A Journal of African Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Writing the History of Southern Mesopotamia* by Eva Von

On Writing the History of Southern Mesopotamia* by Eva von Dassow — Colorado State University In his book Babylonia 689-627 B.C., G. Frame provides a maximally detailed his- tory of a specific region during a closely delimited time period, based on all available sources produced during that period or bearing on it. This review article critiques the methods used to derive the history from the sources and the conceptual framework used to apprehend the subject of the history. Babylonia 689-627 B. C , the revised version of Grant Frame's doc- toral dissertation, covers one of the most turbulent and exciting periods of Babylonian history, a time during which Babylon succes- sively experienced destruction and revival at Assyria's hands, then suf- fered rebellion and siege, and lastly awaited the opportunity to over- throw Assyria and inherit most of Assyria's empire. Although, as usual, the preserved textual sources cover these years unevenly, and often are insufficiently varied in type and origin (e.g., royal or non- royal, Babylonian or Assyrian), the years from Sennacherib's destruc- tion of Babylon in 689 to the eve of Nabopolassar's accession in 626 are also a richly documented period. Frame's work is an attempt to digest all of the available sources, including archaeological evidence as well as texts, in order to produce a maximally detailed history. Sur- rounding the book's core, chapters 5-9, which proceed reign by reign through this history, are chapters focussing on the sources (ch. 2), chronology (ch. 3), the composition of Babylonia's population (ch. -

Iranian Languages in the Persian Achamenid

ANALYZING INTER-VOLATILITY STRUCTURE TO DETERMINE OPTIMUM HEDGING RATIO FOR THE JET PJAEE, 18 (4) (2021) FUEL The Function of Non- Iranian Languages in the Persian Achamenid Empire Hassan Kohansal Vajargah Assistant professor of the University of Guilan-Rasht -Iran Email: hkohansal7 @ yahoo.com Hassan Kohansal Vajargah: The Function of Non- Iranian Languages in the Persian Achamenid Empire -- Palarch’s Journal Of Archaeology Of Egypt/Egyptology 18(4). ISSN 1567-214x Keywords: The Achamenid Empire, Non-Iranian languages, Aramaic language, Elamite language, Akkedi language, Egyptian language. ABSTRACT In the Achaemenid Empire( 331-559 B.C.)there were different tribes with various cultures. Each of these tribes spoke their own language(s). They mainly included Iranian and non- Iranian languages. The process of changes in the Persian language can be divided into three periods, namely , Ancient , Middle, and Modern Persian. The Iranian languages in ancient times ( from the beginning of of the Achaemenids to the end of the Empire) included :Median,Sekaee,Avestan,and Ancient Persian. At the time of the Achaemenids ,Ancient Persian was the language spoken in Pars state and the South Western part of Iran.Documents show that this language was not used in political and state affairs. The only remnants of this language are the slates and inscriptions of the Achaemenid Kings. These works are carved on stone, mud,silver and golden slates. They can also be found on coins,seals,rings,weights and plates.The written form of this language is exclusively found in inscriptions. In fact ,this language was used to record the great and glorious achivements of the Achaemenid kings. -

Considering the Failures of the Parthians Against the Invasions of the Central Asian Tribal Confederations in the 120S Bce

NIKOLAUS OVERTOOM WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY CONSIDERING THE FAILURES OF THE PARTHIANS AGAINST THE INVASIONS OF THE CENTRAL ASIAN TRIBAL CONFEDERATIONS IN THE 120S BCE SUMMARY When the Parthians rebelled against the Seleucid Empire in the middle third century BCE, seizing a large section of northeastern Iran, they inherited the challenging responsibility of monitoring the extensive frontier between the Iranian plateau and the Central Asian steppe. Although initially able to maintain working relations with various tribal confederations in the region, with the final collapse of the Bactrian kingdom in the 130s BCE, the ever-wide- ning eastern frontier of the Parthian state became increasingly unstable, and in the 120s BCE nomadic warriors devastated the vulnerable eastern territories of the Parthian state, temporarily eliminating Parthian control of the Iranian plateau. This article is a conside- ration of the failures of the Parthians to meet and overcome the obstacles they faced along their eastern frontier in the 120s BCE and a reevaluation of the causes and consequences of the events. It concludes that western distractions and the mismanagement of eastern affairs by the Arsacids turned a minor dispute into one of the most costly and difficult struggles in Parthian history. Key-words: history; Parthians; Seleucids; Central Asia; nomads; frontiers. RÉSUMÉ Lorsque, au milieu du IIIe siècle av. J.-C., les Parthes se rebellèrent contre l’État séleucide en s’emparant d’une grande partie du nord-est de l’Iran, ils héritèrent de la tâche difficile -

SUMERIAN LITERATURE and SUMERIAN IDENTITY My Title Puts

CNI Publicati ons 43 SUMERIAN LITERATURE AND SUMERIAN IDENTITY JERROLD S. COOPER PROBLEMS OF C..\NONlCl'TY AND IDENTITY FORMATION IN A NCIENT EGYPT AND MESOPOTAMIA There is evidence of a regional identity in early Babylonia, but it does not seem to be of the Sumerian ethno-lingusitic sort. Sumerian Edited by identity as such appears only as an artifact of the scribal literary KIM RYHOLT curriculum once the Sumerian language had to be acquired through GOJKO B AR .I AMOVIC educati on rather than as a mother tongue. By the late second millennium, it appears there was no notion that a separate Sumerian ethno-lingui stic population had ever existed. My title puts Sumerian literature before Sumerian identity, and in so doing anticipates my conclusion, which will be that there was little or no Sumerian identity as such - in the sense of "We are all Sumerians!" outside of Sumerian literature and the scribal milieu that composed and transmitted it. By "Sumerian literature," I mean the corpus of compositions in Sumerian known from manuscripts that date primarily 1 to the first half of the 18 h century BC. With a few notable exceptions, the compositions themselves originated in the preceding three centuries, that is, in what Assyriologists call the Ur III and Isin-Larsa (or Early Old Babylonian) periods. I purposely eschew the too fraught and contested term "canon," preferring the very neutral "corpus" instead, while recognizing that because nearly all of our manuscripts were produced by students, the term "curriculum" is apt as well. 1 The geographic designation "Babylonia" is used here for the region to the south of present day Baghdad, the territory the ancients would have called "Sumer and Akkad." I will argue that there is indeed evidence for a 3rd millennium pan-Babylonian regional identity, but little or no evidence that it was bound to a Sumerian mother-tongue community. -

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

The Limits of Middle Babylonian Archives1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenstarTs The Limits of Middle Babylonian Archives1 susanne paulus Middle Babylonian Archives Archives and archival records are one of the most important sources for the un- derstanding of the Babylonian culture.2 The definition of “archive” used for this article is the one proposed by Pedersén: «The term “archive” here, as in some other studies, refers to a collection of texts, each text documenting a message or a statement, for example, letters, legal, economic, and administrative documents. In an archive there is usually just one copy of each text, although occasionally a few copies may exist.»3 The aim of this article is to provide an overview of the archives of the Middle Babylonian Period (ca. 1500-1000 BC),4 which are often 1 All kudurrus are quoted according to Paulus 2012a. For a quick reference on the texts see the list of kudurrus in table 1. 2 For an introduction into Babylonian archives see Veenhof 1986b; for an overview of differ- ent archives of different periods see Veenhof 1986a and Brosius 2003a. 3 Pedersén 1998; problems connected to this definition are shown by Brosius 2003b, 4-13. 4 This includes the time of the Kassite dynasty (ca. 1499-1150) and the following Isin-II-pe- riod (ca. 1157-1026). All following dates are BC, the chronology follows – willingly ignoring all linked problems – Gasche et. al. 1998. the limits of middle babylonian archives 87 left out in general studies,5 highlighting changes in respect to the preceding Old Babylonian period and problems linked with the material. -

On the Western Edge of the Iranian Plateau: Susa and El Ymais

CHAPTER THREE ON THE WESTERN EDGE OF THE IRANIAN PLATEAU: SUSA AND EL YMAIS Susa Refounded by Seleucus as a Greek polis under the name Seleucia-on-the-Eulaeus 1, Susa was never to regain its former rank of imperial capital; but down to the end of the Parthian period it remained an important city, the head of a satrapy whose bound aries corresponded-at least originally-to the present-day prbv ince of Khuzistan. Unlike Persepolis, it had not been deprived of its former royal splendour, and its palaces were maintained, with a veneer of Greek decoration, for the use of the Macedonian satrap and occasional visits by the Seleucid court2; an inscription datable to the end of the third century B.C. mentions "Timon, the chief of the royal palace" 3• As a military stronghold Susa kept a great strategic importance; in 222 Molon, the rebellious satrap of Media, occupied the lower town ( the " craftsmen's town" of the archaeolo gists), but was unable to capture the upper town.4 Susa continued to play a major economic role, the tributes brought from all parts of the Persian empire being now replaced by a trade conducted by merchants, predominantly along the Mesopo tamian axis. It has even been argued that the Seleucid kings deliberately favoured this development, the new foundation of Susa going together with the creation of a direct waterway between the 1 The fundamental work on Susa during this (and the subsequent) period is Le Rider, Suse, 1965. (Tarn, GBI, 27, considers that Seleucia-on-the-Eulaeus was first founded as a military colony, and became a polis only under Antiochus III; but see Le Rider, o.c., pp. -

An Analytical Study on 12 Coins from Elymais Era Recovered at Tang-E

Vol. 2, No. 4, Summer- Autumn 2016 International Journal of the Society of Iranian Archaeologists An Analytical Study on 12 Coins from Elymais Era Recovered at Tang-e Sulak Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad Province, Southwestern Iran, through Particle Induced X-Ray Spectroscopy (PIXE) Ali Aarab University of Tehran Soraya Estavi Mohaghegh Ardebili University Parvin Oliaiy Atomic Energy Organization of Iran Narges Asadpuor Islamic Azad University Received: May, 30, 2016 Accepted: September, 12, 2016 Abstract: Elymais is known as a semi-autonomous state which ruled during the Parthian period. They can be considered as a successor to the Elamite power throughout the history of Persia. Located in the southwest of Iran, Tang-e Sulak is one of the important regions where numerous Elymaisian artifacts have been discovered. In this research 12 copper coins recovered at Tang-e Sulak are examined. According to previous studies on these coins, there are evident signs of economic and political chaos from the Elymais Era. Moreover, the proportion of elements in these coins obtained from spectroscopy can argue there are at least two different mines involved. Meanwhile, this study discussed the technology by which copper was isolated from its ore over the Elymais Era. In that light, a good insight can be gained about the great importance of Particle Induced X-Ray Spectroscopy (PIXE) in archaeological studies and relevant analyses in the Elymais Era. Keywords: Elymais, Tang-e Sulak, PIXE spectroscopy, metal mines. Introduction Given the insufficient data about the regions where Elymais i.e. Susiana (Weissbach 1905: 24-58). In fact, the Elymais people inhabited, it is crucial to investigate Elymais coins. -

The Neo-Babylonian Empire New Babylonia Emerged out of the Chaos That Engulfed the Assyrian Empire After the Death of the Akka

NAME: DATE: The Neo-Babylonian Empire New Babylonia emerged out of the chaos that engulfed the Assyrian Empire after the death of the Akkadian king, Ashurbanipal. The Neo-Babylonian Empire extended across Mesopotamia. At its height, the region ruled by the Neo-Babylonian kings reached north into Anatolia, east into Persia, south into Arabia, and west into the Sinai Peninsula. It encompassed the Fertile Crescent and the Tigris and Euphrates River valleys. New Babylonia was a time of great cultural activity. Art and architecture flourished, particularly under the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II, was determined to rebuild the city of Babylonia. His civil engineers built temples, processional roadways, canals, and irrigation works. Nebuchadnezzar II sought to make the city a testament not only to Babylonian greatness, but also to honor the Babylonian gods, including Marduk, chief among the gods. This cultural revival also aimed to glorify Babylonia’s ancient Mesopotamian heritage. During Assyrian rule, Akkadian language had largely been replaced by Aramaic. The Neo-Babylonians sought to revive Akkadian as well as Sumerian-Akkadian cuneiform. Though Aramaic remained common in spoken usage, Akkadian regained its status as the official language for politics and religious as well as among the arts. The Sumerian-Akkadian language, cuneiform script and artwork were resurrected, preserved, and adapted to contemporary uses. ©PBS LearningMedia, 2015 All rights reserved. Timeline of the Neo-Babylonian Empire 616 Nabopolassar unites 575 region as Neo- Ishtar Gate 561 Amel-Marduk becomes king. Babylonian Empire and Walls of 559 Nerglissar becomes king. under Babylon built. 556 Labashi-Marduk becomes king. Chaldean Dynasty. -

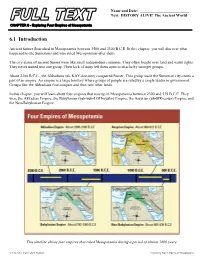

Text: HISTORY ALIVE! the Ancient World

Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Ancient World 6.1 Introduction Ancient Sumer flourished in Mesopotamia between 3500 and 2300 B.C.E. In this chapter, you will discover what happened to the Sumerians and who ruled Mesopotamia after them. The city-states of ancient Sumer were like small independent countries. They often fought over land and water rights. They never united into one group. Their lack of unity left them open to attacks by stronger groups. About 2300 B.C.E., the Akkadians (uh-KAY-dee-unz) conquered Sumer. This group made the Sumerian city-states a part of an empire. An empire is a large territory where groups of people are ruled by a single leader or government. Groups like the Akkadians first conquer and then rule other lands. In this chapter, you will learn about four empires that rose up in Mesopotamia between 2300 and 539 B.C.E. They were the Akkadian Empire, the Babylonian (bah-buh-LOH-nyuhn) Empire, the Assyrian (uh-SIR-ee-un) Empire, and the Neo-Babylonian Empire. This timeline shows four empires that ruled Mesopotamia during a period of almost 1800 years. © Teachers’ Curriculum Institute Exploring Four Empires of Mesopotamia Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Ancient World 6.2 The Akkadian Empire For 1,200 years, Sumer was a land of independent city-states. Then, around 2300 B.C.E., the Akkadians conquered the land. The Akkadians came from northern Mesopotamia. They were led by a great king named Sargon. Sargon became the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire. -

From Small States to Universalism in the Pre-Islamic Near East

REVOLUTIONIZING REVOLUTIONIZING Mark Altaweel and Andrea Squitieri and Andrea Mark Altaweel From Small States to Universalism in the Pre-Islamic Near East This book investigates the long-term continuity of large-scale states and empires, and its effect on the Near East’s social fabric, including the fundamental changes that occurred to major social institutions. Its geographical coverage spans, from east to west, modern- day Libya and Egypt to Central Asia, and from north to south, Anatolia to southern Arabia, incorporating modern-day Oman and Yemen. Its temporal coverage spans from the late eighth century BCE to the seventh century CE during the rise of Islam and collapse of the Sasanian Empire. The authors argue that the persistence of large states and empires starting in the eighth/ seventh centuries BCE, which continued for many centuries, led to new socio-political structures and institutions emerging in the Near East. The primary processes that enabled this emergence were large-scale and long-distance movements, or population migrations. These patterns of social developments are analysed under different aspects: settlement patterns, urban structure, material culture, trade, governance, language spread and religion, all pointing at population movement as the main catalyst for social change. This book’s argument Mark Altaweel is framed within a larger theoretical framework termed as ‘universalism’, a theory that explains WORLD A many of the social transformations that happened to societies in the Near East, starting from Andrea Squitieri the Neo-Assyrian period and continuing for centuries. Among other infl uences, the effects of these transformations are today manifested in modern languages, concepts of government, universal religions and monetized and globalized economies.