Theological Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Eucharist : the Church in the Heart of Christ

THE EUCHARIST : THE CHURCH IN THE HEART OF CHRIST by Rev. Fr. Daniel Meynen, D.D. http://meynen.homily−service.net/ Translation from the French by Antoine Valentim http://web.globalserve.net/~bumblebee/ © 1995−2004 − Daniel Meynen How the Church offers herself to the Father − in Christ with the Holy Spirit for Mary Mediatrix TABLE OF CONTENTS By way of preface 5 Introduction 11 Chapter I Fundamental principles of Mary Mediatrix 19 Chapter II John 6:57 : The powerful Virgin of the Nativity 29 Chapter III Mary Mediatrix : Mother of the Church 39 Chapter IV The Pope : Spouse of Mary in Christ 51 Chapter V Eternal salvation through Mary, and for Mary 63 Conclusion 75 3 BY WAY OF PREFACE The Eucharist: the Church in the Heart of Christ, that is the title of this book. Certainly, all of Christ is present in the Eucharist, his heart as well as all of his body, all his soul, and all the Divinity of the Word of Life that he is in person. But the Heart of Christ truly seems to be the explanatory sign of all the Eucharist: it is the human symbol of all of God’s Love for his Church, which he has redeemed at the cost of his Blood shed on the Cross of Calvary. And love does not have a reason; or if it does, it is love itself that is its own reason. Love can only be explained by love, which is the fullness of its reason. There is therefore no reason that more fully or more completely explains the Eucharist than the very Love of God, symbolized by the Heart of Christ. -

702 and It Is Disheartening That the Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu

702 Book Reviews and it is disheartening that the Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu cannot ensure for its readers (and its authors) a higher standard of comprehensibil- ity in an English-language publication. German is the original language of the work (in the form of a habilitation thesis) and a perfectly respectable interna- tional academic language. Sobiech should have left Jesuit Prison Ministry in it. All of this adds up to a study that is solidly researched and encyclopedically helpful, but also frustratingly hard to read. Scholars will most profitably turn to it as an overview of particular topics and a finder’s guide for source material related to their own research. The best future work on early modern carceral pastoral care, the life of Friedrich Spee, and his Cautio criminalis will undoubt- edly be built on foundations Sobiech lays here. Spee deserves a study on a par with Machielsen’s on Delrio; thanks to Sobiech, we are one step closer. David J. Collins, S.J. Georgetown University, Washington, DC, usa [email protected] doi:10.1163/22141332-00704008-16 Ralph Dekoninck, Agnès Guiderdoni, and Clément Duyck, eds. Maximilianus Sandæus, un jésuite entre mystique et symbolique. Études suivies de l’édition par Mariel Mazzocco des annotations d’Angelus Silesius à la Pro theologia mystica clavis. Mystica 13. Paris: Honoré Champion, 2019. Pp. 398. Pb, €55.00. The Jesuit Maximilianus Sandaeus (Max van der Sandt, 1578–1656), who was born in Amsterdam but worked primarily in German-speaking lands, teaching theology and exegesis, and who represented his province at the Eighth General Congregation that elected Vincenzo Carafa as general superior in 1646, wrote an impressive oeuvre. -

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS THEOLOGY AND EVOLUTION. By various writers. Edited by E. C. Mes senger. Westminster, Md.: Newman, 1952. Pp. vi + 337. $4.50. The recently deceased editor-author has called this volume a sequel to his earlier Evolution and Theology (London, 1931; N. Y., 1932). Part I (pp. 1-216) is especially deserving of this designation. Entitled "Essays on Evo lution," it collects fourteen critical reviews or commentaries written by various theologians soon after the appearance of the 1931 volume. To many of these essays is added, in full, the subsequent published exchange between author and critic. The discussion is frequently closed with a summary com ment by Dr. Messenger in his present role of editor. Critics who figure in Part I include P. G. M. Rhodes, R. W. Meagher, B. C. Butler, O.S.B., P. J. Flood, J. O. Morgan, Michael Browne, W. H. McClellan, S J., W. J. McGarry, S J., E. F. Sutclifïe, S J., Al. Janssens, J. Bittremieux, A. Brisbois, S.J., J. Gross, and Père Lagrange, O.P. All con cede the significance of Evolution and Theology as the first full-length treat ment of the subject from the theological and scriptural viewpoint, but not all admit the treatment to have been fair. Judgments of "inconsistency" and "special pleading" occur more than a few times. Aside from disagreements with his interpretations of the pertinent writ ings of Gregory of Nyssa and Augustine, and with his understanding of St. Thomas' treatment of the form in Adam's body, the criticism most gen erally leveled at Dr. -

FACULTY of ARTS, UNIVERSITY of JAFFNA Centre for Open and Distance Learning (CODL) BACHELOR of ARTS DEGREE PROGRAM

FACULTY OF ARTS, UNIVERSITY OF JAFFNA Centre for Open and Distance Learning (CODL) BACHELOR OF ARTS DEGREE PROGRAM Structure of the Degree programme 1.0 Introduction In accordance with the re-structuring of existing External Degree Program as per the Commission Circular no 932, Faculty of Arts, University of Jaffna, proposing a new structure, incorporating the provisions of the credit valued system. The new regulations shall be effective for the new entrants of the forthcoming academic year 2011/2012 onwards. 2.0 Structure of study program All study programs have designed to suit the semester based course unit system and Grade Point Average (GPA) evaluation and marking scheme. 2.1 Degrees The Faculty of Arts offers the following Degree programs. 2.1.1 B.A general Degree program of 03 years duration. (SLQF level – 05) 2.1.2 B.A special degree program of 04 years duration. (SLQF level – 06) The General Degree program offers a minimum of 90 credits, to be completed within a period of 03 years. (06 semesters of 20 weeks duration including examination period), with provision to extend up to a maximum of 06 years, depending on the students choice. The Special Degree program offers minimum of 120 credits, to be completed within a period of 04 years. (08 semesters of 20 week duration including examination period), with provision to extend maximum of 08 years, depending on the students choice. One credit is equivalent to 30 hours of contact hours (face to face instructions, tutorial, lab classes, if any, online or computer based learning, independent learning and examinations). -

The Reformation of Hell? Protestant and Catholic Infernalisms in England, C

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap This paper is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our policy information available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this paper please visit the publisher’s website. Access to the published version may require a subscription. Author(s): PETER MARSHALL Article Title: The Reformation of Hell? Protestant and Catholic Infernalisms in England, c. 1560–1640 Year of publication: 2010 Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022046908005964 Publisher statement: © Cambridge University Press 2010 Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 61, No. 2, April 2010. f Cambridge University Press 2010 279 doi:10.1017/S0022046908005964 The Reformation of Hell? Protestant and Catholic Infernalisms in England, c. 1560–1640 by PETER MARSHALL University of Warwick, UK E-mail: [email protected] Despite a recent expansion of interest in the social history of death, there has been little scholarly examination of the impact of the Protestant Reformation on perceptions of and discourses about hell. Scholars who have addressed the issue tend to conclude that Protestant and Catholic hells differed little from each other in the Elizabethan and early Stuart periods. This article undertakes a comparative analysis of printed English-language sources, and finds significant disparities on questions such as the location of hell and the nature of hell-fire. It argues that such divergences were polemically driven, but none the less contributed to the so-called ‘decline of hell’. -

Dr. Gloria V.Dhas

Dr. Gloria V.Dhas Head of the Department Department of Christian Tamil Studies Mobile No: 9865627359 School of Religions, Philosphy and Humanist Thought Email:[email protected] Educational Qualifications : M.A.,M.A., M.Ed., PG.Dip.Sikh., PG.Dip.Yoga.,M.Phil., Ph.D Professional Experience : 23 Year FIELD OF SPECIALIZATION . Literature . Comparative Religion . Ecology, Feminism and Dalit Philospy RESEARCH SPECIALIZATION . Tamil Literature . Social Changes through Religions . Transformation by Social Services Research Supervision: Program Completed Ongoing Ph.D 5 7 M.Phil 35 2 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE No Institution Position From (date) To (date) Duration 1 Lady Doak College 23.11.1992 01.11.1993 One Year Lecturer 2 Lady Doak College 27.01.1994 16.04.1994 Three Lecturer MOnths 3 Avinasilingam 19.10.1994 15.05.1995 Eight Deemed Project Assistant Months University, Coimbator. 4 Madurai Kamaraj 18.05.1995 17.05.2000 Five University Research Associate Years Madurai - 21 5 Madurai Kamaraj 02.07.2000 30.04.2001 Ten University Teaching Assistant Months Madurai - 21 6 School of 02.07.2001 30.04.2002 Ten Religions, Teaching Assistant Months Philosophy & Humanist Thought 7 School of 02.07.2002 14.10.2010 Eight Religions, Guest Lecturer Years Philosophy & Humanist Thought 8 and Head in charge Madurai Kamaraj Assistant Professor 15.03.2010 Till Date Till Date University Madurai- COMPLETED RESEARCH PROJECT No Title of the Project Funding Agency Total Grant Year 1 God Concept in CICT 2,50,000 2013‐2014 Sangam Literature HONORS/AWARDS/RECOGNITIONS . Honour Award in Lady Dock College - 1983 . Best Teacher Award in Madurai Kamaraj University - 2017 PAPER PRESENTED IN CONFERENCE/SEMINAR/WORKSHOP International Papers S.No Year Seminars 1 2015 Tradition and culture in ancient tamils, International Seminar on Katralum Karpithalum, conduted by Ministry of Singapore, and Lady Doak College, 2 2015 Madurai in Tamil Literature,Christianity in Madurai, Arulmegu Meenakshi Women’s College, Madurai. -

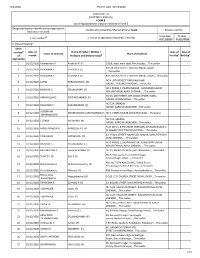

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applica Ons For

12/2/2020 Form9_AC6_02/12/2020 ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applicaons for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated locaon identy (where applicaons Constuency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Avadi Revision identy have been received) From date To date @ 2. Period of applicaons (covered in this list) 1. List number 01/12/2020 01/12/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial $ Date of Name of Father / Mother / Date of Time of number Name of claimant Place of residence of receipt Husband and (Relaonship)# hearing* hearing* applicaon 1 01/12/2020 Manikandan K Krishnan R (F) 135/8, avadi main road, Paruthipau, , Thiruvallur #20, BOUND STREET, KOVILPATHAGAI, AVADI 2 01/12/2020 PRASANNA E ELANGO R (F) , , Thiruvallur 3 01/12/2020 PRASANNA E ELANGO R (F) #20, BOUND STREET, KOVILPATHAGAI, AVADI, , Thiruvallur NO 6 , 8TH STREET THIRUVALLUVAR 4 01/12/2020 LATHA PARAMASIVAM (H) NAGAR, THIRUMULLAIVOYAL, , Thiruvallur NO 5 PHASE 1, SWATHI NAGAR , KANNADAPALAYAM 5 01/12/2020 BHAVANI S SELVAKUMAR (F) KOVILPATHAGAI AVADI CHENNAI , , Thiruvallur NO 26, 2ND STREET, 4TH CROSS STREET, INDRA 6 01/12/2020 AMANULLAH S SYED MOHAMED (F) NAGAR, CHOLAPURAM, , Thiruvallur NO 72A, SARADHI 7 01/12/2020 RAJAMANI C EAKAMBARAM (F) NAGAR, KARUNAKARACHERI, , Thiruvallur SUBISHANA 8 01/12/2020 DHARMAGURU LAKSHMANAN (F) NO 1, INDRA NAGAR, KOVILPADHAGAI, , Thiruvallur DHARMAGURU NO 72A, SARATHI 9 01/12/2020 C GIRIJA RAJAMANI (H) NAGAR, KARUNAKARACHERI, , Thiruvallur PLOT NO 91, 6 TH STREET THIRUMALAI VASAN NAGAR S 10 01/12/2020 MANU RAMESH R RAMESAN P G (F) M NAGAR POST, -

Download Download

Early Modern Women: An Interdiciplinary Journal 2006, vol. 1 Maladies up Her Sleeve? Clerical Interpretation of a Suffering Female Body in Counter-Reformation Spain1 Susan Laningham n the second Sunday of Lent in 1598, just as she was about to take Othe holy wafer of communion in the convent of Santa Ana in Ávila, Spain, a thirty-seven-year-old Cistercian nun named María Vela found she could not open her mouth.2 Shocked witnesses reported that María’s jaws were clenched “as if they were nailed,” and no one could wrench them apart. Over the next year, María’s mysterious ailment occurred intermit- tently, sometimes only on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. The Cisterican sisters would rush early to her room on those mornings, hoping to get her to eat before the malady reappeared, only to find her teeth already clamped shut.3 Complicating the situation was a host of other inexplicable physical ailments: a distended abdomen that arched her spine to the breaking point, hands knotted in a vice-like grip,4 violent tremors, and raging fevers. There were also the illnesses that normally plagued María: spasms in her joints, fluid in her lungs, vertigo, and seizures that some attributed to epilepsy. Accommodations were made for her, not simply because she ailed or came from a distinguished Spanish family,5 but because she claimed that heav- enly visions and voices had revealed to her that all her excruciating pains were sent from God. Since many of her illnesses defied diagnosis, she was fast becoming a topic of unremitting gossip inside and outside the convent walls. -

The Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture THE CRISTOS YACENTES OF GREGORIO FERNÁNDEZ: POLYCHROME SCULPTURES OF THE SUPINE CHRIST IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY SPAIN A Dissertation in Art History by Ilenia Colón Mendoza © 2008 Ilenia Colón Mendoza Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2008 The dissertation of Ilenia Colón Mendoza was reviewed and approved* by the following: Jeanne Chenault Porter Associate Professor Emeritus of Art History Dissertation Co-Advisor Co-Chair of Committee Brian A. Curran Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Co-Advisor Co-Chair of Committee Elizabeth J. Walters Associate Professor of Art History Simone Osthoff Associate Professor of Art Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head of the Department of Art History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract The Cristo yacente, or supine Christ, is a sculptural type whose origins date back to the Middle Ages. In seventeenth-century Spain these images became immensely popular as devotional aids and vehicles for spiritual contemplation. As a form of sacred drama these sculptures encouraged the faithful to reflect upon the suffering, death, and Resurrection of Christ as well as His promise of salvation. Perhaps the most well-known example of this type is by the Valladolidian sculptor, Gregorio Fernández (1576-1636). Located in the Capuchin Convent of El Pardo near Madrid, this work was created in accordance with Counter-Reformation mandates that required religious images inspire both piety and empathy. As a “semi-narrative”, the Cristo yacente encompasses different moments in the Passion of Christ, including the Lamentation, Anointment, and Entombment. -

Renouveau Et Œcuménisme Table Des Matières

No 3 | Juillet 2017 En bonne forme Renouveau et œcuménisme Table des matières 42028Il n’y a de changement Il y a 8 siècles, François d’Assise Nouvelle forme? Pas du tout, possible sans volonté. réalise bien qu’il n’y a pas de c’est le style de Jésus. compréhension de l’autre sans le rencontrer. 4 Une Eglise sans les femmes? Inimaginable Tour d’horizon dans les diocèses 8 Les communautés nouvelles: une chance et un défi Un regard sur la Suisse romande 12 Vie franciscaine – Panorama suisse Une découverte 16 Les deux fenêtres de Nicolas de Flue Une approche originale de notre saint national 18 Karl Barth: «Frère Nicolas demeure également notre saint» Un médiateur entre catholiques et protestants 20 François d’Assise: un réformateur bien avant la Réforme Déjà des mouvements précurseurs au Moyen-Age 26 Le Pape François et l’œcuménisme «Pour que tous soient un» 28 Le Pape François et ses tentatives de réforme Les objectifs du Pape jésuite 30 Retour à une vie plus responsable Réflexions d’un Réformé 34 Mennonites en Bolivie: du neuf avec du vieux Un monde en mal de devenir Kaléidoscope 36 † Fr. Charles Dousse (1930–2017) 39 400 ans du couvent de Fribourg 45 Photo de couverture: Stefan Zumsteg / Impressum | Présentation Vitrail de l’église de pèlerinage «Madonna di Re», dans le Piémont 46 Lieux franciscains: Padoue – où le passé rencontre le présent 2 frères en marche 3|2017 Editorial Chères lectrices et chers lecteurs Le dimanche des Rameaux, nous avons eu à table un échange sur les changements opérés durant la Semaine Sainte, suite à la réforme liturgique sous Pie XII, dans les années cinquante. -

Father Francisco De Menezes C.Ss.R. Missionary Apostolic in India and Sri Lanka (1843-1863)

SAMUEL J. BoLAND FATHER FRANCISCO DE MENEZES C.SS.R. MISSIONARY APOSTOLIC IN INDIA AND SRI LANKA (1843-1863) ·fj SUMMARY 1. The Redemptorist. - 2. MissionarJ Apostolic in India (1843) - 3. Bombay (1843-1846) - 4. Sri Lanka (1846-1847) - 5. Monsignor de Menezes - 6. Return to Bombay. Some years ago the Spicilegium rescued from obscurity the faintly mysterious figure of the Indian Redemptorist, Father Fran 1 cisco de Menezes • Father Sampers, the author, has shown that, contrary to the assumptions of those who had scarcely known him personnally, Father de Menezes had not left the Institute on his being sent by the Sacred Congregation of Propaganda Fide to India as a Missionary Apostolic. From the material available in the gen eral archives of the Redemptorists it was possible to offer an ac count of the subject's time .in Europe, leaving to further investig ation his ministry in the Indies. The present article attempts to supply that need. There is much useful information in the files of the Sacred Congregation for the Evangelisation of the Peoples, the old Propaganda and there is probably more material to be gleaned 2 in diocesan archives in India and Sri Lanka • Further investigation of Father de Menezes certainly repays 1 A. SAMPERS, Father Francisco de Menezes, the First Asian Redemptorist in "SH" 23 (1975) 200-220. 2 The following abbreviations have been used in citing archival material: ACEP = Archivio della Sacra Congregazione per l'Evangelizzazione dei popoli. Acta = Acta S. Congregationis. LDB = Lettere e decreti della S. Congregazione e Biblietti di Monsignore Segretario. SC = Scritture riferite nei Congressi. -

9 Cartagenas.Pmd

THE INTELLECTUAL LEGACY OF THE PADRES PAÚLES AND THE RARE BOOKS COLLECTION OF SEMINARIO MAYOR DE SAN CARLOS Aloysius Lopez Cartagenas “If we encounter a man of rare intellect, we should ask him what books he reads.” -Ralph Waldo Emerson The Vincentian Fathers have been at the forefront of the formation of the Filipino clergy since the time of the Spanish occupation. They have been the administrators and formators of seminaries in different areas in the country at some point or other; in particular, the San Carlos Major Seminary in Cebu, which has been recently turned over to the diocesan clergy. The article illustrates the kind of academic, philosophical and theological training that the Vincentian Fathers have provided for the formation of the clergy in Cebu through the books and materials they have left behind, after they turned over the administration. Through this collection of books and references, some dating hundreds of years ago but are still significantly valuable, the seminary, as the paper suggests, has an indispensable tool in its hand to continue the legacy that the Vincentian Fathers have started, as far as the formation of a well-equipped, edified clergy is concerned. O n 21 March 1998, during the closing ceremonies of the school year presided over by the Archbishop of Cebu, Ricardo Cardinal Vidal, the Congregation of the Mission, represented by Fr. Manuel Ginete, formally turned over the administration of Seminario Mayor de San Carlos (Cebu City, Philippines) back to the Diocesan Clergy of Cebu. It had been more than a hundred years since the first Hapag 9, No.