Ÿþh P 9 4 C O V E R . J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents Chapter I Chapter Ii

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-62051-3 - English Monasteries A. Hamilton Thompson Table of Contents More information CONTENTS CHAPTER I THE RELIGIOUS ORDERS § 1. The medieval monastery. 2. Growth of monachism in the east. 3. Beginnings of western monachism: Italy, Gaul and Ireland. 4. The rule of St Benedict. 5. The Benedictine order in England: early Saxon monasteries. 6. The Danish invasions and the monastic revival. 7. Monasticism after the Norman conquest. 8. Benedictine abbeys and priories. 9. Priories of alien houses. 10. The Cluniao order. 11. The Carthusian order. 12. The orders of Thiron, Savigny and Grandmont. 13. Founda tion and growth of the Cistercian order. 14. Cistercian monasteries. 15. Monks and conversi. 16. Orders of canons: secular chapters. 17. Augustinian canons. 18. Premonstratensian canons. 19. The order of Sempringham. 20. Nunneries. 21. Decline of the regular orders. The friars. 22. Monastic property: parish churches. 23. Monasteries as land-owners: financial depression. 24. Moral condition of the monasteries. 25. Numbers of inmates of mon asteries. 26. The suppression of the monasteries. 27. Remains and ruins of monastic buildings 1—39 CHAPTER II THE CONVENTUAL CHURCH § 28. Divisions of the monastery precinct: varieties of plan. 29. The plan of church and cloister: necessities governing the church-plan. 30. General arrangement of the church. 31. Eastern arm of the church: Anglo-Norman Benedictine and Cluniac plans. 32. The presbytery and quire. 33. Transept-chapels. 34. Aisled enlargements of the eastern arm. 35. The nave: processional doorways, altars and screens. 36. Parochial use of the nave. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-62051-3 - English Monasteries A. -

Shrewsbury Battlefield Heritage Assessment (Setting) Edp4686 R002a

Shrewsbury Battlefield Heritage Assessment (Setting) Prepared by: The Environmental Dimension Partnership Ltd On behalf of: Shropshire Council October 2018 Report Reference edp4686_r002a Shrewsbury Battlefield Heritage Assessment (Setting) edp4686_r002a Contents Section 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 Section 2 Methodology............................................................................................................... 3 Section 3 Planning Policy Framework .................................................................................... 11 Section 4 The Registered Battlefield and Relevant Heritage Assets ................................... 15 Section 5 Sensitivity Assessment ........................................................................................... 43 Section 6 Conclusions ............................................................................................................. 49 Section 7 Bibliography ............................................................................................................ 53 Appendices Appendix EDP 1 Brief: Shrewsbury Battlefield Heritage Assessment (Setting) – (Wigley, 2017) Appendix EDP 2 Outline Project Design (edp4686_r001) Appendix EDP 3 English Heritage Battlefield Report: Shrewsbury 1403 Appendix EDP 4 Photographic Register Appendix EDP 5 OASIS Data Collection Form Plans Plan EDP 1 Battlefield Location, Extents and Designated Heritage Assets (edp4686_d001a 05 -

Herefordshire News Sheet

CONTENTS PROGRAMME JANUARY-DECEMBER 1994....................................................................... 3 EDITORIAL ........................................................................................................................... 4 MISCELLANY ....................................................................................................................... 5 NOTES ................................................................................................................................. 7 MARTYRDOM OF KING EDMUND .................................................................................... 10 HALESOWEN CASTLE ...................................................................................................... 10 LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETIES AND WEA 16TH ANNUAL DAY SCHOOL ......................... 11 INVESTIGATION IN THE PARISHES OF KENTCHURCH AND ROWLESTONE ............... 12 NEWS FROM THE COUNTY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SERVICE ........................................... 13 FIFTH ANNUAL SHINDIG................................................................................................... 14 FIVE CASTLES IN CLUN LORDSHIP ................................................................................ 17 SOME NOTES ON SWYDD WYNOGION AND TEMPSITER ............................................. 27 CLUN LORDSHIP IN THE 14TH C ....................................................................................... 28 A MOTTE AND BAILEY AND AN ANCIENT CHURCH SITE AT ABERLLYNFI .................. 29 WOOLHOPE CLUB ANNUAL -

Finding Fulbert in Norman England ©

FINDING FULBERT IN NORMAN ENGLAND © John F. Polk, PhD Clan Historian Clan Pollock International Fulbert, the progenitor of the Pollok family of Renfrewshire, is known to us as the father of three individuals, Peter, Robert, and Helya (Elias), who were given feudal fee to the lands of Pollok and who appeared in various 12th century Scottish charters. In this paper the possible origin of this family in Norman England will be explored and a specific individual suggested who may in fact have been Fulbert, progenitor of the Pollok family. Background With one exception, Fulbert himself never appeared directly in a Scottish charter but only indirectly in the form of a patronymic with his sons’ signatures, in Latin,1 i.e. Petrus filius Fulberti, Robertus filius Fuberti, Helia filius Fulberti Helya was a cleric and appointed the Canon of Glasgow cathedral. Peter and Robert were invested with lands in the area of Renfrewshire known as Pollok and took that as their title, giving origin to the family name. Robert was also given lands in Steinton (Stenton), East Lothian. The little we know of these sons of Fulbert comes from the few charters on which their names appeared either as a witness or grantor. All we know of Fulbert from Scottish records is that he was identified as their father. Since the lands of Pollok and Steinton were first given by King David I to Walter FitzAlan, his High Steward, we can conclude that Fulbert’s sons were Walter’s followers, and were given their lands as his vassals under the feudal system that David was instituting in Scotland.2 Because of their association with Walter it has also been generally assumed in Pollok family history that they originated from Shropshire in England, as he did, but this is just speculation. -

Introduction

Introduction By the second quarter of the twelfth century, when Tintern, Whitland and Margam, the first Cistercian abbeys in Wales, were founded, the Anglo- Norman aristocratic élite from which their founders were drawn had succeeded in establishing firm control over lowland Gwent, Glamorgan, Gower and Pembroke, but Whitland and Margam were located on the fringes of these areas in the frontier zones between them and adjoining territory remaining under de facto Welsh rule, and Anglo-Norman governance in these zones was ‘frequently skeletal, nominal or non- existent’1 and constantly being challenged by the Welsh. They were joined in 1147 by the two Welsh Savigniac abbeys, Neath and Basingwerk, which became Cistercian when the Order of Savigny merged with the Cistercian Order. Like Whitland and Margam, Neath was located in a frontier zone, and the Anglo-Norman hold on the area of north-east Wales in which Basingwerk was located was also tenuous by the time it became Cistercian. Following the assumption of the patronage of Whitland and its first daughter-house, Strata Florida, by Rhys ap Gruffudd, the Lord Rhys (d. 1197), after he had succeeded in re-establishing Welsh hegemony in the kingdom of Deheubarth in the 1150s, the filiation of Whitland, which by 1201 numbered a further six Cistercian abbeys distributed throughout the length and breadth of pura Wallia, became clearly identifiable as native Welsh abbeys with Welsh patrons, choir monks and political sympathies, whereas the other Cistercian foundations in Wales all had French or English mother houses and choir monks, maintained close connections with their Anglo-Norman patrons, and were unable to establish Welsh daughter 1 R.R. -

Common Lands and the Quarry’ the Following Text Is an Unrevised Draft Prepared by the Late W

Victoria County History Shropshire Volume VI, part II Shrewsbury: Institutions, buildings and culture Section 3.5, ‘Common lands and the Quarry’ The following text is an unrevised draft prepared by the late W. A. Champion. It is made available here through the kindness of his executors. © The Executors of W. A. Champion. Not to be reproduced without permission. Please send any corrections or additional information to [email protected]. 1 3.5 Common lands and the Quarry. [W.A. Champion – Final draft, Jan. 2012] The agrarian interests of the borough and Shrewsbury abbey By the 1840s almost 3,000 acres of gardens and agricultural land in Shrewsbury’s suburban townships, including Abbey Foregate, still remained to be surveyed by the tithe commissioners, of which half (c.1481 a.) lay in the parish of Holy Cross and St Giles.1 Although to some extent, as elsewhere,2 the open fields at Shrewsbury were once located closest to the built-up areas, with the common pastures further out, that pattern was disturbed not only by the inherent quality of land but also by the sinuous course of the Severn and the disposition of the old river bed abandoned c.5,000 years ago, leaving much of Coton encircled by a belt of damp 'moors'.3 In addition, until 1835 the manor of Meole Brace, including Kingsland common, separated the open fields of Coleham and Frankwell.4 As a result a more irregular pattern existed, notably in Coton where some of the arable open fields lay at the furthest point from the town, separated from it by a mixture of moors and closes. -

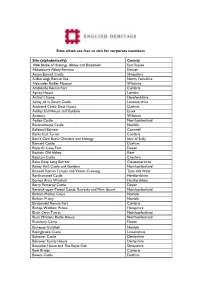

Site (Alphabetically)

Sites which are FREE TO VISIT for Corporate Members Opening times vary, pre-booking may be required, please check English Heritage website for details. Site (alphabetically) County 1066 Battle of Hastings, Abbey and Battlefield East Sussex Abbotsbury Abbey Remains Dorset Acton Burnell Castle Shropshire Aldborough Roman Site North Yorkshire Alexander Keiller Museum Wiltshire Ambleside Roman Fort Cumbria Appuldurcombe House Isle of Wight Apsley House London Arthur's Stone Herefordshire Ashby de la Zouch Castle Leicestershire Auckland Castle Deer House Durham Audley End House and Gardens Essex Avebury Wiltshire Aydon Castle Northumberland Baconsthorpe Castle Norfolk Ballowall Barrow Cornwall Banks East Turret Cumbria Bant's Carn Burial Chamber and Halangy Isles of Scilly Barnard Castle Durham d's Cove Fort Devon Bayham Old Abbey Kent Beeston Castle Cheshire Belas Knap Long Barrow Gloucestershire Belsay Hall, Castle and Gardens Northumberland Benwell Roman Temple and Vallum Crossing Tyne and Wear Berkhamsted Castle Hertfordshire Berney Arms Windmill Hertfordshire Berry Pomeroy Castle Devon Berwick-upon-Tweed Castle, Barracks and Main Guard Northumberland Binham Market Cross Norfolk Binham Priory Norfolk Birdoswald Roman Fort Cumbria Bishop Waltham Palace Hampshire Black Carts Turret Northumberland Black Middens Bastle House Northumberland Blackbury Camp Devon Blackfriars, Gloucester Gloucestershire Blakeney Guildhall Norfolk Bolingbroke Castle Lincolnshire Bolsover Castle Derbyshire Bolsover Cundy House Derbyshire 1 Boscobel House and The -

Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological & Historical Society

Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological & Historical Society Contents Volume 27 part 1 (1904) The Church Bells of Shropshire. II, by H. B. Walters, M.A., F.S.A. Diocese of Hereford, Archdeaconry of Ludlow (continued) The Churchwardens' Accounts of the Parish of Worfield, Part II, 1512-1523, transcribed and edited by H. B. Walters, M.A., F.S.A. Stretton Court Rolls of 1566-7 (A Fragment), transcribed and edited by the Rev. C. H. Drinkwater, M.A. Subsidy Roll for the Hundreds of Purslow and Clun, 1641 Miscellanea Living Descendants of King Henry VII in Shropshire A Letter of the Privy Council to the Magistrates of Salop, anno 1625 Fire Hooks Volume 27 part 2 (1904) The Lords Lieutenant of Shropshire, by W. Phillips, F.L.S. (continued) The Founder and First Trustees of Oswestry Grammar School, by the Hon. Mrs. Bulkeley-Owen A Burgess Roll and a Gild Merchant Roll of 1372, transcribed and edited by the Rev. C. H. Drinkwater, M.A. The Accounts of the Churchwardens of Wem, by the Hon. and Rev. Gilbert H. F. Vane, F.S.A., Rector of Wem The Provosts and Bailiffs of Shrewsbury, by the late Mr. Joseph Morris Miscellanea Memoirs of a Shropshire Cavalier A Recently Discovered Inscription in the Abbey Church, Shrewsbury The Will of Lewys Taylour, Pastor of Moreton Corbet, 1623 Who was the Lady Alice Stury? Did Augustine come to Cressage Volume 27 part 3 (1904) The Lords-Lieutenant of Shropshire, by W. Phillips F.L.S. Manor of Sandford and Woolston, by R. Lloyd Kenyon, M.A. -

English Monasteries A

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-62051-3 - English Monasteries A. Hamilton Thompson Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Manuals of Science and Literature ENGLISH MONASTERIES © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-62051-3 - English Monasteries A. Hamilton Thompson Frontmatter More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-62051-3 - English Monasteries A. Hamilton Thompson Frontmatter More information ST MARY'S ABBEY, YORK. Crossing, north tra.nsept, a.nd north &isle of nave. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-62051-3 - English Monasteries A. Hamilton Thompson Frontmatter More information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-62051-3 - English Monasteries A. Hamilton Thompson Frontmatter More information ENGLISH MONASTERIES BY A. HAMILTON THOMPSON, M.A., F.S.A. Cambridge: at the University Press 19 2 3 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-62051-3 - English Monasteries A. Hamilton Thompson Frontmatter More information cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo, Delhi, Tokyo, Mexico City Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 8ru, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York -

Chapter Three the Households of Royal Illegitimate Family Members and Their Networks of Power

Durham E-Theses Illegitimacy and Power: 12th Century Anglo-Norman and Angevin Illegitimate Family Members within Aristocratic Society TURNER, JAMES How to cite: TURNER, JAMES (2020) Illegitimacy and Power: 12th Century Anglo-Norman and Angevin Illegitimate Family Members within Aristocratic Society, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13464/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Abstract Illegitimacy and Power: 12th Century Anglo-Norman and Angevin Illegitimate Family Members within Aristocratic Society By James Turner The Anglo-Norman and Angevin kings of the twelfth century were supported in the pursuit of their political and hegemonic activities by individual illegitimate members of the royal family. Illegitimate royal family members represented a cadre of auxiliary family members from which Anglo-Norman and Angevin kings, throughout the twelfth century, deployed specific members as a means of advancing their shared interests. -

Names Mentioned More Than Once in a Page Are Indexed Only Once

INDEX Names mentioned more than once in a page are indexed only once. Names of places are printed in italics. ABBEYS. Bardsey Island (Caerns.), Agincourt, battle of, 70, 78, 87, 99, 106; Bourne (Lines.), 98, 106; 127 Bridlington, 104, 106; Bristol, 98, Alcock, Jn, 81 104; Bruton (Som.), 105-6; Burs- Altrincham, 64 cough (Lanes.), 101; Castle Acre, Alvanley, 62, 71 109; Christchurch (London), Anglesey, g, 118, 127 105-6; Cirencester (Glos.), 99, Angouleme, 143 104, 106; Combwell, 99; Darley, Anjou, duke of, 147, 151-2 99, 106; Dorchester (Oxon), 98, Antwerp, 63 106; Dover, 99; Hartland Appleton, Wm, 81, 85 (Devon), 98, 106; Haughmond Aquitaine, 2; duchy of, 10; princi (Salop), 98, 106, 109; Hexham, pality of, 139-160 99; Kenilworth, 105-6; Keyn- Aragon, 62 sham (Som.), 98, 106; Leicester, Arderne, Rob, 62, 71 99, 106; Lemes (Kent), 98, 106; Arley Charters, 65 Lilleshall (Salop), 98, 106; Mis- Armagnac, count of, 140, 147; Jean senden (Bucks), 98, 106; Muchel- de, 141 ney (Som.), log; North Creake Arques, lieutenant of, 74 (Norfolk), 99, 100, 106; Norton, Arrouasian abbeys, 98, 106 97-112; Notley (Bucks), 98, 106; Arundel, earl of, 118, 143 Osney (Oxon), 100, 105-6; O va Aston, family, 83; Sir Ric, 83; Sir st on (Leics.), 98, 106; Rocester Rob, 83 (Staffs.), 99, 106; Runcorn, 98, Attelbrig, Jn, 136 100; St Botolph's, Colchester, 98, Audley, Sir Jas, 16, 145, 149, 151 100, 106; St Frideswide's, Ox Augustine, St, of Hippo, 97 ford, 101, 104, 106; St Helen's Augustinian abbeys 97-112 Derby, 99; St James, Northamp Avignon, court at, 139 -

Site (Alphabetically)

Sites which are free to visit for corporate members Site (alphabetically) County 1066 Battle of Hastings, Abbey and Battlefield East Sussex Abbotsbury Abbey Remains Dorset Acton Burnell Castle Shropshire Aldborough Roman Site North Yorkshire Alexander Keiller Museum Wiltshire Ambleside Roman Fort Cumbria Apsley House London Arthur's Stone Herefordshire Ashby de la Zouch Castle Leicestershire Auckland Castle Deer House Durham Audley End House and Gardens Essex Avebury Wiltshire Aydon Castle Northumberland Baconsthorpe Castle Norfolk Ballowall Barrow Cornwall Banks East Turret Cumbria Bant's Carn Burial Chamber and Halangy Isles of Scilly Barnard Castle Durham Bayard's Cove Fort Devon Bayham Old Abbey Kent Beeston Castle Cheshire Belas Knap Long Barrow Gloucestershire Belsay Hall, Castle and Gardens Northumberland Benwell Roman Temple and Vallum Crossing Tyne and Wear Berkhamsted Castle Hertfordshire Berney Arms Windmill Hertfordshire Berry Pomeroy Castle Devon Berwick-upon-Tweed Castle, Barracks and Main Guard Northumberland Binham Market Cross Norfolk Binham Priory Norfolk Birdoswald Roman Fort Cumbria Bishop Waltham Palace Hampshire Black Carts Turret Northumberland Black Middens Bastle House Northumberland Blackbury Camp Devon Blakeney Guildhall Norfolk Bolingbroke Castle Lincolnshire Bolsover Castle Derbyshire Bolsover Cundy House Derbyshire Boscobel House and The Royal Oak Shropshire Bow Bridge Cumbria Bowes Castle Durham Boxgrove Priory West Sussex Bradford-on-Avon Tithe Barn Wiltshire Bramber Castle West Sussex Bratton Camp and