Understanding Theatrical Aurality Through Annie Baker's Plays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beginning Of

the beginning of THE WEDDING PLANNER (from ROMANTIC FOOLS) a short comedy by Rich Orloff (ROMANTIC FOOLS, a comic revue for one man and one woman, is published and licensed by Playscripts, Inc. www.playscripts.com) The woman enters and addresses us: WOMAN When a woman and a man become engaged – it’s a magical moment, filled with the promise of love, affection and a life overflowing with joy. Then you realize you have to plan a wedding, and that magical moment is history. For months and months, you and your betrothed have to figure out a thousand details which lead to that special day when you think, “If I can make it through this, marriage will be easy.” After all that work, I think the reason the bride and groom get to march down the aisle first is so that nobody can get between them and the champagne. To help reduce the stress of all that a wedding entails, most people turn to a professional with expertise, someone they can trust, a wedding planner. The WEDDING PLANNER (MAN) enters. MAN Did I hear you say you’re looking for a wedding planner? WOMAN Well – MAN Let me present myself. He hands her a card. WOMAN “Charles H. Hungadunga the Third, Wedding and Funeral Planner. All your needs from Married to Buried.” The Wedding Planner EXCERPT, 2 MAN I’m the only wedding planner who offers a guarantee. WOMAN A guarantee? MAN If the wedding costs more than you rake in on gifts, your second wedding’s free. Now as I see it, you want a simple wedding. -

Planning a Catholic Wedding

Planning a Catholic Wedding "Make [your wedding] a real celebration – because marriage is a celebration – a Christian celebration, not a worldly feast! … What happened in Cana 2000 years ago, happens today at every wedding celebration: that which makes your wedding full and profoundly true will be the presence of the Lord who reveals himself and gives his grace. It is his presence that offers the 'good wine', he is the secret to full joy, that which truly warms the heart. "It is good that your wedding be simple and make what is truly important stand out. Some are more concerned with the exterior details, with the banquet, the photographs, the clothes, the flowers…These are important for a celebration, but only if they point to the real reason for your joy: the Lord's blessing on your love." - —Pope Francis’ address to engaged couples in Rome, February 14, 2014 Nowadays many engaged couples handle a lot of their own wedding planning. When at least one of the individuals is Catholic this can include making arrangements to be married in a Catholic church. Take time to prepare and plan The Roman Catholic Diocese of Peterborough requires a preparation period of one year for couples who want to be married in the Church. The preparation includes a contact with the parish in which they want to have their wedding. It is important to talk with the parish priest or deacon about what the parish allows and expects in a celebration. It is also possible that the parish can offer specific help and resources. -

Wedding Ringer -FULL SCRIPT W GREEN REVISIONS.Pdf

THE WEDDING RINGER FKA BEST MAN, Inc. / THE GOLDEN TUX by Jeremy Garelick & Jay Lavender GREEN REVISED - 10.22.13 YELLOW REVISED - 10.11.13 PINK REVISED - 10.1.13 BLUE REVISED - 9.17.13 WHITE SHOOTING SCRIPT - 8.27.13 Screen Gems Productions, Inc. 10202 W. Washington Blvd. Stage 6 Suite 4100 Culver City, CA 90232 GREEN REVISED 10.22.13 1 OVER BLACK A DIAL TONE...numbers DIALED...phone RINGING. SETH (V.O.) Hello? DOUG (V.O.) Oh hi, uh, Seth? SETH (V.O.) Yeah? DOUG (V.O.) It’s Doug. SETH (V.O.) Doug? Doug who? OPEN TIGHT ON DOUG Doug Harris... 30ish, on the slightly dweebier side of average. 1 REVEAL: INT. DOUG’S OFFICE - DAY 1 Organized clutter, stacks of paper cover the desk. Vintage posters/jerseys of Los Angeles sports legends adorn the walls- -ERIC DICKERSON, JIM PLUNKETT, KURT RAMBIS, STEVE GARVEY- DOUG You know, Doug Harris...Persian Rug Doug? SETH (OVER PHONE) Doug Harris! Of course. What’s up? DOUG (relieved) I know it’s been awhile, but I was calling because, I uh, have some good news...I’m getting married. SETH (OVER PHONE) That’s great. Congratulations. DOUG And, well, I was wondering if you might be interested in perhaps being my best man. GREEN REVISED 10.22.13 2 Dead silence. SETH (OVER PHONE) I have to be honest, Doug. This is kind of awkward. I mean, we don’t really know each other that well. DOUG Well...what about that weekend in Carlsbad Caverns? SETH (OVER PHONE) That was a ninth grade field trip, the whole class went. -

Crazy Rich Asians

CRAZY RICH ASIANS Screenplay by Peter Chiarelli and Adele Lim based on the novel by Kevin Kwan This script is the confidential and proprietary property of Warner Bros. Pictures and no portion of it may be performed, distributed, reproduced, used, quoted or published without prior written permission. FINAL AS FILMED Release Date Biscuit Films Sdn Bhd - Malaysia August 15, 2018 Infinite Film Pte Ltd - Singapore © 2018 4000 Warner Boulevard WARNER BROS. ENT. Burbank, California 91522 All Rights Reserved OPENING TITLES MUSIC IN. SUPERIMPOSE: Let China sleep, for when she wakes, she will shake the world. - Napoleon Bonaparte FADE IN: EXT. CALTHORPE HOTEL - NIGHT (1995) (HEAVY RAIN AND THUNDER) SUPERIMPOSE: LONDON 1995 INT. CALTHORPE HOTEL - CLOSE ON A PORTRAIT - NIGHT of a modern ENGLISH LORD. The brass placard reads: “Lord Rupert Calthorpe-Cavendish-Gore.” REVEAL we’re in the lobby of an ostentatious hotel. It’s deserted except for TWO CLERKS at the front desk. It is the middle of the night and RAINING HEAVILY outside. ANGLE ON HOTEL ENTRANCE The revolving doors start to swing as TWO CHILDREN (NICK 8, ASTRID 8) and TWO CHINESE WOMEN, ELEANOR and FELICITY YOUNG (30s) enter. They’re DRIPPING WET, dragging their soaked luggage behind them. Nick SLIDES his feet around the polished floor, leaving a MUDDY CIRCLE in his wake. The clerks look horrified. Eleanor makes her way to the front desk, while complaining to Felicity about having to walk in the bad weather. ELEANOR (in Cantonese; subtitled) If you didn’t make us walk, we wouldn’t be soaked. Felicity grabs the children by the hand and follows Eleanor to the front desk. -

Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Summer L. Williams Phone #: 617.448.5780 Email: [email protected] www.companyone.org Company One Theatre, in CollaBoration with Suffolk University, Presents THE FLICK High resolution photos availaBle here: http://www.companyone.org/Season15/The_Flick/photos_videos.shtml Boston, MA (FeBruary 2014) — Company One Theatre (C1), recently named "Boston's Best Theatre Company" By The Improper Bostonian, in collaBoration with Suffolk University, present the New England premiere of THE FLICK, By OBIE award winning playwright, Annie Baker. Performances take place FeBruary 20‐March 15, 2014 at the Suffolk University Modern Theatre (525 Washington Street, Boston, MA 02111). Tickets, from $20‐$38 , are onsale now at www.companyone.org. THE FLICK welcomes you to a run‐down movie theatre in Worcester County, MA, where Sam, Avery and Rose are navigating lives as sticky as the soda under the seats. The movies on the Big screen are no match for the tiny Battles and not‐so‐tiny heartBreaks that play out in the empty aisles. Annie Baker (THE ALIENS) and C1 Artistic Director Shawn LaCount reunite with this hilarious and heart‐rending cry for authenticity in a fast‐changing world. With this production, the artists of C1 answer the call from New England fans of one of America’s most celeBrated contemporary playwrights. Boston’s relationship with Annie Baker Began with the C1 award‐winning production of THE ALIENS as part of the Shirley, VT Plays Festival. Annie Baker (who grew up in Amherst, Massachusetts) recently won Both an OBIE for playwriting, and the Susan Smith BlackBurn Prize for THE FLICK. -

After- Inventory

Colony Club /lews jor 11 jodcrn lUonien PARTY CHAT '• TOMORROW 8-C TNI DETROIT TIMES 1945 1 Celebrates | Kline’s at 10 A. M. By FRANCES GIVENS a*o. In Mayfair TEN CANDLES twinkled on I a huge birthday cake in Mrs. j Melville's stately dining Hi th Donald I room in Edgemont Park yester- | CHAPERON day afternoon when members of THE the Colony Town Club met to of usetul celebrate a decade - . ANN AITHTKKIONIK activity. Mr and Mrv A J. daughter of Spring flowers bloomed Inventory Auchterlonie of Wing Lakt . throughout the big house and was married laM evening to Lt. members gathered about the After i 9 sew for S. R Dannuck Ji. son of S. glowing fireplaces to charity. Dannuck of South Bend. Ind R wore a gold todav the newlyweds Mrs. Melville . and crepe gown embroidered in gold are motoring 1o Monterey, CaL leaves and little ruby red flow- The candlelight ceremony was ers. Mrs. Herman Scamey in performs! by the Rev Charles black with salmon pink trim- H. Cadigan in Christ Church, ming, J\nd Mrs. J. Robert \V il- . Eleanor- Clearance Cranbrook kin, in black with an Ann wore a wedding dress of blue blouse and a hat with a white slipper satin Trimmed matching nbbort, sat near »he with seed pearls and a coronet door to handle the reservations. a WINTER APPAREL of heiri'>om Brussels lare which Mrs. Henry Wenger made STOREWIDE SAVINGS ON in her apple- ,iC »d in place the veil of bridal spring picture green with a hunch of illusion . -

Law Student, Teacher to Run for Board

Law student, teacher to run for board A township law student filed this the London School of Economic^ and studied V at Newark College of As an interested resident of challenge to the unique social the school system, I feel that I would week to seek a 3-year term on the Political Science. After graduation Engineering and Seton Hall Universi Millburn Township and as one'who is pressures and technological re- very strongly like to become involved Board of Education and a retired from college she worked afj an ty and holds memberships in Kappa vitally interested in the development quirements of the 1980's, which our in shaping the goals and directions of teacher indicated he will enter the economist for Long Island Lighting Delta Pi and Epsilon Pi Tau educa of our young people and this com young people will face.” the educational system. Our strength race tomorrow. Three 3-year terms Co. In the township she is active in tional honorary fraternities. munity I feel I am well qualified to Mrs. Schwartz’s statement on fil- is in our public schools, since they and one 1-year term will go before the National Council of Jewish Before coming to the Millburn seek a position on the Millburn Board ing follows are the cornerstone of our political ‘As for my reasons for pursuing a economy. It is necessary that the in voters here April 2. Filing deadline is Women and Temple B’nai Jeshurun. schools 25 years ago Mr. Pacelle of Education. taught in the Irvington school system “Having a strong background in position on the Board of Education, I tegrity of these most important in The law student is Sheryl Schwartz Joseph F. -

Downloaded by Michael Mitnick and Grace, Or the Art of Climbing by Lauren Feldman

The Dream Continues: American New Play Development in the Twenty-First Century by Gregory Stuart Thorson B.A., University of Oregon, 2001 M.A., University of Colorado, 2008 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theatre This thesis entitled: The Dream Continues: American New Play Development in the Twenty-First Century written by Gregory Stuart Thorson has been approved by the Department of Theatre and Dance _____________________________________ Dr. Oliver Gerland ____________________________________ Dr. James Symons Date ____________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. IRB protocol # 12-0485 iii Abstract Thorson, Gregory Stuart (Ph.D. Department of Theatre) The Dream Continues: American New Play Development in the Twenty-First Century Thesis directed by Associate Professor Oliver Gerland New play development is an important component of contemporary American theatre. In this dissertation, I examined current models of new play development in the United States. Looking at Lincoln Center Theater and Signature Theatre, I considered major non-profit theatres that seek to create life-long connections to legendary playwrights. I studied new play development at a major regional theatre, Denver Center Theatre Company, and showed how the use of commissions contribute to its new play development program, the Colorado New Play Summit. I also examined a new model of play development that has arisen in recent years—the use of small black box theatres housed in large non-profit theatre institutions. -

<I>Twenty-First Century American Playwrights</I>

The Journal of American Drama and Theatre (JADT) https://jadt.commons.gc.cuny.edu Twenty-First Century American Playwrights Twenty-First Century American Playwrights. Christopher Bigsby. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018; Pp. 228. In 1982, Christopher Bigsby penned A Critical Introduction to Twentieth-Century American Drama. What was originally planned as a single volume expanded to three, with volume 2 being released in 1984 and Volume 3 in 1985. Although Bigsby, a literary analyst and novelist with more than 50 books to his credit, hails from Britain, he is drawn to American playwrights because of their “stylistic inventiveness…sexual directness…[and] characters ranged across the social spectrum in a way that for long, and for the most part, had not been true of the English theatre” (1). This admiration brought Bigsby’s research across the millennium line to give us his latest offering Twenty-First Century American Playwrights. What Bigsby provides is an in-depth survey of nine writers who entered the American theatre landscape during the past twenty years, including chapters on Annie Baker, Frances Ya-Chu Cowhig, Katori Hall, Amy Herzog, Tracy Letts, David Lindsay-Abaire, Lynn Nottage, Sarah Ruhl, and Naomi Wallace. While these playwrights vary in the manner they work and styles of creative output, what places them together in this volume “is the sense that theatre has a unique ability to engage with audiences in search of some insight into the way we live…to witness how words become manifest, how artifice can, at its best, be the midwife of truth” (5). This explanation, however vague, does little to provide a concrete rubric for why these dramatists were included over others. -

The Wonder Years Episode & Music Guide

The Wonder Years Episode & Music Guide “What would you do if I sang out of tune … would you stand up and walk out on me?" 6 seasons, 115 episodes and hundreds of great songs – this is “The Wonder Years”. This Episode & Music Guide offers a comprehensive overview of all the episodes and all the songs played during the show. The episode guide is based on the first complete TWY episode guide which was originally posted in the newsgroup rec.arts.tv in 1993. It was compiled by Kirk Golding with contributions by Kit Kimes. It was in turn based on the first TWY episode guide ever put together by Jerry Boyajian and posted in the newsgroup rec.arts.tv in September 1991. Both are used with permission. The music guide is the work of many people. Shane Hill and Dawayne Melancon corrected and inserted several songs. Kyle Gittins revised the list; Matt Wilson and Arno Hautala provided several corrections. It is close to complete but there are still a few blank spots. Used with permission. Main Title & Score "With a little help from my friends" -- Joe Cocker (originally by Lennon/McCartney) Original score composed by Stewart Levin (episodes 1-6), W.G. Snuffy Walden (episodes 1-46 and 63-114), Joel McNelly (episodes 20,21) and J. Peter Robinson (episodes 47-62). Season 1 (1988) 001 1.01 The Wonder Years (Pilot) (original air date: January 31, 1988) We are first introduced to Kevin. They begin Junior High, Winnie starts wearing contacts. Wayne keeps saying Winnie is Kevin's girlfriend - he goes off in the cafe and Winnie's brother, Brian, dies in Vietnam. -

2013-WHAT-Playbill-W

at The Julie Harris Stage WELLFLEET HARBOR ACTORS THEATER what.org 2013-2014 Season A Journey (with just a little mayhem) Theater Dance Opera Music Movies WHAT for Kids 2 what.org Wellfleet Harbor Actors Theater 2013-2014 3 at WHAT’s Inside... The Julie Harris Stage Theater.Dance.Opera.Music.Movies 2013 Summer Season WELLFLEET HARBOR ACTORS THEATER what.org Utility Monster ........................................................... 18 The Julie harris sTage 2357 route 6, Wellfleet, Ma This season marks the 29th anniversary of Wellfleet Summer Music Festival ............................................ 21 WhaT for Kids TenT Harbor Actors Theater. Founded in 1985, WHAT is the Six Characters in Search of an Author ..................... 22 2357 route 6, Wellfleet, Ma award-winning non-profit theater on Cape Cod that the WHAT for Kids .......................................................... 24 (508) 349-WhaT (9428) • what.org New York Times says brought “a new vigor for theater on the Cape” and the Boston Globe says “is a jewel in One Slight Hitch........................................................ 26 honorary Board Chair Board PresidenT eMeriTus Julie harris Carol green Massachusetts’ crown.” Boston Magazine named Lewis Black at WHAT ............................................... 28 18 PresidenT and Board Co-ChairMan WHAT the Best Theater in 2004 and the Boston Drama Bruce a. Bierhans, esquire August Special Events.............................................. 29 Critics Association has twice awarded WHAT its 22 21 Board Co-ChairMan prestigious Elliot Norton Award. UnHitched Cabaret John dubinsky Jazzical Fusion exeCuTive direCTor Andre Gregory: Before and After Dinner Jeffry george arTisTiC direCTor Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ............................................... 30 dan lombardo ProduCer/ProduCTion Manager Ted vitale Also inside: WhaT for Kids iMPresario stephen russell Letter from the President ........................................... -

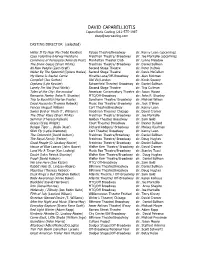

DAVID CAPARELLIOTIS Caparelliotis Casting /212-575-1987 [email protected]

DAVID CAPARELLIOTIS Caparelliotis Casting /212-575-1987 [email protected] CASTING DIRECTOR (selected) Holler If Ya Hear Me (Todd Kreidler) Palace Theatre/Broadway dir. Kenny Leon (upcoming) Casa Valentina (Harvey Fierstein) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. Joe Mantello (upcoming) Commons of Pensacola (Amanda Peet) Manhattan Theater Club dir. Lynne Meadow The Snow Geese (Sharr White) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. Daniel Sullivan All New People (Zach Braff) Second Stage Theatre dir. Peter DuBois Water By The Spoonful (Quiara Hudes) Second Stage Theatre dir. Davis McCallum My Name Is Rachel Corrie Minetta Lane/Off-Broadway dir. Alan Rickman Complicit (Joe Sutton) Old Vic/London dir. Kevin Spacey Orphans (Lyle Kessler) Schoenfeld Theatre/ Broadway dir. Daniel Sullivan Lonely I’m Not (Paul Weitz) Second Stage Theatre dir. Trip Cullman Tales of the City: the musical American Conservatory Theatre dir: Jason Moore Romantic Poetry (John P. Shanley) MTC/Off-Broadway dir: John P. Shanley Trip to Bountiful (Horton Foote) Sondheim Theatre/ Broadway dir. Michael Wilson Dead Accounts (Theresa Rebeck) Music Box Theatre/ Broadway dir. Jack O’Brien Fences (August Wilson) Cort Theatre/Broadway dir. Kenny Leon Sweet Bird of Youth (T. Williams) Goodman Theatre/ Chicago dir. David Cromer The Other Place (Sharr White) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. Joe Mantello Seminar (Theresa Rebeck) Golden Theatre/ Broadway dir. Sam Gold Grace (Craig Wright) Court Theatre/ Broadway dir. Dexter Bullard Bengal Tiger … (Rajiv Josef) Richard Rodgers/ Broadway dir. Moises Kaufman Stick Fly (Lydia Diamond) Cort Theatre/ Broadway dir. Kenny Leon The Columnist (David Auburn) Freidman Theatre/Broadway dir. Daniel Sullivan The Royal Family (Ferber) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir.