Residential Financ Ng N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography-Of-Texas-Speleology

1. Anonymous. n.d. University of Texas Bulletin No. 4631, pp. 51. 2. Anonymous. 1992. Article on Pendejo Cave. Washington Post, 10 February 1992. 3. Anonymous. 1992. Article on bats. Science News, 8 February 1992. 4. Anonymous. 2000. National Geographic, 2000 (December). 5. Anonymous. n.d. Believe odd Texas caves is Confederate mine; big rock door may be clue to mystery. 6. Anonymous. n.d. The big dig. Fault Zone, 4:8. 7. Anonymous. n.d. Cannibals roam Texas cave. Georgetown (?). 8. Anonymous. n.d. Cavern under highway is plugged by road crew. Source unknown. 9. Anonymous. n.d. Caverns of Sonora: Better Interiors. Olde Mill Publ. Co., West Texas Educators Credit Union. 10. Anonymous. n.d. Crawling, swimming spelunkers discover new rooms of cave. Austin(?). Source unknown. 11. Anonymous. n.d. Discovery (of a sort) in Airmen's Cave. Fault Zone, 5:16. 12. Anonymous. n.d. Footnotes. Fault Zone, 5:13. 13. Anonymous. n.d. Help the blind... that is, the Texas blind salamander [Brochure]: Texas Nature Conservancy. 2 pp. 14. Anonymous. n.d. Honey Creek map. Fault Zone, 4:2. 15. Anonymous. n.d. The Langtry mini-project. Fault Zone, 5:3-5. 16. Anonymous. n.d. Neuville or Gunnels Cave. http:// www.shelbycountytexashistory.org/neuvillecave.htm [accessed 9 May 2008]. 17. Anonymous. n.d. Palo Duro Canyon State Scenic Park. Austin: Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. 2 pp. 18. Anonymous. n.d. Texas blind salamander (Typhlomolge rathbuni). Mississippi Underground Dispatch, 3(9):8. 19. Anonymous. n.d. The TSA at Cascade Caverns. Fault Zone, 4:1-3, 7-8. -

Community Service Worksheet

Place Code Site Name Address Hours of Operation Contact Person Phone # Westside CS116 Franklin Mountains State Park Transmountain Mon-Sun 8:00am to 5:00pm Robert Pichardo/Raul Gomez 566-6441 79912 MALES ONLY & Erika Rubio Westside CS127 Galatzan Rec Center 650 Wallenberg Dr. Mon - Th 1pm to 9pm; Friday 1pm to Carlos Apodaca Robert 581-5182 79912 6pm; Saturday 9am to 2pm Owens Westside CS27 Don Haskins Rec Center 7400 High Ridge Fridays 2:00pm to 6:00pm Rick Armendariz 587-1623 79912 Saturdays 9:00am to 2:00pm Westside CS140 Rescue Mission 1949 W. Paisano Residents Only Staff 532-2575 79922 Westside CS101 Environmental Services (West) 121 Atlantic Tue-Sat 8:00am to 4:00pm Jose Flores 873-8633 Martin Sandiego/Main Supervisor 472-4844 79922 Westside CS142 Westside Regional Command 4801 Osborne Drive Wed 7:00am-10:00am Orlando Hernandez 585-6088 79922 Canutillo CS111 Canutillo County Nutrition 7361 Bosque Mon-Fri 9:00am to 1:00pm Irma Torres 877-2622 (close to Westside) 79835 Canutillo CS117 St. Vincent De Paul Thrift Store 6950 3rd Street Tues-Sat 10:00am to 6:00pm Mari Cruz P. Lee 877-7030 (W) 79835 Vinton CS143 Westside Field Office 435 Vinton Rd Mon-Fri 8:00am to 6:00pm. Support Staff 886-1040 79821 Vinton CS67 Village of Vinton-(close to 436 E. Vinton Mon-Fri 8:00am to 4:00pm Perch Valdez, José Alarcón 383-6993 Anthony) avail for light duty- No 79821 Central- CS53 Chihuahuita Community Center 417 Charles Road Mon - Fri 11:00am to 6:00pm Patricia Rios 533-6909 DT 79901 Central- CS11 Civic Center Maintenance #1 Civic Center Plaza Mon-Fri 6:00am to 4:00pm Manny Molina 534-0626/ DT 79901 534-0644 Central- CS14 Opportunity Center 1208 Myrtle Mon-Fri 6:00am to 6:00p.m. -

FRIENDS of THC BOARD of DIRECTORS Name Address City State Zip Work Home Mobile Email Email Code Killis P

FRIENDS OF THC BOARD OF DIRECTORS Name Address City State Zip Work Home Mobile Email Email Code Killis P. Almond 342 Wilkens San TX 78210 210-532-3212 512-532-3212 [email protected] Avenue Antonio Peggy Cope Bailey 3023 Chevy Houston TX 77019 713-523-4552 713-301-7846 [email protected] Chase Drive Jane Barnhill 4800 Old Brenham TX 77833 979-836-6717 [email protected] Chappell Hill Road Jan Felts Bullock 3001 Gilbert Austin TX 78703 512-499-0624 512-970-5719 [email protected] Street Diane D. Bumpas 5306 Surrey Dallas TX 75209 214-350-1582 [email protected] Circle Lareatha H. Clay 1411 Pecos Dallas TX 75204 214-914-8137 [email protected] [email protected] Street Dianne Duncan Tucker 2199 Troon Houston TX 77019 713-524-5298 713-824-6708 [email protected] Road Sarita Hixon 3412 Houston TX 77027 713-622-9024 713-805-1697 [email protected] Meadowlake Lane Lewis A. Jones 601 Clark Cove Buda TX 78610 512-312-2872 512-657-3120 [email protected] Harriet Latimer 9 Bash Place Houston TX 77027 713-526-5397 [email protected] John Mayfield 3824 Avenue F Austin TX 78751 512-322-9207 512-482-0509 512-750-6448 [email protected] Lynn McBee 3912 Miramar Dallas TX 75205 214-707-7065 [email protected] [email protected] Avenue Bonnie McKee P.O. Box 120 Saint Jo TX 76265 940-995-2349 214-803-6635 [email protected] John L. Nau P.O. Box 2743 Houston TX 77252 713-855-6330 [email protected] [email protected] Virginia S. -

ROCK PAINTINGS at HUECO TANKS STATE HISTORIC SITE by Kay Sutherland, Ph.D

PWD BK P4501-095E Hueco 6/22/06 9:06 AM Page A ROCK PAINTINGS AT HUECO TANKS STATE HISTORIC SITE by Kay Sutherland, Ph.D. PWD BK P4501-095E Hueco 6/22/06 9:06 AM Page B Mescalero Apache design, circa 1800 A.D., part of a rock painting depicting white dancing figures. Unless otherwise indicated, the illustrations are photographs of watercolors by Forrest Kirkland, reproduced courtesy of Texas Memorial Museum. The watercolors were photographed by Rod Florence. Editor: Georg Zappler Art Direction: Pris Martin PWD BK P4501-095E Hueco 6/22/06 9:06 AM Page C ROCK PAINTINGS AT HUECO TANKS STATE HISTORIC SITE by Kay Sutherland, Ph.D. Watercolors by Forrest Kirkland Dedicated to Forrest and Lula Kirkland PWD BK P4501-095E Hueco 6/22/06 9:06 AM Page 1 INTRODUCTION The rock paintings at Hueco Tanks the “Jornada Mogollon”) lived in State Historic Site are the impres- small villages or pueblos at and sive artistic legacy of the different near Hueco Tanks and painted on prehistoric peoples who found the rock-shelter walls. Still later, water, shelter and food at this the Mescalero Apaches and possibly stone oasis in the desert. Over other Plains Indian groups 3000 paintings depict religious painted pictures of their rituals masks, caricature faces, complex and depicted their contact with geometric designs, dancing figures, Spaniards, Mexicans and Anglos. people with elaborate headdresses, The European newcomers and birds, jaguars, deer and symbols settlers left no pictures, but some of rain, lightning and corn. Hidden chose instead to record their within shelters, crevices and caves names with dates on the rock among the three massive outcrops walls, perhaps as a sign of the of boulders found in the park, the importance of the individual in art work is rich in symbolism and western cultures. -

A Preliminary Assessment of the Geologic Setting, Hydrology, and Geochemistry of the Hueco Tanks Geothermal Area, Texas and New Mexico

Geological Circular 81-1 APreliminaryAssessmentoftheGeologicSetting,Hydrology,andGeochemistyoftheHuecoTanksGeothermalArea,TexasandNewMexico Christopher D.Henry and James K.Gluck jointly published by Bureau of Economic Geology The University of Texas at Austin Austin, Texas 78712 W. L.Fisher,Director and Texas Energy and Natural Resources Advisory Council Executive Office Building 411 West 13th Street, Suite 800 Austin, Texas 78701 Milton L. Holloway, Executive Director prime funding provided by Texas Energy and Natural Resources Advisory Council throughInteragency Cooperation Contract No.IAC(80-81)-0899 1981 Contents Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Regional geologic setting 2 Origin and locationof geothermal waters 5 Hot wells 5 Source of heat and ground-water flow paths 5 Faults in geothermal area 9 Implications of geophysical data 15 Hydrology 16 Data availability 16 Water-table elevation 17 Substrate permeability 19 Geochemistry 22 Geothermometry 27 Summary 32 Acknowledgments 32 References 33 Appendix A. Well data 35 Appendix B. Chemical analyses Wl Appendix C. Well designations WJ Figures 1. Tectonic map of Hueco Bolson near El Paso, Texas 3 2. Wells in Hueco Tanks geothermal area 6 3. Measured andreported temperatures ( C) of thermal and nonthermal wells 7 4. Depth to bedrock, absolute elevation of bedrock, and inferred normal faults . 10 5. Generalized west-east cross sections in Hueco Tanks geothermal area . .11 6. Depth to water table, absolute elevation of water table, and water- table elevation contours 18 111 7. Percentages of gravel, sand, clay, and bedrock from driller's logs 21 8. Trilinear diagram of thermal and nonthermal waters 24 9. Total dissolved solids and chloride concentrations 25 Tables 1. Saturation indices 28 2. -

BIRDS of the TRANS-PECOS a Field Checklist

TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE BIRDS of the TRANS-PECOS a field checklist Black-throated Sparrow by Kelly B. Bryan Birds of the Trans-Pecos: a field checklist the chihuahuan desert Traditionally thought of as a treeless desert wasteland, a land of nothing more than cacti, tumbleweeds, jackrabbits and rattlesnakes – West Texas is far from it. The Chihuahuan Desert region of the state, better known as the Trans-Pecos of Texas (Fig. 1), is arguably the most diverse region in Texas. A variety of habitats ranging from, but not limited to, sanddunes, desert-scrub, arid canyons, oak-juniper woodlands, lush riparian woodlands, plateau grasslands, cienegas (desert springs), pinyon-juniper woodlands, pine-oak woodlands and montane evergreen forests contribute to a diverse and complex avifauna. As much as any other factor, elevation influences and dictates habitat and thus, bird occurrence. Elevations range from the highest point in Texas at 8,749 ft. (Guadalupe Peak) to under 1,000 ft. (below Del Rio). Amazingly, 106 peaks in the region are over 7,000 ft. in elevation; 20 are over 8,000 ft. high. These montane islands contain some of the most unique components of Texas’ avifauna. As a rule, human population in the region is relatively low and habitat quality remains good to excellent; habitat types that have been altered the most in modern times include riparian corridors and cienegas. Figure 1: Coverage area is indicated by the shaded area. This checklist covers all of the area west of the Pecos River and a corridor to the east of the Pecos River that contains areas of Chihuahuan Desert habitat types. -

El Paso Del Norte: a Cultural Landscape History of the Oñate Crossing on the Camino Real De Tierra Adentro 1598 –1983, Ciudad Juárez and El Paso , Texas, U.S.A

El Paso del Norte: A Cultural Landscape History of the Oñate Crossing on the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro 1598 –1983, Ciudad Juárez and El Paso , Texas, U.S.A. By Rachel Feit, Heather Stettler and Cherise Bell Principal Investigators: Deborah Dobson-Brown and Rachel Feit Prepared for the National Park Service- National Trails Intermountain Region Contract GS10F0326N August 2018 EL PASO DEL NORTE: A CULTURAL LANDSCAPE HISTORY OF THE OÑATE CROSSING ON THE CAMINO REAL DE TIERRA ADENTRO 1598–1893, CIUDAD JUÁREZ, MEXICO AND EL PASO, TEXAS U.S.A. by Rachel Feit, Heather Stettler, and Cherise Bell Principal Investigators: Deborah Dobson-Brown and Rachel Feit Draft by Austin, Texas AUGUST 2018 © 2018 by AmaTerra Environmental, Inc. 4009 Banister Lane, Suite 300 Austin, Texas 78704 Technical Report No. 247 AmaTerra Project No. 064-009 Cover photo: Hart’s Mill ca. 1854 (source: El Paso Community Foundation) and Leon Trousset Painting of Ciudad Juárez looking toward El Paso (source: The Trousset Family Online 2017) Table of Contents Table of Contents Chapter 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro ....................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The Oñate Crossing in Context .............................................................................................................. 1 ..................................................................... -

Download The

-Official- FACILITIES MAPS ACTIVITIES Get the Mobile App: texasstateparks.org/app T:10.75" T:8.375" Toyota Tundra Let your sense of adventure be your guide with the Toyota BUILT HERE. LIVES HERE. ASSEMBLED IN TEXAS WITH U.S. AND GLOBALLY SOURCED PARTS. Official Vehicle of Tundra — built to help you explore all that the great state the Texas Parks & Wildlife Foundation of Texas has to offer. | toyota.com/trucks F:5.375" F:5.375" Approvals GSTP20041_TPW_State_Park_Guide_Trucks_CampOut_10-875x8-375. Internal Print None CD Saved at 3-4-2020 7:30 PM Studio Artist Rachel Mcentee InDesign 2020 15.0.2 AD Job info Specs Images & Inks Job GSTP200041 Live 10.375" x 8" Images Client Gulf States Toyota Trim 10.75" x 8.375" GSTP20041_TPW_State_Park_Guide_Ad_Trucks_CampOut_Spread_10-75x8-375_v4_4C.tif (CMYK; CW Description TPW State Park Guide "Camp Out" Bleed 11.25" x 8.875" 300 ppi; 100%), toyota_logo_vert_us_White_cmyk.eps (7.12%), TPWF Logo_2015_4C.EPS (10.23%), TPWF_WWNBT_Logo_and_Map_White_CMYK.eps (5.3%), GoTexan_Logo_KO.eps (13.94%), Built_Here_ Component Spread Print Ad Gutter 0.25" Lives_Here.eps (6.43%) Pub TPW State Park Guide Job Colors 4CP Inks AE Media Type Print Ad Production Notes Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black Date Due 3/5/2020 File Type Due PDFx1a PP Retouching N/A Add’l Info TM T:10.75" T:8.375" Toyota Tundra Let your sense of adventure be your guide with the Toyota BUILT HERE. LIVES HERE. ASSEMBLED IN TEXAS WITH U.S. AND GLOBALLY SOURCED PARTS. Official Vehicle of Tundra — built to help you explore all that the great state the Texas Parks & Wildlife Foundation of Texas has to offer. -

Sustaining a Viable State Parks System Operations and Infrastructure

Sustaining a Viable State Parks System Operations and Infrastructure Recommendations of the 1 Texas State Park Advisory Committee 2 3 4 Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 6 Key Recommendations ............................................................................................................................. 6 Texas State Parks are Smart Government ................................................................................................ 7 Challenges of Texas State Parks ............................................................................................................... 7 The Texas Legacy ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Goals of this Report .................................................................................................................................. 9 The Value of Texas State Parks ................................................................................................................. 9 State Parks as an Industry are Changing Nationally ............................................................................... 11 A Mismatch of Resources and Expectations.......................................................................................... -

West Texas Trip Itineraries

ITINERARIES 2016 FEATURING: ABILENE AMARILLO BIG BEND DENTON EL PASO FORT DAVIS FORT WORTH GRANBURY LUBBOCK MIDLAND ODESSA SAN ANGELO FOR THE TEXAS GROUP TOUR EXPERIENCE OF A LIFETIME WestTexasTrip.com • 1 WEST TEXAS TRIP ITINERARIES EXPERTLY CURATED TRAVEL ITINERARIES for groups of all sizes, across the wide-open spaces and authentic places of the Texas you’ve always dreamed of exploring COME EXPERIENCE THE SKIES AND SUNSETS, dramatic vistas, and fascinating heritage of West Texas. From vast plains and canyonlands to historic forts to the mountains and the Rio Grande, from small-town charm to city lights, from the old Butterfield Overland and Chisholm Trails to Route 66, there’s plenty for visitors to see and enjoy while touring by motor coach or other transport. And we’ve made the planning simple for you. OUR LOOP ITINERARIES link destinations and attractions by a variety of themes. Or if you prefer point-to-point travel, it’s easy to pick the segment that suits your needs, by city of arrival or departure, by land or by air. TOUR GROUPS are encouraged to combine these different loops, depending on interests and length of travel. And if you prefer, our participating local partners will be glad to design a custom itinerary for you. Select your theme and explore the color-coded loops for specifics. NEED A LOCAL GUIDE? We can help there, too. Experienced step-on guides, docents, and certified tourism professionals are available in most locations. Give us a shout. AND START PLANNING YOUR TRIP OF A LIFETIME. WWW.WESTTEXASTRIP.COM 2 • WestTexasTrip.com BEST OF WEST TEXAS ANNUAL EVENTS Use this handy calendar of our major events to plan your trip — and check your favorites along each color-coded loop. -

Family Field Trip Guide

Central Prairies & Cross Timbers Panhandle Piney Plains Woods Trans-Pecos Family Field Trip Hill Guide Country South Texas Gulf Coastal Plains Plains Copyright 2018 / Discover Texas History Wherever you live, there’s an adventure nearby! These field trip ideas will help you discover Texas History adventures near you. Panhandle Plains Fort Phantom Hill/Abilene Frontier Texas!/Abilene Fort Griffin State Historic Site/Albany Palo Duro Canyon State Park/Canyon Panhandle Plains Historical Museum/Canyon XIT Ranch Museum/Dalhart Charles Goodnight Historical Center/Goodnight Lake Lubbock Landmark/Lubbock The Science Spectrum (Brazos River Journey)/Lubbock National Ranching Heritage Center/Lubbock American Windmill Museum/Lubbock Devil’s Rope and Route 66 Museum/McLean Petroleum Museum/Midland Fort Belknap/Newcastle Fort Concho/San Angelo Copyright 2018 / Discover Texas History Central Prairies & Cross Timbers Fanthorp Inn State Historic Site/Anderson Sam Rayburn House State Historic Site/Bonham Blue Bell Creamery/Brenham Texas Cotton Gin Museum/Burton Eisenhower Birthplace/Denison Fort Worth Stockyards/Fort Worth Texas Civil War Museum/Fort Worth Creation Evidence Museum/Glen Rose Audie Murphy American Cotton Museum/Greenville Confederate Reunion Grounds State Historical Site/Mexia Sam Bell Maxey House State Historic Site/Paris San Felipe de Austin State Historic Site/San Felipe Waco Mammoth Site/Waco Dr Pepper Museum & Free Enterprise Institute/Waco Earle-Harrison House & Gardens/Waco Historic Waco Foundation (Five 19th century homes)/Waco Texas -

El Paso New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 2Q20

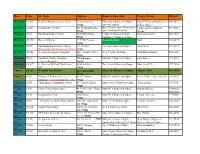

El Paso New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 2Q20 1 ID PROPERTY UNITS 1 The Flats at Ridgeview Phase II 96 Total Lease Up 96 5 Dwight D. Eisenhower Phase III 66 5 7 Villas at Augusta 120 22 8 Muralla Way 360 12 Hillary J. Sandoval, 12 Jr. Redevelopment 224 7 13 Edgemere Palms 96 18 Total Planned 866 13 18 Mountainview Estates 92 20 19 Vista Del Sol Estates 92 19 20 Zaragoza Place 128 22 Medano Heights Phase II 66 24 8 23 Eastlake Palms 124 24 Pellicano Palms 152 23 Total Prospective 654 5 mi Source: Yardi Matrix LEGEND Lease-Up Under Construction Planned Prospective El Paso New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects 2Q20 10 9 11 21 4 ID PROPERTY UNITS 2 Nuestra Senora 80 3 Sherman Plaza Phase III 50 6 4 Kathy White Memorial Redevelopment 72 6 The Gateway 100 16 9 201 Shadow Mountain 228 2 3 10 Montecillo Town Center 185 15 17 11 Robinson Redevelopment 184 14 Total Planned 899 14 Kansas Street & Mills Avenue 180 15 Sunset Bluff 50 16 Tays North Redevelopment 278 17 Valle Verde Renovations 50 21 9 West 76 Total Prospective 634 1 mi Source: Yardi Matrix LEGEND Lease-Up Under Construction Planned Prospective El Paso New Construction & Proposed Multifamily Projects PERMIT FORECASTED START OF ID PROPERTY NAME ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP STATUS UNITS SUBMARKET DATE COMPLETION DATE RENT-UP 1 The Flats at Ridgeview Phase II 2050 Wisconsin Avenue Las Cruces NM 88001 Lease-Up 96 Las Cruces - West 08/31/2019 07/31/2020 01/01/2020 Total Lease-Up 96 2 Nuestra Senora 405 Montana Avenue El Paso TX 79902 Planned 80 Central El Paso 3 Sherman Plaza Phase III 4258 Blanco Avenue El Paso TX 79905 Planned 50 Central El Paso Kathy White 4 Memorial Redevelopment 2500 Mobile Avenue El Paso TX 79930 Planned 72 North Central El Paso 5 Dwight D.