East West Journal of Humanities-VOL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABDUL HANNAN CHOWDHURY, Ph.D

ABDUL HANNAN CHOWDHURY, Ph.D. Executive Director, External Relations and Professor, School of Business North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh E-mail: [email protected] Phone: 8852000, Ext. 1717 (O), Cell: 01713063097 Permanent Address: Mailing Address: House # 35, Road # 24, Suite # 504 House # 3, Road #78, Apt # 203 Gulshan 2, Dhaka, Bangladesh Gulshan 2, Dhaka-1212, Bangladesh EDUCATION: Post Doctoral Industrial Statistics, (Concentration: Quality Improvement) September 2002 University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada. Research: Modeling censored data for quality improvement from replicated design of experiments. Ph.D. Industrial Engineering, (Area: Production Management and Applied Statistics.) September 1999 Northeastern University, Boston, USA. Thesis: Analysis of censored life test data and robust design method for reliability improvement from highly fractionated experiments. M.S. Operations Research, (Area: Decision Science and Operations Research) June 1996 Northeastern University, Boston, USA. M.Sc. Statistics, First Class, 4th Position December 1987 Department of Statistics, Jahangirnagar University, Dhaka, Bangladesh. B.Sc. (Hons.) Statistics, First Class, 6th Position, (Minor: Mathematics, Economics), July 1986 Department of Statistics, Jahangirnagar University, Dhaka, Bangladesh. EMPLOYMENT: April 2008- present Professor, School of Business, North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Teaching business statistics, operations management, Total quality management and quantitative methods classes in both the MBA and EMBA programs. -

A Psychological Perspective of Entrepreneurial Intentions Among the Business Graduates of Private Universities in Bangladesh

International Journal of Management (IJM) Volume 11, Issue 12, December 2020, pp.2682-2698, Article ID: IJM_11_12_252 Available online at http://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJM?Volume=11&Issue=12 ISSN Print: 0976-6502 and ISSN Online: 0976-6510 DOI: 10.34218/IJM.11.12.2020.252 © IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed A PSYCHOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE OF ENTREPRENEURIAL INTENTIONS AMONG THE BUSINESS GRADUATES OF PRIVATE UNIVERSITIES IN BANGLADESH Nazrul Islam School of Business, Uttara University, Dhaka, Bangladesh Nabid Aziz Tourism Management Department Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Science and Technology University, Gopalgonj, Bangladesh Mohitul Ameen Ahmed Mustafi School of Business, Uttara University, Bangladesh Amitava Bose Bapi School of Business, Uttara University, Bangladesh ABSTRACT Bangladesh is one of the youngest countries in the world with more than half of its population being under the age of 25. The nation is in the transition period towards becoming a middle income country by the year 2021. To develop an entrepreneurship- based economy and sustain its continuous growth, university graduates can play a crucial role. At present, more than two third of the business graduates are going to the job markets from the private universities of Bangladesh. They are the important segment for the future growth and development of the country. It is opined that if the business graduates are properly educated for entrepreneurship development it would have a positive impact on the economic development of Bangladesh. Hence, this study aims at identifying the psychological perspective of entrepreneurial intensions among the business graduates of private universities in Bangladesh. This study was conducted among 205 business graduates of ten private universities of Bangladesh. -

The Emergence of Multicultural London English

Contact, the feature pool and the speech community: The emergence of Multicultural London English Jenny Cheshire School of Languages Linguistics and Film Queen Mary, University of London Mile End Road London E1 4NS [email protected] fax +44 (0)20 8980 5400 tel. +44 (0)20 7882 8293 Paul Kerswill Department of Linguistics and English Language Lancaster University Lancaster LA1 4YL United Kingdom [email protected] fax +44 1524 843085 tel. +44 1524 594577 Susan Fox School of Languages Linguistics and Film Queen Mary, University of London Mile End Road London E1 4NS [email protected] fax +44 (0)20 8980 5400 tel.+44 (0)20 7882 7579 Eivind Nessa Torgersen Sør-Trøndelag University College 7004 Trondheim Norway [email protected] fax +47 73559851 tel. +47 73559790 Page 1 of 64 Contact, the feature pool and the speech community: The emergence of Multicultural London English Abstract In Northern Europe’s major cities, new varieties of the host languages are emerging in the multilingual inner cities. While some analyse these ‘multiethnolects’ as youth styles, we take a variationist approach to an emerging ‘Multicultural London English’ (MLE), asking: (1) what features characterise MLE? (2) at what age(s) are they acquired? (3) is MLE vernacularised ? (4) when did MLE emerge, and what factors enabled its emergence? We argue that innovations in the diphthongs and the quotative system are generated from the specific sociolinguistics of inner-city London, where at least half the population is undergoing group second-language acquisition and where high linguistic diversity leads to a feature pool to select from. -

![Download Journal [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5290/download-journal-pdf-465290.webp)

Download Journal [PDF]

JOURNAL OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS JOURNAL OF JOURNAL OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS Vol 5 No 1 June 2006 5 No 1 June Vol Volume 5 Number 1 June 2006 VOLUME 5 NO 1 1 Journal of African Elections ARTICLES BY Chris Landsberg Karanja Mbugua Jibrin Ibrahim Thaddeus Menang Churchill Ewumbue-Monono Bertha Chiroro Said Adejumobi Sheila Bunwaree Jeremy Seekings Tom Lodge Volume 5 Number 1 June 2006 1 2 JOURNAL OF AFRICAN ELECTIONS Published by EISA 14 Park Road, Richmond Johannesburg South Africa P O Box 740 Auckland Park 2006 South Africa Tel: +27 11 482 5495 Fax: +27 11 482 6163 e-mail: [email protected] ©EISA 2006 ISSN: 1609-4700 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher Copy editor: Pat Tucker Printed by: Global Print, Johannesburg Cover photograph: Reproduced with the permission of the HAMILL GALLERY OF AFRICAN ART, BOSTON, MA, USA www.eisa.org.za VOLUME 5 NO 1 3 EDITORS Denis Kadima, EISA, Johannesburg Khabele Matlosa, EISA, Johannesburg EDITORIAL BOARD Tessy Bakary, Office of the Prime Minister, Abidjan, Côte di’Ivoire David Caroll, Democracy Program, The Carter Center, Atlanta Jørgen Elklit, Department of Political Science, University of Aarhus, Denmark Amanda Gouws, Department of Political Science, University of Stellenbosch Abdalla Hamdok, International Institute for Democracy Assistance, Pretoria Sean Jacobs, New York University, Brooklyn, -

ABU N.M. WAHID Managing Editor, the Journal of Developing Areas

ABU N.M. WAHID Managing Editor, the Journal of Developing Areas College of Business Tennessee State University 330 Tenth Avenue North Nashville, Tennessee 37203-3401, U.S.A. Tel: Off. (615)963-7149; Res. (615)662-6420 Fax: (615)963-7139; Email: [email protected] C.V. SUMMARY Abu N. M. Wahid is a professor of economics at Tennessee State University and Managing Editor of the Journal of Developing Areas (the JDA). He was instrumental in getting the JDA relocated to Tennessee State University (TSU) from Western Illinois University in 2001. Up until now, he has published SIX books as author, editor, and co-editor. His book (Ed) Frontiers of Economics: Nobel Laureates of the Twentieth Century, has been quite popular and acquired by many major libraries around the world. His first book (Ed) The Grameen Bank: Poverty Relief in Bangladesh is a widely cited work and was used as a text on microlending at Hartwick College of New York. In addition, Dr. Wahid made nearly 60 publications in the form of refereed journal articles and book chapters. He received Fulbright research grant in 1997. The other grants he obtained were from the Japan Foundation, the American Institute of Bangladesh Studies, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, Eastern Illinois University, and Tennessee State University. In 1998, he visited Bangladesh and negotiated a comprehensive academic exchange agreement between TSU College of Business and Darul Ihsan University of Bangladesh. In 2014 he made another partnership agreement between Tennessee State University and Australian Academy of Business and Social Sciences (AABSS) under which, the JDA is publishing special issues with papers presented in the AABSS conferences. -

Lucy Sparrow Photo: Dafydd Jones 18 Hot &Coolart

FREE 18 HOT & COOL ART YOU NEVER FELT LUCY SPARROW LIKE THIS BEFORE DAFYDD JONES PHOTO: LUCY SPARROW GALLERIES ONE, TWO & THREE THE FUTURE CAN WAIT OCT LONDON’S NEW WAVE ARTISTS PROGRAMME curated by Zavier Ellis & Simon Rumley 13 – 17 OCT - VIP PREVIEW 12 OCT 6 - 9pm GALLERY ONE PETER DENCH DENCH DOES DALLAS 20 OCT - 7 NOV GALLERY TWO MARGUERITE HORNER CARS AND STREETS 20 - 30 OCT GALLERY ONE RUSSELL BAKER ICE 10 NOV – 22 DEC GALLERY TWO NEIL LIBBERT UNSEEN PORTRAITS 1958-1998 10 NOV – 22 DEC A NEW NOT-FOR-PROFIT LONDON EXHIBITION PLATFORM SUPPORTING THE FUSION OF ART, PHOTOGRAPHY & CULTURE Art Bermondsey Project Space, 183-185 Bermondsey Street London SE1 3UW Telephone 0203 441 5858 Email [email protected] MODERN BRITISH & CONTEMPORARY ART 20—24 January 2016 Business Design Centre Islington, London N1 Book Tickets londonartfair.co.uk F22_Artwork_FINAL.indd 1 09/09/2015 15:11 THE MAYOR GALLERY FORTHCOMING 21 CORK STREET, FIRST FLOOR, LONDON W1S 3LZ TEL: +44 (0) 20 7734 3558 FAX: +44 (0) 20 7494 1377 [email protected] www.mayorgallery.com EXHIBITIONS WIFREDO ARCAY CUBAN STRUCTURES THE MAYOR GALLERY 13 OCT - 20 NOV Wifredo Arcay (b. 1925, Cuba - d. 1997, France) “ETNAIRAV” 1959 Latex paint on plywood relief 90 x 82 x 8 cm 35 1/2 x 32 1/4 x 3 1/8 inches WOJCIECH FANGOR WORKS FROM THE 1960s FRIEZE MASTERS, D12 14 - 18 OCT Wojciech Fangor (b.1922, Poland) No. 15 1963 Oil on canvas 99 x 99 cm 39 x 39 inches STATE_OCT15.indd 1 03/09/2015 15:55 CAPTURED BY DAFYDD JONES i SPY [email protected] EWAN MCGREGOR EVE MAVRAKIS & Friend NICK LAIRD ZADIE SMITH GRAHAM NORTON ELENA SHCHUKINA ALESSANDRO GRASSINI-GRIMALDI SILVIA BRUTTINI VANESSA ARELLE YINKA SHONIBARE NIMROD KAMER HENRY HUDSON PHILIP COLBERT SANTA PASTERA IZABELLA ANDERSSON POPPY DELEVIGNE ALEXA CHUNG EMILIA FOX KARINA BURMAN SOPHIE DAHL LYNETTE YIADOM-BOAKYE CHIWETEL EJIOFOR EVGENY LEBEDEV MARC QUINN KENSINGTON GARDENS Serpentine Gallery summer party co-hosted by Christopher Kane. -

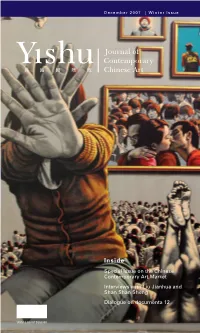

Inside Special Issue on the Chinese Contemporary Art Market Interviews with Liu Jianhua and Shan Shan Sheng Dialogue on Documenta 12

December 2007 | Winter Issue Inside Special Issue on the Chinese Contemporary Art Market Interviews with Liu Jianhua and Shan Shan Sheng Dialogue on documenta 12 US$12.00 NT$350.00 china square 1 2 Contents 4 Editor’s Note 6 Contributors 8 Contemporary Chinese Art: To Get Rich Is Glorious 11 Britta Erickson 17 The Surplus Value of Accumulation: Some Thoughts Martina Köppel-Yang 19 Seeing Through the Macro Perspective: The Chinese Art Market from 2006 to 2007 Zhao Li 23 Exhibition Culture and the Art Market 26 Yü Christina Yü 29 Interview with Zheng Shengtian at the Seven Stars Bar, 798, Beijing Britta Erickson 34 Beyond Selling Art: Galleries and the Construction of Art Market Norms Ling-Yun Tang 44 Taking Stock Joe Martin Hill 41 51 Everyday Miracles: National Pride and Chinese Collectors of Contemporary Art Simon Castets 58 Superfluous Things: The Search for “Real” Art Collectors in China Pauline J. Yao 62 After the Market’s Boom: A Case Study of the Haudenschild Collection 77 Michelle M. McCoy 72 Zhong Biao and the “Grobal” Imagination Paul Manfredi 84 Export—Cargo Transit Mathieu Borysevicz 90 About Export—Cargo Transit: An Interview with Liu Jianhua 87 Chan Ho Yeung David 93 René Block’s Waterloo: Some Impressions of documenta 12, Kassel Yang Jiechang and Martina Köppel-Yang 101 Interview with Shan Shan Sheng Brandi Reddick 109 Chinese Name Index 108 Yishu 22 errata: On page 97, image caption lists director as Liang Yin. Director’s name is Ying Liang. On page 98, image caption lists director as Xialu Guo. -

A Thematic Analysis of Bangladeshi Private University Students

AIUB Office of Research and Publications Effective Branding and Choice of University: A Thematic Analysis of Bangladeshi Private University Students Sazia Afrin AIUB Journal of Business and Economics Volume: 17 Issue Number: 1 ISSN (Online): 2706-7076 November 2020 Citation Afrin, S. (2020). Effective Branding and Choice of University: A Thematic Analysis of Bangladeshi Private University Students. AIUB Journal of Business and Economics, 17 (1), 67-90. Copyright © 2020 American International University-Bangladesh AIUB Journal of Business and Economics Volume 17, Issue 1 ISSN (PRINT) 1683-8742 ISSN (ONLINE) 2706-7076 November 2020 Page 67-90 Effective Branding and Choice of University: A Thematic Analysis of Bangladeshi Private University Students Sazia Afrin* Lecturer, Department of Accounting American International University-Bangladesh (AIUB) Corresponding author*: Sazia Afrin Email: [email protected] 67 AIUB Journal of Business and Economics, Volume 17, Number 1, November 2020 Effective Branding and Choice of University: A Thematic Analysis of Bangladeshi Private University Students Abstract: Modern marketing is greatly dependent on branding. Now every institution is using branding as its marketing tool to attract customers. Branding does not mean a logo or graphic element nowadays. Strong branding helps companies to get loyal customers. Effective branding creates trust, recognition, and popularity for companies among people. A university with a well-reputed brand has several advantages. It can easily attract students. The main objective of this paper is to determine how the branding of a private university influences student's choice of selection. For doing this, there are many relationships between branding and consumer decision making processes are mentioned. -

The International Possibilities of Insurgency and Statehood in Africa: the U.P.C

The International Possibilities of Insurgency and Statehood in Africa: The U.P.C. and Cameroon, 1948-1971. A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2013 Thomas Sharp School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Table of Contents LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................... 3 ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................... 5 DECLARATION ....................................................................................................................... 6 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT .................................................................................................. 7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 9 The U.P.C.: Historical Context and Historiography ......................................................... 13 A Fundamental Function of African Statehood ................................................................. 24 Methodology and Sources: A Transnational Approach ..................................................... 32 Structure of the Thesis ....................................................................................................... 37 CHAPTER ONE: METROPOLITAN -

ANNUAL REPORT on the Cover: Dear Friends, It Gives Me Great Pleasure to Introduce Our 2017 Annual Report

EDUCATE • INSPIRE • EMPOWER ANNUAL REPORT ON THE COVER: Dear friends, It gives me great pleasure to introduce our 2017 Annual Report. This report is a testament MASOOMA MAQSOODI to the longstanding relationships that the University has fostered; time that is significant of Afghanistan | Class of 2015 the faith our partners have in this institution and its incredible students. It is an opportunity for us to take pride in the past year, celebrate what we are, and inspire the future. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan In 2008, AUW opened as a space where women could feel forced Masooma and her family to free to concentrate on learning and socializing without the flee Afghanistan and seek refuge in constraints of extraneous norms and expectations. Over bordering Iran. There, Masooma worked these 10 years, AUW has augmented the hearts and minds as a carpenter’s assistant to earn money of over 1200 students from 15 countries across Asia and the for English and computer classes. Middle East. This would have been impossible without the commitment of the individuals and communities mentioned Masooma was admitted to Asian in these pages, nor the dedication of staff and students University for Women in 2010. As an throughout the University. We are heading towards the AUW student, Masooma participated future on secure foundations, enriched by our past and in the Women in Public Service Institute enthusiastic about the possibilities of the future. and developed a U.S. Department of State-sponsored project to study attitudes towards street harassment in Afghanistan. Following graduation, Masooma worked for the Afghanistan “ Over these 10 years, AUW has augmented the hearts and minds of over Human Rights and Democracy 1200 students from 15 countries across Asia and the Middle East. -

Towards Developing a Framework to Analyze the Qualities of the University Websites

computers Article Towards Developing a Framework to Analyze the Qualities of the University Websites Maliha Rashida 1 , Kawsarul Islam 1, A. S. M. Kayes 2,* , Mohammad Hammoudeh 3 , Mohammad Shamsul Arefin 1,* and Mohammad Ashfak Habib 1 1 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Chittagong University of Engineering and Technology, Chittagong 4349, Bangladesh; [email protected] (M.R.); [email protected] (K.I.); [email protected] (M.A.H.) 2 Department of Computer Science and Information Technology, La Trobe University, Bundoora 3086, Australia 3 Department of Computing and Mathematics, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester M15 6BH, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (A.S.M.K.); sarefi[email protected] (M.S.A.) Abstract: The website of a university is considered to be a virtual gateway to provide primary resources to its stakeholders. It can play an indispensable role in disseminating information about a university to a variety of audience at a time. Thus, the quality of an academic website requires special attention to fulfil the users’ need. This paper presents a multi-method approach of quality assessment of the academic websites, in the context of universities of Bangladesh. We developed an automated web-based tool that can evaluate any academic website based on three criteria, which are as follows: content of information, loading time and overall performance. Content of information contains many sub criteria, such as university vision and mission, faculty information, notice board and so on. This tool can also perform comparative analysis among several academic websites and Citation: Rashida, M.; Islam, K.; generate a ranked list of these. -

ICBM 2019 Conference Proceedings — Printed Version

ISBN 978-984-344-3540 http://icbm.bracu.ac.bd/ ICBM 2019 CONTENTS Message ii Message from the Conference Chairs iii Keynote Speeches iv Industry Talks viii Invited Talks xv Program Overview xxi Index of Abstracts xxiv Abstracts 1 Organizing Committee 52 Technical Committee 54 International Dignitaries 57 ICBM 2019 K M Khalid MP State Minister Ministry of Cultural Affairs Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Message It is a great honor for me to be involved with the 2nd International Conference on Business and Management (ICBM 2019), organized by Brac Business School, Brac University. I am overwhelmed to know that more than 160 research papers will be presented by 200 local and international participants. Definitely, it reflects an outstanding team work and profound activities which were accompanied by the organizing committee of ICBM 2019. I firmly believe that this conference will help the scholars to develop their career and it will be a great experience for them. Moreover, this conference would help the industry people to think more creatively. It is a great initiative taken by Brac University which will contribute towards the development of the business arena. It is creating opportunities and helping the students to explore themselves in order to fit in the workplace based on global phenomena. I am confident that in future Brac University will take such initiatives by which the society will be benefited at large. Finally, I would like to conclude with best wishes. K M Khalid MP State Minister Ministry of Cultural Affairs Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh ii ICBM 2019 MESSAGE FROM THE CONFERENCE CHAIRS Professor Vincent Chang, PhD Honorary General Chair, ICBM 2019 Professor Mohammad Mahboob Rahman, PhD Assoc.