not the dream itself. This analysis is followed by a concluding discussion on the analogical relation between the Scripture and the dream-text, and the interpretative practices of midrash and oneirocritics. he striking similarities between the rabbinic traditions of Scriptural exegesis, midrash, and the rabbinic practice of Tdream interpretation, -

Israel's National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict

Leap of Faith: Israel’s National Religious and the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict Middle East Report N°147 | 21 November 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iv I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Religious Zionism: From Ascendance to Fragmentation ................................................ 5 A. 1973: A Turning Point ................................................................................................ 5 B. 1980s and 1990s: Polarisation ................................................................................... 7 C. The Gaza Disengagement and its Aftermath ............................................................. 11 III. Settling the Land .............................................................................................................. 14 A. Bargaining with the State: The Kookists ................................................................... 15 B. Defying the State: The Hilltop Youth ........................................................................ 17 IV. From the Hills to the State .............................................................................................. -

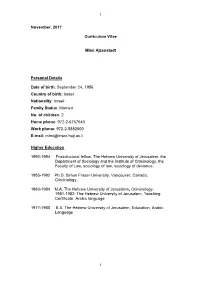

CV July 2017

1 November, 2017 Curriculum Vitae Mimi Ajzenstadt Personal Details Date of birth: September 24, 1956 Country of birth: Israel Nationality: Israeli Family Status: Married No. of children: 2 Home phone: 972-2-6767540 Work phone: 972-2-5882600 E-mail: [email protected] Higher Education 1992-1994 Post-doctoral fellow, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Department of Sociology and the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law, sociology of law, sociology of deviance. 1985-1992 Ph.D. Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada, Criminology. 1980-1984 M.A. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Criminology. 1981-1982: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Teaching Certificate, Arabic language 1977-1980 B.A. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Education, Arabic Language 1 2 Appointments at the Hebrew University 2012- present Full Professor, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 2007– 2012 Associate Professor, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 2002- 2007 Senior Lecturer, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work and Social Welfare. 1994-2002 Lecturer, the Institute of Criminology, the Faculty of Law and the Paul Baerwald School of Social Work. Service in other Academic Institutions Summer, 2011 Visiting Professor, Cambridge University. Summer, 2010 Visiting Professor. University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada. 2005 -2006 Visiting Professor. University of Maryland, Maryland, USA. Winter, 2000 Visiting Scholar. Stockholm University, Sweden. Fall 1999 Visiting Scholar. Yale University, New-Haven, Connecticut, U.S.A., Law School. -

Have You Heard of These Ethnic Groups?

Have you heard of these Ethnic Groups? Ethnic Group Homeland Population Bhils India 17.1 million Kazahs Kazakhstan 18 million Tagalogs Philippines 19.6 million Amhara Ethiopia 19.9 million Berbers Algeria, Morocco, 20-50 million Tunisia, Libya Fula West Africa 20-25 million Igbo Nigeria 20 million Khas Nepal 20 million Yoruba Nigeria 20 million Akan Ghana 20.9 million Source: https://joshuaproject.net/unreached/11 Have you heard of these Ethnic Groups? Ethnic Group Homeland Population Bhils India 17.1 million Kazahs Kazakhstan 18 million Tagalogs Philippines 19.6 million Amhara Ethiopia 19.9 million Berbers Algeria, Morocco, 20-50 million Tunisia, Libya Fula West Africa 20-25 million Igbo Nigeria 20 million Khas Nepal 20 million Yoruba Nigeria 20 million Akan Ghana 20.9 million Jews Israel (worldwide) 14.7 million (2019) Sources: https://joshuaproject.net/unreached/1 2 Berman Jewish Databank: https://www.jewishdatabank.org/databank/search-results?category=Global Facts about the Jewish People • Nobel Prize winners (1901-2018): 900 total. 208 were Jewish (Israel has produced a disproportionate number of Nobel Prize winners)https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jewis h-nobel-prize-laureates • 8 US Supreme Court Justices: Louis Brandeis (1916-1939), Benjamin Carodozo (1931-9138), Felix Frankfurter (1939-1962), Arthur Goldberg (1962-1965), Abe Fortas (1965-1969), Ruth Ginsburg (1993-2020), Stephen Breyer (1994-), Elena Kagan (2010-) https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jewish-u-s- supreme-court-justices 3 Facts about the Jewish People • Jews -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

The Soul of a Jew and the Soul of a Non-Jew an Inconvenient Truth and the Search for an Alternative

47 The Soul of a Jew and the Soul of a Non-Jew An Inconvenient Truth and the Search for an Alternative By: HANAN BALK Holiness is not found in the human being in essence unless he sanctifies himself. According to his preparation for holiness, so the fullness comes upon him from on High. A person does not acquire holiness while inside his mother. He is not holy from the womb, but has to labor from the very day he comes into the air of the world. 1 Introduction: The Soul of a Jew is Superior to that of a Non-Jew The view expressed in the above heading—as uncomfortable and racially charged as it may be in the minds of some—was undoubtedly, as we shall show, the prominent position maintained by authorities of Jewish thought throughout the ages, and continues to be so even today. While Jewish mysticism is the source and primary expositor of this theory, it has achieved a ubiquitous presence not only in the writings of Kabbalists,2 but also in the works of thinkers found in the libraries of most observant Jews, who hardly consider themselves followers of Kabbalah. Clearly, for one committed to the Torah and its principles, it is not tenable to presume that so long as he is not a Kabbalist, such a belief need not be a part of his religious worldview. Is there an alternative view that is an equally authentic representation of Jewish thought on the subject? In response to this question, we will 1 R. Simhạ Bunim of Przysukha, Kol Simha,̣ Parshat Miketz, p. -

Jewish Subcultures Online: Outreach, Dating, and Marginalized Communities ______

JEWISH SUBCULTURES ONLINE: OUTREACH, DATING, AND MARGINALIZED COMMUNITIES ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in American Studies ____________________________________ By Rachel Sara Schiff Thesis Committee Approval: Professor Leila Zenderland, Chair Professor Terri Snyder, Department of American Studies Professor Carrie Lane, Department of American Studies Spring, 2016 ABSTRACT This thesis explores how Jewish individuals use and create communities online to enrich their Jewish identity. The Internet provides Jews who do not fit within their brick and mortar communities an outlet that gives them voice, power, and sometimes anonymity. They use these websites to balance their Jewish identities and other personal identities that may or may not fit within their local Jewish community. This research was conducted through analyzing a broad range of websites. The first chapter, the introduction, describes the Jewish American population as a whole as well as the history of the Internet. The second chapter, entitled “The Black Hats of the Internet,” discusses how the Orthodox community has used the Internet to create a modern approach to outreach. It focuses in particular on the extensive web materials created by Chabad and Aish Hatorah, which offer surprisingly modern twists on traditional texts. The third chapter is about Jewish online dating. It uses JDate and other secular websites to analyze how Jewish singles are using the Internet. This chapter also suggests that the use of the Internet may have an impact on reducing interfaith marriage. The fourth chapter examines marginalized communities, focusing on the following: Jewrotica; the Jewish LGBT community including those who are “OLGBT” (Orthodox LGBT); Punk Jews; and feminist Jews. -

T E M P L E B E T H a B R a H

the Volume 31, Number 7 March 2012 TEMPLE BETH ABRAHAM Adar / Nisan 5772 Volume 37, Number 10 June 2018, Sivan-Tammuz 5778 Sunset over Ocean Beach. Photo by Milah Gammon. R i Pu M WHAT’S HAPPENING SERVICES SCHEDULE MAH JONGG Monday & Thursday Morning Minyan Join a game on the 2nd In the Chapel, 8:00 a.m. On Holidays, start time is 9:00 a.m. Shabbat of each month as we gather in the Chapel after Friday Evening (Kabbalat Shabbat) Kiddush. In the Chapel, 6:15 p.m. June 9; July 14; August 11 Candle Lighting (Friday) 6/1 8:03pm 7/6 8:16pm 8/3 7:57pm This summer come to 6/8 8:07pm 7/13 8:13pm 8/10 7:49pm Limmud 6/15 8:11pm 7/20 8:09pm 8/17 7:41pm 6/22 8:12pm 7/27 8:04pm 8/24 7:31pm Bay Area 6/29 8:13pm 8/31 7:21pm Festival 2018 Shabbat Morning In the Sanctuary, 9:30 a.m. and spend a long weekend (6/29-7/1) in a Jewish enriching and immersive camp for families of all ages Torah Portions (Saturday) and religious movements! Check it out at limmud- June 2 Beha’alotcha bayarea.org, or contact Oded & Dara Pincas (TBA June 9 Sh’lach members) at [email protected] for more details. June 16 Korach Take advantage of a group discount. June 23 Chukat Promotional code: TBA. Additional discounts are available for a full Camp and Teen June 30 Balak programs - request at [email protected]. -

Israel's Chief Rabbis

Israel’s Chief Rabbis: Rabbi Avraham Elkanah Kahana Shapira R’ Mordechai Torczyner – [email protected] 1. Rabbi Avraham Shapira, 1914-2007; Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi 1984-1993 2. Rabbi Yitzchak Steinberg, Eulogy at https://www.yutorah.org/lectures/lecture.cfm/775436/, 20-22 min. Rav Shapira was the oz haTorah. His might, and the strength he had, through the Torah he learned… In Rav Shapira we felt his strength in Torah was so powerful, so strong, that he wasn’t afraid of anything. His psak halachah was clear he wasn’t afraid of people around him, of those who were usually more appreciative of – לא תגורו מפני איש .and cut him, of his circles and so on, and he wasn’t afraid of anyone from the outer circles, from those, from politicians and those who control the country. Yet he wasn’t afraid of them at all… Biography 3. http://www.mercazharav.org.il/?pg=17 In one of his first days in Yeshivat Chevron, during a lecture by the great Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Epstein zt”l to the entire student body, he asked a great question against the entire flow of the lecture. Rabbi Epstein halted the lecture for a few seconds, thought about it, and then continued the lecture as if nothing had been asked. At the start of the next general lecture, Rabbi Epstein asked, “Where is the little one (our master was both young and short in those days) who asked the question in the previous lecture?” After he found him, he continued with a lecture which revolved around the question he had asked in the previous lecture.