February 28, 2008: a Whale of a Good Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

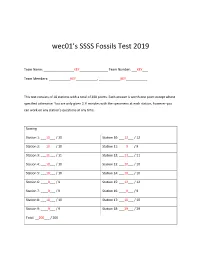

Wec01's SSSS Fossils Test 2019

wec01’s SSSS Fossils Test 2019 Team Name: _________________KEY________________ Team Number: ___KEY___ Team Members: ____________KEY____________, ____________KEY____________ This test consists of 18 stations with a total of 200 points. Each answer is worth one point except where specified otherwise. You are only given 2 ½ minutes with the specimens at each station, however you can work on any station’s questions at any time. Scoring Station 1: ___10___ / 10 Station 10: ___12___ / 12 Station 2: ___10___ / 10 Station 11: ____9___ / 9 Station 3: ___11___ / 11 Station 12: ___11___ / 11 Station 4: ___10___ / 10 Station 13: ___10___ / 10 Station 5: ___10___ / 10 Station 14: ___10___ / 10 Station 6: ____9___ / 9 Station 15: ___12___ / 12 Station 7: ____9___ / 9 Station 16: ____9___ / 9 Station 8: ___10___ / 10 Station 17: ___10___ / 10 Station 9: ____9___ / 9 Station 18: ___29___ / 29 Total: __200___ / 200 Team Number: _KEY_ Station 1: Dinosaurs (10 pt) 1. Identify the genus of specimen A Tyrannosaurus (1 pt) 2. Identify the genus of specimen B Stegosaurus (1 pt) 3. Identify the genus of specimen C Allosaurus (1 pt) 4. Which specimen(s) (A, B, or C) are A, C (1 pt) Saurischians? 5. Which two specimens (A, B, or C) lived at B, C (1 pt) the same time? 6. Identify the genus of specimen D Velociraptor (1 pt) 7. Identify the genus of specimen E Coelophysis (1 pt) 8. Which specimen (D or E) is commonly E (1 pt) found in Ghost Ranch, New Mexico? 9. Which specimen (A, B, C, D, or E) would D (1 pt) specimen F have been found on? 10. -

Storm-Dominated Shelf and Tidally-Influenced Foreshore Sedimentation, Upper Devonian Sonyea Group, Bainbridge to Sidney Center, New York

413 STORM-DOMINATED SHELF AND TIDALLY-INFLUENCED FORESHORE SEDIMENTATION, UPPER DEVONIAN SONYEA GROUP, BAINBRIDGE TO SIDNEY CENTER, NEW YORK DANIEL BISHUK JR. Groundwater and Environmental Services, Inc. (GES) 300 Gateway Park Drive North Syracuse, New York 13212 ROBERT APPLEBAUM and JAMES R. EBERT Dept. of Earth Sciences State University of New York College at Oneonta Oneonta, New York 13820-4015 INTRODUCTION The Upper Devonian paleoshoreline of the Catskill clastic wedge in New York State has been interpreted for nearly a century as a complex deltaic sequence (Barrel, 1913, 1914; Chadwick, 1933; Cooper, 1930; Sutton, Bowen and McAlester, 1970; and many others). Friedman and Johnson (1966) envisioned this deltaic complex as a series of coalescing deltaic lobes that progressively filled the Catskill epeiric sea and existed as an uninterrupted deltaic plain from New York to West Virginia. In addition, some geologists believe that such epeiric seas were tideless owing to rapid tidal wave attenuation (Shaw, 1964; and Mazzullo and Friedman, 1975). Others presume that storm (wave) processes were dominant with little or no tidal influence (Dennison, 1985). This study offers significant departures from these interpretations, by documenting nondeltaic environments with significant tidal influence along the Catskill paleo-shoreline. The purpose of this study (Fig. 1) is to delineate sedimentary environments spanning the nonmarine to marine transition in the Upper Devonian Sonyea Group and to test and challenge previous deltaic models of the Sonyea Group (Sutton, et al., 1970). Recent publications have introduced evidence for non-deltaic shoreline environments within the Catskill clastic wedge (Walker and Harms, 1971 ; 1975; Bridge and Droser, 1985; VanTassel, 1986; also see Seven, 1985, Table 1, p. -

The Largest Tropical Peat Mires in Earth History

Geological Society of America Special Paper 370 2003 Desmoinesian coal beds of the Eastern Interior and surrounding basins: The largest tropical peat mires in Earth history Stephen F. Greb William M. Andrews Cortland F. Eble Kentucky Geological Survey, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky 40506, USA William DiMichele Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C., USA C. Blaine Cecil U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia, USA James C. Hower Center for Applied Energy Research, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, USA ABSTRACT The Colchester, Springfield, and Herrin Coals of the Eastern Interior Basin are some of the most extensive coal beds in North America, if not the world. The Colchester covers an area of more than 100,000 km^, the Springfield covers 73,500-81,000 km^, and the Herrin spans 73,900 km^. Each has correlatives in the Western Interior Basin, such that their entire regional extent varies from 116,000 km^to 200,000 km^. Correlatives in the Appalachian Basin may indicate an even more widespread area of Desmoinesian peatland development, although possibly sUghtly younger in age. The Colchester Coal is thin, but the Springfield and Herrin Coals reach thicknesses in excess of 3 m. High ash yields, dominance of vitrinite macerals, and abundant lycopsids suggest that these Desmoinesian coals were deposited in topogenous (groundwater fed) to solige- nous (mixed-water source) mires. The only modern mire complexes that are as wide- spread are northern-latitude raised-bog mires, but Desmoinesian -

Devonian Brachiopods of the Tamesna Basin (Central Sahara; Algeria and North Niger)

Acta Musei Nationalis Pragae, Series B, Natural History, 60 (3–4): 61–112 issued December 2004 Sborník Národního muzea, Serie B, Přírodní vědy, 60 (3–4): 61–112 DEVONIAN BRACHIOPODS OF THE TAMESNA BASIN (CENTRAL SAHARA; ALGERIA AND NORTH NIGER). PART 1 MICHAL MERGL Department of Biology, University of West Bohemia, Klatovská 51, Plzeň, 30614, Czech Republic; e-mail: [email protected] DOMINIQUE MASSA Universite de Nice 6, Rue J. J. Rousseau, Suresnes, 92150, France Mergl, M., Massa, D. (2004): Devonian Brachiopods of the Tamesna Basin (Central Sahara; Algeria and North Niger). Part 1. – Acta Mus. Nat. Pragae, Ser. B, Hist. Nat. 60 (3-4): 61-112. Praha. ISSN 0036-5343. Abstract. The Devonian brachiopod fauna from samples collected by the late Lionel Lessard in the sixties from several secti- ons of the Lower Palaeozoic bordering the Tamesna Basin (Algeria and North Niger, south of the Ahaggar Massif) is descri- bed. The fauna is preserved in siliciclastic rocks, often lacking fine morphological details that are necessary for the determination of the fauna. Despite this difficulty, in total 40 taxa have been determined to generic, species or subspecies le- vels. One new chonetoid genus Amziella is defined on newly described species A. rahirensis. The new species Arcuaminetes racheboeufi, Montsenetes pervulgatus, Montsenetes ? drotae, Pustulatia lessardi, Pustulatia tamesnaensis, Eleutherokomma mutabilis, Mediospirifer rerhohensis and the new subspecies Tropidoleptus carinatus titanius are described. The Pragian age is suggested for the earliest brachiopod association, with maximum spread and diversity of the brachiopod fauna in Late Em- sian – Early Eifelian interval. The youngest Devonian brachiopod fauna in the available samples is probably of the Givetian age. -

Coevolution of Global Brachiopod Palaeobiogeography and Tectonopalaeogeography During the Carboniferous Ning Li1,2*, Cheng-Wen Wang1, Pu Zong3 and Yong-Qin Mao4

Li et al. Journal of Palaeogeography (2021) 10:18 https://doi.org/10.1186/s42501-021-00095-z Journal of Palaeogeography ORIGINAL ARTICLE Open Access Coevolution of global brachiopod palaeobiogeography and tectonopalaeogeography during the Carboniferous Ning Li1,2*, Cheng-Wen Wang1, Pu Zong3 and Yong-Qin Mao4 Abstract The global brachiopod palaeobiogeography of the Mississippian is divided into three realms, six regions, and eight provinces, while that of the Pennsylvanian is divided into three realms, six regions, and nine provinces. On this basis, we examined coevolutionary relationships between brachiopod palaeobiogeography and tectonopalaeogeography using a comparative approach spanning the Carboniferous. The appearance of the Boreal Realm in the Mississippian was closely related to movements of the northern plates into middle–high latitudes. From the Mississippian to the Pennsylvanian, the palaeobiogeography of Australia transitioned from the Tethys Realm to the Gondwana Realm, which is related to the southward movement of eastern Gondwana from middle to high southern latitudes. The transition of the Yukon–Pechora area from the Tethys Realm to the Boreal Realm was associated with the northward movement of Laurussia, whose northern margin entered middle–high northern latitudes then. The formation of the six palaeobiogeographic regions of Mississippian and Pennsylvanian brachiopods was directly related to “continental barriers”, which resulted in the geographical isolation of each region. The barriers resulted from the configurations of Siberia, Gondwana, and Laurussia, which supported the Boreal, Tethys, and Gondwana realms, respectively. During the late Late Devonian–Early Mississippian, the Rheic seaway closed and North America (from Laurussia) joined with South America and Africa (from Gondwana), such that the function of “continental barriers” was strengthened and the differentiation of eastern and western regions of the Tethys Realm became more distinct. -

Chesapecten, a New Genus of Pectinidae (Mollusca: Bivalvia) from the Miocene and Pliocene of Eastern North America

Chesapecten, a New Genus of Pectinidae (Mollusca: Bivalvia) From the Miocene and Pliocene of Eastern North America GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 861 Chesapecten) a New Genus of Pectinidae (Mollusca: Bivalvia) From the Miocene and Pliocene of Eastern North America By LAUCK W. WARD and BLAKE W. BLACKWELDER GEOLOGIC.AL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 861 A study of a stratigraphically important group of Pectinidae with recognition of the earliest described and figured Anzerican fossil UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON 1975 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROGERS C. B. MORTON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Ward, Lauck W Chesapecten, a new genus of Pectinidae (Mollusca, Bivalvia) from the Miocene and Pliocene of eastern North America. (Geological Survey professional paper ; 861) Includes bibliography and index. Supt. of Docs. no.: I 19.16:861 1. Chesapecten. 2. Paleontology-Tertiary. 3. Paleontology-North America. I. Blackwelder, Blake W., joint author. II. Title III. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Professional paper : 861. QE812.P4W37 564'.11 74-26694 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402- Price $1.45 (paper cover) Stock Number 2401-02574 CONTENTS Page Abstract --------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1 Introduction -------------------------------------------------.----------------------------- 1 Acknowledgments ______________________________ -

Marissa Pitter, “Unearthing the Unknown: the Fossils of The

1 Unearthing the Unknown: The Fossils of the Budden Collection Marissa Pitter Fig. 1. South Gallery Room. Hinckley, Maine: L.C. Bates Museum. Photo: John Meader Photography, ©2020. In the South Gallery Room of the L.C. Bates Museum sit eight fossil display cases. In the cramped sixth case rests a significant fossil, the Pertica quadrifaria—Maine’s state fossil which comes from the rocks of the world-renowned Trout Valley Formation. Alongside the rare fossilized remains of Pertica lies “The Budden Collection,” a group of seven fossils found in northern Maine and donated to the museum in 2013. A label sits below each fossil identifying the name of the specimen (and at times, its genus and species), the geologic period and 2 formation, and the location where the fossil was found. The exact descriptions that the L.C. Bates Museum provides on the labels is given in Table 1. Table 1. The Budden Collection Fossils Fossil Geologic Period Geologic Formation Location Favositid Coral (1) Silurian Hardwood Mountain Hobbstown Township, Maine Favositid Coral (2) Silurian Hardwood Mountain Hobbstown Township, Maine Horn coral with trace Devonian Seboomook Tomhegan Township, fossils Maine Rugose Coral Ordovician/Silurian Formation Unknown Shin Pond, Maine Brachiopod Devonian Seboomook Tomhegan Township, Mucrospirifer? Maine Brachiopods likely Devonian Formation Unknown Big Moose Township, steinkerns (fossilized Maine outlines) Leptostrophia and Devonian likely Seboomook Big Moose Township, Tentaculites Maine The question mark following “Mucrospirifer,” the unknown geologic formations, and the impreciseness of the geologic age of the rugose coral indicate there are some uncertainties among the museum’s identifications. The table also points to some commonalities among the fossil collection. -

PRISCUM the Newsletter of the Paleontological Society Volume 13, Number 2, Fall 2004

PRISCUM The Newsletter of the Paleontological Society Volume 13, Number 2, Fall 2004 Paleontological PRESIDENT’S Society Officers COLUMN: Inside... President Treasurer’s Report 2 William I. Ausich WE NEED YOU! GSA Information 2 President-Elect by William I. Ausich Reviews of PS- David Bottjer Sponsored Sessions 3 Past-President Why are you a member of The Paleontology Portal 5 Patricia H. Kelley The Paleontological Society? In PS Lecture Program 6 Secretary the not too distance past, the Books for Review 9 Roger D. K. Thomas only way to receive a copy of the Journal of Book Reviews 9 Treasurer Paleontology and Paleobiology was to pay your dues Conference Announce- and belong to the Society. I suppose one could Mark E. Patzkowsky have borrowed a copy from a friend or wander over ments 14 JP Managing Editors to the library. However, this was probably done Ann (Nancy) F. Budd with a heavy burden of guilt. Now, as we move Christopher A. Brochu into the digital age of scientific journal publishing, Jonathan Adrain one can have copies of the Journal of Paleontology and Paleobiology transmitted right to your Paleobiology Editors computer. It actually may arrive faster than the Tomasz Baumiller U.S. mail, you do not have to pay anything, and Robyn Burnham you do not even have to walk over to the library. Philip Gingerich No need for shelf space, no hassle, no dues, no Program Coordinator guilt – isn’t the Web great? The Web is great, but the Society needs dues-paying members in order Mark A. Wilson to continue to publish in paper, digitally, or both. -

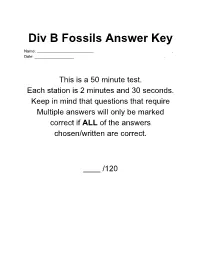

Div B Fossils Answer Key

Div B Fossils Answer Key Name: . Date: . This is a 50 minute test. Each station is 2 minutes and 30 seconds. Keep in mind that questions that require Multiple answers will only be marked correct if ALL of the answers chosen/written are correct. /120 Station 1: 1) Brachiosaurus 2) Elmer S. Riggs 3) Diplodocus 4) Cañon City, Colorado 5) Patagotitan 6) Late Cretaceous Station 2: 7) Velociraptor 8) Spinosaurus 9) Plateosaurus 10) Ankylosaurus 11) Parasaurolophus 12) Dracorex Station 3: 13) Platystrophia 14) A, C, D, E 15) Composita 16) Late Devonian-Late Permian 17) Atrypa 18) All around the world Station 4: 19) .Calymene 20) Beautiful crescent, references the glabella 21) Eldredgeops (formerly Phacops) 22) 11 23) Elrathia 24) Four axial rings Station 5: 25) A - Thorax 26) B - Genal Angle 27) C - Cephalon 28) D - Eye 29) E - Pleural furrow 30) F - Librigena 31) G - Fulcrum Station 6: 32) Order Ammonoid 33) Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction even 34) True 35) Planispirals, helically, heteromorphs 36) F Station 7: 37) Class Crinoidea 38) A 39) A characteristic of a species, meaning that it has distinct male and female individual organisms. 40) Yes 41) 600 42) 40 m (130 ft) Station 8: 43) Belemnitella 44) 84.9–66.043 Ma 45) Europe and North America 46) Internal 47) North America 48) True Station 9: 49) Bothriolepis 50) "pitted scale" or "trench scale", either or both accepted 51) Bothriolepis, keyhole, mouth 52) Three 53) a superficial -

Annual Meeting 2002

Newsletter 51 74 Newsletter 51 75 The Palaeontological Association 46th Annual Meeting 15th–18th December 2002 University of Cambridge ABSTRACTS Newsletter 51 76 ANNUAL MEETING ANNUAL MEETING Newsletter 51 77 Holocene reef structure and growth at Mavra Litharia, southern coast of Gulf of Corinth, Oral presentations Greece: a simple reef with a complex message Steve Kershaw and Li Guo Oral presentations will take place in the Physiology Lecture Theatre and, for the parallel sessions at 11:00–1:00, in the Tilley Lecture Theatre. Each presentation will run for a New perspectives in palaeoscolecidans maximum of 15 minutes, including questions. Those presentations marked with an asterisk Oliver Lehnert and Petr Kraft (*) are being considered for the President’s Award (best oral presentation by a member of the MONDAY 11:00—Non-marine Palaeontology A (parallel) Palaeontological Association under the age of thirty). Guts and Gizzard Stones, Unusual Preservation in Scottish Middle Devonian Fishes Timetable for oral presentations R.G. Davidson and N.H. Trewin *The use of ichnofossils as a tool for high-resolution palaeoenvironmental analysis in a MONDAY 9:00 lower Old Red Sandstone sequence (late Silurian Ringerike Group, Oslo Region, Norway) Neil Davies Affinity of the earliest bilaterian embryos The harvestman fossil record Xiping Dong and Philip Donoghue Jason A. Dunlop Calamari catastrophe A New Trigonotarbid Arachnid from the Early Devonian Windyfield Chert, Rhynie, Philip Wilby, John Hudson, Roy Clements and Neville Hollingworth Aberdeenshire, Scotland Tantalizing fragments of the earliest land plants Steve R. Fayers and Nigel H. Trewin Charles H. Wellman *Molecular preservation of upper Miocene fossil leaves from the Ardeche, France: Use of Morphometrics to Identify Character States implications for kerogen formation Norman MacLeod S. -

A Comparison of Environments

8-1 Trip B A COMPARISON OF ENVIRONMENTS by Thomas X. Grasso, Chairman Department of Geosciences Monroe Community College The Middle Devonian Hamilton Group ~ the Genesee Valley The Devonian System of New York State varies from carbonates at the bottom (Helderbergian and Ulsterian Sex'ies) to coarse con- tinental clastics at the top ("Chautauquan Series) and represents a westward migrating deltaic complex built during Middle and Late Devonian time, (Rickard, 1964). This deltaic complex, the Catskill Delta, is today represented by a wedge of sedimentary rock that thickens and coarsens eastward toward the Hudson River. These rocks are highly fossiliferous and structurally simple, thereby, lending themselves to detailed faunal, stratigraphic and paleoecologic studies. Since the Middle and Upper Devonian of New York represents a deltaic complex, at any instant in time during the Devonian there existed a series of transitional environments aligned approximately parallel to the old shoreline from west to east or offshore deep water to onshore shallow water. These contemporaneous environments are not only transitional with one another laterally, but they also succeed each other vertically since the delta prograded westward across New York State. Each environment is today characterized by its own distinctive rock type and fossil assemblage. For example, B-2 the fine shale deposits of the Middle Devonian in the west (Lake Erie) gradually coarsen to siltstones and sandstones eastward (Catskills). The fine shales of the Middle Devonian on Lake Erie are in turn succeeded by the ~oarser siltstones and sandstones of the Upper Devonian. The purpose of this field trip will be to sample and contraet several offshore Devonian biotopes representing two major environ ments; a poorly oxygenated phase of dark shales ("Cleveland" facies), and an oxygenated environment of soft calcareous blue-gray shales and limestones ("Moscow" facies). -

Name-Bearing Fossil Type Specimens and Taxa Named from National Park Service Areas

Sullivan, R.M. and Lucas, S.G., eds., 2016, Fossil Record 5. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 73. 277 NAME-BEARING FOSSIL TYPE SPECIMENS AND TAXA NAMED FROM NATIONAL PARK SERVICE AREAS JUSTIN S. TWEET1, VINCENT L. SANTUCCI2 and H. GREGORY MCDONALD3 1Tweet Paleo-Consulting, 9149 79th Street S., Cottage Grove, MN 55016, -email: [email protected]; 2National Park Service, Geologic Resources Division, 1201 Eye Street, NW, Washington, D.C. 20005, -email: [email protected]; 3Bureau of Land Management, Utah State Office, 440 West 200 South, Suite 500, Salt Lake City, UT 84101: -email: [email protected] Abstract—More than 4850 species, subspecies, and varieties of fossil organisms have been named from specimens found within or potentially within National Park System area boundaries as of the date of this publication. These plants, invertebrates, vertebrates, ichnotaxa, and microfossils represent a diverse collection of organisms in terms of taxonomy, geologic time, and geographic distribution. In terms of the history of American paleontology, the type specimens found within NPS-managed lands, both historically and contemporary, reflect the birth and growth of the science of paleontology in the United States, with many eminent paleontologists among the contributors. Name-bearing type specimens, whether recovered before or after the establishment of a given park, are a notable component of paleontological resources and their documentation is a critical part of the NPS strategy for their management. In this article, name-bearing type specimens of fossil taxa are documented in association with at least 71 NPS administered areas and one former monument, now abolished.