Common Lands and the Quarry’ the Following Text Is an Unrevised Draft Prepared by the Late W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Six Parishes Newsletter

SIX PARISHES NEWSLETTER for St Giles’ Church. Badger St Milburga’s Church. Beckbury` St Andrew’s Church. Ryton Rector: Rev’d Keith Hodson tel 01952 750774 Email: [email protected] Web Site: www.churches.lichfield.anglican.org/shifnal/beckbury/ Rota of Services in the 6 Parishes – September 2013 Badger Beckbury Ryton Kemberton Stockton Sutton Sunday Maddock 9.30 am 9.30 am 8.15 am 11 am Sept 1st Communion Matins Communion Communion 9.30 am 11 am 11 am Sept 8th Matins Morning Matins 9.30 am Sept 15th Morning 11 am 6.30 pm 11 am Sept 22nd Harvest Evensong Morning 9.30 am 9.30 am 11 am 6.30 pm Sept 29th Matins Communion Harvest Evensong LT Abbreviation: KH = Revd Keith Hodson; TD = Tina Dalton; LT = Local Team; PRAYER OF THE MONTH Father God, we pray for our schools and colleges at the start of the new year. Give to teachers enthusiasm to teach, and give to pupils enthusiasm to learn Especially for those beginning at a new school or university this month. For Jesus sake. Amen Next Newsletter Contributions for next month’s newsletter to either – David Tooth at Havenside, Beckbury – 01952 750324. Email – [email protected] Or Ruth Ferguson at Tarltons, Beckbury – 01952 750267 not later than 14th of this month, please. FROM THE RECTORY Photo Martyn Farnell Dear Friends, I guess that many of us born in the 1950s had summer holidays “at the seaside”. I was brought up in Warwickshire which is about as far from seaside resorts as one can get. -

An Excavation in the Inner Bailey of Shrewsbury Castle

An excavation in the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle Nigel Baker January 2020 An excavation in the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle Nigel Baker BA PhD FSA MCIfA January 2020 A report to the Castle Studies Trust 1. Shrewsbury Castle: the inner bailey excavation in progress, July 2019. North to top. (Shropshire Council) Summary In May and July 2019 a two-phase archaeological investigation of the inner bailey of Shrewsbury Castle took place, supported by a grant from the Castle Studies Trust. A geophysical survey by Tiger Geo used resistivity and ground-penetrating radar to identify a hard surface under the north-west side of the inner bailey lawn and a number of features under the western rampart. A trench excavated across the lawn showed that the hard material was the flattened top of natural glacial deposits, the site having been levelled in the post-medieval period, possibly by Telford in the 1790s. The natural gravel was found to have been cut by a twelve-metre wide ditch around the base of the motte, together with pits and garden features. One pit was of late pre-Conquest date. 1 Introduction Shrewsbury Castle is situated on the isthmus, the neck, of the great loop of the river Severn containing the pre-Conquest borough of Shrewsbury, a situation akin to that of the castles at Durham and Bristol. It was in existence within three years of the Battle of Hastings and in 1069 withstood a siege mounted by local rebels against Norman rule under Edric ‘the Wild’ (Sylvaticus). It is one of the best-preserved Conquest-period shire-town earthwork castles in England, but is also one of the least well known, no excavation having previously taken place within the perimeter of the inner bailey. -

Newsletter No. 51

Page 1 SARPA Newsletter 51 SARPA Newsletter 51 Page 1 Shrewsbury Newsletter Aberystwyth Rail No. 51 Passengers’ August 2010 Association The station with the hump. Aberdovey in the early 1960’s, with No.82033 arriving with a down train. Chairman’s Message..................................................................................................3 News in Brief...............................................................................................................4 When the Computer says No......................................................................................8 AUF WIEDERSEHEN Status Quo............................................................. ...............10 More Cambrian Railways Partnership leaflets..........................................................12 The view from milepost 61 by the Brigadier..............................................................13 Network Rail Reports................................................................................................15 Vale of Rheidol Railway upgrade...............................................................................17 SARPA meetings......................................................................................................18 Websites...................................................................................................................19 Useful addresses......................................................................................................20 Officers of the Association........................................................................................20 -

The Index of Multiple Deprivation 2015

The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2015 is an index calculated from 37 indicators measuring deprivation in its broadest sense. The overall IMD 2015 score combines scores from seven areas (called domains), which are weighted as follows: • Income (22.5%) • Employment (22.5%) • Health and disability (13.5%) • Education, skills and training (13.5%) • Barriers to housing and services (9.3%) • Crime (9.3%) • Living environment (9.3%) Overall in 2015, Shropshire County was a relatively affluent area and was ranked as the 129th most deprived County out of all 149 Counties in England. The IMD is based on sub-electoral ward areas called Lower level Super Output Areas (LSOAs), which were devised in the 2001 Census. Each LSOA is allocated an IMD score, which is weighted on the basis of its population. There were 32,844 LSOAs in England; of these only 9 in Shropshire County fell within the most deprived fifth of all LSOAs in England. These LSOAs were located within the electoral wards of Market Drayton West, Oswestry South, Oswestry West, in North Shropshire; Castlefields and Ditherington, Harlescott, Meole, Monkmoor and Sundorne in Shrewsbury and Ludlow East in South Shropshire. To get a more meaningful local picture, each LSOA in Shropshire County was ranked from 1 (most deprived in Shropshire) to 192 (least deprived in Shropshire). Shropshire LSOAs were then divided into local deprivation quintiles which are used for profiling and monitoring of health and social inequalities in Shropshire County (1 representing the most deprived fifth of local areas and 5 the least). Figure 1 shows the most deprived areas shaded in the darkest colour – these tend to be situated around the major settlements in Shropshire. -

Shifnal Crime

SHIFNAL CRIME Rural Watch – East Shropshire .Rural News from around the Patch A full and thorough investigation is underway following an armed robbery at a bank in Madeley, Telford this afternoon (Monday 20 March) The offence happened at approximately 3pm when a person, entered Lloyd's Bank on the High Street in Madeley. The individual produced what appeared to be a gun, although whether it was real or an imitation gun is unknown, and demanded money before leaving on foot. Nobody was injured in the incident and witnesses and staff have been provided initial support by the investigating officers. The suspect is described as medium build and approximately 5'10" tall. They were dressed all in dark clothing but believed to be wearing black and white trainers. The suspect was carrying a black holdall and they had their face covered during the offence. Superintendent Tom Harding said: "We understand that this crime will be very concerning to the local community and I would reassure you that such a crime is unusual for the Telford area. We will have additional patrols in the Madeley area for the next few days to offer support to the community and identify any further witnesses. I have allocated a significant number of officers to this investigation to ensure we identify and arrest the suspect as soon as possible. To assist us in this I would ask that, as this was a busy time of day in the centre of the town, that anyone who has seen anything suspicious in around the High-Street area this afternoon, or has any other information relating to this serious offence, please call West Mercia Police on 101 quoting incident number 411s of 20 March. -

Lower House Newport, Shropshire

Lower House Newport, Shropshire Lower House Lower Sutton, Newport, Shropshire TF10 8DE A handsome period farmhouse, range of traditional barns with development potential (sub. to PP), in a delightful rural location, set within approx. 4 acres. *AVAILABLE AS A WHOLE OR IN LOTS:* • LOT 1: Spacious 5 bed period farmhouse; tremendous scope with a degree of modernisation to create an excellent family home. • GF farmhouse kitchen; pantry; boot/utility room; living room; dining room; hallway. • FF master bedroom, space for potential en-suite; family bathroom, two further bedrooms. • SF large double bedroom; single bedroom; character sunken floored landing with scope for creating bathroom. • Traditional walled boundary, extensive mature lawned gardens. • LOT 2: Detached traditional brick barns, with separate access and tremendous scope for development sub to p.p. • LOT 3: Approx. 2.62 acres pasture land. • Available as a whole, set in approx. 4 acres (Lots 1, 2 & 3) DISTANCES Newport 4m | Stafford 10m | Telford 15m | Shrewsbury 19m | Birmingham 37m | Manchester 62m Location Located in the attractive and quiet hamlet of Sutton, just 4 miles from the local market town of Newport in Shropshire. Lower House is approached via a peaceful country lane (Guild Lane) and is enclosed to the northern perimeter with traditional red-brick wall boundary and hedging to the east. The property overlooks traditional Shropshire farmland and is located a short distance from the picturesque Aqualate Mere National Nature Reserve. The hamlet of Sutton has a public house, and is adjacent to Forton which offers a further public house, a cricket club and the All Saints Church. -

Copyright Notice

Copyright Notice Crown copyright material is reproduced with the permission of the Controller of HMSO and the Queen's Printer for Scotland All material contained in this document was scanned from an original printed copy of Intercom magazine produced by the Directorate of Telecommunications in January 1975. The licence granted by HMSO to re-publish this document does not extend to using the material for the principal purpose of advertising or promoting a particular product or service, or in a way, which could imply endorsement by a Department, or generally in a manner, which is likely to mislead others. No rights are conferred under the terms of the HMSO Licence to anyone else wishing to publish this material, without first having sought a licence to use such material from HMSO in the first instance. Signed Steven R. Cole 29 th February 2004 \ INTERCOM The Journal of the Home Office Directorate of Telecommunications Number 6 January 1975 INTERCOM The Journal of the Home Office Directorate of Telecommunications Number 6 January 1975 INTERCOIVI is published twice each year by the Directorate and is printed for Her Majesty's Stationery Office by Peridon Ltd, 6 Dalston Gardens, Stanmore, Middlesex HA7 1BJ. No article or any part of an article appearing in it may be reprinted or quoted without permission of the Home Office. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily official views of the Home Office. All enquiries should be directed to the Editor, INTERCOM, Directorate of Telecommunications, 60 Rochester Row, London SW1, England. Telephone Number: 01-828 9848, Extension 739. © Crown Copyright~1975 Contents Communications 74 .......... -

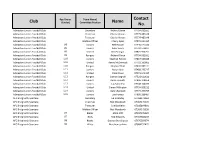

Team and Contact List

Age Group Team Name/ Contact Club Name (Under) Committee Position No. Admaston Juniors Football Club Secretary Richard Owen 07794 932661 Admaston Juniors Football Club Chairman Charlie Viccars 07779 485149 Admaston Juniors Football Club Treasurer Charlie Viccars 07779 485149 Admaston Juniors Football Club Welfare Officer Cherry Syass 07875 521364 Admaston Juniors Football Club U8 Juniors Neil Harper 07446 947335 Admaston Juniors Football Club U9 Juniors Peter Lewis 07794 576877 Admaston Juniors Football Club U9 United Ben Stringer 07825 912251 Admaston Juniors Football Club U9 Rangers Richard Owen 07794 932661 Admaston Juniors Football Club U10 Juniors Stephen Pollock 07817 563665 Admaston Juniors Football Club U10 United Kenny McDermott 07793 160005 Admaston Juniors Football Club U10 Rangers Clayton Elliott 07833 087111 Admaston Juniors Football Club U11 Juniors Aaron Hale 07488 233717 Admaston Juniors Football Club U11 United Dale Oliver 07971 543427 Admaston Juniors Football Club U11 Rangers Damon Bagnall 07521 620610 Admaston Juniors Football Club U12 Juniors Jamie Howells 07496 178659 Admaston Juniors Football Club U13 Juniors Jay Sahadew 07748 144076 Admaston Juniors Football Club U13 United Simon Millington 07734 858212 Admaston Juniors Football Club U14 Juniors Gary Chadwick 07779 299754 Admaston Juniors Football Club U15 Juniors Lee Harvey 07890 388467 AFC Bridgnorth Spartans Secretary Ed Hobbday 07968273163 AFC Bridgnorth Spartans Chairman Rob Woodcock 07984149999 AFC Bridgnorth Spartans Treasurer Sue Boadella 07815804601 AFC Bridgnorth Spartans Welfare Officer Rob Woodcock 07984149999 AFC Bridgnorth Spartans U7 Blacks Mark Clift 07817195029 AFC Bridgnorth Spartans U7 Reds Rob Edwards 07557383259 AFC Bridgnorth Spartans U8 Blacks Duncan Brassington 07970283674 AFC Bridgnorth Spartans U8 White Matthew Jenkins 07884252425 Age Group Team Name/ Contact Club Name (Under) Committee Position No. -

From Maiden and Martyr to Abbess and Saint the Cult of Gwenfrewy at Gwytherin CYCS7010

Gwenfrewy the guiding star of Gwytherin: From maiden and martyr to abbess and saint The cult of Gwenfrewy at Gwytherin CYCS7010 Sally Hallmark 2015 MA Celtic Studies Dissertation/Thesis Department of Welsh University of Wales Trinity Saint David Supervisor: Professor Jane Cartwright 4 B lin a thrwm, heb law na throed, [A man exhausted, weighed down, without hand or A ddaw adreef ar ddeudroed; foot, Bwrw dyffon i’w hafon hi Will come home on his two feet. Bwrw naid ger ei bron, wedi; The man who throws his crutches in her river Byddair, help a ddyry hon, Will leap before her afterwards. Mud a rydd ymadroddion; To the deaf she gives help. Arwyddion Duw ar ddyn dwyn To the dumb she gives speech. Ef ai’r marw’n fyw er morwyn. So that the signs of God might be accomplished, A dead man would depart alive for a girl’s sake.] Stori Gwenfrewi A'i Ffynnon [The Story of St. Winefride and Her Well] Tudur Aled, translated by T.M. Charles-Edwards This blessed virgin lived out her miraculously restored life in this place, and no other. Here she died for the second time and here is buried, and even if my people have neglected her, being human and faulty, yet they always knew that she was here among them, and at a pinch they could rely on her, and for a Welsh saint I thinK that counts for much. A Morbid Taste for Bones Ellis Peters 5 Abstract As the foremost female saint of Wales, Gwenfrewy has inspired much devotion and many paeans to her martyrdom, and the gift of healing she was subsequently able to bestow. -

S519 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

S519 bus time schedule & line map S519 Shrewsbury - Newport View In Website Mode The S519 bus line (Shrewsbury - Newport) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Newport: 2:45 PM - 5:15 PM (2) Shrewsbury: 7:25 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest S519 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next S519 bus arriving. Direction: Newport S519 bus Time Schedule 38 stops Newport Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 2:45 PM - 5:15 PM Bus Station, Shrewsbury Tuesday 2:45 PM - 5:15 PM Post O∆ce, Shrewsbury Wednesday 2:45 PM - 5:15 PM Gasworks, Castle Fields Thursday 2:45 PM - 5:15 PM Social Services O∆ces, Castle Fields Friday 2:45 PM - 5:15 PM St Michael's Terrace, Shrewsbury Saturday Not Operational Flax Mill, Ditherington Spring Gardens, Shrewsbury The Coach Ph, Ditherington S519 bus Info Six Bells Ph, Ditherington Direction: Newport Stops: 38 The Heathgates Ph, Sundorne Trip Duration: 61 min Line Summary: Bus Station, Shrewsbury, Post O∆ce, Albert Road Jct, Sundorne Shrewsbury, Gasworks, Castle Fields, Social Services O∆ces, Castle Fields, Flax Mill, Ditherington, The Coach Ph, Ditherington, Six Bells Ph, Ditherington, Robsons Stores, Sundorne The Heathgates Ph, Sundorne, Albert Road Jct, Sundorne Road, Shrewsbury Sundorne, Robsons Stores, Sundorne, Ta Centre, Sundorne, Sports Village, Sundorne, Featherbed Ta Centre, Sundorne Lane Jct, Sundorne, Junction, U∆ngton, Abbey, U∆ngton, Kennels, Roden, Nurseries, Roden, Hall, Sports Village, Sundorne Roden, Hall, Roden, Talbot Fields, -

Open the 2015 Launch Leaflet

VCH Shropshire England’s greatest local history community project is returning to Shropshire to foster public knowledge, understanding and appreciation of the history and heritage of the county. Shropshire CHESHIRE N DENBIGHSHIRE FLINTSHIRE (detached) Volume XIII S T A F F O R Volume D VI S H Volume VI: Volume 1. Common to St Julian & St Mary, Shrewsbury I R 2. Common to St Alkmond & St Mary, Shrewsbury XII 3. Castle Ward Within & Castle Foregate E St Mary Holy Cross Shrewsbury & St St Borough Julian Giles Volume XI Volume VIII SHROPSHIRE MONTGOMERYSHIRE Volume X Ludlow Borough R A D E N IR O SH RS ER HI ST RE RCE WO HEREFORDSHIRE boroughs volume boundary completed volumes parish boundary miles0 5 volumes in progress indicates detached portion of volume volumes not yet covered by VCH 0 km 8 Map showing the Hundreds and municipal liberties of Shropshire, topographical volumes published and areas of the county where work is yet to begin. CHESHIRE N DENBIGHSHIRE FLINTSHIRE (detached) The Victoria County History The Victoria History of the Counties of England is the English national Volume history. More commonly known as the Victoria County History or XIII simply the VCH, it was founded in 1899 and is without doubt the S T A greatest publishing project in English local history. It has built an F F O international reputation for its scholarly standards. Its aim is to write R Volume D VI S the history of every parish, town and township providing an H Volume VI: Volume 1. Common to St Julian & St Mary, Shrewsbury I R 2. -

Lilleshall Parish Council the Memorial Hall, Hillside, Lilleshall, Shropshire, TF10 9HG

J3/60/2 Lilleshall Parish Council The Memorial Hall, Hillside, Lilleshall, Shropshire, TF10 9HG. Tel: 01952 676379 Email: [email protected] Dear Sir EXAMINATION OF THE TELFORD AND WREKIN LOCAL PLAN 2011-2031 MATTERS, ISSUES & QUESTIONS PAPER Matter – 3 Question 3.2 Is the Local Plan’s settlement hierarchy and proposed distribution of development, particularly between the urban and rural areas, sufficiently justified? With reference to paragraph 28 of the Framework, is adequate provision made for development in rural settlements? I write on behalf of the Lilleshall Parish Council to confirm our support for the statement issued by the Parish & Town Council Group regarding Policy HO10 of the emerging Local Plan. We (the Parish Council) would like to supplement the statement by pointing out that the fundamental aspects of our rural communities are the built and natural environments which combine to provide the intrinsic quality of our landscape. This makes our rural communities what they are. It is therefore impossible to consider the distribution of sustainable development within the rural area, without consideration for the natural environment. The emerging Local Plan provides for sustainable development along with protection of our natural environment through the Policy HO10 in conjunction with the proposals included in Section 6 - Natural environment, where Policy NE7 - Strategic Landscapes is of particular importance. However, Question 6.2 of the Matters challenges the justification of Strategic Landscapes and their consistency with national policy in the Framework. We therefore wish to supplement the statement issued by Parish & Town Council Group with the following points for your consideration. The Lilleshall Parish Council supports the adoption of the Strategic Landscapes, and their purpose to protect the appearance and intrinsic quality of the designated areas.