Norman Bates As “One of Us”: Freakery in Alfred Hitchcock's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Search for Spectators: Vistavision and Technicolor in the Searchers Ruurd Dykstra the University of Western Ontario, [email protected]

Kino: The Western Undergraduate Journal of Film Studies Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 1 2010 The Search for Spectators: VistaVision and Technicolor in The Searchers Ruurd Dykstra The University of Western Ontario, [email protected] Abstract With the growing popularity of television in the 1950s, theaters experienced a significant drop in audience attendance. Film studios explored new ways to attract audiences back to the theater by making film a more totalizing experience through new technologies such as wide screen and Technicolor. My paper gives a brief analysis of how these new technologies were received by film critics for the theatrical release of The Searchers ( John Ford, 1956) and how Warner Brothers incorporated these new technologies into promotional material of the film. Keywords Technicolor, The Searchers Recommended Citation Dykstra, Ruurd (2010) "The Search for Spectators: VistaVision and Technicolor in The Searchers," Kino: The Western Undergraduate Journal of Film Studies: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Dykstra: The Search for Spectators The Search for Spectators: VistaVision and Technicolor in The Searchers by Ruurd Dykstra In order to compete with the rising popularity of television, major Hollywood studios lured spectators into the theatres with technical innovations that television did not have - wider screens and brighter colors. Studios spent a small fortune developing new photographic techniques in order to compete with one another; this boom in photographic research resulted in a variety of different film formats being marketed by each studio, each claiming to be superior to the other. Filmmakers and critics alike valued these new formats because they allowed for a bright, clean, crisp image to be projected on a much larger screen - it enhanced the theatre going experience and brought about a re- appreciation for film’s visual aesthetics. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

NECROPHILIC and NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS Approval Page

Running head: NECROPHILIC AND NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS Approval Page: Florida Gulf Coast University Thesis APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Christina Molinari Approved: August 2005 Dr. David Thomas Committee Chair / Advisor Dr. Shawn Keller Committee Member The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. NECROPHILIC AND NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS 1 Necrophilic and Necrophagic Serial Killers: Understanding Their Motivations through Case Study Analysis Christina Molinari Florida Gulf Coast University NECROPHILIC AND NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS 2 Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Literature Review............................................................................................................................ 7 Serial Killing ............................................................................................................................... 7 Characteristics of sexual serial killers ..................................................................................... 8 Paraphilia ................................................................................................................................... 12 Cultural and Historical Perspectives -

America's Fascination with Multiple Murder

CHAPTER ONE AMERICA’S FASCINATION WITH MULTIPLE MURDER he break of dawn on November 16, 1957, heralded the start of deer hunting T season in rural Waushara County, Wisconsin. The men of Plainfield went off with their hunting rifles and knives but without any clue of what Edward Gein would do that day. Gein was known to the 647 residents of Plainfield as a quiet man who kept to himself in his aging, dilapidated farmhouse. But when the men of the vil- lage returned from hunting that evening, they learned the awful truth about their 51-year-old neighbor and the atrocities that he had ritualized within the walls of his farmhouse. The first in a series of discoveries that would disrupt the usually tranquil town occurred when Frank Worden arrived at his hardware store after hunting all day. Frank’s mother, Bernice Worden, who had been minding the store, was missing and so was Frank’s truck. But there was a pool of blood on the floor and a trail of blood leading toward the place where the truck had been garaged. The investigation of Bernice’s disappearance and possible homicide led police to the farm of Ed Gein. Because the farm had no electricity, the investigators con- ducted a slow and ominous search with flashlights, methodically scanning the barn for clues. The sheriff’s light suddenly exposed a hanging figure, apparently Mrs. Worden. As Captain Schoephoerster later described in court: Mrs. Worden had been completely dressed out like a deer with her head cut off at the shoulders. -

Frequencies Between Serial Killer Typology And

FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS A dissertation presented to the faculty of ANTIOCH UNIVERSITY SANTA BARBARA in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY in CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY By Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori March 2016 FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS This dissertation, by Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori, has been approved by the committee members signed below who recommend that it be accepted by the faculty of Antioch University Santa Barbara in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Committee: _______________________________ Ron Pilato, Psy.D. Chairperson _______________________________ Brett Kia-Keating, Ed.D. Second Faculty _______________________________ Maxann Shwartz, Ph.D. External Expert ii © Copyright by Leryn Rose-Doggett Messori, 2016 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT FREQUENCIES BETWEEN SERIAL KILLER TYPOLOGY AND THEORIZED ETIOLOGICAL FACTORS LERYN ROSE-DOGGETT MESSORI Antioch University Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, CA This study examined the association between serial killer typologies and previously proposed etiological factors within serial killer case histories. Stratified sampling based on race and gender was used to identify thirty-six serial killers for this study. The percentage of serial killers within each race and gender category included in the study was taken from current serial killer demographic statistics between 1950 and 2010. Detailed data -

Adam Gopnick

WERNER HERZOG IN CONVERSATION WITH PAUL HOLDENGRÄBER WAS THE 20th CENTURY A MISTAKE? February 16, 2007 Celeste Bartos Forum New York Public Library WWW.NYPL.ORG/LIVE NATHANIEL KAHN: Hello. Okay, thank you for coming to the New York Public Library—and I have a couple of brief—I’m Nathaniel Kahn and I have a couple of—can everybody hear back there? A couple of brief notes, first of all thank you very much for joining us tonight. And this is a promotional offer—we’re happy to offer each person who signs up on our e-mail list, one free ticket to a LIVE from the New York Public Library program in the Spring 07 season. Just to give you a little preview of the coming events. On March 7th, Paul has a conversation with William T. Vollmann and it’s called “Are You Poor?” and the answer for all of us is probably yes. March 10th, Mira Nair and Jhumpa Lahiri, March 26th, Clive James in conversation with Paul Holdengräber, and that’s called “Cultural Amnesia.” And lastly, we encourage you to become a Friend of the library and support these wonderful events, and LIVE from the NYPL, Werner Herzog in conversation with Paul Holdengräber, 2/16/07, page 1 they are wonderful, at LIVE from the New York Public Library, and you can sign up at the Friends table. This is an enormous honor for me to introduce Werner Herzog, who needs no introduction from me, but when Paul asked me to introduce him, of course I said yes—how can you not say yes to introducing your hero?—even if it is a little like asking the ant to introduce the elephant. -

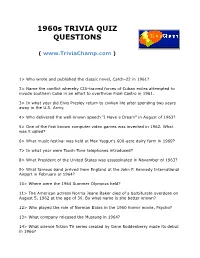

1960S TRIVIA QUIZ QUESTIONS

1960s TRIVIA QUIZ QUESTIONS ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> Who wrote and published the classic novel, Catch-22 in 1961? 2> Name the conflict whereby CIA-trained forces of Cuban exiles attempted to invade southern Cuba in an effort to overthrow Fidel Castro in 1961. 3> In what year did Elvis Presley return to civilian life after spending two years away in the U.S. Army. 4> Who delivered the well-known speech "I Have a Dream" in August of 1963? 5> One of the first known computer video games was invented in 1962. What was it called? 6> What music festival was held at Max Yasgur's 600-acre dairy farm in 1969? 7> In what year were Touch-Tone telephones introduced? 8> What President of the United States was assassinated in November of 1963? 9> What famous band arrived from England at the John F. Kennedy International Airport in February of 1964? 10> Where were the 1964 Summer Olympics held? 11> The American actress Norma Jeane Baker died of a barbiturate overdose on August 5, 1962 at the age of 36. By what name is she better known? 12> Who played the role of Norman Bates in the 1960 horror movie, Psycho? 13> What company released the Mustang in 1964? 14> What science fiction TV series created by Gene Roddenberry made its debut in 1966? 15> What well-known board game made its modern day version debut in 1960? 16> Who wrote and published the classic novel, To Kill a Mockingbird in 1960? Answers: 1> Joseph Heller - He began writing the novel in 1953. -

The Skin and the Protean Body in Pedro Almodóvar's Body Horror

humanities Article Destruction, Reconstruction and Resistance: The Skin and the Protean Body in Pedro Almodóvar’s Body Horror The Skin I Live In Subarna Mondal Department of English, The Sanskrit College and University, Kolkata 700073, India; [email protected] Abstract: The instinct to tame and preserve and the longing for eternal beauty makes skin a crucial element in the genre of the Body Horror. By applying a gendered reading to the art of destruction and reconstruction of an ephemeral body, this paper explores the significant role of skin that clothes a protean body in Almodóvar’s unconventional Body Horror, “The Skin I Live In” (2011). Helpless vulnerable female bodies stretched on beds and close shots of naked perfect skin of those bodies are a frequent feature in Almodóvar films. Skin stained and blotched in “Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!” (1989), nurtured and replenished in “Talk to Her” (2002), patched up and stitched in “The Skin I Live In”, becomes a key ingredient in Almodóvar’s films that celebrate the fluidity of human anatomy and sexuality. The article situates “The Skin I Live In” in the filmic continuum of Body Horrors that focus primarily on skin, beginning with Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho” (1960), and touching on films like Jonathan Demme’s “The Silence of the Lambs” (1991) and Tom Tykwer’s “Perfume: The Story of a Murderer” (2006) and attempts to understand how the exploited bodies that have been culturally and socially subjugated have shaped the course of the history of Body Horrors in cinema. In “The Skin I Live In” the destruction of Vicente’s body and its recreation into Vera follow a mad scientist’s urge to dominate an unattainable body, but this ghastly assault on the body has the onscreen appearance of a routine surgical operation by an expert cosmetologist in a well-lit, sanitized mise-en-scène, Citation: Mondal, Subarna. -

The Cemetery Artist Ed Gein: a True American Horror Story a Film by Brian Lee Tucker

The Cemetery Artist / Ed Gein: a True American Horror Story The Cemetery Artist Ed Gein: a True American Horror Story A film by Brian Lee Tucker 1 The Cemetery Artist / Ed Gein: a True American Horror Story FADE IN EXT. THE GEIN FAMILY FARM – 1922 – DAY {A sixteen year old ED GEIN is raking leaves with his brother, HENRY, in the front yard. ED stops raking and glances around, whispering to HENRY.} ED: I got a half pint of dad’s stash. HENRY: {mortified} are you nuts? What if he notices it’s missing? ED: He won’t, come on. EXT. BEHIND THE BARN {ED and HENRY are sitting on a bale of hay passing the bottle back and forth when their mother, AUGUSTA, comes sneaking around the corner, surprising them. She is carrying a long switch made from a sticker bush in one hand and a Bible in the other. She is a fervent Lutheran, always preaching to her boys about the innate immorality of the world, the evil of drinking, and the belief that all women were naturally prostitutes and instruments of the devil. She reserved time every afternoon to read to them from the Bible, usually selecting graphic verses from the Old Testament concerning death, murder, and divine retribution. Henry and Ed have remained detached from people outside of their farmstead, and had only each other for company.} 2 The Cemetery Artist / Ed Gein: a True American Horror Story AUGUSTA: Ah-ha! Gotcha! HENRY: But mama, Ed made me- AUGUSTA: Don’t bother with your lies, Henry Gein. -

(Literary) Special Effect: (Inter)Mediality in the Contemporary US-American Novel and the Digital Age

The (Literary) Special Effect: (Inter)Mediality in the Contemporary US-American Novel and the Digital Age Dissertation zur Erlangung des philosophischen Doktorgrades an der Philosophischen Fakultät der Georg-August-Universität Göttingen vorgelegt von Bogna Kazur aus Lodz, Polen Göttingen 2018 Contents 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 3 2 The Question of Medium Specificity in the Digital Age .................................................. 29 3 House of Leaves (2000) and the Uncanny Dawn of the Digital........................................ 39 3.1 Digital Paranoia: Arriving on Ash Tree Lane ........................................................... 39 3.2 Writing about House of Leaves ................................................................................. 43 3.3 Intermedial Overabundance: Taming House of Leaves ............................................. 49 3.4 An “Explicit” Approach to the Digital Age ............................................................... 54 3.5 What Kind of Movie is THE NAVIDSON RECORD? ..................................................... 68 4 In the Midst of the Post-Cinematic Age: Marisha Pessl’s Night Film (2013) .................. 88 4.1 Meant for Adaptation: Night Film and the Fallacy of First Impressions ................... 88 4.2 The Post-Cinematic Reception of Film ..................................................................... 96 4.3 The Last Enigma: Cordova’s Underworld .............................................................. -

Alfred Hitchcock

High Rise Royal Opera Live: Giselle The Witch NT Live - Hangmen (Encore) Darllediad Byw / Live Satellite Screening. Peter Wright, 2016, 180m Ben Wheatley, 2016, 119m Robert Eggers, 2015, 93m Sul 10 Ebrill, 2pm, £10/£8 Sunday 10 April, 2pm, £10/£8 Cast – Tom Hiddleston, Jeremy Irons, Sienna Miller Cast – Ralph Ineson, Kate Dickie, Anya Taylor-Joy Ail ddangosiad ‘encore’ o ddrama An encore screening for this hit Mercher 6 Ebrill, 7pm £15 / £12.50 Wednesday 6 April 7pm, £15 / £12.50 Gwener 1 – Iau 7 Ebrill Friday 1 – Thursday 7 April Gwener 8 – Mercher 13 Ebrill Friday 8 – Wednesday 13 April diweddaraf Martin McDonagh. Mae production of Martin McDonagh ‘Stori gariad fwyaf swynol byd bale’ ‘Ballet’s most haunting love story’ Harry (David Morrissey) yn ddyn latest play. Harry (David Morrissey) Addasiad o nofel J.G. Ballard An adaptation of J.G.Ballard’s 1975 – Daw torcalon a brad i’r sinema - Heartbreak and betrayal come Llwyddiant enfawr ‘word of mouth’, A huge word of mouth hit and an enwog ac adnabyddus, ond beth is something of a local celebrity. o 1975. Hanes Robert Laing, novel. The film centres around gyda dangosiad byw o gynhyrchiad to the cinema with a live screening ffilm arswyd eithriadol o iasol sy’n exceptionally creepy horror film yw dyfodol ail grogwr gorau Lloegr But what’s the second-best doctor ifanc sy’n cael ei ddenu Robert Laing, a young doctor who syfrdanol y Bale Brenhinol o’r of The Royal Ballet’s breath-taking ein taflu nôl mewn amser at deulu which plunges us back in time ar ddiwrnod pan fydd yr arfer o hangman in England to do on the gan floc tŵr preswyl a’i grëwr is seduced by a residential tower clasur Giselle. -

The Meaning of the Western Movie

sCott a. mCConnEll The Meaning of the Western Movie emember Shane, Bonanza and The Lone of the country. Ranger? In novel, film and television, west- For more than 150 years, especially since erns once ruled the range. Until the 1960s 1900 when the frontier period was ending, the Rwesterns were the most popular fiction genre and American West was revealed in the western novel. remained popular until the 1970s. In his book The Influential among these were Whispering Smith Searchers the western historian Glenn Frankel tells (Frank Spearman, 1906), Riders of the Purple Sage us that western novels “consistently outsold all gen- (Zane Grey, 1912), Destry Rides Again (Max Brand, res, including the closest competitor, the detective 1930) and True Grit (Charles Portis, 1968). With the story—whose protagonist was, after all, just another arrival of television in the United States in 1947, version of the Western hero”. Frankel notes that “of the western and its view of America dominated the 300 million paperbacks sold in 1956, one third the small screen for many years. Some of the most were westerns”. influential shows and stars during the television Western films were similarly popular. As Frankel western heyday included The Lone Ranger (star- reports, “Westerns by the mid-1950s accounted for ring Clayton Moore), Rawhide (Clint Eastwood), one third of the output of the major studios and half Bonanza (Michael Landon) and Gunsmoke (James the output of the smaller independents.” Incredibly, Arness). “well over seven thousand Westerns have been To most people, however, westerns are movies. made”. The American Film Institute (AFI) has defined Westerns were even more popular on television.