ABSTRACT by Zachary Elijah Dailey This Creative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Summer L. Williams Phone #: 617.448.5780 Email: [email protected] www.companyone.org Company One Theatre, in CollaBoration with Suffolk University, Presents THE FLICK High resolution photos availaBle here: http://www.companyone.org/Season15/The_Flick/photos_videos.shtml Boston, MA (FeBruary 2014) — Company One Theatre (C1), recently named "Boston's Best Theatre Company" By The Improper Bostonian, in collaBoration with Suffolk University, present the New England premiere of THE FLICK, By OBIE award winning playwright, Annie Baker. Performances take place FeBruary 20‐March 15, 2014 at the Suffolk University Modern Theatre (525 Washington Street, Boston, MA 02111). Tickets, from $20‐$38 , are onsale now at www.companyone.org. THE FLICK welcomes you to a run‐down movie theatre in Worcester County, MA, where Sam, Avery and Rose are navigating lives as sticky as the soda under the seats. The movies on the Big screen are no match for the tiny Battles and not‐so‐tiny heartBreaks that play out in the empty aisles. Annie Baker (THE ALIENS) and C1 Artistic Director Shawn LaCount reunite with this hilarious and heart‐rending cry for authenticity in a fast‐changing world. With this production, the artists of C1 answer the call from New England fans of one of America’s most celeBrated contemporary playwrights. Boston’s relationship with Annie Baker Began with the C1 award‐winning production of THE ALIENS as part of the Shirley, VT Plays Festival. Annie Baker (who grew up in Amherst, Massachusetts) recently won Both an OBIE for playwriting, and the Susan Smith BlackBurn Prize for THE FLICK. -

Theatre Communications Group Announces 2014 Edgerton Foundation New Play Awards

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACTS: February 15, 2015 Dafina McMillan [email protected] | 212-609-5955 Gus Schulenburg [email protected] | 212-609-5941 Theatre Communications Group Announces 2014 Edgerton Foundation New Play Awards NEW YORK, NY – Theatre Communications Group (TCG), the national organization for theatre, is pleased to announce the recipients of the Edgerton Foundation New Play Awards for the 2014-15 season. The awards, totaling $858,000, allow 25 productions extra time in the development and rehearsal of new plays with the entire creative team, helping to extend the life of the play after its first run. Over the last eight years, the Edgerton Foundation has awarded $6,977,900 to 242 TCG Member Theatre productions, enabling many plays to schedule subsequent productions following their world premieres. Fifteen have made it to Broadway, including: Curtains, 13, Next to Normal, 33 Variations, In the Next Room (or the vibrator play), Time Stands Still, Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo, A Free Man of Color, Good People, Chinglish, Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike, Bronx Bombers, Casa Valentina, Outside Mullingar and All the Way. Ten plays were nominated for Tony Awards, with All the Way and Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike winning the best play award the past two years. Eight plays were nominated for the Pulitzer Prize for Drama, with wins for The Flick (2014), Water by the Spoonful (2012) and Next to Normal (2010). “The 2013-14 season was huge for recipients of the Edgerton Foundation New Play Awards, with The Flick winning the Pulitzer, All the Way winning a Tony and Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike on top of the American Theatre Top 10 Most-Produced Plays list,” said Teresa Eyring, executive director of TCG. -

THE MYSTERY of LOVE & SEX Cast Announcement

LINCOLN CENTER THEATER CASTING ANNOUNCEMENT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE MAMOUDOU ATHIE, DIANE LANE, GAYLE RANKIN, TONY SHALHOUB TO BE FEATURED IN LINCOLN CENTER THEATER’S PRODUCTION OF “THE MYSTERY OF LOVE & SEX” A new play by BATHSHEBA DORAN Directed by SAM GOLD PREVIEWS BEGIN THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 5, 2015 OPENING NIGHT IS MONDAY, MARCH 2, 2015 AT THE MITZI E. NEWHOUSE THEATER Lincoln Center Theater (under the direction of André Bishop, Producing Artistic Director) has announced that Mamoudou Athie, Diane Lane, Gayle Rankin, and Tony Shalhoub will be featured in its upcoming production of THE MYSTERY OF LOVE & SEX, a new play by Bathsheba Doran. The production, which will be directed by Sam Gold, will begin previews Thursday, February 5 and open on Monday, March 2 at the Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater (150 West 65 Street). Deep in the American South, Charlotte and Jonny have been best friends since they were nine. She's Jewish, he's Christian, he's black, she's white. Their differences intensify their connection until sexual desire complicates everything in surprising, compulsive ways. An unexpected love story about where souls meet and the consequences of growing up. THE MYSTERY OF LOVE & SEX will have sets by Andrew Lieberman, costumes by Kaye Voyce, lighting by Jane Cox, and original music and sound by Daniel Kluger. BATHSHEBA DORAN’s plays include Kin, also directed by Sam Gold (Playwrights Horizons), Parent’s Evening (Flea Theater), Ben and the Magic Paintbrush (South Coast Repertory Theatre), Living Room in Africa (Edge Theater), Nest, Until Morning, and adaptations of Dickens’ Great Expectations, Maeterlinck’s The Blind, and Peer Gynt. -

Downloaded by Michael Mitnick and Grace, Or the Art of Climbing by Lauren Feldman

The Dream Continues: American New Play Development in the Twenty-First Century by Gregory Stuart Thorson B.A., University of Oregon, 2001 M.A., University of Colorado, 2008 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theatre This thesis entitled: The Dream Continues: American New Play Development in the Twenty-First Century written by Gregory Stuart Thorson has been approved by the Department of Theatre and Dance _____________________________________ Dr. Oliver Gerland ____________________________________ Dr. James Symons Date ____________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. IRB protocol # 12-0485 iii Abstract Thorson, Gregory Stuart (Ph.D. Department of Theatre) The Dream Continues: American New Play Development in the Twenty-First Century Thesis directed by Associate Professor Oliver Gerland New play development is an important component of contemporary American theatre. In this dissertation, I examined current models of new play development in the United States. Looking at Lincoln Center Theater and Signature Theatre, I considered major non-profit theatres that seek to create life-long connections to legendary playwrights. I studied new play development at a major regional theatre, Denver Center Theatre Company, and showed how the use of commissions contribute to its new play development program, the Colorado New Play Summit. I also examined a new model of play development that has arisen in recent years—the use of small black box theatres housed in large non-profit theatre institutions. -

<I>Twenty-First Century American Playwrights</I>

The Journal of American Drama and Theatre (JADT) https://jadt.commons.gc.cuny.edu Twenty-First Century American Playwrights Twenty-First Century American Playwrights. Christopher Bigsby. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018; Pp. 228. In 1982, Christopher Bigsby penned A Critical Introduction to Twentieth-Century American Drama. What was originally planned as a single volume expanded to three, with volume 2 being released in 1984 and Volume 3 in 1985. Although Bigsby, a literary analyst and novelist with more than 50 books to his credit, hails from Britain, he is drawn to American playwrights because of their “stylistic inventiveness…sexual directness…[and] characters ranged across the social spectrum in a way that for long, and for the most part, had not been true of the English theatre” (1). This admiration brought Bigsby’s research across the millennium line to give us his latest offering Twenty-First Century American Playwrights. What Bigsby provides is an in-depth survey of nine writers who entered the American theatre landscape during the past twenty years, including chapters on Annie Baker, Frances Ya-Chu Cowhig, Katori Hall, Amy Herzog, Tracy Letts, David Lindsay-Abaire, Lynn Nottage, Sarah Ruhl, and Naomi Wallace. While these playwrights vary in the manner they work and styles of creative output, what places them together in this volume “is the sense that theatre has a unique ability to engage with audiences in search of some insight into the way we live…to witness how words become manifest, how artifice can, at its best, be the midwife of truth” (5). This explanation, however vague, does little to provide a concrete rubric for why these dramatists were included over others. -

The Spongebob Musical in Chicago

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Chicago Press Contact: Amanda Meyer/ Tori Bryan Margie Korshak, Inc. [email protected]/[email protected] National Press Contact: Chris Boneau/Amy Kass BONEAU/BRYAN-BROWN [email protected]/ [email protected] World Premiere of Broadway Bound The SpongeBob Musical in Chicago Co-Conceived and Directed by Tina Landau Book by Kyle Jarrow Music Supervision by Tom Kitt Performances Begin on Tuesday, June 7, 2016 Limited Engagement through Sunday, July 3, 2016 at Broadway In Chicago's Oriental Theatre CHICAGO (August 31, 2015) – Broadway In Chicago is thrilled to announce the Pre-Broadway World Premiere of The SpongeBob Musical will begin performances on Tuesday, June 7 at the Oriental Theatre (24 W. Randolph St., Chicago, IL) in a limited engagement through Sunday, July 3, 2016. The SpongeBob Musical is co-conceived and directed by Tina Landau with a book by Kyle Jarrow, music supervision by Tom Kitt. The SpongeBob Musical will be a one-of-a-kind musical event with original songs by Steven Tyler and Joe Perry of AEROSMITH, Jonathan Coulton, Dirty Projectors, The Flaming Lips, John Legend, Lady Antebellum, Cyndi Lauper, Panic! At the Disco, Plain White T’s, They Might Be Giants and T.I., with an additional song by David Bowie and additional lyrics by Jonathan Coulton. The design team includes scenic and costume design by David Zinn, lighting design by Kevin Adams, projection design by Peter Nigrini and sound design by Walter Trarbach. Following its engagement in Chicago, the musical will open on Broadway in the 2016-2017 season. 1 Casting will be announced shortly. -

The Amateurs by JORDAN HARRISON FORWARD THEATER COMPANY Presents the AMATEURS by Jordan Harrison

the amateurs BY JORDAN HARRISON FORWARD THEATER COMPANY presents THE AMATEURS by Jordan Harrison Directed by Jen Uphoff Gray Scenic Designer Lighting Designer Nathan Stuber Marisa Abbott Costume Designer Composer & Sound Designer Monica Kilkus Joe Cerqua** Props Master Stage Manager Pamela Miles Sarah Deming-Henes* Dramaturg Mike Fischer The Amateurs is generously sponsored by: This play was supported in part by a grant from the Wisconsin Arts Board with funds from the State of Wisconsin and the National Endowment for the Arts, and The Evjue Foundation, Inc., the charitable arm of The Capital Times. Season Sponsors: The Shubert Foundation, The Evjue Foundation, Inc., Distillery Design, The Madison Concourse Hotel, Wisconsin Arts Board, Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television * Member of Actors’ Equity Association, the union of ** Member of United Scenic Artists Local 829 professional actors and stage managers. THE AMATEURS was produced by the VINEYARD THEATRE, Douglas Aibel, Artistic Director; Sara Stern, Artistic Director; Suzanne Appel, Managing Director; New York City, 2018 Originally commissioned by South Coast Repertory The Amateurs is produced by special arrangement with United Talent Agency THE AMATEURS 1 FORWARD THEATER COMPANY STAFF ARTISTIC Artistic Director ........................................................................................................ Jennifer Uphoff Gray Artistic Associate ...................................................................................................................Karen -

2013-WHAT-Playbill-W

at The Julie Harris Stage WELLFLEET HARBOR ACTORS THEATER what.org 2013-2014 Season A Journey (with just a little mayhem) Theater Dance Opera Music Movies WHAT for Kids 2 what.org Wellfleet Harbor Actors Theater 2013-2014 3 at WHAT’s Inside... The Julie Harris Stage Theater.Dance.Opera.Music.Movies 2013 Summer Season WELLFLEET HARBOR ACTORS THEATER what.org Utility Monster ........................................................... 18 The Julie harris sTage 2357 route 6, Wellfleet, Ma This season marks the 29th anniversary of Wellfleet Summer Music Festival ............................................ 21 WhaT for Kids TenT Harbor Actors Theater. Founded in 1985, WHAT is the Six Characters in Search of an Author ..................... 22 2357 route 6, Wellfleet, Ma award-winning non-profit theater on Cape Cod that the WHAT for Kids .......................................................... 24 (508) 349-WhaT (9428) • what.org New York Times says brought “a new vigor for theater on the Cape” and the Boston Globe says “is a jewel in One Slight Hitch........................................................ 26 honorary Board Chair Board PresidenT eMeriTus Julie harris Carol green Massachusetts’ crown.” Boston Magazine named Lewis Black at WHAT ............................................... 28 18 PresidenT and Board Co-ChairMan WHAT the Best Theater in 2004 and the Boston Drama Bruce a. Bierhans, esquire August Special Events.............................................. 29 Critics Association has twice awarded WHAT its 22 21 Board Co-ChairMan prestigious Elliot Norton Award. UnHitched Cabaret John dubinsky Jazzical Fusion exeCuTive direCTor Andre Gregory: Before and After Dinner Jeffry george arTisTiC direCTor Cat on a Hot Tin Roof ............................................... 30 dan lombardo ProduCer/ProduCTion Manager Ted vitale Also inside: WhaT for Kids iMPresario stephen russell Letter from the President ........................................... -

Hello, Dolly! Carolee Carmello

2 SHOWCASE Contents 4 Letter from the President 4 Board of Directors and Staff 7 Hello, Dolly! 23 Comprehensive Campaign 24 Institutional and Government Support 25 Individual Support 27 Matching Gifts 27 Honickman Family Society 31 Kimmel Center Staff Carolee Carmello and John Bolton in Hello, Dolly! National Tour. Photograph by Julieta Cervantes 2019 The use of cameras and recording equipment is prohibited during the performances. As a courtesy to the performers and fellow audience members, please turn off all beepers, watch alarms, and cellular phones. Latecomers and those who leave the concert hall during the performance will be seated at appropriate intervals. Showcase is published by the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts Administrative Offices, 1500 Walnut Street, 17th Floor, Philadelphia, PA 19102 For information about advertising in Showcase, contact Proud Kimmel Center Season Sponsor Onstage Publications 937-424-0529 | 866-503-1966 e-mail: [email protected] www.onstagepublications.com Official Airline of Broadway Philadelphia @KIMMELCENTER #ArtHappensHere KIMMELCENTER.ORG#ArtHappensHere 3 Kimmel Center Cultural Campus KIMMEL CENTER, INC., OFFICERS AND BOARD OF DIRECTORS Michael D. Zisman, Chairman Anne C. Ewers, President and CEO Robert R. Corrato, Vice-Chair Jane Hollingsworth, Vice-Chair Stanley Middleman, Treasurer Jami Wintz McKeon, Secretary David P. Holveck, Immediate Past Chair Bart Blatstein Jeffrey Brown Richard D. Carpenter Dear friends, Vanessa Z. Chan Reverend Luis A. Cortés, Jr. Welcome to the Academy of Music on the Kimmel Center Robert J. Delany Sr. Cultural Campus, the two-week home of this stunning revival James F. Dever, Jr. of Hello, Dolly!. Part of our 2019-20 season, boasting 44 Frances R. -

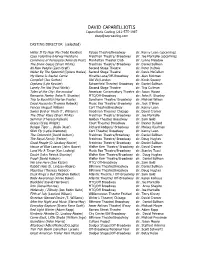

DAVID CAPARELLIOTIS Caparelliotis Casting /212-575-1987 [email protected]

DAVID CAPARELLIOTIS Caparelliotis Casting /212-575-1987 [email protected] CASTING DIRECTOR (selected) Holler If Ya Hear Me (Todd Kreidler) Palace Theatre/Broadway dir. Kenny Leon (upcoming) Casa Valentina (Harvey Fierstein) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. Joe Mantello (upcoming) Commons of Pensacola (Amanda Peet) Manhattan Theater Club dir. Lynne Meadow The Snow Geese (Sharr White) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. Daniel Sullivan All New People (Zach Braff) Second Stage Theatre dir. Peter DuBois Water By The Spoonful (Quiara Hudes) Second Stage Theatre dir. Davis McCallum My Name Is Rachel Corrie Minetta Lane/Off-Broadway dir. Alan Rickman Complicit (Joe Sutton) Old Vic/London dir. Kevin Spacey Orphans (Lyle Kessler) Schoenfeld Theatre/ Broadway dir. Daniel Sullivan Lonely I’m Not (Paul Weitz) Second Stage Theatre dir. Trip Cullman Tales of the City: the musical American Conservatory Theatre dir: Jason Moore Romantic Poetry (John P. Shanley) MTC/Off-Broadway dir: John P. Shanley Trip to Bountiful (Horton Foote) Sondheim Theatre/ Broadway dir. Michael Wilson Dead Accounts (Theresa Rebeck) Music Box Theatre/ Broadway dir. Jack O’Brien Fences (August Wilson) Cort Theatre/Broadway dir. Kenny Leon Sweet Bird of Youth (T. Williams) Goodman Theatre/ Chicago dir. David Cromer The Other Place (Sharr White) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. Joe Mantello Seminar (Theresa Rebeck) Golden Theatre/ Broadway dir. Sam Gold Grace (Craig Wright) Court Theatre/ Broadway dir. Dexter Bullard Bengal Tiger … (Rajiv Josef) Richard Rodgers/ Broadway dir. Moises Kaufman Stick Fly (Lydia Diamond) Cort Theatre/ Broadway dir. Kenny Leon The Columnist (David Auburn) Freidman Theatre/Broadway dir. Daniel Sullivan The Royal Family (Ferber) Freidman Theatre/ Broadway dir. -

Impact Stories

Our Impact: Playwright Success Stories A Few of the Bright Spots [from over 500] LIZ DUFFY ADAMS Playwrights Foundation helped to launch Liz’s career shortly after she graduated from Yale School of Drama. In 2002, her seminal work, Dog Act was developed on the Bay Area Playwrights Festival (BAPF) and then went on to its 2004 premiere in the Bay Area - with Playwrights Foundation (PF) and Shotgun Players in Berkeley, CA, winning the 2005 Glickman Award for the Bay Area’s Best New Play. The play has since been produced in San Diego, Los Angeles, New York, Massachusetts, Winnipeg, and dozens of other cities. Her next play One Big Lie was co-commissioned by Crowded Fire Theater (CFT) and PF as part of our Producing Partnership Initiative (PPI). The play received a year of development in our studio, culminating in the BAPF in 2004, and subsequently premiered in 2005 in a highly-acclaimed production at CFT. Her play The Listener was developed in PF’s Rough Readings Series (RRS), premiered in a PPI with Crowded Fire in 2008, and went on to productions in Portland and San Diego. And, her play The Train Play was chosen as part of PF’s Des Voix Festival for a French translation and reading in Paris in 2014. Subsequently, as a result of our support, Liz landed her first New York premiere for Or, at the Women’s Project, which has been produced some 50 times since. Liz’s plays have continued to live on stages nation-wide, including the Magic Theater and Seattle Rep, and won her honors including a Women of Achievement Award, a Lillian Hellman Award, and the Will Glickman Award.