Book Review: Ed: the Milibands and the Making of a Labour Leader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Miliband President International Rescue & Co-Chairman Global Ocean Commission

David Miliband President International Rescue & Co-Chairman Global Ocean Commission David Miliband is President and Chief Executive of International Rescue Committee (IRC), the renowned New team of over 12,000 people. The IRC helps people all over the world whose lives and livelihoods are shattered by learning and economic support to people in 40 countries, with many special programs designed for women and children. Every year, the IRC resettles thousands of refugees in 22 U.S. cities. David was the UK’s Foreign Secretary from 2007-10. Aged 41, he became the youngest person in 30 years to hold the position. He was responsible for a global network of 16,000 diplomats in over 160 countries. He established a distinctive and respected voice for an internationalist Britain, from the war in Afghanistan to the Iranian nuclear programme to engagement with the world’s emerging powers. David’s advocacy of a global role for a strong European foreign policy led to him being widely supported for the new job of EU High Representative for Foreign Aairs – a position he declined to continue his work in Britain. 1994 to 2001, authoring the manifestos on which Labour was elected to oce. As Minister for Schools from 2002 to 2004 he was regarded as a leader of reform. As Secretary of State for the Environment, he pioneered the championed the renaissance of Britain’s great cities. David set up "Movement for Change", which is training 10,000 community organisers in the UK to make changes in their own communities. He was also Vice Chairman of Sunderland Football Club until 2013. -

Research Note: Former Special Advisers in Cabinet, 1979-2013

Research Note: Former Special Advisers in Cabinet, 1979-2013 Executive Summary Sixteen special advisers have gone on to become Cabinet Ministers. This means that of the 492 special advisers listed in the Constitution Unit database in the period 1979-2010, only 3% entered Cabinet. Seven Conservative party Cabinet members were formerly special advisers. o Four Conservative special advisers went on to become Cabinet Ministers in the 1979-1997 period of Conservative governments. o Three former Conservative special advisers currently sit in the Coalition Cabinet: David Cameron, George Osborne and Jonathan Hill. Eight Labour Cabinet members between 1997-2010 were former special advisers. o Five of the eight former special advisers brought into the Labour Cabinet between 1997-2010 had been special advisers to Tony Blair or Gordon Brown. o Jack Straw entered Cabinet in 1997 having been a special adviser before 1979. One Liberal Democrat Cabinet member, Vince Cable, was previously a special adviser to a Labour minister. The Coalition Cabinet of January 2013 currently has four members who were once special advisers. o Also attending Cabinet meetings is another former special adviser: Oliver Letwin as Minister of State for Policy. There are traditionally 21 or 22 Ministers who sit in Cabinet. Unsurprisingly, the number and proportion of Cabinet Ministers who were previously special advisers generally increases the longer governments go on. The number of Cabinet Ministers who were formerly special advisers was greatest at the end of the Labour administration (1997-2010) when seven of the Cabinet Ministers were former special advisers. The proportion of Cabinet made up of former special advisers was greatest in Gordon Brown’s Cabinet when almost one-third (30.5%) of the Cabinet were former special advisers. -

How to Lead the Labour Party – It’S Not Only About Winning Office, but About Defining the Political Spectrum and Reshaping British Society

blogs.lse.ac.uk http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/2010/09/27/how-to-lead-the-labour-party-%e2%80%93- it%e2%80%99s-not-only-about-winning-office-but-about-defining-the-political-spectrum-and- reshaping-british-society/ How to lead the Labour party – it’s not only about winning office, but about defining the political spectrum and reshaping British society With Labour receiving just 29 per cent of the vote in the 2010 general election, Ed Miliband has a mountain to climb as the party’s new leader. Robin Archer argues that a purely centrist approach to his new job would be self-defeating and that he has an unusual opportunity to revive British social democracy. Debates about where Ed Miliband will lead Labour next are certain to dominate the rest of this year’s Labour conference and indeed his whole first year in office. What does the leadership of Labour require? What should his leadership strategy be? To answer, we need to examine some fundamentals. We know from opinion surveys that when UK voters’ preferences are plotted on a left-right spectrum the resulting graph typically takes the form of a bell curve. The largest numbers of voters cluster around the median voter (the person in the centre of the left/right distribution), and decreasing numbers hold positions as we move further to the left or the right. In plurality electoral systems dominated by two main parties (and even if the Alternative Vote is introduced, Britain will still fall into this category) two pure strategies are available. -

Comparing the Dynamics of Party Leadership Survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard

This is a repository copy of Comparing the dynamics of party leadership survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/82697/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Heppell, T and Bennister, M (2015) Comparing the dynamics of party leadership survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard. Government and Opposition, FirstV. 1 - 26. ISSN 1477-7053 https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2014.31 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Comparing the Dynamics of Party Leadership Survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard Abstract This article examines the interaction between the respective party structures of the Australian Labor Party and the British Labour Party as a means of assessing the strategic options facing aspiring challengers for the party leadership. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

That Was the New Labour That Wasn't

That was the New Labour that wasn’t The New Labour we got was different from the New Labour that might have been, had the reform agenda associated with stakeholding and pluralism in the early- 1990s been fully realised. Stuart White and Martin O’Neill investigate the road not taken and what it means for ‘one nation’ Labour Stuart White is a lecturer in Politics at Oxford University, specialising in political theory, and blogs at openDemocracy Martin O’Neill is Senior Lecturer in Moral & Political Philosophy in the Department of Politics at the University of York 14 / Fabian Review Essay © Kenn Goodall / bykenn.com © Kenn Goodall / bykenn.com ABOUR CURRENTLY FACES a period of challenging competitiveness in manufacturing had been undermined redefinition. New Labour is emphatically over and historically by the short-termism of the City, making for L done. But as New Labour recedes into the past, an excessively high cost of capital and consequent un- it is perhaps helpful and timely to consider what New derinvestment. German capitalism, he argued, offered an Labour might have been. It is possible to speak of a ‘New alternative model based on long-term, ‘patient’ industrial Labour That Wasn’t’: a philosophical perspective and banking. It also illustrated the benefits of structures of gov- political project which provided important context for the ernance of the firm that incorporate not only long-term rise of New Labour, and which in some ways shaped it, but investors but also labour as long-term partners – ‘stake- which New Labour also in important aspects defined itself holders’ - in enterprise management. -

Statistics Making an Impact

John Pullinger J. R. Statist. Soc. A (2013) 176, Part 4, pp. 819–839 Statistics making an impact John Pullinger House of Commons Library, London, UK [The address of the President, delivered to The Royal Statistical Society on Wednesday, June 26th, 2013] Summary. Statistics provides a special kind of understanding that enables well-informed deci- sions. As citizens and consumers we are faced with an array of choices. Statistics can help us to choose well. Our statistical brains need to be nurtured: we can all learn and practise some simple rules of statistical thinking. To understand how statistics can play a bigger part in our lives today we can draw inspiration from the founders of the Royal Statistical Society. Although in today’s world the information landscape is confused, there is an opportunity for statistics that is there to be seized.This calls for us to celebrate the discipline of statistics, to show confidence in our profession, to use statistics in the public interest and to champion statistical education. The Royal Statistical Society has a vital role to play. Keywords: Chartered Statistician; Citizenship; Economic growth; Evidence; ‘getstats’; Justice; Open data; Public good; The state; Wise choices 1. Introduction Dictionaries trace the source of the word statistics from the Latin ‘status’, the state, to the Italian ‘statista’, one skilled in statecraft, and on to the German ‘Statistik’, the science dealing with data about the condition of a state or community. The Oxford English Dictionary brings ‘statistics’ into English in 1787. Florence Nightingale held that ‘the thoughts and purpose of the Deity are only to be discovered by the statistical study of natural phenomena:::the application of the results of such study [is] the religious duty of man’ (Pearson, 1924). -

The Budget Surplus Rule Scam

Think Piece Budget 2015: The budget surplus rule scam Malcolm Sawyer University of Leeds July 2015 The budget surplus rule scam Author Malcolm Sawyer is Emeritus Professor of Economics at the Leeds University Business School, the Managing Editor of International Review of Applied Economics and Principal Investigator for a 5 year, 15 partner research project Financialisation, Economy, Society and Sustainable Development. Malcolm has authored 12 books (most recently (with Philip Arestis), Economic and Monetary Union Macroeconomic Policies: Current practices and alternatives) and edited over 25 books including the recent co-edited with Philip Arestis, Finance and the Macroeconomics of Environmental Policies. He has also published over 100 papers in refereed journals including papers on fiscal policies, alternative monetary policies, path dependency, public private partnerships and financialisation. 2 The budget surplus rule scam In a speech to at the Mansion House, London on 10th June 2015, the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer announced his intention “that, in normal times, governments of the left as well as the right should run a budget surplus to bear down on debt and prepare for an uncertain future”, and that “in the Budget we will bring forward this strong new fiscal framework to entrench this permanent commitment to that surplus, and the budget responsibility it represents.”i This ‘fiscal surplus’ law is ill-defined and is essentially unenforceable. It appears without any economic rationale as to why a budget surplus would be either desirable or indeed achievable in a sustainable manner. Mr Osborne meets Mr Micawber The rationale for a ‘budget surplus’ would appear to be along the lines of Mr Micawber’s approach in Dickens’ David Copperfield. -

Survey Report

YouGov Survey Results Sample Size: 1096 Labour Party Members Fieldwork: 27th February - 3rd March 2017 EU Ref Vote 2015 Vote Age Gender Social Grade Region Membership Length 2016 Leadership Vote Not Rest of Midlands / Pre Corbyn After Corbyn Jeremy Owen Don't Know / Total Remain Leave Lab 18-39 40-59 60+ Male Female ABC1 C2DE London North Scotland Lab South Wales leader leader Corbyn Smith Did Not Vote Weighted Sample 1096 961 101 859 237 414 393 288 626 470 743 353 238 322 184 294 55 429 667 610 377 110 Unweighted Sample 1096 976 96 896 200 351 434 311 524 572 826 270 157 330 217 326 63 621 475 652 329 115 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % Which of the following issues, if any, do you think Labour should prioritise in the future? Please tick up to three. Health 66 67 59 67 60 63 65 71 61 71 68 60 58 67 74 66 66 64 67 70 57 68 Housing 43 42 48 43 43 41 41 49 43 43 41 49 56 45 40 35 22 46 41 46 40 37 Britain leaving the EU 43 44 37 45 39 45 44 41 44 43 47 36 48 39 43 47 37 46 42 35 55 50 The economy 37 37 29 38 31 36 36 37 44 27 39 32 35 40 35 34 40 46 30 29 48 40 Education 25 26 15 26 23 28 26 22 25 26 26 24 22 25 29 23 35 26 25 26 23 28 Welfare benefits 20 19 28 19 25 15 23 23 14 28 16 28 16 21 17 21 31 16 23 23 14 20 The environment 16 17 4 15 21 20 14 13 14 19 15 18 16 21 14 13 18 8 21 20 10 19 Immigration & Asylum 10 8 32 11 10 12 10 9 12 8 10 11 12 6 9 15 6 10 10 8 12 16 Tax 10 10 11 10 8 8 12 8 11 8 8 13 9 11 10 9 8 8 11 13 6 2 Pensions 4 3 7 4 4 3 5 3 4 4 3 6 5 2 6 3 6 2 5 5 3 1 Family life & childcare 3 4 4 4 3 3 3 4 2 5 3 4 1 4 3 5 2 4 3 4 4 3 Transport 3 3 3 3 4 5 2 2 4 1 3 2 3 5 2 2 1 4 3 4 3 0 Crime 2 2 6 2 2 4 2 1 3 2 2 2 1 3 1 3 4 2 2 2 3 1 None of these 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 Don’t know 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 Now thinking about what Labour promise about Brexit going into the next general election, do you think Labour should.. -

Question Time 20 April 2008

Question Time 20 April 2008 Questions 1. Foreign Secretary David Miliband has warned Labour that squabbling over what issue raises the risk of electoral defeat? ( )Introduction of the specialist diplomas ( )Abolition of the 10p income tax rate ( )Period of detention for terrorist suspects ( )Electoral reform 2. Parliament's longest-serving female MP has died aged 77. What is her name? ( )Dame Shirley Williams ( )Gwyneth Dunwoody ( )Baroness Castle ( )Baroness Boothroyd 3. Who was accused by the Conservatives of a "blatant breach" of Whitehall election rules by making a major government announcement in the period leading up to the 1 May elections? ( )Alistair Darling ( )Lord Jones ( )Jacqui Smith ( )David Miliband 4. Lord Jones has said that he will step down from Gordon Brown's "government of all the talents" before the next general election. What position does Lord Jones currently hold? ( )Transport Minister ( )Foreign Affairs Minister ( )Education Minister ( )Trade Minister 5. Who is the only independent candidate in the race to become London Mayor? ( )Winston Paddock ( )Boris Winstanley ( )Levi Kingstone ( )Winston McKenzie 6. Ahead of the local elections on 1 May, leader Nick Clegg has claimed that the Lib Dems are ... ( )"very much the national party" ( )"destined for a heavy defeat" ( )"on a hiding to nothing" ( )"back in their constituencies and prepared for government" 7. The High Court has ruled that the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) acted unlawfully by dropping a corruption inquiry into ... ( )Contracts to build new academy schools ( )A Saudi arms deal ( )MP's expenses ( )The Crossrail project 8. Which opening will Gordon Brown not be attending? ( )Terminal 5 ( )Beijing Olympics ( )Zimbabwe's new Parliament ( )Lloyd‐Webber's new version of Oliver 9. -

Survey Report

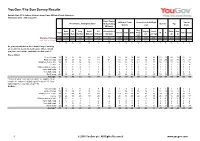

YouGov /The Sun Survey Results Sample Size: 1102 Labour Voting Labour Party Affiliated Trade Unionists Fieldwork: 27th - 29th July 2010 First Choice Affiliated Trade Yourself on Left-Right Social First Choice Voting Intention VI Excluding Gender Age Unions scale Grade Mililands Very/ Diane Ed Andy David Ed Abbott, Balls & Slightly Centre Under Over Total Unison Unite GMB Fairly M F ABC1 C2DE Abbott Balls Burnham Miliband Miliband Burnham Left and Right 40 40 Left Weighted Sample 1094 148 100 116 301 230 364 357 346 166 455 347 171 654 440 279 815 621 473 Unweighted Sample 1102 150 100 116 309 232 366 481 305 122 467 354 171 703 399 276 826 635 467 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % As you probably know, the Labour Party is holding an election to decide its next leader. Where would you place each of the candidates on this scale?* Diane Abbott Very left-wing 17 12 15 26 20 23 17 16 19 18 22 20 12 21 13 21 16 21 13 Fairly left-wing 32 50 28 42 32 34 41 33 35 31 40 42 16 34 29 22 36 36 27 Slightly left-of-centre 14 20 18 14 14 14 17 14 15 15 17 17 11 16 12 12 15 13 15 Centre 5 5 6 3 5 7 5 5 4 8 5 4 9 5 5 7 5 6 4 Slightly right-of-centre 4 1 7 2 4 4 3 3 3 5 4 2 8 3 4 3 4 4 3 Fairly right-wing 1 1 0 2 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 3 1 1 0 2 1 1 Very right-wing 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 Don't know 26 12 26 11 24 14 15 27 22 22 12 14 39 19 36 34 23 19 34 Average* -56 -57 -49 -62 -56 -57 -56 -57 -57 -53 -59 -61 -32 -57 -54 -60 -54 -59 -55 * Very left-wing=-100; fairly left-wing=-67; slightly left-of- centre=-33; centre=0; slightly right-of-centre=+33; -

Real Living Wage Now

End poverty pay scandal Real living wage now The Con-Dems tell us we're in a 'recovery'. Well, it doesn't feel that way to most of us. Far from it. While bankers get astronomical bonuses and pay, the PCS union has worked out that the real value of UK pay has fallen 7% since the start of 2008. Since 2010 there has only been one month when average pay didn't fall - and that month was skewed because of bankers' bonuses! Tory Chancellor George Osborne has floated a rise from the current rate of £6.31 an hour to £7 an hour. But this does not even reach the 'living wage', an hourly rate set independently and updated annually according to the basic cost of living in the UK. It is set at £7.65 and £8.80 in London. Today the minimum wage is at its lowest level in real terms since 2004. Millions of workers cannot make ends meet. Working Tax Credits, essential for many workers to survive, bail out low-paying Scrooge employers. Socialists stand for a minimum wage that is enough to live on and for no exemptions to that. Socialist Party member Karen Fletcher spoke to Jason (not his real name) about the reality of life on low pay. Jason is married and has a six year old son. He works with mentally disabled adults and has been in his current job for five years. He is contracted to work a minimum of 30 hours a week at £6.50 an hour. He has not had a pay rise in four years.