The Postmodern Writer and His Alter Ego: Julian Barnes Versus Dan Kavanagh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Title of the Thesis)*

TENDENCIA THATCHERITIS OR ENGLISHNESS REMADE The Fictions of Julian Barnes, Hanif Kureishi and Pat Barker by Heather Ann Joyce A thesis submitted to the Department of English In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen‘s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (July, 2011) Copyright © Heather Ann Joyce, 2011 Abstract Julian Barnes, Pat Barker, and Hanif Kureishi are all canonical authors whose fictions are widely believed to reflect the cultural and political state of a nation that is post-war, post-imperial and post-modern. While much has been written on how Barker‘s and Kureishi‘s early works in particular respond to and intervene in the presiding political narrative of the 1980s – Thatcherism – treatment of how revenants of Thatcherism have shaped these writers‘ works from 1990 on has remained cursory. Thatcherism is more than an obvious historical reference point for Barker, Barnes, and Kureishi; their works demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of how Thatcher‘s reworkings of the repertoires of Englishness – a representational as well as political and cultural endeavour – persist beyond her time in office. Barnes, Barker, and Kureishi seem to have reached the same conclusion as political and cultural critics: Thatcher and Thatcherism have remade not only the contemporary political and cultural landscapes but also the electorate and consequently the English themselves. Tony Blair‘s conception of the New Britain proved less than satisfactory because contemporary repertoires of Englishness repeat and rework historical and not incidentally imperial formulations of England and Englishness rather than envision civic and populist formulations of renewal. Barnes‘s England, England and Arthur & George confront the discourse of inevitability that has come to be attached to contemporary formulations of both political and cultural Englishness – both in terms of its predictable demise and its belated celebration. -

Fine Books in All Fields

Sale 480 Thursday, May 24, 2012 11:00 AM Fine Literature – Fine Books in All Fields Auction Preview Tuesday May 22, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wednesday, May 23, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Thursday, May 24, 9:00 am to 11:00 am Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www.pbagalleries. com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. CONSIGN TO PBA GALLERIES PBA is always happy to discuss consignments of books, maps, photographs, graphics, autographs and related material. -

Monthly Multidisciplinary Research Journal Review of Research Journal

Vol II Issue V Feb 2013 ISSN No : 2249-894X ORIGINAL ARTICLE Monthly Multidisciplinary Research Journal Review Of Research Journal Chief Editors Ashok Yakkaldevi Flávio de São Pedro Filho A R Burla College, India Federal University of Rondonia, Brazil Ecaterina Patrascu Kamani Perera Spiru Haret University, Bucharest Regional Centre For Strategic Studies, Sri Lanka Welcome to Review Of Research RNI MAHMUL/2011/38595 ISSN No.2249-894X Review Of Research Journal is a multidisciplinary research journal, published monthly in English, Hindi & Marathi Language. All research papers submitted to the journal will be double - blind peer reviewed referred by members of the editorial Board readers will include investigator in universities, research institutes government and industry with research interest in the general subjects. Advisory Board Flávio de São Pedro Filho Horia Patrascu Mabel Miao Federal University of Rondonia, Brazil Spiru Haret University, Bucharest, Romania Center for China and Globalization, China Kamani Perera Delia Serbescu Ruth Wolf Regional Centre For Strategic Studies, Sri Spiru Haret University, Bucharest, Romania University Walla, Israel Lanka Xiaohua Yang Jie Hao Ecaterina Patrascu University of San Francisco, San Francisco University of Sydney, Australia Spiru Haret University, Bucharest Karina Xavier Pei-Shan Kao Andrea Fabricio Moraes de AlmeidaFederal Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), University of Essex, United Kingdom University of Rondonia, Brazil USA Osmar Siena Catalina Neculai May Hongmei Gao Brazil University of Coventry, UK Kennesaw State University, USA Loredana Bosca Anna Maria Constantinovici Marc Fetscherin Spiru Haret University, Romania AL. I. Cuza University, Romania Rollins College, USA Romona Mihaila Liu Chen Ilie Pintea Spiru Haret University, Romania Beijing Foreign Studies University, China Spiru Haret University, Romania Mahdi Moharrampour Nimita Khanna Govind P. -

Stile Titolo 1

International Journal of English and Comparative Literary Studies Website: https://bcsdjournals.com/index.php/ijecls ISSN: 2709-4952(Print) 2709-7390(Online) Vol.2, Issue 2, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.47631/ijecls.v2i2.225 The Transformation of the ‘Flaneur’ Figure to Bourgeois in Julian Barnes’s Metroland: A Critical Analysis Suraiya Sultana Abstract Charles Baudelaire employs the notion of flaneur as an idle wanderer and a passionate observer of the city life in the context of nineteenth-century Paris. Walter Benjamin in the twentieth century revisits the same notion in a slightly different manner. For Benjamin, flaneur, on the one hand, can be overwhelmed by the phantasmagoria of the city life and can develop a ‘shock experience' and on the other hand, can respond to the stimuli of the urban ambiance and can exhibit instrumental means of thinking to cope with the altered environment. In this circumstance, the latter, as Benjamin argues, is also evocative of the prospect of the flaneur’s conversion into a commodity. Following the argument of Walter Benjamin, the present paper aims to analyze the mobility and transformation of the central character, Christopher, in Julian Barnes’s novel Metroland (1980). This paper also reinforces that the character’s transformation is influenced by the societal structures as propounded by the structural Marxists like Louis Althusser. Keywords Flaneur, Phantasmagoria , Ambience, Transformation, Commodity. IJECLS 41 Suraiya Sultana, The Transformation of the ‘Flaneur’ Figure to Bourgeois in Julian Barnes’s Metroland The Transformation of the ‘Flaneur’ Figure to Bourgeois in Julian Barnes’s Metroland: A Critical Analysis Suraiya Sultana According to the Oxford Learner’s Dictionary, the word transformation means a complete change of someone or something. -

Filosofická Fakulta Masarykovy Univerzity

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies Teaching English Language and Literature for Secondary Schools Bc. Radek Nikl The Concept of Memory in Selected Works by Julian Barnes Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Stephen Paul Hardy, Ph. D. 2015 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author‘s signature 2 Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor, Mr Stephen Paul Hardy, PhD. for his patient guidance and to Mr James Edward Thomas for advice in the area of corpora linguistics. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 5 1.1 Main Secondary Sources 6 2. Julian Barnes 8 2.1 Biography 8 2.2 Julian Barnes in Literary Criticism 9 2.3 Recurrent Themes 12 3. History in A History of the World in 10 ½ Chapters 17 3.1 Analysis 17 3.2 Chapter Summaries with Examples and Commentaries 18 4. Historiographic Fiction in Arthur & George 36 4.1 Plot Summary 36 4.2 Analysis 37 4.3 Examples with Commentaries 40 5. Memory in The Sense of an Ending 47 5.1 Plot Summary 47 5.2 Analysis 48 5.3 Examples with Commentaries 50 6. Lexical Field of Memory/History in Individual Works 63 7. Conclusion 72 8. Works Cited and Consulted 75 9. Résumé 77 4 1. Introduction For my master‘s thesis I have decided to research the concept of memory in three selected works by Julian Barnes. Memory has been a prominent motif in Barnes‘ novels, be it in the form of a satirical account of the history of the world, as was the case of A History of the World in 10 ½ Chapters, or through the personal histories of main protagonists, where biographical facts and fiction indiscernibly blend – as was the case of the novel Arthur & George. -

The Only Story Julian Barnes

BIBLIOTECA TECLA SALA June 18, 2020 The Only Story Julian Barnes “Much of the pleasure in The Only Story comes from the wit and verbal precision that Barnes allows his narrator. Barnes’s switch from voice to voice is at once understated and dazzling.” —The New York Review of Books “The prose master paints a lovely, elegiac portrait of a young man’s disruptive love affair . forgoing the easy literary clichés of May- December romance for something much sadder, deeper, and more resonant.” —Entertainment Weekly Contents: Introduction 1 “Beautiful. Profoundly enjoyable. Through his precise attention to Brief Author 2 the marvels of love and his perfect stylistic accompaniments to each Biography state—Barnes has once again shown himself capable of transforming Barnes on suburbia 3 the mundane and ephemeral into the lyrical and lasting.” An exquisite look 4-5 —Los Angeles Review of Books at love Notes 6 “A thought-provoking meditation on memory and the seemingly endless complexities of love. Barnes’ prose is quietly elegant and adroit. [The Only Story] has strong, memorably drawn characters and a keen sense of time and place.” —Richmond Times-Dispatch [https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/568058/the-only-story-by-julian-barnes/] Page 2 Brief Author Biography Booker Prize (Flaubert's outstanding contributions as a Parrot 1984, England, European narrator and essayist. England 1998, and Arthur & On 25 January 2017, the French George 2005). Barnes's other President appointed Julian Barnes awards include the Somerset to the rank of Officier in the Maugham Award Ordre National de la Légion (Metroland 1981), Geoffrey Faber d'Honneur. -

Julian Barnes (Vintage Canada, 272 Pages, $19.95)

A consummate man of letters Barnes's new book collects his work on other writers Through the Window: Seventeen Essays and a Short Story, by Julian Barnes (Vintage Canada, 272 pages, $19.95) Saturday, Dec. 15, 2012 "I have lived in books, for books, by and with books; in recent years, I have been fortunate enough to be able to live from books." So says acclaimed British writer Julian Barnes, opening the preface to Through the Window, a new collection of his newspaper and magazine essays (plus a book introduction and a short story) published between 1997 and 2012. "And it was through books," he continues, "that I first realized there were other worlds beyond my own; first imagined what it might be like to be another person; first encountered that deeply intimate bond made when a writer's voice gets inside a reader's head." Barnes, the novelist, has been inside our heads for years. He debuted in 1980 with Metroland, followed up in 1982 with Before She Met Me and had his critical breakthrough in 1984 with Flaubert's Parrot, shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Son of schoolteachers, Oxford-educated, initially a book reviewer, literary editor and TV critic, Barnes became an author in his mid30s and has 11 novels to his name; three got Booker nods (Flaubert's Parrot; England, England; Arthur & George) and his latest, 2011's The Sense of an Ending, won it. He has written under a pseudonym, too: Dan Kavanagh, the family name of his late wife and literary agent, Pat; his four crime novels in the 1980s featured a bisexual private eye named Duffy. -

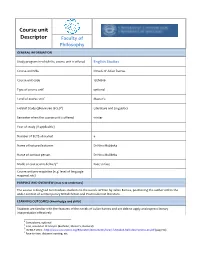

Course Unit Descriptor

Course unit Descriptor Faculty of Philosophy GENERAL INFORMATION Study program in which the course unit is offered English Studies Course unit title Novels of Julian Barnes Course unit code 15ЕМ019 Type of course unit1 optional Level of course unit2 Master’s Field of Study (please see ISCED3) Literature and Linguistics Semester when the course unit is offered winter Year of study (if applicable) Number of ECTS allocated 6 Name of lecturer/lecturers Dr Nina Muždeka Name of contact person Dr Nina Muždeka Mode of course unit delivery4 Face to face Course unit pre-requisites (e.g. level of language required, etc) PURPOSE AND OVERVIEW (max 5-10 sentences) The course is designed to introduce students to the novels written by Julian Barnes, positioning the author within the wider context of contemporary British fiction and Postmodernist literature. LEARNING OUTCOMES (knowledge and skills) Students are familiar with the features of the novels of Julian Barnes and are able to apply and express literary interpretation effectively. 1 Compulsory, optional 2 First, second or third cycle (Bachelor, Master's, Doctoral) 3 ISCED-F 2013 - http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Documents/isced-f-detailed-field-descriptions-en.pdf (page 54) 4 Face-to-face, distance learning, etc. SYLLABUS (outline and summary of topics) Lectures Historical and cultural background: contemporary British novel, Postmodernist literature. Metroland as a Bildungsroman. Before She Met Me: a psychological case study, art vs. reality. Talking It Over: A Postmodernist narrative experiment. Staring At the Sun: realism meets science fiction. England, England: identity construction. Porcupine as an example of engaged fiction. -

Flaubert's Parrot (1984), England, England (1998), and Arthur & George (2005) Had Been Previously Shortlisted for the Same Prize

Corso di Laurea magistrale in Lingue e Letterature Europee, Americane e Postcoloniali Tesi di Laurea A New Self, History, and Truth The Postmodern Quest in Julian Barnes’s Flaubert’s Parrot, A History of the World in 10 ½ Chapters, and Arthur & George Relatore Ch. Prof. Flavio Gregori Correlatore Ch. Prof. Shaul Bassi Laureanda Giulia Pavan Matricola 822433 Anno Accademico 2012 / 2013 1 To my mother and Francesca, for their patience 2 CONTENTS PART I 1. Introduction: Postmodernity as the age of Nihilism? 6 2. Postmodernism and Postmodernity 9 3. A new conception of Self 17 4. A new conception of History 23 5. A new conception of Truth 40 PART II 6. Julian Barnes: an overview 55 7. Parody of biography: reconstructing Flaubert through his parrot 60 7.1 Structure and themes 61 7.2 Flaubert and Barnes 65 7.3 Parroting academic biographies 76 8. Parody of historiography: reconstructing a history of the world in 10 ½ chapters 97 8.1. A polyphonic re-writing of history 102 8.2. The pattern of the novel and the pattern of history 127 8.3. Historiographic metafiction as parodic historiography 137 9. Parody of the trial: reconstructing a plurality of truths 147 9.1. History and biography writing as new forms of detection 152 9.2. Conclusion: a belief in objective truth as a way out of nihilism 165 BIBLIOGRAPHY 3 4 PART I 5 1. INTRODUCTION: POSTMODERNITY AS THE AGE OF NIHILISM? There are no facts, only interpretations. (Friedrich W. Nietzsche) Many scholars, belonging to the most disparate schools of thought, have felt that we are now standing at the end of the modern era. -

Reading Group Guide Spotlight

Spotlight on: Reading Group Guide Arthur & George Author: Julian Barnes Born January 9, 946, in Leicester, England; son of Name: Julian Barnes Albert Leonard (a French teacher) and Kaye (a French Born: January 9, 946 teacher) Barnes; married Pat Kavanagh (a literary Education: Magdalen agent), 979. Education: Magdalen College, Oxford, College, Oxford, B.A. B.A. (with honors), 968. Addresses: Agent: Peters, (with honors) Fraser, and Dunlop Ltd., Drury House, 34-43 Russell St., Address: Peters, Fraser, and London WC2B 5HA, England. Dunlop Ltd., Drury House, 34-43 Russell St., London WC2B 5HA, England. Career: Freelance writer, 972—. Lexicographer for Oxford English Dictionary Supplement, Oxford, England, 969-72; New Statesman, London, England, assistant literary editor, 977-78, television critic, 977-8; Sunday Times, London, deputy literary editor, 979-8; Observer, London, television critic, 982-86; London correspondent for New Yorker magazine, 990-94. Awards: Somerset Maugham Prize, 980, for Metroland; Booker Prize nomination, 984, Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize, and Prix Medicis, all for Flaubert’s Parrot; American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters award, 986, for work of distinction; Prix Gutembourg, 987; Premio Grinzane Carour, 988; Prix Femina for Talking It Over, 992; Shakespeare Prize (Hamburg), 993; Officier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres; shortlisted for Booker Prize, 998, for England, England. Writings: Novels Metroland, St. Martin’s Press (New York, NY), 980. Before She Met Me, Jonathan Cape (London, England), 982, McGraw-Hill (New York, NY), 986. Flaubert’s Parrot, Jonathan Cape (London, England), 984, Knopf (New York, NY), 985. Staring at the Sun, Jonathan Cape (London, England), 986, Knopf (New York, NY), 987. -

Julian Barnes

Julian Barnes: A Preliminary Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Barnes, Julian, 1946- Title: Julian Barnes Papers Dates: 1971-2000 Quantity: 19 boxes, 3 oversize boxes, 1 oversize folder (14.23 linear feet) Abstract: Papers include early typescript drafts, printer's copies, proofs, production material, and reviews of Barnes's works as well as his crime novels written under the pseudonym Dan Kavanagh. In addition, there are articles by and about Barnes, book reviews, fan mail, publisher's correspondence, letters from acquaintances and writers, publicity clippings, photographs, and posters. Access: Open for research, with the exception of restricted contracts and related correspondence Administrative Information Acquisition: Purchase, 2002 (Reg no. 14971) Processed by: Liz Murray, 2002 Repository: Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin Barnes, Julian, 1946- Scope and Contents The papers of British writer Julian Barnes span a thirty-year career from his first published fiction A Self-Possessed Woman (1975) to his recent novel, Love, etc. published in 2000. Represented in the collection are Barnes's novels Metroland (1980), Before She Met Me (1982), Flaubert's Parrot (1984), Staring at the Sun (1986), A History of the World in 10 1/2 Chapters (1989), Talking It Over (1991), The Porcupine (1992), Cross-Channel (1996), England, England (1998), and Love, etc. (2000). Also included are crime novels Barnes wrote under the pseudonym Dan Kavanagh, Going to the Dogs (1987), Duffy (1980), Fiddle City (1981), and Putting the Boot In (1985). Articles by and about Barnes, journalism, correspondence, clippings, photographs, and posters are also present. -

Overseas 2014

overSEAS 2014 This thesis was submitted by its author to the School of Eng- lish and American Studies, Eötvös Loránd University, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. It was found to be among the best theses submitted in 2014, therefore it was decorated with the School’s Outstanding Thesis Award. As such it is published in the form it was submitted in overSEAS 2014 (http://seas3.elte.hu/overseas/2014.html) DIPLOMAMUNKA MA THESIS Vecsernyés Dóra Anglisztika MA angol irodalom szakirány 2014 Certificate of Research By my signature below, I certify that my ELTE MA thesis, entitled “We’re a narrative animal, aren’t we?”: Remembrance in the Fiction of Julian Barnes is entirely the result of my own work, and that no degree has previously been conferred upon me for this work. In my thesis I have cited all the sources (printed, electronic or oral) I have used faithfully and have always indicated their origin. The electronic version of my thesis (in PDF format) is a true representation (identical copy) of this printed version. If this pledge is found to be false, I realize that I will be subject to penalties up to and including the forfeiture of the degree earned by my thesis. Date: 15th April 2014 Signed: ........................................ EÖTVÖS LORÁND TUDOMÁNYEGYETEM Bölcsészettudományi Kar DIPLOMAMUNKA MA THESIS Homo narrans: Az emlékezés mechanizmusai Julian Barnes regényeiben “We’re a narrative animal, aren’t we?”: Remembrance in the Fiction of Julian Barnes Témavezető: Készítette: Dr. Friedrich Judit, CSc Vecsernyés Dóra egyetemi docens Anglisztika MA angol irodalom szakirány 2014 Abstract The oeuvre of the contemporary English novelist and leading figure of postmodernism, Julian Barnes (1946- ) is known for having been in a prolific interaction with postmodernist concerns such as the inaccessibility of the past, the imperfection of memory, and the subjectivity of history writing.