A Dynamic Semantics of Single-Wh and Multiple-Wh Questions*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radical Inquisitive Semantics∗

Radical inquisitive semantics∗ Jeroen Groenendijk and Floris Roelofsen ILLC/Department of Philosophy University of Amsterdam http://www.illc.uva.nl/inquisitive-semantics October 6, 2010 Contents 1 Inquisitive semantics: propositions as proposals 2 1.1 Logic and conversation . .3 1.2 Compliance . .4 1.3 Counter-compliance . .5 2 Radical inquisitive semantics 6 2.1 Atoms, disjunction, and conjunction . .8 2.2 Negation . 12 2.3 Questions . 15 2.4 Implication . 18 3 Refusal, supposition and the Ramsey test 23 3.1 Refusing a proposal . 24 3.2 Suppositions . 26 ∗This an abridged version of a paper in the making. Earlier versions were presented in a seminar at the University of Massachusetts Amherst on April 12 and 21, 2010, at the Journ´ees S´emantiqueet Mod´elisation in Nancy (March 25, 2010), at the Formal Theories of Communication workshop at the Lorentz Center in Leiden (February 26, 2010), and at colloquia at the ILLC in Amsterdam (February 5, 2010) and the ICS in Osnabruck¨ (January 13, 2010). 1 3.3 Conditional questions . 27 3.4 The Ramsey test . 28 3.5 Conditional questions and questioned conditionals . 30 4 Minimal change semantics for conditionals 32 4.1 Unconditionals . 33 4.2 Dependency . 34 4.3 Minimal change with disjunctive antecedents . 36 4.4 Alternatives without disjunction . 39 4.5 Strengthening versus simplification . 40 5 Types of proposals 41 5.1 Suppositionality, informativeness, and inquisitiveness . 41 5.2 Questions, assertions, and hybrids . 42 6 Assessing a proposal 42 6.1 Licity, acceptability, and objectionability . 42 6.2 Support and unobjectionability . 44 6.3 Resolvability and counter-resolvability . -

Vagueness: Insights from Martin, Jeroen, and Frank

Vagueness: insights from Martin, Jeroen, and Frank Robert van Rooij 1 Introduction My views on the semantic and pragmatic interpretation of natural language were in- fluenced a lot by the works of Martin, Jeroen and Frank. What attracted me most is that although their work is always linguistically relevant, it still has a philosophical point to make. As a student (not in Amsterdam), I was already inspired a lot by their work on dynamics semantics, and by Veltman’s work on data semantics. Afterwards, the earlier work on the interpretation of questions and aswers by Martin and Jeroen played a signifcant role in many of my papers. Moreover, during the years in Amster- dam I developped—like almost anyone else who ever teached logic and/or philosophy of language to philosophy students at the UvA—a love-hate relation with the work of Wittgenstein, for which I take Martin to be responsible, at least to a large extent. In recent years, I worked a lot on vagueness, and originally I was again influenced by the work of one of the three; this time the (unpublished) notes on vagueness by Frank. But in recent joint work with Pablo Cobreros, Paul Egr´eand Dave Ripley, we developed an analysis of vagueness and transparant truth far away from anything ever published by Martin, Jeroen, or Frank. But only recently I realized that I have gone too far: I should have taken more seriously some insights due to Martin, Jeroen and/or Frank also for the analysis of vagueness and transparant truth. I should have listened more carefully to the wise words of Martin always to take • Wittgenstein seriously. -

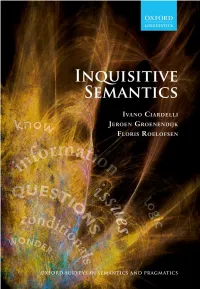

Inquisitive Semantics OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, //, Spi

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, //, SPi Inquisitive Semantics OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, //, SPi OXFORD SURVEYS IN SEMANTICS AND PRAGMATICS general editors: Chris Barker, NewYorkUniversity, and Christopher Kennedy, University of Chicago advisory editors: Kent Bach, San Francisco State University; Jack Hoeksema, University of Groningen;LaurenceR.Horn,Yale University; William Ladusaw, University of California Santa Cruz; Richard Larson, Stony Brook University; Beth Levin, Stanford University;MarkSteedman,University of Edinburgh; Anna Szabolcsi, New York University; Gregory Ward, Northwestern University published Modality Paul Portner Reference Barbara Abbott Intonation and Meaning Daniel Büring Questions Veneeta Dayal Mood Paul Portner Inquisitive Semantics Ivano Ciardelli, Jeroen Groenendijk, and Floris Roelofsen in preparation Aspect Hana Filip Lexical Pragmatics Laurence R. Horn Conversational Implicature Yan Huang OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, //, SPi Inquisitive Semantics IVANO CIARDELLI, JEROEN GROENENDIJK, AND FLORIS ROELOFSEN 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, //, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox dp, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Ivano Ciardelli, Jeroen Groenendijk, and Floris Roelofsen The moral rights of the authors have been asserted First Edition published in Impression: Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, for commercial purposes, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rights organization. This is an open access publication, available online and distributed under the terms ofa Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial – No Derivatives . -

Reasoning on Issues: One Logic and a Half

Reasoning on issues: one logic and a half Ivano Ciardelli partly based on joint work with Jeroen Groenendijk and Floris Roelofsen KNAW Colloquium on Dependence Logic — 3 March 2014 Overview 1. Dichotomous inquisitive logic: reasoning with issues 2. Inquisitive epistemic logic: reasoning about entertaining issues 3. Inquisitive dynamic epistemic logic: reasoning about raising issues Overview 1. Dichotomous inquisitive logic: reasoning with issues 2. Inquisitive epistemic logic: reasoning about entertaining issues 3. Inquisitive dynamic epistemic logic: reasoning about raising issues Preliminaries Information states I Let W be a set of possible worlds. I Definition: an information state is a set of possible worlds. I We identify a body of information with the worlds compatible with it. I t is at least as informed as s in case t ⊆ s. I The state ; compatible with no worlds is called the absurd state. w1 w2 w1 w2 w1 w2 w1 w2 w3 w4 w3 w4 w3 w4 w3 w4 (a) (b) (c) (d) Preliminaries Issues I Definition: an issue is a non-empty, downward closed set of states. I An issue is identified with the information needed to resolve it. S I An issue I is an issue over a state s in case s = I. I The alternatives for an issue I are the maximal elements of I. w1 w2 w1 w2 w1 w2 w1 w2 w3 w4 w3 w4 w3 w4 w3 w4 (e) (f) (g) (h) Four issues over fw1; w2; w3; w4g: only alternatives are displayed. Part I Dichotomous inquisitive logic: reasoning with issues Dichotomous inquisitive semantics Definition (Syntax of InqDπ) LInqDπ consists of a set L! of declaratives and a set L? of interrogatives: 1. -

A Guide to Dynamic Semantics

A Guide to Dynamic Semantics Paul Dekker ILLC/Department of Philosophy University of Amsterdam September 15, 2008 1 Introduction In this article we give an introduction to the idea and workings of dynamic se- mantics. We start with an overview of its historical background and motivation in this introductory section. An in-depth description of a paradigm version of dynamic semantics, Dynamic Predicate Logic, is given in section 2. In section 3 we discuss some applications of the dynamic kind of interpretation to illustrate how it can be taken to neatly account for a vast number of empirical phenom- ena. In section 4 more radical extensions of the basic paradigm are discussed, all of them systematically incorporating previously deemed pragmatic aspects of meaning in the interpretational system. Finally, a discussion of some more general, philosophical and theoretical, issues surrounding dynamic semantics can be found in section 5. 1.1 Theoretical Background What is dynamic semantics. Some people claim it embodies a radical new view of meaning, departing from the main logical paradigm as it has been prominent in most of the previous century. Meaning, or so it is said, is not some object, or some Platonic entity, but it is something that changes information states. A very simple-minded way of putting the idea is that people uses languages, they have cognitive states, and what language does is change these states. “Natu- ral languages are programming languages for minds”, it has been said. Others build on the assumption that natural language and its interpretation is not just concerned with describing an independently given world, but that there are lots of others things relevant in the interpretation of discourse, and lots of other functions of language than a merely descriptive one. -

Chapter 3 Describing Syntax and Semantics

Chapter 3 Describing Syntax and Semantics 3.1 Introduction 110 3.2 The General Problem of Describing Syntax 111 3.3 Formal Methods of Describing Syntax 113 3.4 Attribute Grammars 128 3.5 Describing the Meanings of Programs: Dynamic Semantics 134 Summary • Bibliographic Notes • Review Questions • Problem Set 155 CMPS401 Class Notes (Chap03) Page 1 / 25 Dr. Kuo-pao Yang Chapter 3 Describing Syntax and Semantics 3.1 Introduction 110 Syntax – the form of the expressions, statements, and program units Semantics - the meaning of the expressions, statements, and program units. Ex: the syntax of a Java while statement is while (boolean_expr) statement – The semantics of this statement form is that when the current value of the Boolean expression is true, the embedded statement is executed. – The form of a statement should strongly suggest what the statement is meant to accomplish. 3.2 The General Problem of Describing Syntax 111 A sentence or “statement” is a string of characters over some alphabet. The syntax rules of a language specify which strings of characters from the language’s alphabet are in the language. A language is a set of sentences. A lexeme is the lowest level syntactic unit of a language. It includes identifiers, literals, operators, and special word (e.g. *, sum, begin). A program is strings of lexemes. A token is a category of lexemes (e.g., identifier). An identifier is a token that have lexemes, or instances, such as sum and total. Ex: index = 2 * count + 17; Lexemes Tokens index identifier = equal_sign 2 int_literal * mult_op count identifier + plus_op 17 int_literal ; semicolon CMPS401 Class Notes (Chap03) Page 2 / 25 Dr. -

Negation, Alternatives, and Negative Polar Questions in American English

Negation, alternatives, and negative polar questions in American English Scott AnderBois Scott [email protected] February 7, 2016 Abstract A longstanding puzzle in the semantics/pragmatics of questions has been the sub- tle differences between positive (e.g. Is it . ?), low negative (Is it not . ?), and high negative polar questions (Isn't it . ?). While they are intuitively ways of ask- ing \the same question", each has distinct felicity conditions and gives rise to different inferences about the speaker's attitude towards this issue and expectations about the state of the discourse. In contrast to their non-interchangeability, the vacuity of double negation means that most theories predict all three to be semantically identical. In this chapter, we build on the non-vacuity of double negation found in inquisitive seman- tics (e.g. Groenendijk & Roelofsen (2009), AnderBois (2012), Ciardelli et al. (2013)) to break this symmetry. Specifically, we propose a finer-grained version of inquisitive semantics { what we dub `two-tiered' inquisitive semantics { which distinguishes the `main' yes/no issue from secondary `projected' issues. While the main issue is the same across positive and negative counterparts, we propose an account deriving their distinc- tive properties from these projected issues together with pragmatic reasoning about the speaker's choice of projected issue. Keywords: Bias, Negation, Polar Questions, Potential QUDs, Verum Focus 1 Introduction When a speaker wants to ask a polar question in English, they face a choice between a bevy of different possible forms. While some of these differ dramatically in form (e.g. rising declaratives, tag questions), even focusing more narrowly on those which only have interrogative syntax, we find a variety of different forms, as in (1). -

Free Choice and Homogeneity

Semantics & Pragmatics Volume 12, Article 23, 2019 https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.12.23 This is an early access version of Goldstein, Simon. 2019. Free choice and homogeneity. Semantics and Prag- matics 12(23). 1–47. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.12.23. This version will be replaced with the final typeset version in due course. Note that page numbers will change, so cite with caution. ©2019 Simon Goldstein This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/). early access Free choice and homogeneity* Simon Goldstein Australian Catholic University Abstract This paper develops a semantic solution to the puzzle of Free Choice permission. The paper begins with a battery of impossibility results showing that Free Choice is in tension with a variety of classical principles, including Disjunction Introduction and the Law of Excluded Middle. Most interestingly, Free Choice appears incompatible with a principle concerning the behavior of Free Choice under negation, Double Prohibition, which says that Mary can’t have soup or salad implies Mary can’t have soup and Mary can’t have salad. Alonso-Ovalle 2006 and others have appealed to Double Prohibition to motivate pragmatic accounts of Free Choice. Aher 2012, Aloni 2018, and others have developed semantic accounts of Free Choice that also explain Double Prohibition. This paper offers a new semantic analysis of Free Choice designed to handle the full range of impossibility results involved in Free Choice. The paper develops the hypothesis that Free Choice is a homogeneity effect. -

Epistemic Implicatures and Inquisitive Bias: a Multidimensional Semantics for Polar Questions

EPISTEMIC IMPLICATURES AND INQUISITIVE BIAS: A MULTIDIMENSIONAL SEMANTICS FOR POLAR QUESTIONS by Morgan Mameni B.A., Simon Fraser University, 2008 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS c Morgan Mameni 2010 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2010 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for Fair Dealing. Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review, and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. APPROVAL Name: Morgan Mameni Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: Epistemic Implicatures and Inquisitive Bias: A Multidimensional Semantics for Polar Questions Examining Committee: Dr. John Alderete (Chair) Dr. Nancy Hedberg (Senior Supervisor) Associate Professor of Linguistics, SFU Dr. Chung-Hye Han (Supervisor) Associate Professor of Linguistics, SFU Dr. Francis Jeffry Pelletier (Supervisor) Professor of Linguistics and Philosophy, SFU Dr. Hotze Rullmann (Supervisor) Associate Professor of Linguistics, UBC Dr. Philip P. Hanson (External Examiner) Associate Professor of Philosophy, SFU Date Approved: July 2, 2010 ii Abstract This thesis motivates and develops a semantic distinction between two types of polar in- terrogatives available to natural languages, based on data from Persian and English. The first type, which I call an ‘impartial interrogative,’ has as its pragmatic source an ignorant information state, relative to an issue at a particular stage of the discourse. The second type, which I call a ‘partial interrogative’ arises from a destabilized information state, whereby the proposition supported by the information state conflicts with contextually available data. -

Chapter 3 – Describing Syntax and Semantics CS-4337 Organization of Programming Languages

!" # Chapter 3 – Describing Syntax and Semantics CS-4337 Organization of Programming Languages Dr. Chris Irwin Davis Email: [email protected] Phone: (972) 883-3574 Office: ECSS 4.705 Chapter 3 Topics • Introduction • The General Problem of Describing Syntax • Formal Methods of Describing Syntax • Attribute Grammars • Describing the Meanings of Programs: Dynamic Semantics 1-2 Introduction •Syntax: the form or structure of the expressions, statements, and program units •Semantics: the meaning of the expressions, statements, and program units •Syntax and semantics provide a language’s definition – Users of a language definition •Other language designers •Implementers •Programmers (the users of the language) 1-3 The General Problem of Describing Syntax: Terminology •A sentence is a string of characters over some alphabet •A language is a set of sentences •A lexeme is the lowest level syntactic unit of a language (e.g., *, sum, begin) •A token is a category of lexemes (e.g., identifier) 1-4 Example: Lexemes and Tokens index = 2 * count + 17 Lexemes Tokens index identifier = equal_sign 2 int_literal * mult_op count identifier + plus_op 17 int_literal ; semicolon Formal Definition of Languages • Recognizers – A recognition device reads input strings over the alphabet of the language and decides whether the input strings belong to the language – Example: syntax analysis part of a compiler - Detailed discussion of syntax analysis appears in Chapter 4 • Generators – A device that generates sentences of a language – One can determine if the syntax of a particular sentence is syntactically correct by comparing it to the structure of the generator 1-5 Formal Methods of Describing Syntax •Formal language-generation mechanisms, usually called grammars, are commonly used to describe the syntax of programming languages. -

Static Vs. Dynamic Semantics (1) Static Vs

Why Does PL Semantics Matter? (1) Why Does PL Semantics Matter? (2) • Documentation • Language Design - Programmers (“What does X mean? Did - Semantic simplicity is a good guiding G54FOP: Lecture 3 the compiler get it right?”) Programming Language Semantics: principle - Implementers (“How to implement X?”) Introduction - Ensure desirable meta-theoretical • Formal Reasoning properties hold (like “well-typed programs Henrik Nilsson - Proofs about programs do not go wrong”) University of Nottingham, UK - Proofs about programming languages • Education (E.g. “Well-typed programs do not go - Learning new languages wrong”) - Comparing languages - Proofs about tools (E.g. compiler correctness) • Research G54FOP: Lecture 3 – p.1/21 G54FOP: Lecture 3 – p.2/21 G54FOP: Lecture 3 – p.3/21 Static vs. Dynamic Semantics (1) Static vs. Dynamic Semantics (2) Styles of Semantics (1) Main examples: • Static Semantics: “compile-time” meaning Distinction between static and dynamic • Operational Semantics: Meaning given by semantics not always clear cut. E.g. - Scope rules Abstract Machine, often a Transition Function - Type rules • Multi-staged languages (“more than one mapping a state to a “more evaluated” state. Example: the meaning of 1+2 is an integer run-time”) Kinds: value (its type is Integer) • Dependently typed languages (computation - small-step semantics: each step is • Dynamic Semantics: “run-time” meaning at the type level) atomic; more machine like - Exactly what value does a term evaluate to? - structural operational semantics (SOS): - What are the effects of a computation? compound, but still simple, steps Example: the meaning of 1+2 is the integer 3. - big-step or natural semantics: Single, compound step evaluates term to final value. -

Three Notions of Dynamicness in Language∗

Three Notions of Dynamicness in Language∗ Daniel Rothschild† Seth Yalcin‡ [email protected] [email protected] June 7, 2016 Abstract We distinguish three ways that a theory of linguistic meaning and com- munication might be considered dynamic in character. We provide some examples of systems which are dynamic in some of these senses but not others. We suggest that separating these notions can help to clarify what is at issue in particular debates about dynamic versus static approaches within natural language semantics and pragmatics. In the seventies and early eighties, theorists like Karttunen, Stalnaker, Lewis, Kamp, and Heim began to `formalize pragmatics', in the process making the whole conversation or discourse itself the object of systematic formal investiga- tion (Karttunen[1969, 1974]; Stalnaker[1974, 1978]; Lewis[1979]; Kamp[1981]; Heim[1982]; see also Hamblin[1971], Gazdar[1979]). This development some- times gets called \the dynamic turn". Much of this work was motivated by a desire to model linguistic phenomena that seemed to involve a special sen- sitivity to the preceding discourse (with presupposition and anaphora looming especially large)|what we could loosely call dynamic phenomena. The work of Heim[1982] in particular showed the possibility of a theory of meaning which identified the meaning of a sentence with (not truth-conditions but) its potential to influence the state of the conversation. The advent of this kind of dynamic compositional semantics opened up a new question at the semantics-pragmatics interface: which seemingly dynamic phenomena are best handled within the compositional semantics (as in a dynamic semantics), and which are better modeled by appeal to a formal `dynamic pragmatics' understood as separable from, but perhaps interacting with, the compositional semantics? Versions of this question continue to be debated within core areas of semantic-pragmatic ∗The authors thank Jim Pryor and Lawerence Valby for essential conversations.