Sunset Advisory Commission Staff Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Residential Financ Ng N

Residential Financ ng n the Colonias Report To the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development By: Perspectiva ICF Consulting Bruce Ferguson January 30, 2004 I TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY IV II. INTRODUCTION,. 1 III. METHODOLOGY J 1. LTTERATURE REVTEW ...................... 3 2. DATA ANALYSIS 3 3. INTERVIEWS AND FOCUS GROUPS 4 IV. BACKGROUND ON COLONIAS 5 1. INTRODUCTION tr a. Definitional lssues: What is a Colonia? ..........5 b. Continuing Growth .......,..6 c. lnternational Context. ...,,,,..,7 2. COLONIAS:A CLOSER LOOK. ..........8 a. Texas Colonias ........'l 0 b. Arizona Colonias .,.,.,.,14 c. New [Vexico Colonias ...,...,17 d. California Colonias .,...,.,21 3. CONCLUS|ONS........ ........24 V. RESIDENTIAL FINANCE IN COLONIAS 25 1. OVERVIEW OF KEY EXISTING RESIDENTIAL FINANCE ISSUES 25 2. CHARACTERISTICS OF HOUSING FINANCE IN COLONIAS......... 26 a. Factors affecting access to conventional housing finance 28 b. Key points from focus groups and interviews.............. 30 3. CURRENT ESTIMATED LENDING ACTIVITY IN COLONIAS......... 33 a. Texas Colonias 33 b. Arizona Colonias 36 c. New Mexico Colonias 3B d. California Colonias 40 4. CONCLUSIONS.,...... 42 VI. INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES 44 1. OVERVIEW OF COLONIAS INTERNATIONALLY 44 a. Colonia Formation b. Colonias solve the individual's housing problem but at great public and private cost. ....46 c. Upgrading and/or slowing colonia formation requires a wide range of housing "solutions." ,.,,.,.,.,47 d. Financin9................ ...........48 2. COMPARAISON OF COLONIAS IN MEXICO AND IN THE U.S. .....................53 a. Colonia Formation .............53 b. Location ..........53 c. Size and Density ................54 d. Jurisdiction............... ..........54 e. Development Standards............... ........54 f. Community Organization............. ..........55 g. OverallView of Colonias ......................55 3. -

LONE STAR STATE Stargazing

LONE STAR STATE Stargazing IndependenceTitle.com Keep Your Eyes to the Sky! These are some of the best places to stargaze in Texas Big Bend National Park Big Bend National Park is not only Texas’s most famous park— it is also known as one of the most outstanding places in North America for star gazing. Thanks to the sparse human occupation of this region, it has the least light pollution of any other National Park unit in the lower 48 states. This can be a real surprise to visitors when they are outside in Big Bend at night and see the Milky Way in its full glory for perhaps the first time in their life. Needless to say, you can stargaze just about anywhere in Big Bend, but there are a few spots you might want to consider. If you’re an admirer of astronomy, bring your telescope to the Marathon Sky Park. You can also see the stars from the stargazing platform atop Eve’s Garden Bed and Breakfast in Marathon. Brazos Bend State Park Located an hour outside of Houston, Brazos Bend State Park is a great place for any astronomical enthusiast. Not only is it far removed from the light pollution of the Lone Star State’s biggest city, it’s home to the George Observatory, where visitors can view planetary objects up close and personal. LONE STAR STATE Caprock Canyons State Park Home to the only wild bison herd in the state of Texas, Caprock Canyon State Park in the Texas panhandle has stunning views of constellations. -

SUBCOMMITTEE on ARTICLES VI, VII, & VIII AGENDA MONDAY, MAY 2, 2016 10:00 A.M. ROOM E1.030 I. II. Charge #17: Review Histori

TEXAS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS SUBCOMMITTEE ON ARTICLES VI, VII, & VIII LARRY GONZALES, CHAIR AGENDA MONDAY, MAY 2, 2016 10:00 A.M. ROOM E1.030 I. CALL TO ORDER II. CHAIRMAN’S OPENING REMARKS III. INVITED TESTIMONY Charge #17: Review historic funding levels and methods of financing for the state parks system. Study recent legislative enactments including the General Appropriations Act(84R), HB 158 (84R), and SB 1366 (84R) to determine the effect of the significant increase in funding, specifically capital program funding, on parks across the state. LEGISLATIVE BUDGET BOARD • Michael Wales, Analyst • Mark Wiles, Manager, Natural Resources & Judiciary Team TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE DEPARTMENT • Carter Smith, Executive Director • Brent Leisure, State Park Division Director • Jessica Davisson, Infrastructure Division Director IV. PUBLIC TESTIMONY V. FINAL COMMENTS VI. ADJOURNMENT Overview of State Park System Funding PRESENTED TO HOUSE APPROPRIATIONS SUBCOMMITTEE ON ARTICLES VI, VIII, AND VIII LEGISLATIVE BUDGET BOARD STAFF MAY 2016 Overview of State Park System Funding The Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) state parks system consists of 95 State Historic Sites, State Natural Areas, and State Parks, of which 91 are open to the public. State park-related appropriations fund operating the sites, the maintenance and capital improvements of state park infrastructure, associated administrative functions, providing grants to local parks and other entities for recreation opportunities, and advertising and publications related to the parks system. ● Total state parks-related appropriations for the 2016-17 biennium totals $375.9 million in All Funds, an increase of $83.6 million, or 28.6 percent , above the 2014-15 actual funding level. -

Bibliography-Of-Texas-Speleology

1. Anonymous. n.d. University of Texas Bulletin No. 4631, pp. 51. 2. Anonymous. 1992. Article on Pendejo Cave. Washington Post, 10 February 1992. 3. Anonymous. 1992. Article on bats. Science News, 8 February 1992. 4. Anonymous. 2000. National Geographic, 2000 (December). 5. Anonymous. n.d. Believe odd Texas caves is Confederate mine; big rock door may be clue to mystery. 6. Anonymous. n.d. The big dig. Fault Zone, 4:8. 7. Anonymous. n.d. Cannibals roam Texas cave. Georgetown (?). 8. Anonymous. n.d. Cavern under highway is plugged by road crew. Source unknown. 9. Anonymous. n.d. Caverns of Sonora: Better Interiors. Olde Mill Publ. Co., West Texas Educators Credit Union. 10. Anonymous. n.d. Crawling, swimming spelunkers discover new rooms of cave. Austin(?). Source unknown. 11. Anonymous. n.d. Discovery (of a sort) in Airmen's Cave. Fault Zone, 5:16. 12. Anonymous. n.d. Footnotes. Fault Zone, 5:13. 13. Anonymous. n.d. Help the blind... that is, the Texas blind salamander [Brochure]: Texas Nature Conservancy. 2 pp. 14. Anonymous. n.d. Honey Creek map. Fault Zone, 4:2. 15. Anonymous. n.d. The Langtry mini-project. Fault Zone, 5:3-5. 16. Anonymous. n.d. Neuville or Gunnels Cave. http:// www.shelbycountytexashistory.org/neuvillecave.htm [accessed 9 May 2008]. 17. Anonymous. n.d. Palo Duro Canyon State Scenic Park. Austin: Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. 2 pp. 18. Anonymous. n.d. Texas blind salamander (Typhlomolge rathbuni). Mississippi Underground Dispatch, 3(9):8. 19. Anonymous. n.d. The TSA at Cascade Caverns. Fault Zone, 4:1-3, 7-8. -

Community Service Worksheet

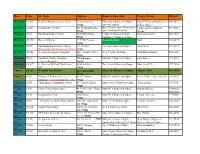

Place Code Site Name Address Hours of Operation Contact Person Phone # Westside CS116 Franklin Mountains State Park Transmountain Mon-Sun 8:00am to 5:00pm Robert Pichardo/Raul Gomez 566-6441 79912 MALES ONLY & Erika Rubio Westside CS127 Galatzan Rec Center 650 Wallenberg Dr. Mon - Th 1pm to 9pm; Friday 1pm to Carlos Apodaca Robert 581-5182 79912 6pm; Saturday 9am to 2pm Owens Westside CS27 Don Haskins Rec Center 7400 High Ridge Fridays 2:00pm to 6:00pm Rick Armendariz 587-1623 79912 Saturdays 9:00am to 2:00pm Westside CS140 Rescue Mission 1949 W. Paisano Residents Only Staff 532-2575 79922 Westside CS101 Environmental Services (West) 121 Atlantic Tue-Sat 8:00am to 4:00pm Jose Flores 873-8633 Martin Sandiego/Main Supervisor 472-4844 79922 Westside CS142 Westside Regional Command 4801 Osborne Drive Wed 7:00am-10:00am Orlando Hernandez 585-6088 79922 Canutillo CS111 Canutillo County Nutrition 7361 Bosque Mon-Fri 9:00am to 1:00pm Irma Torres 877-2622 (close to Westside) 79835 Canutillo CS117 St. Vincent De Paul Thrift Store 6950 3rd Street Tues-Sat 10:00am to 6:00pm Mari Cruz P. Lee 877-7030 (W) 79835 Vinton CS143 Westside Field Office 435 Vinton Rd Mon-Fri 8:00am to 6:00pm. Support Staff 886-1040 79821 Vinton CS67 Village of Vinton-(close to 436 E. Vinton Mon-Fri 8:00am to 4:00pm Perch Valdez, José Alarcón 383-6993 Anthony) avail for light duty- No 79821 Central- CS53 Chihuahuita Community Center 417 Charles Road Mon - Fri 11:00am to 6:00pm Patricia Rios 533-6909 DT 79901 Central- CS11 Civic Center Maintenance #1 Civic Center Plaza Mon-Fri 6:00am to 4:00pm Manny Molina 534-0626/ DT 79901 534-0644 Central- CS14 Opportunity Center 1208 Myrtle Mon-Fri 6:00am to 6:00p.m. -

Consumer Plannlng Section Comprehensive Plannlng Branch

Consumer Plannlng Section Comprehensive Plannlng Branch, Parks Division Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Austin, Texas Texans Outdoors: An Analysis of 1985 Participation in Outdoor Recreation Activities By Kathryn N. Nichols and Andrew P. Goldbloom Under the Direction of James A. Deloney November, 1989 Comprehensive Planning Branch, Parks Division Texas Parks and Wildlife Department 4200 Smith School Road, Austin, Texas 78744 (512) 389-4900 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Conducting a mail survey requires accuracy and timeliness in every single task. Each individualized survey had to be accounted for, both going out and coming back. Each mailing had to meet a strict deadline. The authors are indebted to all the people who worked on this project. The staff of the Comprehensive Planning Branch, Parks Division, deserve special thanks. This dedicated crew signed letters, mailed, remailed, coded, and entered the data of a twenty-page questionnaire that was sent to over twenty-five thousand Texans with over twelve thousand returned completed. Many other Parks Division staff outside the branch volunteered to assist with stuffing and labeling thousands of envelopes as deadlines drew near. We thank the staff of the Information Services Section for their cooperation in providing individualized letters and labels for survey mailings. We also appreciate the dedication of the staff in the mailroom for processing up wards of seventy-five thousand pieces of mail. Lastly, we thank the staff in the print shop for their courteous assistance in reproducing the various documents. Although the above are gratefully acknowledged, they are absolved from any responsibility for any errors or omissions that may have occurred. ii TEXANS OUTDOORS: AN ANALYSIS OF 1985 PARTICIPATION IN OUTDOOR RECREATION ACTIVITIES TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................................... -

Artecodevreport TCT 2010.Pdf

Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Selecting Case Study Communities & Study Approach .............................................................. 4 Texas Case Studies ...................................................................................................................... 7 City of Amarillo, Texas & Panhandle Region .......................................................................... 7 Key Findings & Lessons Learned from Amarillo & Texas Panhandle .................................. 7 Globe-News Center and Downtown Redevelopment ........................................................ 8 Window on a Wider World (WOWW) .............................................................................. 11 TEXAS the Musical Drama at the Pioneer Amphitheatre ................................................. 13 Summary .......................................................................................................................... 14 City of Clifton, Texas ............................................................................................................. 15 Key Findings & Lessons Learned from Clifton .................................................................. 15 Artists’ Colony .................................................................................................................. 16 Bosque Arts Center .......................................................................................................... -

Oklahoma, Kansas, and Texas Draft Joint EIS/BLM RMP and BIA Integrated RMP

Poster 1 Richardson County Lovewell Washington State Surface Ownership and BLM- Wildlife Lovewell Fishing Lake And Falls City Reservoir Wildlife Area St. Francis Keith Area Brown State Wildlife Sebelius Lake Norton Phillips Brown State Fishing Lake And Area Cheyenne (Norton Lake) Wildlife Area Washington Marshall County Smith County Nemaha Fishing Lake Wildlife Area County Lovewell State £77 County Administered Federal Minerals Rawlins State Park ¤ Wildlife Sabetha ¤£36 Decatur Norton Fishing Lake Area County Republic County Norton County Marysville ¤£75 36 36 Brown County ¤£ £36 County ¤£ Washington Phillipsburg ¤ Jewell County Nemaha County Doniphan County St. 283 ¤£ Atchison State County Joseph Kirwin National Glen Elder BLM-administered federal mineral estate Reservoir Jamestown Tuttle Fishing Lake Wildlife Refuge Sherman (Waconda Lake) Wildlife Area Creek Atchison State Fishing Webster Lake 83 State Glen Elder Lake And Wildlife Area County ¤£ Sheridan Nicodemus Tuttle Pottawatomie State Thomas County Park Webster Lake Wildlife Area Concordia State National Creek State Fishing Lake No. Atchison Bureau of Indian Affairs-managed surface Fishing Lake Historic Site Rooks County Parks 1 And Wildlife ¤£159 Fort Colby Cloud County Atchison Leavenworth Goodland 24 Beloit Clay County Holton 70 ¤£ Sheridan Osborne Riley County §¨¦ 24 County Glen Elder ¤£ Jackson 73 County Graham County Rooks State County ¤£ lands State Park Mitchell Clay Center Pottawatomie County Sherman State Fishing Lake And ¤£59 Leavenworth Wildlife Area County County Fishing -

Sabine Lake Galveston Bay East Matagorda Bay Matagorda Bay Corpus Christi Bay Aransas Bay San Antonio Bay Laguna Madre Planning

River Basins Brazos River Basin Brazos-Colorado Coastal Basin TPWD Canadian River Basin Dallam Sherman Hansford Ochiltree Wolf Creek Colorado River Basin Lipscomb Gene Howe WMA-W.A. (Pat) Murphy Colorado-Lavaca Coastal Basin R i t Strategic Planning a B r ve Gene Howe WMA l i Hartley a Hutchinson R n n Cypress Creek Basin Moore ia Roberts Hemphill c ad a an C C r e Guadalupe River Basin e k Lavaca River Basin Oldham r Potter Gray ive Regions Carson ed R the R ork of Wheeler Lavaca-Guadalupe Coastal Basin North F ! Amarillo Neches River Basin Salt Fork of the Red River Deaf Smith Armstrong 10Randall Donley Collingsworth Palo Duro Canyon Neches-Trinity Coastal Basin Playa Lakes WMA-Taylor Unit Pr airie D og To Nueces River Basin wn Fo rk of t he Red River Parmer Playa Lakes WMA-Dimmit Unit Swisher Nueces-Rio Grande Coastal Basin Castro Briscoe Hall Childress Caprock Canyons Caprock Canyons Trailway N orth P Red River Basin ease River Hardeman Lamb Rio Grande River Basin Matador WMA Pease River Bailey Copper Breaks Hale Floyd Motley Cottle Wilbarger W To Wichita hi ng ver Sabine River Basin te ue R Foard hita Ri er R ive Wic Riv i r Wic Clay ta ve er hita hi Pat Mayse WMA r a Riv Rive ic Eisenhower ichit r e W h W tl Caddo National Grassland-Bois D'arc 6a Nort Lit San Antonio River Basin Lake Arrowhead Lamar Red River Montague South Wichita River Cooke Grayson Cochran Fannin Hockley Lubbock Lubbock Dickens King Baylor Archer T ! Knox rin Bonham North Sulphur San Antonio-Nueces Coastal Basin Crosby r it River ive y R Bowie R B W iv os r es -

Matagorda Island State Park Legend: Matagorda Island Espiritu Santo Bay Visitor Center/ State Park and Wildlife Management Area Museum State Parks Store

Matagorda Island State Park Legend: Matagorda Island Espiritu Santo Bay Visitor Center/ State Park and Wildlife Management Area Museum State Parks Store Ordance Loop East Bay Wildlife Checkstation I. Wildlife Management Area (WMA). and Workshop Rest Rooms Twenty-two miles in length and 36,568 acres in Road size, this area offers limited recreational use Showers SEADRIFT McDowell East Drive such as nature study, birdwatching and fishing. USFS Point Headquarters Supervised hunts may be held, and fishing is 185 Matagorda Avenue Primitive Tent Sites el permitted subject to the proclamations of the ve Dri outh Group Barracks Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission. These S activities are monitored closely and may be Closed Airstrip Boat Dock restricted or prohibited if they become Beach Access Road detrimental to management goals. Victoria Chann Picnic Table Closed Airstrip II. Park Area. The remaining 7,325 acres Scenic View at the northeastern end of the island Mosquito Webb Point Bird Observation include two miles of beach Point Broad which is open to year-round Bayou visitation with receational 185 Boggy Park Recreation activities such as picnicking, Bayou Areas fishing, hiking, beachwalking, Dogger Point Live Oak Bayou nature study, swimming PORT Park Conservation O'CONNOR and primitive camping. Area Gulf Intracoastal W San Antonio Bay aterway Blackberry Island Aransas Bay Wildlife Conservation National Island Coast Guard Wildlife y Shoalwater Dewberry Station Barroom Bay Area Refuge Live Oak Point stal Waterwa Island Matagorda Dock Annex Mustang Gulf Intracoa Grass Island Lake Primary Whooping Redfish Long MAINLAND OFFICE Crane Use Area Slough Teller Espiritu Santo Bay Point AND Steamboat INFORMATION False Live Oak Point Island Bayucos CENTER Bayucos Saluria Island • Access. -

BERNAL-THESIS-2020.Pdf (5.477Mb)

BROWNWOOD: BAYTOWN’S MOST HISTORIC NEIGHBORHOOD by Laura Bernal A thesis submitted to the History Department, College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Chair of Committee: Dr. Monica Perales Committee Member: Dr. Mark Goldberg Committee Member: Dr. Kristin Wintersteen University of Houston May 2020 Copyright 2020, Laura Bernal “A land without ruins is a land without memories – a land without memories is a land without history.” -Father Abram Joseph Ryan, “A Land Without Ruins” iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, and foremost, I want to thank God for guiding me on this journey. Thank you to my family for their unwavering support, especially to my parents and sisters. Thank you for listening to me every time I needed to work out an idea and for staying up late with me as I worked on this project. More importantly, thank you for accompanying me to the Baytown Nature Center hoping to find more house foundations. I am very grateful to the professors who helped me. Dr. Monica Perales, my advisor, thank you for your patience and your guidance as I worked on this project. Thank you to my defense committee, Dr. Kristin Wintersteen and Dr. Goldberg. Your advice helped make this my best work. Additionally, I would like to thank Dr. Debbie Harwell, who encouraged me to pursue this project, even when I doubted it its impact. Thank you to the friends and co-workers who listened to my opinions and encouraged me to not give up. Lastly, I would like to thank the people I interviewed. -

Beach and Bay Access Guide

Texas Beach & Bay Access Guide Second Edition Texas General Land Office Jerry Patterson, Commissioner The Texas Gulf Coast The Texas Gulf Coast consists of cordgrass marshes, which support a rich array of marine life and provide wintering grounds for birds, and scattered coastal tallgrass and mid-grass prairies. The annual rainfall for the Texas Coast ranges from 25 to 55 inches and supports morning glories, sea ox-eyes, and beach evening primroses. Click on a region of the Texas coast The Texas General Land Office makes no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information depicted on these maps, or the data from which it was produced. These maps are NOT suitable for navigational purposes and do not purport to depict or establish boundaries between private and public land. Contents I. Introduction 1 II. How to Use This Guide 3 III. Beach and Bay Public Access Sites A. Southeast Texas 7 (Jefferson and Orange Counties) 1. Map 2. Area information 3. Activities/Facilities B. Houston-Galveston (Brazoria, Chambers, Galveston, Harris, and Matagorda Counties) 21 1. Map 2. Area Information 3. Activities/Facilities C. Golden Crescent (Calhoun, Jackson and Victoria Counties) 1. Map 79 2. Area Information 3. Activities/Facilities D. Coastal Bend (Aransas, Kenedy, Kleberg, Nueces, Refugio and San Patricio Counties) 1. Map 96 2. Area Information 3. Activities/Facilities E. Lower Rio Grande Valley (Cameron and Willacy Counties) 1. Map 2. Area Information 128 3. Activities/Facilities IV. National Wildlife Refuges V. Wildlife Management Areas VI. Chambers of Commerce and Visitor Centers 139 143 147 Introduction It’s no wonder that coastal communities are the most densely populated and fastest growing areas in the country.