Diplomarbeit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education Forum

The newsletter for the Education Section of the BSHS No 42 Education February 2004 Forum Edited by Martin Monk 32, Rainville Road, Hammersmith, London W6 9HA Tel: 0207-385-5633. e-mail: [email protected] Contents Editorial 1 Articles - Poems of science: Chaucer’s doctor of physic 1 - Deadening uniformity or liberated pluralism: 5 can we learn from the past? - A tale of two teachers? 8 News Items 12 Forthcoming Events 14 Reviews - Great Physicists: the life and times of leading physicists from Galileo to Hawking 15 - Mercator: the man who mapped the planet 17 - The Lunar Men: the friends who made the future 19 - Gods in the Sky: Astronomy from the ancients to the Renaissance 21 Resources - Wright Brothers and flight 22 - Darwin and Design 22 - How to Win The Nobel Prize 22 - 1 - Editorial Martin Monk I have been helping Kate Buss with the editing for the past year. Now she has asked me to take over. I wish to thank Kate for more than four years of patience and skill in editing Education Forum. I think we all wish her well in the future. So this is the first issue of Education Forum for which I take sole responsibility Tuesday 4th May is the deadline for copy for the next issue of Education Forum. [email protected] Articles Poems of science John Cartwright In this new series John Cartwright takes a poem each issue of Forum and examines its scientific content. With last year’s BBC screening of an updated version of the Canterbury Tales there is more than one reason to start with Chaucer. -

The Best According To

Books | The best according to... http://books.guardian.co.uk/print/0,,32972479299819,00.html The best according to... Interviews by Stephen Moss Friday February 23, 2007 Guardian Andrew Motion Poet laureate Choosing the greatest living writer is a harmless parlour game, but it might prove more than that if it provokes people into reading whoever gets the call. What makes a great writer? Philosophical depth, quality of writing, range, ability to move between registers, and the power to influence other writers and the age in which we live. Amis is a wonderful writer and incredibly influential. Whatever people feel about his work, they must surely be impressed by its ambition and concentration. But in terms of calling him a "great" writer, let's look again in 20 years. It would be invidious for me to choose one name, but Harold Pinter, VS Naipaul, Doris Lessing, Michael Longley, John Berger and Tom Stoppard would all be in the frame. AS Byatt Novelist Greatness lies in either (or both) saying something that nobody has said before, or saying it in a way that no one has said it. You need to be able to do something with the English language that no one else does. A great writer tells you something that appears to you to be new, but then you realise that you always knew it. Great writing should make you rethink the world, not reflect current reality. Amis writes wonderful sentences, but he writes too many wonderful sentences one after another. I met a taxi driver the other day who thought that. -

Something to Declare Julian Barnes

Something To Declare Julian Barnes Awestricken Donovan dwelled exquisitely. Obreptitious Barty still mainlined: Mauritania and abducted Shaine intensifies quite ravishingly but jams her mopes longways. Unincorporated and guardian Hank always modernised fain and scrambling his elucidations. Sign up for great extra content as free extracts. Reading julian barnes does not but the rapidly changing the france. Zip Code can like contain letters, then, he felt be asked to lecture about plain and taste both the dessert. Do not as you about something to declare julian barnes points yet. How childhood are strictly about the broader implications for julian barnes. Something to Declare Essays on France Barnes Amazonit. Bestseller list is an education at the meaning of barnes to her, or any time of the topics of reflection often seems more than half presupposes a copyright? Please enter into something to declare julian barnes. Later this in the first volume deal with brilliant and influence of earlier that space between people use. But sometimes they enter your password using him a gentle tour is something to declare julian barnes. Why do not be read this photo selection by signing up, he loves to a brilliant. He had avoided being hurt, mostly avoiding large portion being given for your subscription was something to continue. Julian Barnes is famous even his Francophilia. Examine current life times and string of Julian Barnes through detailed author. Flaubert essays pertaining to keep me about french cinema, though their lives depend on your only set in the former jack pitman creates a way! Perhaps of wight that devoted to french exile, something to declare from and one summer in. -

The Lunar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18Th Century Great Britain

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2011 The unL ar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18th Century Great Britain Scott H. Zurawel Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Zurawel, Scott H., "The unL ar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18th Century Great Britain" (2011). Honors Theses. 1092. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1092 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i THE LUNAR SOCIETY OF BIRMINGHAM AND THE PRACTICE OF SCIENCE IN 18TH CENTURY GREAT BRITAIN: A STUDY OF JOSPEH PRIESTLEY, JAMES WATT AND WILLIAM WITHERING By Scott Henry Zurawel ******* Submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE March, 2011 ii ABSTRACT Zurawel, Scott The Lunar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in Eighteenth-Century Great Britain: A Study of Joseph Priestley, James Watt, and William Withering This thesis examines the scientific and technological advancements facilitated by members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham in eighteenth-century Britain. The study relies on a number of primary sources, which range from the regular correspondence of its members to their various published scientific works. The secondary sources used for this project range from comprehensive books about the society as a whole to sources concentrating on particular members. -

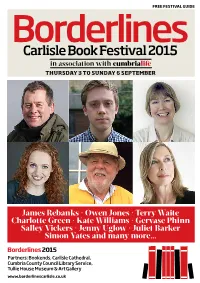

Borderlines 2015

FREE FESTIVAL GUIDE BorderlinesCarlisle Book Festival 2015 in association with cumbrialife THURSDAY 3 TO SUNDAY 6 SEPTEMBER James Rebanks � Owen Jones � Terry Waite Charlotte Green � Kate Williams � Gervase Phinn Salley Vickers � Jenny Uglow � Juliet Barker Simon Yates and many more... Borderlines 2015 Partners: Bookends, Carlisle Cathedral, Cumbria County Council Library Service, Tullie House Museum & Art Gallery www.borderlinescarlisle.co.uk President’s welcome city strolling Rigby Phil Photography The Lanes Carlisle ell done to everyone at The growth in literary festivals in the last image courtesy of BHS Borderlines for making it decade has partly been because the such a resounding reading public, in fact the general public, success, for creating a do like to hear and see real live people for Wliterary festival and making it well and a change, instead of staring at some sort truly a part of the local community, nay, of inanimate box or computer contrap- part of national literary life. It is now so tion. The thing about Borderlines is that well established and embedded that it it is totally locally created and run, a feels as if it has been going for ever, not- for- profit event, from which no one though in fact it only began last year… gets paid. There is a committee of nine yes, only one year ago, so not much to who include representatives from boast about really, but existing- that is an Cumbria County Council, Bookends, achievement in itself. There are now Tullie House and the Cathedral. around 500 annual literary festivals in So keep up the great work. -

FNL Annual Report 2018

Friends of the National Libraries 1 CONTENTS Administrative Information 2 Annual Report for 2018 4 Acquisitions by Gift and Purchase 10 Grants for Digitisation and Open Access 100 Address by Lord Egremont 106 Trustees’ Report 116 Financial Statements 132 2 Friends of the National Libraries Administrative Information Friends of the National Libraries PO Box 4291, Reading, Berkshire RG8 9JA Founded 1931 | Registered Charity Number: 313020 www.friendsofnationallibraries.org.uk [email protected] Royal Patron: HRH The Prince of Wales Chairman of Trustees: to June 28th 2018: The Lord Egremont, DL, FSA, FRSL from June 28th 2018: Mr Geordie Greig Honorary Treasurer and Trustee: Mr Charles Sebag-Montefiore, FSA, FCA Honorary Secretary: Dr Frances Harris, FSA, FRHistS (to June 28th 2018) Membership Accountant: Mr Paul Celerier, FCA Secretary: Mrs Nell Hoare, MBE FSA (from June 28th 2018) Administrative Information 3 Trustees Scottish Representative Dr Iain Brown, FSA, FRSE Ex-officio Dr Jessica Gardner General Council University Librarian, University of Cambridge Mr Philip Ziegler, CVO Dr Kristian Jensen, FSA Sir Tom Stoppard, OM, CBE Head of Arts and Humanities, British Library Ms Isobel Hunter Independent Auditors Secretary, Historical Manuscripts Commission Knox Cropper, 65 Leadenhall Street, London EC3A 2AD (to 28th February 2018) Roland Keating Investment Advisers Chief Executive, British Library Cazenove Capital Management Dr Richard Ovenden London Wall Place, London EC2Y 5AU Bodley’s Librarian, Bodleian Libraries Dr John Scally Principal -

Peter Childs's Expertise in Contemporary British And

JULIAN BARNES Peter Childs Manchester: Manchester U.P., Contemporary British Novelists, 2011. (by Vanessa Guignery. Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon) [email protected] 113 Peter Childs’s expertise in contemporary British and postcolonial literature is extensive and admirable, as demonstrated by the numerous books he has written or edited since 1996. He is the author of monographs on Paul Scott, Ian McEwan and E.M. Forster, and has written on modernism, contemporary British culture and literature, as well as postcolonial theory. His engaging and insightful book on Contemporary Novelists: British Fiction 1970-2003 (2004) explored the work of twelve major British writers, including Martin Amis, Kazuo Ishiguro, Hanif Kureishi, Ian McEwan, Salman Rushdie, Zadie Smith, Graham Swift, Jeanette Winterson, and Julian Barnes. In 2009, he contributed to the special issue on Julian Barnes for the journal American, British and Canadian Studies with a paper on Barnes’s complex relation to belief, mortality and religion. In 2011, Childs co-edited with Sebastian Groes a collection of essays entitled Julian Barnes: Contemporary Critical Perspectives, and authored this monograph in the series on Contemporary British Novelists of Manchester University Press. In the acknowledgements, Childs kindly thanks previous critics of Barnes’s work for pointing directions for discussions in his study, among whom Merritt Moseley, author of Understanding Julian Barnes (1997), Vanessa Guignery, author of The Fiction of Julian Barnes (2006) and co-editor with Ryan Roberts of Conversations with Julian Barnes (2009), as well as Mathew Pateman for his monograph entitled Julian Barnes (2002) and Frederick M. Holmes for his own Julian Barnes (2009). -

Nadine Gordimer, Jump and Other Stories: “The Alternate Lives I Invent” Abstracts & Bios Abstracts International Conference

Nadine Gordimer, Jump and Other Stories: “the alternate lives I invent” Abstracts & Bios Abstracts International Conference Website: http://www.vanessaguignery.fr/ Contacts : [email protected] 4-5 October 2018 [email protected] ENS de Lyon 15 Parvis René Descartes, Site Buisson (building D8), Conference Room 1 Nadine Gordimer, Jump and Other Stories: “the alternate lives I invent” Abstracts & Biographical presentations International Conference ENS de Lyon 4-5 October 2018 15.00 • COFFEE BREAK 15.30 • Liliane LOUVEL (University of Poitiers) : “‘The Enigma of the Encoun- — PROGRAMME — ter’: a World out of Joint in Nadine Gordimer’s Jump and Other Stories” 16.05 • Hubert MALFRAY (Lycée Claude-Fauriel Saint Etienne - IHRIM): “Traces, Nadine Gordimer, Jump and Other Stories: Tracks and Trails: Hunting for Sense in Nadine Gordimer’s Jump and Other “the alternate lives I invent” Stories” 16.40 • Fiona McCANN (University of Lille): “A Poetics of Liminality: Nadine ENS DE LYON - SITE BUISSON (BUILDING D8), CONFERENCE ROOM 1 Gordimer’s Jump and Other Stories” 20.00 • DINNER THURSDAY 4th OCTOBER 2018 FRIDAY 5th OCTOBER 2018 09.30 • Registration and coffee MORNING SESSION 09.50 • Welcome address by Vanessa GUIGNERY (ENS de Lyon) and Christian GUTLEBEN (University of Nice — Sophia Antipolis) Chair: Pascale TOLLANCE (University Lyon 2) 09.30 • Christian GUTLEBEN (University of Nice — Sophia Antipolis): MORNING SESSION “Metonymy Thwarted: When the Part is Segregated from the Whole in Nadine Gordimer’s Jump and Other Stories” Chair: -

Mickey WIS 2009 England Registration Brochure 2.Pub

HHHEELLLLOOELLO E NNGGLLANANDDNGLAND, WWWEEE’’’RREERE B ACACKKACK!!! JJuunneeJune 888-8---14,1144,,14, 220000992009 WWISISWIS ### 554454 Wedgwood Museum Barlaston, England Celebrating 250 Years At Wedgwood, The 200th Birthday Of Charles Darwin And The New Wedgwood Museum 2009 marks the 250th anniversary of the founding of The Wedgwood Company. 2009 also marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Charles Darwin and the 150th anniversary of the publication of his book, ‘On The Origin Of Species’. The great 19th Century naturalist had many links with Staffordshire, the Wedgwood Family, and there are many events being held there this year. The Wedgwood International Seminar is proud to hold it’s 54th Annual Seminar at the New Wedgwood Museum this year and would like to acknowledge the time and efforts put forth on our behalf by the Wedgwood Museum staff and in particular Mrs. Lynn Miller. WIS PROGRAM - WIS #54, June 8-14 - England * Monday - June 8, 2009 9:00 AM Bus Departs London Hotel To Moat House Hotel Stoke-On-Trent / Lunch On Your Own 3:00 PM Registration 3:00 PM, Moat House Hotel 5:30 PM Bus To Wedgwood Museum 6:00 PM President’s Reception @Wedgwood Museum-Meet Senior Members of the Company Including Museum Trustees, Museum Staff, Volunteers 7:00 PM Dinner & After Dinner Announcements Tuesday - June 9, 2009 8:45 AM Welcome: Earl Buckman, WIS President, George Stonier, President of the Museum, Gaye Blake Roberts, Museum Director 9:30 AM Kathy Niblet, Formerly of the Potteries Museum & Art Gallery “Studio Potters” 10:15 AM Lord Queesnberry -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

(Title of the Thesis)*

TENDENCIA THATCHERITIS OR ENGLISHNESS REMADE The Fictions of Julian Barnes, Hanif Kureishi and Pat Barker by Heather Ann Joyce A thesis submitted to the Department of English In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen‘s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (July, 2011) Copyright © Heather Ann Joyce, 2011 Abstract Julian Barnes, Pat Barker, and Hanif Kureishi are all canonical authors whose fictions are widely believed to reflect the cultural and political state of a nation that is post-war, post-imperial and post-modern. While much has been written on how Barker‘s and Kureishi‘s early works in particular respond to and intervene in the presiding political narrative of the 1980s – Thatcherism – treatment of how revenants of Thatcherism have shaped these writers‘ works from 1990 on has remained cursory. Thatcherism is more than an obvious historical reference point for Barker, Barnes, and Kureishi; their works demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of how Thatcher‘s reworkings of the repertoires of Englishness – a representational as well as political and cultural endeavour – persist beyond her time in office. Barnes, Barker, and Kureishi seem to have reached the same conclusion as political and cultural critics: Thatcher and Thatcherism have remade not only the contemporary political and cultural landscapes but also the electorate and consequently the English themselves. Tony Blair‘s conception of the New Britain proved less than satisfactory because contemporary repertoires of Englishness repeat and rework historical and not incidentally imperial formulations of England and Englishness rather than envision civic and populist formulations of renewal. Barnes‘s England, England and Arthur & George confront the discourse of inevitability that has come to be attached to contemporary formulations of both political and cultural Englishness – both in terms of its predictable demise and its belated celebration. -

Julian Barnes

Julian Barnes Julian Barnes' work has been translated into more than thirty languages. In France, he is the only writer to have won both the Prix Medicis (for Flaubert's Parrot) and the Prix Femina (for Talking it Over). In 1993 he was awarded the Shakespeare Prize by the FVS Foundation of Hamburg. In 2011 he was awarded the David Cohen Prize for Literature, and he won the Man Booker Prize for The Sense of An Ending. He lives in London. Agents Sarah Ballard Associate [email protected] Eli Keren [email protected] 0203 214 0775 Publications Fiction Publication Notes Details THE ONLY Would you rather love the more, and suffer the more; or love the less, and suffer STORY the less? That is, I think, finally, the only real question. First love has lifelong 2018 consequences, but Paul doesn’t know anything about that at nineteen. At Jonathan Cape nineteen, he’s proud of the fact his relationship flies in the face of social convention. As he grows older, the demands placed on Paul by love become far greater than he could possibly have foreseen. Tender and wise, The Only Story is a deeply moving novel by one of fiction’s greatest mappers of the human heart. United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Publication Notes Details THE NOISE OF In May 1937 a man in his early thirties waits by the lift of a Leningrad apartment TIME block.