Program Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brass Chamber Ensembles David Scott, Director Abstract No

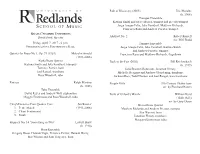

Path of Discovery (2005) Eric Morales (b. 1966) Trumpet Ensemble Katrina Smith and Steve Morics, trumpet and piccolo trumpet Jorge Araujo-Felix, Jake Ferntheil, Matthew Richards, Francisco Razo and Andrew Priester, trumpet Brass Chamber Ensembles David Scott, director Abstract No. 2 Robert Russell Arr. Wiff Rudd Friday, April 7, 2017 - 6 p.m. Trumpet Ensemble Frederick Loewe Performance Hall Jorge Araujo-Felix, Jake Ferntheil, Katrina Smith and Andrew Priester, trumpet Quintet for Brass No.1, Op. 73 (1961) Malcolm Arnold Francisco Razo and Matthew Richards, flugelhorn (1921-2006) Alpha Brass Quintet Back to the Fair (2002) Bill Reichenbach Katrina Smith and Jake Ferntheil, trumpets (b. 1949) Terrence Perrier, horn Julia Broome-Robinson, Jonathan Heruty, Joel Rangel, trombone Michelle Reygoza and Andrew Glendening, trombone Ross Woodzell, tuba Jackson Rice, Todd Thorsen and Joel Rangel, bass trombone Fantasy Ralph Martino Simple Gifts 19th Century Shaker tune (b. 1945) arr. by Eberhard Ramm Tuba Ensemble David Reyes and Andrew Will, euphonium Earle of Oxford’s Marche William Byrd Maggie Eronimous and Ross Woodzell, tuba (1540-1623) arr. by Gary Olson Cinq Miniatures Pour Quatres Cors Jan Kotsier Bravo Brass Quintet 1. Petite March (1911-2006) Matthew Richards and Andrew Priester, trumpet 2. Chant Sentimental Star Wasson, horn 5. Finale Jonathan Heruty, trombone Margaret Eronimous, tuba Frippery No. 14 “Something in Two” Lowell Shaw (b. 1930) Horn Ensemble Gregory Reust, Hannah Vagts, Terrence Perrier, Hannah Henry, Star Wasson and Sam Tragesser, horn Fanfares Liturgiques Henri Tomasi from his London Philharmonic Orchestra days is revealed by his expert i. Annonciation (1901-1971) use of the contrast of tone color and timbre of the brass family in different ii. -

Oboe Trios: an Annotated Bibliography

Oboe Trios: An Annotated Bibliography by Melissa Sassaman A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved November 2014 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Martin Schuring, Chair Elizabeth Buck Amy Holbrook Gary Hill ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2014 ABSTRACT This project is a practical annotated bibliography of original works for oboe trio with the specific instrumentation of two oboes and English horn. Presenting descriptions of 116 readily available oboe trios, this project is intended to promote awareness, accessibility, and performance of compositions within this genre. The annotated bibliography focuses exclusively on original, published works for two oboes and English horn. Unpublished works, arrangements, works that are out of print and not available through interlibrary loan, or works that feature slightly altered instrumentation are not included. Entries in this annotated bibliography are listed alphabetically by the last name of the composer. Each entry includes the dates of the composer and a brief biography, followed by the title of the work, composition date, commission, and dedication of the piece. Also included are the names of publishers, the length of the entire piece in minutes and seconds, and an incipit of the first one to eight measures for each movement of the work. In addition to providing a comprehensive and detailed bibliography of oboe trios, this document traces the history of the oboe trio and includes biographical sketches of each composer cited, allowing readers to place the genre of oboe trios and each individual composition into its historical context. Four appendices at the end include a list of trios arranged alphabetically by composer’s last name, chronologically by the date of composition, and by country of origin and a list of publications of Ludwig van Beethoven's oboe trios from the 1940s and earlier. -

Brock Campbell, Tuba Musical Texture

ANTHONY PLOG Three Miniatures for Tuba and Piano (1990) (b. Glendale, CA, USA, 13 November 1947) Anthony Flog received his music degree from UCLA. Trumpet studies were first with his father (Clifton Flog) and later with Irving Bush, Thomas Stevens, and James Stamp. He has a successful international career as a soloist and has made many recordings. His compositional activities have grown substantially in recent years, and his works are played frequently throughout the world. In 1990 a CD was released which was dedicated to his works for brass {Anthony Plog - Colorsfor Brass with the Summit Brass and the St. Louis Brass Quintet) on Summit Records. Since September 1993 Anthony Plog is In Recital Professor of Music at the Musikhochschule in Freiburg, Germany. Three Miniaturesfor Tuba and Piano was written for tubist Dan Ferantoni. It is intended as a show piece for those characteristics which concert audiences don't normally associate with the tuba, such as virtuoso technical passages and Lyricism in the upper register. Of course, the piece is not simply an exhibition of instrumental capabilities; it is also an ensemble piece for tuba and piano, with both instruments weaving in and out of the Brock Campbell, tuba musical texture. The first and third movements (both Allegro vivace) are aggressive in style, while the second movement (Freely) is calm and reflective. Candidate for the Master of Music degree in Applied Music ELIZABETH RAUM Concerto del Garda (1996) (b. Berlin, NH, USA, 13 January 1945) assisted by Elizabeth Raum is active both as an oboist and as a composer. She earned her Bachelor of Music in oboe performance from the Eastman School of Music in 1966 and her Master Roger Admiral, piano of Music in composition from the University of Regina in 1985. -

Dissertation Document

Three Dissertation Recitals of Trombone Music by John William Gruber A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Performance) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor David Jackson, Chair Professor Colleen Conway Professor Michael Haithcock Professor Fritz Kaenzig Professor Edward Norton John William Gruber [email protected] Ó John William Gruber 2018 Table Of Contents ABSTRACT iii First Recital Program 1 Program Notes 2 Second Recital Program 7 Program Notes 8 Third Recital Program 13 Program Notes 14 ii Abstract Three trombone recitals given in lieu of a written dissertation for the degree A. Mus. D. in performance. Saturday, September 30, 2017, Hankinson Rehearsal Hall, Moore Building, University of Michigan. Liz Ames, piano; Becky Bloomer and Ben Thauland, trumpets; Morgan LaMonica, horn; Phillip Bloomer, tuba; Colleen Bernstein, Danielle Gonzalez and Alec Ockaskis, percussion; Elliott Tackitt, conductor. Fantasy for Trombone, by Malcolm Arnold; Harvest: Concerto for Trombone, by John Mackey; Hommage A Bach, by Eugene Bozza; Romance, by William Grant Still; Suite for Brass Quintet, by Herbert Haufrecht. Monday, December 11, 2017, Stamps Auditorium, Walgreen Drama Center, University of Michigan. Liz Ames, piano; Rhianna Nissen, mezzo-soprano; Joel Trisel, baritone. “Almo Factori” from Motetto de Tempori, by František Ignác Antonín Tuma; Cinque canti all’antica, by Ottorino Respighi; Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, by Gustav Mahler; Basta, by Folke Rabe; Vocalise Etude, but Olivier Messiaen; Cançao de Cristal, by Heitor Villa-Lobos; “Vocalise” from Fourteen Songs, op. 34, by Sergei Rachmaninoff; What Will Be, Will Be Well, by Andrew Selle. -

Jan Koetsier

Jan Koetsier Jan Koetsier was born on 14 August 1911 in Amsterdam, the son of the singer Jeanne Koetsier and the teacher Jan Koetsier-Muller. From an early age he received musical encouragement and support (piano lessons). Koetsier decided to study music early on, entering college straight after leaving school. He moved to Berlin in 1913 with his family, and aged 16, was the youngest student of his day to pass the entrance audition in piano to the Berlin Hochschule für Musik. There, as well as studying piano, he studied score- reading and music theory with Walther Gmeindl, and conducting with Julius Prüwer from 1932. Also encouraged by Artur Schnabel, signs of his future direction in music began to emerge – composing and conducting. In 1933, Koetsier took up a position as a répétiteur at the Stadttheater in Lübeck. But after just one concert season, he returned to Berlin and began working as a conductor touring with theatre ensembles such as the ‘Deutsche Musikbühne’ and the ‘Deutsche Landesbühne’; his repertoire expanded to include music theatre works. From 1936/37 he had the opportunity of working as a freelance conductor for the short-wave broadcasting station in Berlin, directing broadcasts of his own folk music arrangements, including arrangements of South American and African songs. Because of the political situation, Koetsier gave up his position at the Berlin radio station in 1940 and took up an offer of working as piano accompanist to the dancer Ilse Meudtner on a year-long tour. Following on from this, he worked as conductor of the newly-founded Kammeropera in The Hague, during which he travelled to numerous Dutch towns and cities (1941/42). -

Woman to Woman Woman to Woman

Woman to Woman Woman to Woman Thursday Scholarship Series Bonus Concert Thursday March 29 2018 • 7:30 p.m. INTERMISSION PROGRAM Welcome Jean Ngoya Kidula A Play on Atsia and Kpanlogo Grooves Monica Corliss Lilli Boulanger (1893-1918) D’un Matin de Printemps Wesley Hamilton Arr. Charles Young Malik Henry The Yargo Trio Jennifer Larue Angela Jones-Reus, flute Claudia Malchow Connie Frigo, saxophone Jamie Mancuso Liza Stepanova, piano Helen Hopekirk (1856-1945) The Winter It Is Past Augusta Read Thomas (Born 1964) Silhouettes for Solo Marimba Alissa Benkoski, soprano Taylor Lents, marimba Vivian Doublestein, piano Rebecca Clarke (1886-1979) Lullaby and Grotesque Melina Wagner Noggin: Lush Light Maggie Snyder, viola Martha Thomas, piano Amy Pollard, bassoon Martha von Sabinin (1831-1892) Acht Lieder (Born 1950) (Commissioned 2017) Libby Larson Stunned Nr. 1 O wär ich ein Stern (Jean Paul) Maggie Snyder, viola Nr. 5 Lied (Julius Sturm) Sharon J Willis (Commissioned 2017) Dance Elizabeth Knight, mezzo soprano Kathryn Wright, piano IV Waterfall Ballet Monica Hargrave, harp Nicole Chamberlain (Born 1977) The Blue Plate 1. Chakalaka Jan Koetsier (Born 1911) Sonata fur Horn und Harfe, Op. 94 2. Sata Andagi II. Larghetto 3. Grits Jean Martin-Williams, horn The Kitchen Sync Monica Hargrave, harp Catherine Kilroe-Smith, horn Emily Koh (Born 1986) Logos Akiko Iguchi, piano Katherine Emeneth, flute Serena Schibelli, violin Margaret Synder, viola Emily Koh, bass Closing Remarks HODGSON CONCERT HALL 32 Performance UGA March April 2018 33 Woman to Woman About the Soloists Alissa Benkoski (soprano) is a freshman at UGA in Music Education. She has studied Monica Hargrave is the Professor of Harp Studies at UGA. -

The Dutch Tuba:The Solo Tuba Works of Jan Koetsier

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Music Programs Music 4-20-2004 The Dutch Tuba:The Solo Tuba Works of Jan Koetsier Michael Forbes Tuba Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Forbes, Michael Tuba, "The Dutch Tuba:The Solo Tuba Works of Jan Koetsier" (2004). School of Music Programs. 2661. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp/2661 This Concert Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 111-mo1s- 5 tate Ll n1vers1- 't _y l 5chool of Music I I I THE DUTCH TLl5A: The Solo Tuba Works of Jan Koetsier I Michael Forbes, Tuba with I The Illinois State Llniversit_:1 Chamber Orchestra & the Illinois State Graduate Tuba Quartet I with additional guests: Michelle Vought, Soprano I And Karen Callier, V,'o/,'n & fiano I I I I Center tor the Fertorming Arts April 20, 2oo+ T uesda~ E_vening I 8:00p,m. This is the one hundred and titt~-tirst program ot the 200,-2001· season. I I I frogram Translation tor Galgenlieder provided b~ Maria 5taeblein All Worb b_yJan Koetsier(bom 1911) I I .Gallows-Songs• The E)irth-Song Concertino, Op. (1978) 77 A little child is filling its little diapers today. But around the house, oh horrors, mean winds are Allegro con brio I I blowing. -

Program Notes by Leonard Garrison 7:30 P.M., Saturday, June 6, 2015 Sonata for Horn and Piano, Op. 347 Fritz Spindler [Note by C

Program Notes by Leonard Garrison 7:30 p.m., Saturday, June 6, 2015 Sonata for Horn and Piano, Op. 347 Fritz Spindler [Note by Chris Dickey] Fritz Spindler (1817-1905) was a German composer and pianist. He originally studied to become a minister but later realized his passion was for music. After years of studying piano privately, Spindler dedicated his life to composition and teaching. During his lifetime, he was productive and wrote in various genres, including trios, sonatas, opera transcriptions, two symphonies, a piano concerto, orchestral works, and numerous teaching pieces for the piano. His compositions are noted for their tuneful melodies and artful construction. This Sonata for Horn and Piano, Op. 347 is no exception. The first movement expresses a traditional sonata-allegro form, but the music travels to unexpected tonal centers in all three formal areas of the movement. An aria-like middle movement follows and features long, fluid melodic lines for the soloist and pianist. The lively finale is a spirited rondo that brings the sonata to a conclusion. In general, the piano part is especially virtuosic as Spindler himself was a gifted pianist. Sonata for Cello Solo in C Minor, Op. 28 Eugène Ysaÿe Belgian violinist, composer, and conductor Eugène Ysaÿe (1858-1931) studied with his father and Henri Vieuxtemps. He taught a generation of famous violinists at the Brussels Conservatory, including Joseph Gingold, Nathan Milstein, and violist Willian Primrose. Many of the leading composers of the time dedicated works to him, most notably César Franck’s Violin Sonata. Ysaÿe’s best-known compositions are his six solo sonatas for violin, and the Cello Sonata makes equal demands of virtuosity. -

The Modern Bass Trombone Repertoire: an Annotated List and Pedagogical Guide

THE MODERN BASS TROMBONE REPERTOIRE: AN ANNOTATED LIST AND PEDAGOGICAL GUIDE by Evan J. Conroy Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2018 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee: __________________________________________ Richard Seraphinoff, Research Director __________________________________________ Peter Ellefson, Chair __________________________________________ Carl Lenthe __________________________________________ Peter Miksza November 05, 2018 ii To Tatiana; I could have never done this without you. iii Acknowledgements I’d like to thank all of those who have encouraged me to finish this degree in a timely manner. To my wife, Tatiana, who has been a constant source of strength and support. To my family and friends who have held a constant interest in my progress and have made numerous suggestions throughout my journey through higher education. To Alex Lowe, who has graciously housed me during my stays in Bloomington after moving back to Louisiana. To my teachers, especially Pete Ellefson, who have inspired and motivated me to be my best. iv The Modern Bass Trombone Repertoire: An Annotated List and Pedagogical Guide Since the last edition of Thomas Everett’s book, An Annotated Guide to the Bass Trombone, the bass trombone literature has gone largely undocumented in one source for professionals, teachers, and students as a reference for the expanding repertoire. While this document does not fully update the repertoire list, it does provide a representative sampling of the works written for the instrument since 1985. -

Music and Liturgical Arts Ministries of Ann Arbor First United Methodist Church

An amazing venue of performances to delight all ages presented by: Music and Liturgical Arts Ministries of Ann Arbor First United Methodist Church Downtown: 120 South State Street, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104 Northeast: 1001 Green Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48105 (734) 662-4536 • www.fumc-a2.org to the Ann Arbor First Music and Arts Series at First United Methodist Church of Ann Arbor! We are pleased to once again present a rich array of Music and Arts offerings for the 2015-2016 season. Continuing with our central goal – there is something to appeal to audiences of all ages, backgrounds and musical tastes: classic choral offerings, dazzling organ repertoire, chamber music, global music, Broadway show tunes, holiday favorites and contemporary, folk, gospel, and jazz music. We look forward to seeing you in the months ahead! Ann Marie Koukios Ted Brokaw Minister of Music Music and Liturgical Arts Forum Chair 120 South State Street First Music and Arts Series Ann Arbor, MI 48104 SEPTEMBER Adam Unsworth in Concert 27, 2015 SATURDAY A Music Ministries Benefit Concert 3:00pm Adam Unsworth, horn Naki Sung Kripfgans, organ & piano We are pleased to welcome guest artist Adam Unsworth to open our 2015-2016 Downtown Series this fall. Soloist and recording artist Adam Unsworth is Associate Professor of Horn at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. As a performer he is dedicated to commissioning and performing works of living composers, with a goal of expanding repertoire and redefining the boundaries of the horn. His recent CD release, Snapshots, on Equilibrium Records, is Adam Unsworth, horn a compilation of previously unrecorded music, much of which Adam commissioned since starting at Michigan in 2007. -

Three Dissertation Recitals of Euphonium and Tuba Music By

Three Dissertation Recitals of Euphonium and Tuba Music by Angel Elizondo Garza A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Performance) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Fritz A. Kaenzig, Chair Professor Colleen M. Conway Associate Professor Daniel Gilbert Professor Joel D. Howell Professor David Jackson Angel Elizondo Garza [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-9054-2422 © Angel Elizondo Garza 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES iii ABSTRACT iv RECITAL 1 1 Recital 1 Program 1 Recital 1 Program Notes 2 RECITAL 2 9 Recital 2 Program 9 Recital 2 Program Notes 10 RECITAL 3 16 Recital 3 Program 16 Recital 3 Program Notes 17 ii LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1.1 Portrait of Roger Kellaway 2 1.2 Portrait of Richard Strauss by Max Lieberman 3 1.3 Portrait of Áron Romhányi 4 1.4 Portrait of Modest Mussorgsky by Ilya Repin 5 1.5 Portrait of Grigoras Dinicu 8 2.1 Portrait of Amilcare Ponchielli 10 2.2 Portrait of Paul Hindemith 11 2.3 Portrait of William Kraft 12 2.4 Portrait of Astor Piazzolla & his bandoneon 13 2.5 Portrait of Oskar Böhme 14 3.1 Portrait of Libby Larsen 17 3.2 Portrait of Robert Schuman 18 3.3 Portrait of Jan Koetsier 19 3.4 Portrait of Oliver Messiaen 20 3.5 Portrait of David Gillingham 21 iii ABSTRACT SUMMARY OF DISSERTATION RECITALS THREE DISSERTATION RECITALS OF EUPHONIUM AND TUBA MUSIC By Angel Elizondo Garza Chair: Fritz A. -

Records Crystal

®CRYSTAL RECORDS 2012 COMPACT DISC CATALOG 3DKD@RDRMDVSNSGHRB@S@KNF@QDRGNVMNMSGHRO@FD See inside for these and over 270 other fabulous CDs CD662, page 15 CD769, page 13 CD272, page 12 CD251, page 10 CD823, page 4 CD221, page 19 CD839, page 22 CD949, page 7 CD970, page 7 :D@QRNE3DBNQCHMF&WBDKKDMBD “Hats off to a label that chases the new, the exciting, the overlooked, and the orphaned.” – Music Web Flute pg. 2 Horn pg. 15 Accordion, Harp, Organ, Hovhaness pg. 24 Oboe pg. 3 Trombone pg. 17 Guitar, Percussion pg. 23 Verdehr Trio pg. 6 Clarinet pg. 5 Tuba pg. 17 Woodwind Quintets pg. 10 Reicha Quintets pg. 11 Bassoon pg.7 Violin pg. 20 Brass Quintets pg. 19 Genesis CDs pg. 26 Saxophone pg. 9 Viola pg. 21 Misc. Orchestra pg. 23 Order information, Trumpet pg. 13 Cello & Bass pg. 22 Sousa Band pg. 24 see pg. 27 FREE COMPACT DISC See coupon offer on page 27 Sound Samples and New Releases at www.crystalrecords.com email: [email protected] COMPACT DISCS – Titles shown in red are new to this catalog. CDs are $16.95 each. Orders may be placed by mail, phone, fax, email, or online at www.crystalrecords. com. Order information is on page 27. Phone: 360-834-7022, email: [email protected]. FLUTE and PICCOLO CDS — LEONE BUYSE, FLUTE. Buyse was solo flute with Boston Symphony; now at Rice Univ. “Solid playing, glistening recording” Fanfare. She has six CDs: CD317: The Sky’s the Limit. Barber, Canzone (flute, piano); Dahl, Variations on a Swedish Folk Tune (flute, alto flute); John Cage, Three Pieces for Flute Duet; Martin Amlin, Sonata(flute, piano); Antoniou, Lament for Michele (solo flute); Juli Nunlist, 12 Bagatelles (solo flute); Gregory Tucker, Idle Conversation (two flutes); Vivian Fine, The Flicker (solo flute), and Emily’s Images (flute, piano), with Martin Amlin, piano; Fenwick Smith, flute & alto flute.