I Belizean Racial Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyb Template 2012

Belize another hurricane, Hurricane Dean, hit Belize KEY FACTS affecting the livelihoods of up to 2,500 Joined Commonwealth: 1981 families in the northern parts of the country. Population: 332,000 (2013) Environment: The most significant GDP p.c. growth: 2.0% p.a. 1990–2013 environmental issues are deforestation; water UN HDI 2014: World ranking 84 pollution from sewage, industrial effluents and agricultural run-off; and solid waste Official language: English disposal. Time: GMT minus 6 hrs Vegetation: Forest covers 61 per cent of the Currency: Belizean dollar (Bz$) land area and includes rainforest with mahoganies, cayune palms, and many Geography orchids. Higher in the mountains, pine forest Area: 22,965 sq km and cedar predominate. Arable land comprises three per cent of the land area. Coastline: 386 km Wildlife: There is a strong emphasis on Capital: Belmopan conservation. By 1992, 18 national parks and Belize forms part of the Commonwealth reserves had been established, including the Belizeans descend from Mayans, Caribs, and Caribbean, and is located in Central America, world’s only jaguar reserve. Other native the many groups who came as loggers, bordering Mexico to the north and species include ocelots, pumas, baboons, settlers, refugees, slaves and imported labour: Guatemala to the west and south. Of 13 howler monkeys, toucans and many species English, Spanish, Africans and East Indians. Commonwealth member countries in the of parrot. Americas, only Belize, Canada and Guyana lie According to the 2000 census, the on the mainland, three of the most sparsely Main towns: Belmopan (capital, pop. population comprises 49 per cent Mestizos populated countries in the association; all the 18,326 in 2014), Belize City (former capital (Maya-Spanish), 25 per cent Creoles (Afro- others are islands or archipelagos. -

3434 Tues Feb 2, 2021 (9-12).Pmd

Tuesday, February 2, 2021 AMANDALABelize Page 1 NO. 3434 BELIZE CITY, TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 2, 2021 (20 PAGES) $1.00 Narco plane busted with over 2000 pounds of cocaine Nine men has since been arrested and charged. One of the men is the driver for the BDF BDF Commander’s Commander, Brigadier General Steven Ortega. driver arrested for drug plane landing LADYVILLE, Fri. Jan. 29, 2021 One of the lawmen arrested and charged in connection to the drug plane bust which took place early Friday morning was the driver of Brigadier General Steven Ortega. During an interview with the media on Friday, the BDF’s commander BELIZE DISTRICT, Fri. Jan. 29, 2021 Mexican air asset, intercepted a narco confirmed reports of the arrest On Friday morning at around 3:30 plane that departed from South America and shared that he was a.m., the Belize Police Department, with a little before 10:00 p.m. on Thursday distraught by the news. His the help of the Joint Intelligence driver, identified as Lance Operation Center (JIOC) and a Please turn to Page 19 Corporal Steve Rowland was the only BDF soldier arrested Belmopan 16-year-old Please turn toPage 3 community charged with grocer murdered murder of Curfew extended to Kenrick Drysdale 10:00 p.m. for adults BELMOPAN, Fri. Jan. 29, 2021 Late Friday afternoon, 53-year-old DANGRIGA, Stann Creek District, Belmopan resident Abel Baldarez was Thurs. Jan. 28, 2021 BELIZE CITY, Fri. Jan. 29, 2021 however, will remain unchanged, from murdered during a robbery that took On Thursday morning, January 28, The Ministry of Health and Wellness 6:00 p.m. -

Unions Rally at Memorial Park GOB Tables New Proposals to Unions

Tuesday, May 11, 2021 AMANDALABelize Page 1 NO. 3459 BELIZE CITY, TUESDAY, MAY 11, 2021 (16 PAGES) $1.00 Bondholders and GoB, no deal yet BELIZE CITY. Mon. May 10, 2021 Last week, a meeting scheduled between holders of Belize’s Super- GOB tables new bond and the Minister of State in the Ministry of Finance, Chris Coye, was proposals to unions canceled after the Creditor Committee’s representatives BELIZE CITY, Mon. May 10, 2021 indicated that the meeting would be A meeting between the Joint fruitless if Belize refuses to sign on Unions Negotiating Team and the to an IMF support plan. Government of Belize officials ended Please turn toPage 15 Please turn toPage 15 Abusive relationship ends in fatal arson by Dayne Guy St. Matthews Village, Cayo District, Mon, May 10, 2021 A mother and her 3-year-old son were reportedly burned to death in the village of St. Matthews when their home was set on fire. Her ex- common law husband is the prime suspect. According to police reports, this heinous act of arson-turned-murder occurred sometime before 11:00 o’clock on Friday night. The house of 36-year-old Kendra Middleton PM gets the jab was burnt to the ground, while she and her three-year-old child, Aiden Perez, were inside. They both perished. Unions rally at Memorial Park When firefighters arrived at the scene, the blaze had already Please turn toPage 14 Former George Street boss’s son murdered BELIZE CITY, Mon. May 10, 2021 organized resistance to salary cuts in by Dayne Guy On Friday, May 7, the members of the public sector. -

The Case for a Belizean Pan-Africanism

The Case for a Belizean Pan-Africanism by Kurt B. Young, Ph.D. Assistant Professor, Political Science & African American Studies University of Central Florida, Orlando, Florida [email protected] Abstract This essay is an analysis of Pan-Africanism in the Central American country of Belize. One of the many significant products of W.E.B. DuBois’s now famous utterance that “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line” has been the unending commitment to document the reality of the color line throughout the various regions of the African Diaspora. Thus, nearly a century after his speech at the First Pan-African Congress, this effort has produced a corpus of works on Pan-Africanism that capture the global dimensions of the Pan- African Movement. However, the literature on Pan-Africanism since has been and remains fixed on the Caribbean Islands, North America and most certainly Africa. This tendency is justifiable given the famous contributions of the many Pan-African freedom fighters and the formations hailing from these regions. But this has been at a cost. There remains significant portions of the African Diaspora whose place in and contributions to the advancement of Pan-Africanism has been glossed over or fully neglected. The subject of this paper is to introduce Belize as one of the neglected yet prolific fronts in the Pan-African phenomenon. Thus this essay utilizes a Pan- African nationalist theoretical framework that captures the place of Belize in the African Diaspora, with an emphasis on 1) identifying elements of Pan-Africanism based on a redefinition of the concept and 2) applying them in a way that illustrates the Pan-African tradition in Belize. -

Download PDF File

Friday, May 21, 2021 AMANDALABelize Page 1 NO. 3462 BELIZE CITY, FRIDAY, MAY 21, 2021 (36 PAGES) $1.50 Borders Gruesome daylight opened for city murder tourists only BELIZE CITY, Thurs. May of less than 24 hours. Last night, 20, 2021 Marquin Drury was fatally wounded At high noon today, a 19- in a drive-by shooting. year-old was shot multiple Unconfirmed reports are that times and left for dead in the Castillo was pursued by his assailant, Fabers Road Extension area. then executed in cold blood near a Stephan Castillo, the mechanic shop on Fabers Road, not victim of this most recent far from the police sub-station in that Belize City murder, is the area. second person to be shot to death in the city within a span Please turn toPage 29 Unions stage funeral procession for corruption BELIZE CITY, Wed. May 19, 2021 On Tuesday, May 18, members of the Belize National Teachers Union (BNTU) and the Public Service Union (PSU) staged mock funeral BELIZE CITY, Thurs. May 20, 2021 processions — a symbolic form of Today Cabinet released an update protest that is a marked departure on matters that were discussed and from the blockades that had been set decisions that were made during its up on the previous day to prevent the regular session meeting, which took flow of traffic on roads and highways place on May 18, 2021. In that press countrywide. They marched along the release, the public was informed that streets, carrying a coffin, as they pretended to engage in funeral rites Please turn toPage 30 Please turn toPage 31 PM replies PGIA employees Belize seeks extension to unions stage walkout for bond payment BELIZE CITY. -

UB-AR-2018-19.Pdf

This 2018-19 Annual Report is The University of Belize a publication of the Office of Belmopan Campus Marketing and Communications Hummingbird Avenue of the University of Belize. Belmopan, Cayo Vision & Mission Belize Editor in Chief +(501) 822-1000/822-3680 Professor Emeritus Clement K. Sankat www.ub.edu.bz Message from the Chairman _______________________ Author and Editor Ms. Santree Sandiford Business Campus President’s 2018-2019 Report Department of Marketing & University Drive Communications P.O. Box 990 Belize City, Belize UB at a Glance Author and Editor +(501) 223-2733 Ms. Sheena Zuniga Department of Marketing & Education Campus UB Strategic Plan 2017-2022 Communications University Drive P.O. Box 990 Graphic Designer Belize City, Belize Mrs. Zayri Cocom +(501) 223-0256 Teaching, Learning & the UB Experience Department of Marketing & Communications Central Farm Campus 65 Miles G.P. Hghwy Voices of Our Academic Leaders Cover Photo Image Cayo, Belize Rolando Cocom Photography +(501) 824 3775 UB Student Life Punta Gorda Campus Jose Maria Nunez St. Punta Gorda Town Toledo, Belize Research & Innovation +(501) 702 2720 For more information, please contact the Office at: Outreach & Engagements P: +(501) 822- 1000 ext. 202 E: [email protected] Organizational/Management Structure All rights reserved 2020 Financial Reporting “It always seems St. Augustine Campus, known as UB’s finances, precarious in the opportunities and deliver on the a savvy, intentional leader seeped best of times, were brought under current mantra - Reach, Relevance, impossible until it’s in years of UWI tradition leaves no management and the hitherto Responsiveness and Responsibility. stone unturned in his relentless done.” - Nelson Mandela quest for excellence. -

“We Are Strong Women”: a Focused Ethnography Of

“WE ARE STRONG WOMEN”: A FOCUSED ETHNOGRAPHY OF THE REPRODUCTIVE LIVES OF WOMEN IN BELIZE Carrie S. Klima, Ph.D. University of Connecticut, 2002 Belize is a small country in Central America with a unique heritage. The cultural pluralism found in Belize provides an opportunity to explore the cultures of the Maya, Mestizo and the Caribbean. Women in Belize share this cultural heritage as well as the reproductive health issues common to women throughout the developing world. The experiences of unintended pregnancy, contraceptive use and abortion were explored with women using a feminist ethnographic framework. Key informants, participant observations, secondary data sources and individual interviews provided rich sources of data to examine the impact of culture in Belize upon the reproductive lives of women. Data were collected over a two-year period and analyzed using QSRNudist qualitative data analysis software. Analysis revealed that regardless of age, ethnicity or educational background, women who found themselves pregnant prior to marriage experienced marriage as a fundamental cultural norm in Belize. Adolescent pregnancy often resulted in girls’ expulsion from school and an inability to continue with educational goals. Within marriage, unintended pregnancy was accepted but often resulted in more committed use of contraception. All women had some knowledge and experience with contraception, Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Carrie S. Klima-University of Connecticut, 2002 although some were more successful than others in planning their families. Couples usually made decisions together regarding when to use contraception, however misinformation regarding safety and efficacy was prevalent. While abortion is illegal, most women had knowledge of abortion practices and some had personal experiences with self induced abortions using traditional healing practices common in Belize. -

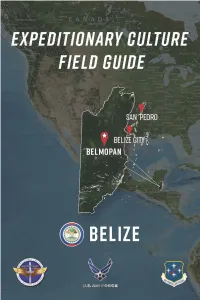

ECFG-Belize-2020R.Pdf

ECFG: Central America Central ECFG: About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: US Marine shows members of Belize Defense Force how to load ammunition into weapons). The guide consists of 2 E parts: CFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on Central America (CENTAM). Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Belize Belizean society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre- deployment training (Photo: USAF medic checks a Belizean patient’s vision during a medical readiness event). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

Download PDF File

Tuesday, April 13, 2021 AMANDALABelize Page 1 NO. 3451 BELIZE CITY, TUESDAY, APRIL 13, 2021 (20 PAGES) $1.00 PM Briceño presents lean budget “The National Budget is really a Budget about all the people — working people and business people 55 schools -– because from its birth to its burial, the National Budget touches all Belizeans in some way or the reopened other.” — Prime Minister Briceño BELMOPAN, Mon. Apr. 12, 2021 Representatives. His budget, titled On Friday, the Draft Estimates of “Today’s Sacrifice: Tomorrow’s Revenues and Expenditure for the Triumph!” outlined his government’s Fiscal Year 2021-2022 was goals to address the economic crisis presented by Prime Minister John Briceño. The PM delivered the Please turn toPage 19 national budget using a teleprompter, a first for the House of UDP discontinues UDP walks out after Julius claim against calls Patrick “boy” Mayor Wagner BELIZE CITY, Mon. Apr. 12, 2021 In late March, Cabinet approved the phased reopening of schools across the country, starting Monday, April 12, 2021. A memo issued by the CEO in the Ministry of Education announced that schools would be opened in two BELIZE CITY, Mon. Apr. 12, 2021 groups, with the first group reopening BELMOPAN, Fri. Apr. 9, 2021 the House of Representatives meeting The United Democratic Party has their classrooms on April 12. It has The Leader of the Opposition, at which this year’s budget was decided to withdraw its Supreme been one year since schools shuttered Hon. Patrick Faber, staged an opposition walkout on Friday from Please turn toPage 18 Please turn toPage 19 Please turn toPage 4 Siblings hit by truck, 11-year-old girl dies MOHW investigating post- vaccination death by Dayne Guy SANTA FAMILIA, Cayo, (See story on page 2) Mon. -

Coldblooded Murder in Santa Elena Sat

Tuesday, April 27, 2021 AMANDALABelize Page 1 BELIZE CITY, TUESDAY, APRIL 27, 2021 (20 PAGES) $1.00 T NO. 3455eachers str ike “…tell them to come to the table, bring some concrete solutions to the issues that we are having right now. Come to us seriously, bring the draft to us, and then we can talk,” Elena Smith, the BNTU’s national president, said. BELIZE CITY, Mon. Apr. 26, 2021 Today marked the first day of strike Deputy PM Hyde action by the Belize National Teachers Union (BNTU). Teachers beseeches unions countrywide staged a walkout from classes at 11:30 a.m. today, just after “It’s better for us to do something delivering the morning lessons. They now and find out a year from now later gathered at the Marion Jones that maybe we went too far, than Sports Complex, where they began a for us to not do anything and six cavalcade through the streets of months down the road we rue the Belize City. day we never took the 10%.” The union members walked in Deputy PM Hyde warned. Please turn toPage 19 Unions punta on Independence Hill NTUCB stands Elena Smith, national President of the BNTU, broke into dance in front of the with Joint Unions National Assembly Building as budget debates continued for a second day. The NTUCB release urged GOB to enact 9 good governance reforms BELIZE CITY. Mon. Apr. 26, 2021 Late this evening the National Trade Union Congress of Belize issued a release calling on the Government of Belize and Joint BELMOPAN, Fri. -

Domestic Violence and the Implications For

ABSTRACT WITHIN AND BEYOND THE SCHOOL WALLS: DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AND THE IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOLING by Elizabeth Joan Cardenas Domestic violence complemented by gendered inequalities impact both women and children. Research shows that although domestic violence is a global, prevalent social phenomenon which transcends class, race, and educational levels, this social monster and its impact have been relatively ignored in the realm of schooling. In this study, I problematize the issue of domestic violence by interrogating: How do the family and folk culture educate/miseducate children and adults about their gendered roles and responsibilities? How do schools reinforce the education/miseducation of these gendered roles and responsibilities? What can we learn about the effects of this education/ miseducation? What can schools do differently to bridge the gap between children and families who are exposed to domestic violence? This study introduces CAREPraxis as a possible framework for schools to implement an emancipatory reform. CAREPraxis calls for a re/definition of school leadership, home-school relationship, community involvement, and curriculum in order to improve the deficiency of relationality and criticality skills identified from the data sources on the issue of domestic violence. This study is etiological as well as political and is grounded in critical theory, particularly postcolonial theory and black women’s discourses, to explore the themes of representation, power, resistance, agency and identity. I interviewed six women, between ages 20 and 50, who were living or have lived in abusive relationships for two or more years. The two major questions asked were: What was it like when you were growing up? What have been your experiences with your intimate male partner with whom you live/lived. -

Land Loss and Garifuna Women's Activism on Honduras' North Coast

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 9 | Issue 1 Article 6 Sep-2007 Land Loss and Garifuna Women’s Activism on Honduras’ North Coast Keri Vacanti Brondo Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Brondo, Keri Vacanti (2007). Land Loss and Garifuna Women’s Activism on Honduras’ North Coast. Journal of International Women's Studies, 9(1), 99-116. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol9/iss1/6 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2007 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Land Loss and Garifuna Women’s Activism on Honduras’ North Coast By Keri Vacanti Brondo1 Abstract2 This paper reports on the gendered impacts of Honduras’ neoliberal agrarian legislation within the context of tourism development. It draws on ethnographic research with the Afro-indigenous Garifuna to demonstrate how women have been most affected by land privatization on the north coast of Honduras. Garifuna communities are matrifocal and land had historically been passed through matrilineal lines. As the coastal land market expands, Garifuna women have lost their territorial control. The paper also treats Garifuna women’s activism as they resist coastal development strategies and shifts in landholding. While women have been key figures in the Garifuna movement to title and reclaim lost ancestral land, the movement as a whole has yet to make explicit the gendered dimensions of the land struggle.