How to Lead the Labour Party – It’S Not Only About Winning Office, but About Defining the Political Spectrum and Reshaping British Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Labour, Old Morality

New Labour, Old Morality. In The IdeasThat Shaped Post-War Britain (1996), David Marquand suggests that a useful way of mapping the „ebbs and flows in the struggle for moral and intellectual hegemony in post-war Britain‟ is to see them as a dialectic not between Left and Right, nor between individualism and collectivism, but between hedonism and moralism which cuts across party boundaries. As Jeffrey Weeks puts it in his contribution to Blairism and the War of Persuasion (2004): „Whatever its progressive pretensions, the Labour Party has rarely been in the vanguard of sexual reform throughout its hundred-year history. Since its formation at the beginning of the twentieth century the Labour Party has always been an uneasy amalgam of the progressive intelligentsia and a largely morally conservative working class, especially as represented through the trade union movement‟ (68-9). In The Future of Socialism (1956) Anthony Crosland wrote that: 'in the blood of the socialist there should always run a trace of the anarchist and the libertarian, and not to much of the prig or the prude‟. And in 1959 Roy Jenkins, in his book The Labour Case, argued that 'there is a need for the state to do less to restrict personal freedom'. And indeed when Jenkins became Home Secretary in 1965 he put in a train a series of reforms which damned him in they eyes of Labour and Tory traditionalists as one of the chief architects of the 'permissive society': the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality, reform of the abortion and obscenity laws, the abolition of theatre censorship, making it slightly easier to get divorced. -

Research Note: Former Special Advisers in Cabinet, 1979-2013

Research Note: Former Special Advisers in Cabinet, 1979-2013 Executive Summary Sixteen special advisers have gone on to become Cabinet Ministers. This means that of the 492 special advisers listed in the Constitution Unit database in the period 1979-2010, only 3% entered Cabinet. Seven Conservative party Cabinet members were formerly special advisers. o Four Conservative special advisers went on to become Cabinet Ministers in the 1979-1997 period of Conservative governments. o Three former Conservative special advisers currently sit in the Coalition Cabinet: David Cameron, George Osborne and Jonathan Hill. Eight Labour Cabinet members between 1997-2010 were former special advisers. o Five of the eight former special advisers brought into the Labour Cabinet between 1997-2010 had been special advisers to Tony Blair or Gordon Brown. o Jack Straw entered Cabinet in 1997 having been a special adviser before 1979. One Liberal Democrat Cabinet member, Vince Cable, was previously a special adviser to a Labour minister. The Coalition Cabinet of January 2013 currently has four members who were once special advisers. o Also attending Cabinet meetings is another former special adviser: Oliver Letwin as Minister of State for Policy. There are traditionally 21 or 22 Ministers who sit in Cabinet. Unsurprisingly, the number and proportion of Cabinet Ministers who were previously special advisers generally increases the longer governments go on. The number of Cabinet Ministers who were formerly special advisers was greatest at the end of the Labour administration (1997-2010) when seven of the Cabinet Ministers were former special advisers. The proportion of Cabinet made up of former special advisers was greatest in Gordon Brown’s Cabinet when almost one-third (30.5%) of the Cabinet were former special advisers. -

New Labour, Globalization, and the Competition State" by Philip G

Centerfor European Studies Working Paper Series #70 New Labour, Globalization, and the Competition State" by Philip G. Cemy** Mark Evans" Department of Politics Department of Politics University of Leeds University of York Leeds LS2 9JT, UK York YOlO SDD, U.K Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] • Will also be published in Econonry andSocitD' - We would like to thank the Nuffield Foundation, the Center for European Studies, Harvard University,and the Max-Planck-Institut fur Gesellschaftsforshung, Cologne, for their support during the writing of this paper. Abstract The concept of the Competition State differs from the "Post-Fordist State" of Regulation Theory, which asserts that the contemporary restructuring of the state is aimed at maintaining its generic function of stabilizing the national polity and promoting the domestic economy in the public interest In contrast, the Competition State focuses on disempowering the state from within with regard to a range of key tasks, roles, and activities, in the face of processes of globalization . The state does not merely adapt to exogenous structural constraints; in addition, domestic political actors take a proactive and preemptive lead in this process through both policy entrepreneurship and the rearticulation of domestic political and social coalitions, on both right and left, as alternatives are incrementally eroded. State intervention itself is aimed at not only adjusting to but also sustaining, promoting, and expanding an open global economy in order to capture its perceived -

Comparing the Dynamics of Party Leadership Survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard

This is a repository copy of Comparing the dynamics of party leadership survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/82697/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Heppell, T and Bennister, M (2015) Comparing the dynamics of party leadership survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard. Government and Opposition, FirstV. 1 - 26. ISSN 1477-7053 https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2014.31 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Comparing the Dynamics of Party Leadership Survival in Britain and Australia: Brown, Rudd and Gillard Abstract This article examines the interaction between the respective party structures of the Australian Labor Party and the British Labour Party as a means of assessing the strategic options facing aspiring challengers for the party leadership. -

Book Review: Ed: the Milibands and the Making of a Labour Leader

blogs.lse.ac.uk http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/2011/07/16/book-review-ed-the-milibands-and-the-making-of-a-labour-leader/ Book Review: Ed: The Milibands and the Making of a Labour Leader Matthew Partridge reviews the brand new Ed Miliband biography by Mehdi Hasan and James Macintyre, published this weekend. Ed: The Milibands and the Making of a Labour Leader. By Mehdi Hassan and James Macintyre. Biteback Publishing. June 2011. Writing the first major biography of a political figure, which is what Mehdi Hasan and James Macintyre have done with Ed: The Milibands and the Making of a Labour Leader, is always challenging. The first major work looking at Margaret Thatcher did not reach the public until a year after she entered Downing Street and five years after her election as Conservative leader. Even though publishers would be quicker to respond to the rise of John Major, Tony Blair, William Hague and others, they all had relatively substantial parliamentary careers from which their biographers could draw from. Indeed, the only recent party leader with a comparably thin record was David Cameron, the present occupant of Downing Street. The parallels between the career trajectory of Miliband and Cameron, are superficially striking. For instance, both had the advantage of family connections, entered politics as advisors, took mid-career breaks and enjoyed the close patronage of their predecessors. However, while Cameron spent most of his time as a researcher in the Conservative party’s central office, his two stints with Norman Lamont and Michael Howard proved to be short lived. -

That Was the New Labour That Wasn't

That was the New Labour that wasn’t The New Labour we got was different from the New Labour that might have been, had the reform agenda associated with stakeholding and pluralism in the early- 1990s been fully realised. Stuart White and Martin O’Neill investigate the road not taken and what it means for ‘one nation’ Labour Stuart White is a lecturer in Politics at Oxford University, specialising in political theory, and blogs at openDemocracy Martin O’Neill is Senior Lecturer in Moral & Political Philosophy in the Department of Politics at the University of York 14 / Fabian Review Essay © Kenn Goodall / bykenn.com © Kenn Goodall / bykenn.com ABOUR CURRENTLY FACES a period of challenging competitiveness in manufacturing had been undermined redefinition. New Labour is emphatically over and historically by the short-termism of the City, making for L done. But as New Labour recedes into the past, an excessively high cost of capital and consequent un- it is perhaps helpful and timely to consider what New derinvestment. German capitalism, he argued, offered an Labour might have been. It is possible to speak of a ‘New alternative model based on long-term, ‘patient’ industrial Labour That Wasn’t’: a philosophical perspective and banking. It also illustrated the benefits of structures of gov- political project which provided important context for the ernance of the firm that incorporate not only long-term rise of New Labour, and which in some ways shaped it, but investors but also labour as long-term partners – ‘stake- which New Labour also in important aspects defined itself holders’ - in enterprise management. -

Survey Report

YouGov Survey Results Sample Size: 1096 Labour Party Members Fieldwork: 27th February - 3rd March 2017 EU Ref Vote 2015 Vote Age Gender Social Grade Region Membership Length 2016 Leadership Vote Not Rest of Midlands / Pre Corbyn After Corbyn Jeremy Owen Don't Know / Total Remain Leave Lab 18-39 40-59 60+ Male Female ABC1 C2DE London North Scotland Lab South Wales leader leader Corbyn Smith Did Not Vote Weighted Sample 1096 961 101 859 237 414 393 288 626 470 743 353 238 322 184 294 55 429 667 610 377 110 Unweighted Sample 1096 976 96 896 200 351 434 311 524 572 826 270 157 330 217 326 63 621 475 652 329 115 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % Which of the following issues, if any, do you think Labour should prioritise in the future? Please tick up to three. Health 66 67 59 67 60 63 65 71 61 71 68 60 58 67 74 66 66 64 67 70 57 68 Housing 43 42 48 43 43 41 41 49 43 43 41 49 56 45 40 35 22 46 41 46 40 37 Britain leaving the EU 43 44 37 45 39 45 44 41 44 43 47 36 48 39 43 47 37 46 42 35 55 50 The economy 37 37 29 38 31 36 36 37 44 27 39 32 35 40 35 34 40 46 30 29 48 40 Education 25 26 15 26 23 28 26 22 25 26 26 24 22 25 29 23 35 26 25 26 23 28 Welfare benefits 20 19 28 19 25 15 23 23 14 28 16 28 16 21 17 21 31 16 23 23 14 20 The environment 16 17 4 15 21 20 14 13 14 19 15 18 16 21 14 13 18 8 21 20 10 19 Immigration & Asylum 10 8 32 11 10 12 10 9 12 8 10 11 12 6 9 15 6 10 10 8 12 16 Tax 10 10 11 10 8 8 12 8 11 8 8 13 9 11 10 9 8 8 11 13 6 2 Pensions 4 3 7 4 4 3 5 3 4 4 3 6 5 2 6 3 6 2 5 5 3 1 Family life & childcare 3 4 4 4 3 3 3 4 2 5 3 4 1 4 3 5 2 4 3 4 4 3 Transport 3 3 3 3 4 5 2 2 4 1 3 2 3 5 2 2 1 4 3 4 3 0 Crime 2 2 6 2 2 4 2 1 3 2 2 2 1 3 1 3 4 2 2 2 3 1 None of these 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 Don’t know 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 Now thinking about what Labour promise about Brexit going into the next general election, do you think Labour should.. -

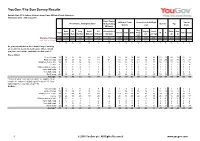

Survey Report

YouGov /The Sun Survey Results Sample Size: 1102 Labour Voting Labour Party Affiliated Trade Unionists Fieldwork: 27th - 29th July 2010 First Choice Affiliated Trade Yourself on Left-Right Social First Choice Voting Intention VI Excluding Gender Age Unions scale Grade Mililands Very/ Diane Ed Andy David Ed Abbott, Balls & Slightly Centre Under Over Total Unison Unite GMB Fairly M F ABC1 C2DE Abbott Balls Burnham Miliband Miliband Burnham Left and Right 40 40 Left Weighted Sample 1094 148 100 116 301 230 364 357 346 166 455 347 171 654 440 279 815 621 473 Unweighted Sample 1102 150 100 116 309 232 366 481 305 122 467 354 171 703 399 276 826 635 467 % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % % As you probably know, the Labour Party is holding an election to decide its next leader. Where would you place each of the candidates on this scale?* Diane Abbott Very left-wing 17 12 15 26 20 23 17 16 19 18 22 20 12 21 13 21 16 21 13 Fairly left-wing 32 50 28 42 32 34 41 33 35 31 40 42 16 34 29 22 36 36 27 Slightly left-of-centre 14 20 18 14 14 14 17 14 15 15 17 17 11 16 12 12 15 13 15 Centre 5 5 6 3 5 7 5 5 4 8 5 4 9 5 5 7 5 6 4 Slightly right-of-centre 4 1 7 2 4 4 3 3 3 5 4 2 8 3 4 3 4 4 3 Fairly right-wing 1 1 0 2 1 2 1 1 1 1 1 1 3 1 1 0 2 1 1 Very right-wing 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 Don't know 26 12 26 11 24 14 15 27 22 22 12 14 39 19 36 34 23 19 34 Average* -56 -57 -49 -62 -56 -57 -56 -57 -57 -53 -59 -61 -32 -57 -54 -60 -54 -59 -55 * Very left-wing=-100; fairly left-wing=-67; slightly left-of- centre=-33; centre=0; slightly right-of-centre=+33; -

Real Living Wage Now

End poverty pay scandal Real living wage now The Con-Dems tell us we're in a 'recovery'. Well, it doesn't feel that way to most of us. Far from it. While bankers get astronomical bonuses and pay, the PCS union has worked out that the real value of UK pay has fallen 7% since the start of 2008. Since 2010 there has only been one month when average pay didn't fall - and that month was skewed because of bankers' bonuses! Tory Chancellor George Osborne has floated a rise from the current rate of £6.31 an hour to £7 an hour. But this does not even reach the 'living wage', an hourly rate set independently and updated annually according to the basic cost of living in the UK. It is set at £7.65 and £8.80 in London. Today the minimum wage is at its lowest level in real terms since 2004. Millions of workers cannot make ends meet. Working Tax Credits, essential for many workers to survive, bail out low-paying Scrooge employers. Socialists stand for a minimum wage that is enough to live on and for no exemptions to that. Socialist Party member Karen Fletcher spoke to Jason (not his real name) about the reality of life on low pay. Jason is married and has a six year old son. He works with mentally disabled adults and has been in his current job for five years. He is contracted to work a minimum of 30 hours a week at £6.50 an hour. He has not had a pay rise in four years. -

1 Recapturing Labour's Traditions? History, Nostalgia and the Re-Writing

Recapturing Labour’s Traditions? History, nostalgia and the re-writing of Clause IV Dr Emily Robinson University of Nottingham The making of New Labour has received a great deal of critical attention, much of which has inevitably focused on the way in which it placed itself in relation to past and future, its inheritances and its iconoclasm.1 Nick Randall is right to note that students of New Labour have been particularly interested in ‘questions of temporality’ because ‘New Labour so boldly advanced a claim to disrupt historical continuity’.2 But it is not only academics who have contributed to this analysis. Many of the key figures associated with New Labour have also had their say. The New Labour project was not just about ‘making history’ in terms of its practical actions; the writing up of that history seems to have been just as important. As early as 1995 Peter Mandelson and Roger Liddle were preparing a key text designed ‘to enable everyone to understand better why Labour changed and what it has changed into’.3 This was followed in 1999 by Phillip Gould’s analysis of The Unfinished Revolution: How the Modernisers Saved the Labour Party, which motivated Dianne Hayter to begin a PhD in order to counteract the emerging consensus that the modernisation process began with the appointment of Gould and Mandelson in 1983. The result of this study was published in 2005 under the title Fightback! Labour’s Traditional Right in the 1970s and 1980s and made the case for a much longer process of modernisation, strongly tied to the trade unions. -

Blue Labour, One-Nation Labour and Postliberalism: a Christian Socialist Reading

1 Blue Labour, One-Nation Labour and Postliberalism: A Christian Socialist Reading John Milbank Within the British Labour party, ‘Blue Labour’ has now been reborn as ‘One- Nation Labour’, after its leader Ed Miliband’s consecration of the phrase. As a mark of this new politics, he and his brother David are now proposing to adopt a ‘living wage’, rather than a mere minimum wage as party policy, in the wake of the successful campaign for the same in London waged by London Citizens. With its overtones of ‘a family wage’ as long backed by Papal social teaching, this flagship policy would seem to symbolise a new combination of economic egalitarianism with (an updated) social conservatism. Such a combination is crucially characteristic of the new ‘postliberal’ politics in the United Kingdom, which seeks to combine greater economic justice with a new role for individual virtue and public honour. But to understand what this new politics means and does not mean, it is necessary to attend closely to the intended sense of both ‘post’ and ‘liberal’. ‘Post’ is different from ‘pre’ and implies not that liberalism is all bad, but that it has inherent limits and problems. ‘Liberal’ may immediately suggest to many an easygoing and optimistic outlook. Yet ‘postliberals’ are by no means invoking a kind of Daily Mail resentment of pleasures out of provincial reach. To the contrary, at the core of its critique of liberalism lies the accusation that it is a far too gloomy political philosophy. How can such a case be made? Well, very simply, liberalism assumes that we are basically self-interested, fearful, greedy and egotistic creatures, unable to see beyond our own selfish needs and instincts. -

DM Newsletter

Rainbow News Issue 3 Rainbow News is published and promoted by members of the ethnic minority community who support David Miliband as the next leader of the Labour Party. David Miliband’s vision for education “Aspiration and excellence for all” Key Dates and Events 1st Septembe r – BALLOT PAPERS ISSUED 25th September - Labour Party Conference ANNOUNCEMENT OF RESULT- Manchester 27th September - Diversity Nite - Manchester NOMINATIONS DEADLINE - 26 July CLP Nominations so for: David Miliband - 71 CLPs Ed Miliband - 53 CLPs Andy Burnham - 20 CLP Diane Abbott -13 CLPs Ed Balls - 6 CLPs Chinese for Labour backs David David with Councillor Mohammed Afzal and the Pakistani High Commissioner in Birmingham last Sunday Today, Chinese for Labour, which represents the needs of the Chinese community in the Labour Last month David delivered a keynote address on his vision for world Party, has come out to back David Miliband for class education. He set out his “brazenly aspirational” goal of im - the Labour Party Leadership. proving standards and widening access to University. He showed his Sonny Leong, Chair of Chinese for Labour says “I commitment to the principle that we invest in our children so they can am pleased that we are backing David for the do better than the generations before them. leadership. David is a friend of China and the Chi - nese community. We have to choose not only the He focused on three areas to deliver a truly outstanding education. leader of our Party but someone to unite the He committed to recruiting at least three-quarters of teachers from Party, oppose and hold to account the coalition the top quarter of graduates because no school is better than the government; command respect on the interna - teachers within it.