Enduring Ephemera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pascas Foundation

1 “Peace And Spirit Creating Alternate Solutions” PASCAS FOUNDATION (Aust) Ltd Em: [email protected] ABN 23 133 271 593 Em: [email protected] Pascas Foundation is a not for profit organisation Queensland, Australia www.pascasworldcare.com www.pascashealth.com 2 For centuries, a small number of families have being drawing together and perfecting absolute control of all of humanity without humanity being aware. There stealth has now been revealed – read on if you want to unlock their hold over you and your family! 3 Complete list of banks owned or controlled by the Rothschild family https://jdreport.com/complete‐list‐banks‐owned‐or‐controlled‐by‐the‐rothschild‐family/ Gepubliceerd 8 augustus 2017 ∙ Bijgewerkt 26 februari 2019 “Give me control over a nations currency, and I care not who makes its laws” – Baron M.A. Rothschild https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jYZksdzVxic Before proceeding, I suggest you reading the following list of articles: 1. The Complete History of the ‘House Of Rothschild’ 2. The Complete History of the Freemasonry and the Creation of the New World Order 3. The Entire ILLUMINATI History 4. Everything about the Rothschild Zionism 5. How the Rothschilds Became the Secret Rulers of the World 4 https://www.google.com/amp/s/jdreport.com/complete‐list‐banks‐owned‐or‐controlled‐by‐the‐ rothschild‐family/ NWO: Secret Societies and Biblical Prophecy Vol. 1 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jYZksdzVxic ROTHSCHILD OWNED & CONTROLLED BANKS: Afghanistan: Bank of Afghanistan Albania: Bank of Albania Algeria: Bank of Algeria -

Ekonomski Vpliv Rodbine Rothschild

UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI EKONOMSKA FAKULTETA DIPLOMSKO DELO EKONOMSKI VPLIV RODBINE ROTHSCHILD Ljubljana, maj 2010 ALEŠ RECEK IZJAVA Študent/ka ________________________________ izjavljam, da sem avtor/ica tega diplomskega dela, ki sem ga napisal/a pod mentorstvom ________________________ , in da dovolim njegovo objavo na fakultetnih spletnih straneh. V Ljubljani, dne____________________ Podpis: _______________________________ KAZALO UVOD ........................................................................................................................................ 1 1 PREDSTAVITEV RODBINE ROTHSCHILD.................................................................. 2 1.1 VIDNI PREDSTAVNIKI RODBINE ROTHSCHILD NEKOČ IN DANES................. 5 1.1.1 Mayer Amschel (Bauer) Rothschild.......................................................................... 5 1.1.2 Nathan Mayer Rothschild.......................................................................................... 7 1.1.3 David René de Rothschild......................................................................................... 8 1.2 RODBINA ROTHSCHILD SKOZI ČAS........................................................................ 9 1.2.1 Doba od 1798 do 1820 – začetki rodbine Rothschild ............................................... 9 1.2.1.1 Frankfurtska podružnica..................................................................................... 9 1.2.1.2 Londonska podružnica ...................................................................................... -

Rothschild Frères, Maison De Commerce Et Banque, Fondée À Paris En 1817, Et Nationalisés En 1982 (Loi N°82-155 Du 11 Février 1982)

ARCHIVES NATIONALES DU MONDE DU TRAVAIL BANQUE ROTHSCHILD 132 AQ (1995 057) Introduction INTRODUCTION Activités banque, finances Présentation de l’entrée Ce fonds est entré aux Archives nationales, site de Paris, en 1972. Relevant d'un contrat de dépôt officiellement signé le 28 juin 1972 par la Banque Rothschild, il a été transféré au Centre des archives du monde du travail à Roubaix en 1995, sous le numéro d'entrée 1995 057. La gestion du fonds est passée successivement de la Banque Rothschild (1972-1982), à l'Européenne de Banque (1982-1990), à la Barclays qui rachète la précédente (1991-1994), à Eric de Rothschild (1994-2004), à The Rothschild Archive (Londres) depuis 2004. Il s'agit du fonds Rothschild qui se compose de deux sous-fonds : – le sous-fonds Rothschild Frères, maison de commerce et banque, fondée à Paris en 1817, et nationalisés en 1982 (Loi n°82-155 du 11 février 1982). Bien que formellement devenus publics (loi Archives de 1979), ces documents relèvent d'activités bancaires privées remontant au XIXe siècle et à la première moitié du XXe siècle et sont communiqués sous l'égide du contrat de dépôt stipulant l'accord préalable du déposant. – le sous-fonds Archives familiales contenant des archives privées de différents membres de la famille Rothschild, obéissant aux mêmes règles de communication. Très volumineux, il a fait l'objet de plusieurs opérations successives de classement depuis les années 1950 : Le classement des Archives nationales, site de Paris Il commence bien avant le dépôt aux Archives nationales, soit dès les années 1950, suite à la prospection de Bertrand Gille, conservateur à la Section des archives économiques et sociales des Archives nationales. -

Maîtres Anciens & Du Xixe Siècle | 13.11.2019

RTCURIAL MAÎTRES ANCIENS e & DU XIX SIÈCLE Tableaux, dessins, sculptures SIÈCLE Mercredi 13 novembre 2019 - 18h e 7 Rond-Point des Champs-Élysées 75008 Paris MAÎTRES ANCIENS & DU XIX DU & ANCIENS MAÎTRES MAÎTRES ANCIENS & DU XIXe SIÈCLE Mercredi 13 novembre 2019 - 18h artcurial.com Mercredi 13 novembre 2019 - 18h 3949 RTCURIAL RTCURIAL lot n°38, École italienne, probablement Milan, vers 1600, Saint Ambroise (détail) p.67 MAÎTRES ANCIENS & DU XIXe SIÈCLE Tableaux, dessins, sculptures Mercredi 13 novembre 2019 - 18h 7 Rond-Point des Champs-Élysées 75008 Paris lot n°38, École italienne, probablement Milan, vers 1600, Saint Ambroise (détail) p.67 lot n°109, Cornelis Kick, Bouquet de fleurs sur un entablement (détail) p.170 Assistez en direct aux ventes aux enchères d’Artcurial et enchérissez comme si vous y étiez, c’est ce que vous offre le service Artcurial Live Bid. Pour s’inscrire : www.artcurial.com 13 novembre 2019 18h. Paris RTCURIAL Maîtres anciens & du XIXe siècle 3 INDEX lot n°66, Allemagne du Sud, première partie du XVIe siècle, La Vierge à l'Enfant (détail) p.106 ÉCOLE VÉNITIENNE DU XVIe S. – 35 MOLENAER, Bartholomeus - 92 A ÉCOLE VÉNITIENNE DU XVIIIe S. – 54 MONOGRAMMISTE JF – 82 ADAM, Franz – 167 EHRENBERG, Wilhelm Schubert - 119 MOREAU, Auguste – 173 AELST, Willem van – 80 Espagne, 2nde PARTIE DU XVIIe S. - 42 MOREAU, Mathurin – 170 ALLEMAGNE DU SUD, XVIe siècle - 66 EUROPE CENTRALE FIN DU XVIe – DÉBUT MOUCHERON, Frederik de - 94 ANDALOUSIE DÉBUT DU XVIIe S. – 41 DU XVIIe S. - 57 ANQUETIN, Louis – 185 AST, Balthasar van der - 76 O F ORLEY, Richard van - 118 FAES, Peter – 135 B FLEURY, Antoine-Claude – 24, 25 BARYE, Antoine-Louis – 146, 149, FORNENBURGH, Jan Baptist van – 90 P 150, 151, 152 FRAGONARD, Jean-Honoré – 19, 20 PAYS-BAS, XVIe S. -

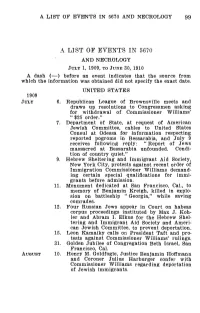

A List of Events in 5670 and Necrology 99

A LIST OF EVENTS IN 5670 AND NECROLOGY 99 A LIST OF EVENTS IN 5670 AND NECROLOGY JULY 1, 1909, TO JUNE 30, 1910 A dash (—) before an event indicates that the source from which the information was obtained did not specify the exact date. UNITED STATES 1909 JULY 6. Republican League of Brownsville meets and draws up resolutions to Congressmen asking for withdrawal of Commissioner Williams' " $25 order." 7. Department of State, at request of American Jewish Committee, cables to United States Consul at Odessa for information respecting reported pogroms in Bessarabia, and July 9 receives following reply: "Report of Jews massacred at Bessarabia unfounded. Condi- tion of country quiet." 9. Hebrew Sheltering and Immigrant Aid Society, New York City, protests against recent order of Immigration Commissioner Williams demand- ing certain special qualifications for immi- grants before admission. 11. Monument dedicated at San Francisco, Cal., to memory of Benjamin Kreigh, killed in explo- sion on battleship " Georgia," while saving comrades. 12. Four Russian Jews appear in Court on habeas corpus proceedings instituted by Max J. Koh- ler and Abram I. Elkus for the Hebrew Shel- tering and Immigrant Aid Society and Ameri- can Jewish Committee, to prevent deportation. 15. Leon Kamaiky calls on President Taft and pro- tests against Commissioner Williams' rulings. 31. Golden Jubilee of Congregation Beth Israel, San Francisco, Cal. AUGUST 10. Henry M. Goldfogle, Justice Benjamin Hoffmann and Coroner Julius Harburger confer with Commissioner Williams regarding deportation of Jewish immigrants. 100 AMERICAN JEWISH YEAR BOOK 13. Several Grand Masters of Jewish Orders meet in conference with Congressmen Goldfogle and Sabath and decide to ask Secretary Nagle for a conference. -

Rothschild Family - Wikipedia

2/29/2020 Rothschild family - Wikipedia Rothschild family The Rothschild family (/ˈrɒθstʃaɪld/) is a wealthy Jewish Rothschild family originally from Frankfurt that rose to prominence with Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744–1812), a court factor to the Jewish noble banking family German Landgraves of Hesse-Kassel in the Free City of Frankfurt, Holy Roman Empire, who established his banking business in the 1760s.[2] Unlike most previous court factors, Rothschild managed to bequeath his wealth and established an international banking family through his five sons,[3] who established themselves in London, Paris, Frankfurt, Vienna, and Naples. The family was elevated to noble rank in the Holy Roman Empire and the United Kingdom.[4][5] The family's documented history starts in 16th century Frankfurt; its name is derived from the family house, Coat of arms granted to the Barons Rothschild, built by Isaak Elchanan Bacharach in Frankfurt in Rothschild in 1822 by Emperor 1567. Francis I of Austria During the 19th century, the Rothschild family possessed the Current Western Europe largest private fortune in the world, as well as in modern world region (mainly United history.[6][7][8] The family's wealth declined over the 20th Kingdom, France, and century, and was divided among many various descendants.[9] Germany)[1] Today their interests cover a diverse range of fields, including Etymology Rothschild (German): financial services, real estate, mining, energy, mixed farming, "red shield" winemaking and nonprofits.[10][11] This article is illustrated Place of Frankfurter throughout with their buildings, which adorn landscapes across origin Judengasse, Frankfurt, northwestern Europe. Holy Roman Empire The Rothschild family has frequently been the subject of Founded 1760s (1577) [12] conspiracy theories, many of which have antisemitic origins. -

Love As Folly C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS French Paintings of the Fifteenth through Eighteenth Centuries Jean Honoré Fragonard French, 1732 - 1806 Love as Folly c. 1773/1776 oil on canvas overall (oval): 56.2 x 47.3 cm (22 1/8 x 18 5/8 in.) framed: 78.7 x 62.2 x 8.3 cm (31 x 24 1/2 x 3 1/4 in.) Inscription: lower center: frago Ailsa Mellon Bruce Collection 1970.17.111 ENTRY Fragonard repeated the compositions of the small pendant paintings known as Love as Folly and Love the Sentinel [fig. 1] numerous times during his career; a second pair also belongs to the National Gallery of Art (Love as Folly and Love the Sentinel). [1] In Love the Sentinel a chubby Cupid stands before a flowering rosebush at what appears to be the edge of a garden or park (a balustrade marking its outer limits is visible in the left and right middle ground). He looks out at the viewer, proffering an arrow in his right hand while holding his left hand to his lips; a quiver lies at his feet, and two doves fly away against a cloud-filled sky. Love as Folly shows a matching figure in a similar setting, although he flies jauntily through the air, raising aloft a stick topped by a fool’s cap; his action seems to frighten away a flock of doves, several more of which are visible on the ground. The paintings clearly were intended as a pair: they are of similar size, the subjects and scale of the figures are compatible, and the compositions balance nicely. -

The Truth About the Rothschilds

Tragedy and Hope, Inc. / 22 Briarwood Lane, East Hartford, CT 06118 October 31, 2016; ver. 26 Unabridged & Unfinished Project Title: THE TRUTH ABOUT THE ROTHSCHILDS: A MANUAL OF RESOURCES AND REFERENCES PERTAINING TO THE ROTHSCHILD FAMILY INTERNATIONAL BANKING DYNASTY Created by: Richard Grove, Tragedy and Hope dot com (All Rights Reserved) Note: The cover which follows on the next page is a 1st draft, and the gent on the tortoise is the same Baron Walter Rothschild to whom the Balfour Declaration was addressed. Page 1 of 169 www.TragedyandHope.com / www.PeaceRevolution.org Tragedy and Hope, Inc. / 22 Briarwood Lane, East Hartford, CT 06118 Page 2 of 169 www.TragedyandHope.com / www.PeaceRevolution.org Tragedy and Hope, Inc. / 22 Briarwood Lane, East Hartford, CT 06118 Table of Contents: PREFACE: INCLUDES 44 SOURCE BOOKS ON THE ROTHSCHILDS IN THE WRITING OF THIS BOOK Chapter 1: A Brief Introduction to the Rothschild International Banking Dynasty Chapter 2: PRESENT DAY / Observations on the Rothschilds & their 2014 “Inclusive Capitalism Initiative” to “Quell Global Revolt” Chapter 3: The Rothschilds in Their Own Words (From Their Own Websites) Chapter 4: International Banking: The Entries for Rothschild in various Encyclopedias Chapter 5: Colonialism: The Rothschilds, the British Empire, & Freemasonry Chapter 6: The Rothschilds, Zionism, & the Creation of the State of Israel Chapter 7: The Rothschilds & the Robber Barons Chapter 8: The Rothschilds, Cecil Rhodes, & the Rhodes Scholarship Trust Chapter 9: The Rothschilds & the creation of -

Rothschild Family

Rothschild family From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search "House of Rothschild" redirects here. For the film, see The House of Rothschild. For the German surname "Rothschild", see Rothschild (disambiguation). The Rothschild family Monaco, Luxembourg, France, Austria, Current Switzerland, Liechtenstein, United region Kingdom, United States, Cayman Islands Information Place of Frankfurt am Main origin A Rothschild house, Waddesdon Manor in Waddesdon, Buckinghamshire, donated to charity by the family in 1957. A house formerly belonging to the Viennese family (Schillersdorf Palace). Schloss Hinterleiten, one of the many palaces built by the Austrian Rothschild dynasty. Put into a trust fund charity by the family in 1905. Beatrice de Rothschild's villa on the Côte d'Azur, France Château de Montvillargenne. A Rothschild family house in Picardy, France. The Rothschild family (pron.: /ˈrɒθs.tʃaɪld/, German: [ˈʁoːt.ʃɪlt], French: [ʁɔt.ʃild], Italian: [ˈrɔtʃild]), or more simply as the Rothschilds, is a family that established a European banking dynasty starting in the late 18th century that even came to surpass leading contemporary banking families such as Baring and Berenberg. The family originates in Frankfurt. Five lines of the Austrian branch of the family have been elevated to Austrian nobility, being given hereditary titles of Barons of the Habsburg Empire by Emperor Francis II in 1816. Another line, of the British branch of the family, was elevated to British nobility at the request of Queen Victoria, being given -

Download Annual Review

The Rothschild Archive review of the year april 2006 to march 2007 THE ARCHIVE ROTHSCHILD • REVIEW OF THE YEAR 2006 – 2007 The Rothschild Archive review of the year april 2006 to march 2007 The Rothschild Archive Trust Trustees Baron Eric de Rothschild (Chair) Emma Rothschild Lionel de Rothschild Julien Sereys de Rothschild Ariane de Rothschild (from November 2006) Anthony Chapman Victor Gray Professor David Cannadine Staff Melanie Aspey (Director) Caroline Shaw (Archivist) Barbra Ruperto (Assistant Archivist) Lynne Orsatelli (Administrative Assistant, from June 2006) The Rothschild Archive, New Court, St Swithin’s Lane, London ec4p 4du Tel: +44 (0)20 7280 5874 Fax: +44 (0)20 7280 5657 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.rothschildarchive.org Company No. 3702208 Registered Charity No. 1075340 Front cover Li Hung Chang (1822‒1901) Chinese Viceroy, from an album of photographs of politicians, statesmen and religious leaders assembled by Emma, Lady Rothschild. (ral 000/848) The photograph of Li Hung Chang was sent to Nathaniel, 1st Lord Rothschild, by the sitter’s son together with a letter, dated 12 August 1896, explaining the inscription. In the letter he writes, I am sending you through Mr J H Lukach another photograph of His Excellency the Viceroy my father and hope you will be pleased with it. The characters upon the first one I sent you were written by His Excellency’s Private Secretary, but the one I am now sending you have been written by His Excellency’s own hand, those on the right hand side meaning The Chinese Ambassador Extraordinary Prime Minister Li Hung Chang presents to and on the left hand side Lord Rothschild of England, His Excellency’s age being added in this present year of the gift, viz., age 74. -

Lettres & Manuscrits Autographes

LETTRES & MANUSCRITS AUTOGRAPHES DESSINS - AQUARELLES - PHOTOGRAPHIES JEUDI 8 JUILLET 2021 PHOTOGRAPHIES - DESSINS - AUTOGRAPHES INFORMATIONS ET SERVICES POUR CETTE VENTE SELARL AGUTTES & PERRINE commissaire-priseur judiciaire RESPONSABLE DE LA VENTE SOPHIE PERRINE [email protected] EXPERT POUR CETTE VENTE THIERRY BODIN Syndicat Français des Experts Professionnels en Œuvres d’Art Tél.: +33 (0)1 45 48 25 31 [email protected] RENSEIGNEMENTS & RETRAIT DES ACHATS Uniquement sur rendez-vous MAUD VIGNON Tél.: +33 (0) 1 47 45 91 59 [email protected] Assistée de Henri Lafaye [email protected] FACTURATION ACHETEURS Tél. : +33 (0)1 41 92 06 41 [email protected] ORDRE D’ACHAT [email protected] RELATIONS PRESSE SÉBASTIEN FERNANDES Tél. : +33 (0)1 47 45 93 05 [email protected] 42 LETTRES & MANUSCRITS AUTOGRAPHES DESSINS - AQUARELLES - PHOTOGRAPHIES APRÈS LIQUIDATION JUDICIAIRE DE LA SOCIÉTÉ ARISTOPHIL JEUDI 8 JUILLET 2021, 14H30 NEUILLY-SUR-SEINE EXPOSITION PUBLIQUE NEUILLY-SUR-SEINE VENDREDI 2 JUILLET : 10H - 13H ET 14H - 17H DU LUNDI 5 AU MERCREDI 7 JUILLET : 10H - 13H ET 14H - 18H JEUDI 8 JUILLET : 10H - 12H CATALOGUE COMPLET ET RÉSULTATS VISIBLES SUR WWW.COLLECTIONS-ARISTOPHIL.COM ENCHÉRISSEZ EN LIVE SUR SELARL AGUTTES & PERRINE - COMMISSAIRE-PRISEUR JUDICIAIRE Neuilly-sur-Seine • Paris • Lyon • Aix-en-Provence • Bruxelles Suivez-nous | aguttes.com/newsletter | 1 LES COLLECTIONS ARISTOPHIL EN QUELQUES MOTS Importance C’est aujourd’hui la plus belle collection de manuscrits et autographes au monde compte tenu de la rareté et des origines illustres des œuvres qui la composent. Nombre Plus de 130 000 œuvres constituent le fonds Aristophil. L’ensemble de la collection a été trié, inventorié, authentifié, classé et conservé dans des conditions optimales, en ligne avec les normes de la BNF. -

Les Rothschild Une Dynastie De Mécènes En France

LES ROTHSCHILD UNE DYNASTIE DE MÉCÈNES EN FRANCE SOUS LA DIRECTION DE Pauline Prevost-Marcilhacy SOMOGY {BnF Éditions ÉDITIONS D'ART SOMMAIRE LES ROTHSCHILD, UNE DYNASTIE DE MÉCÈNES EN FRANCE Pauline p revost-Marcilhacy 20 EDMOND JAMES DE ROTHSCHILD, 1845-1934 Edmond James de Rothschild Pauline Prevost-Marcilhacy 42 Edmond James et Gustave de Rothschild, mécènes de l'archéologue Olivier Rayet et donateurs au musée du Louvre, J873 Alain Pasquier 60 Le trésor de Boscoreale au musée du Louvre, 1895 François Baratte 70 Dons de la baronne James Édouard et du baron Edmond James de Rothschild au département des Manuscrits de la Bibliothèque nationale, 1902-1908 François Avril 82 Dons de costumes rares du baron et de la baronne Edmond James de Rothschild au musée Carnavalet et au musée des Arts décoratifs, 1906-1908 Pascale Gorguet Ballestems 87 Le mécénat envers les artistes vivants, 1906-1920 Pauline Prevost-Marcilhacy 92 Un ensemble de moucharabiehs au musée du Louvre et au musée des Arts décoratifs, 1920 Gwenaëlle Fellinger 112 ALPHONSE DE ROTHSCHILD, 1827-1905 Alphonse de Rothschild Pauline Prevost-Marcilhacy 118 Le mécénat envers les artistes vivants en faveur des musées de région, 1895-1905 Pauline Prevost-Marcilhacy 135 CHARLOTTE DE ROTHSCHILD, 1825-1899 ET NATHANIEL DE ROTHSCHILD, 1812-1870 Charlotte et Nathaniel de Rothschild Pauline Prevost-Marcilhacy 184 Dons et legs de la baronne Nathaniel de Rothschild, 1885-1899 Pauline Prevost-Marcilhacy 200 Le goût pour la Renaissance italienne, musée du Louvre, 1899 Dominique Thiébaut 215 Un