Book-90925.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis Papers the Real Wild West Writings

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis papers The Real Wild West Rev. July 2013 Writings 1:1 Typed draft book proposals, overviews and chapter summaries, prologue, introduction, chronologies, all in several versions. Letter from Wallis to Robert Weil (St. Martin’s Press) in reference to Wallis’s reasons for writing the book. 24 Feb 1990. 1:2 Version 1A: “The Making of the West: From Sagebrush to Silverscreen.” 19p. 1:3 Version 1B, 28p. 1:4 Version 1C, 75p. 1:5 Version 2A, 37p. 1:6 Version 2B, 56p. 1:7 Version 2C, marked as final draft, circa 12 Dec 1990. 56p. 1:8 Version 3A: “The Making of the West: From Sagebrush to Silverscreen. The Story of the Miller Brothers’ 101 Ranch Empire…” 55p. 1:9 Version 3B, 46p. 1:10 Version 4: “The Read Wild West. Saturday’s Heroes: From Sagebrush to Silverscreen.” 37p. 1:11 Version 5: “The Real Wild West: The Story of the 101 Ranch.” 8p. 1:12 Version 6A: “The Real Wild West: The Story of the Miller Brothers and the 101 Ranch.” 25p. 1:13 Version 6B, 4p. 1:14 Version 6C, 26p. 1:15 Typed draft list of sidebars and songs, 2p. Another list of proposed titles of sidebars and songs, 6p. 1:16 Introduction, a different version from the one used in Version 1 draft of text, 5p. 1:17 Version 1: “The Hundred and 101. The True Story of the Men and Women Who Created ‘The Real Wild West.’” Early typed draft text with handwritten revisions and notations. Includes title page, Dedication, Epigraph, with text and accompanying portraits and references. -

The Annals of Iowa for Their Critiques

The Annals of Volume 66, Numbers 3 & 4 Iowa Summer/Fall 2007 A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF HISTORY In This Issue J. L. ANDERSON analyzes the letters written between Civil War soldiers and their farm wives on the home front. In those letters, absent husbands provided advice, but the wives became managers and diplomats who negotiated relationships with kin and neighbors to provision and shelter their families and to preserve their farms. J. L. Anderson is assistant professor of history and assistant director of the Center for Public History at the University of West Georgia. DAVID BRODNAX SR. provides the first detailed description of the role of Iowa’s African American regiment, the 60th United States Colored Infantry, in the American Civil War and in the struggle for black suffrage after the war. David Brodnax Sr. is associate professor of history at Trinity Christian College in Palos Heights, Illinois. TIMOTHY B. SMITH describes David B. Henderson’s role in securing legislation to preserve Civil War battlefields during the golden age of battlefield preservation in the 1890s. Timothy B. Smith, a veteran of the National Park Service, now teaches at the University of Tennessee at Martin. Front Cover Milton Howard (seated, left) was born in Muscatine County in 1845, kidnapped along with his family in 1852, and sold into slavery in the South. After escaping from his Alabama master during the Civil War, he made his way north and later fought for three years in the 60th U.S. Colored Infantry. For more on Iowa’s African American regiment in the Civil War, see David Brodnax Sr.’s article in this issue. -

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

The Imagined West

CHAPTER 21 The Imagined West FOR more than a century the American West has been the most strongly imagined section of the United States. The West of Anglo American pioneers and Indians began reimagining itself before the conquest of the area was fully complete. In the late nineteenth century, Sitting Bull and Indians who would later fight at Wounded Knee toured Europe and the United States with Buffalo Bill in his Wild West shows. They etched vivid images of Indian fights and buffalo hunts into the imaginations of hundreds of thousands of people. The ceremonials of the Pueblos became tourist attractions even while the Bureau of Indian Affairs and missionaries struggled to abolish them. Stories about the West evolved into a particular genre, the Western, which first as novels and later as films became a defining element of American popular culture. By 1958, Westerns comprised about 11 percent of all works of fiction pubHshed in the United States, and Hollywood turned out a Western movie every week. In 1959 thirty prime-time television shows, induding eight of the ten most watched, were Westerns. Mid-twentieth-century Americans consumed such enormous quantities of imagined adventures set in the West that one might suspect the decline of the Western in the 1970s and 1980s resulted from nothing more than a severe case of cultural indigestion. This gluttonous consumption of fictions about the West is, however, only part of the story. Americans have also actively imagined their own Wests. A century of American children grew up imagining themselves to be cowboys and Indians. -

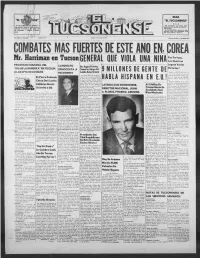

Combates Mas Fuertes De Este Ano En, Corea

í P í READ EL T "EL TUCSONENSE" : El máa antlfn "ii Tha Southwesr and finest News- Con notlolaa hut d otitmb Vminuto; paper printed In Spanish, Is published y. artículos de tn lereA i m turna por Semi-Weekl- I unificación y iriaUd yaiftmeri- - EL TUCSONENSE Is delcated to an unity and friendships up-t- o data, with articles of interest. Ano XXXVI Númer0 134 Viernes, 13 de Junio de 1952 VL Números del nía 5c Atrasados Ule COMBATES MAS FUERTES DE ESTE ANO EN, COREA Mr. Harriman Tucson GENERAL QUE VIOLA UNA NINA Por Fortuna, en Los Nuestros PROGRAMA MAÑANA, DEL Logran Varías CANDIDATO En Agua Prieta, Victorias ! 'DIA DE LA BANDERA" EN TUCSON DEMOCRATA A Sonora, Huye Al 9 MILLONES DE GENTE DE A LAS 8 DE LOS ELKS SEOUL, PM, PRESIDENTE Lado Americano Corea, Viernes Junio 13 Toda esta semana, de día y de En prensa diaria de Nogales, noche, lia hab.do mas fuertes com-oat- es En Paseo Redondo se dan los detalles completos, HADLA en Corea que en cualesqui- el lúnes de esta semana, acerca HISPANA EN era otro periodo E.U.! similar de esta Del de quo el General Alberto Ortega año. Cerco Centro y Ortega, que venia actuando en Furiosos combates en el frente Agua Prieta, Sonora, como Jefe de central al suroeste de Kimsong, los Admisión Gratis Policía, 'huyó al lado americano LATINOS CON EISENHOWER, A 15 Millas De aliados con lanza-llam- arroja- tras de violar a un niña de menos ron a cientos de norcoreanos y catorce años Se Invita a Ud. -

Edmond Visual Arts Commission Album of Art Pieces

Public Art Presented by Edmond Visual Arts Commission and Edmond Convention and Visitors Bureau SINCE ART IN PUBLIC PLACES ORDINANCE IN EDMOND, OKLAHOMA Edmond Visual Arts Commission Partnered Pieces Before EVAC, Gifted, or CIP Funded Pieces Privately Owned Art Pieces for Display only Above it All by Sandy Scott Broadway & Main African Sunset by Jeff Laing Covel median east of Kelly Ancient One by Gino Miles Route 66, east of Douglas, Sugar Hill Entry Ancient One by Jimmie Dobson Jr. Boulevard median, south of Edwards Angelic Being by David Pearson 1601 S Kelly Ave, First Commercial Bank Anglers by Jane DeDecker 3540 S Boulevard Angles by Jim Stewart Boulevard median, at Hurd Street Arc of Peace by Lorri Acott Hafer Park, by the Duck Pond and Iris Garden At the Dance by Dean Imel Danforth, south side at Washington Backyard Adventure by Missy Vandable 906 N Boulevard, OK Christian Home Balance by Destiny Allison Boulevard median between Main & Hurd Belly Dancer by Joshua Tobey Kelly Ave & 33rd, OnCue Best Friends by Gary Alsum Mitch Park by Disc Golf Park Big Wish by Linda Prokop Hafer Park Biomagnestizm by Mark Leichliter Main & Littler, south east corner Blue Hippo Kitsch Art 1129 S Broadway, AAA Glass & Mirror Breath by David Thummel University of Central Oklahoma The Broncho by Harold Holden University of Central Oklahoma Broncho Mural “The Land Run of 1889” by Dr. Bob Palmer and Donna Sadager University of Central Oklahoma Centennial Clock 2nd Street & Broadway Chauncey by Jim Budish 19 N Broadway, Shadid & Schaus Office Building Cloned Cube by Joe Slack Boulevard median, north of Wayne Cobra Lilies by Tony Hochstetler Broadway & 1st Street, north west corner Color Crazy Swirl by Andrew Carson 104 S Broadway Come Unto Me by Rosalind Cook 15 S Broadway Commerce Corner by Dr. -

December 2015

Vol. 46, No. 12 Published monthly by the Oklahoma Historical Society, serving since 1893 December 2015 Holiday festivities at the Murrell Home to host Christmas Frank Phillips Home Open House The Frank Phillips Home in Bartlesville will host an afternoon The George M. Murrell Home full of holiday festivities on Sunday, December 13, beginning in Park Hill will host its fifteenth at 2 p.m. Activities will include tours of Santa’s Cottage, the annual Christmas Open House Santa Walk, and a free outdoor concert. For the enjoyment of on Sunday, December 13, from guests, the home’s interior has been beautifully decorated with 1 to 4 p.m. Visitors are invited to festive floral arrangements, Christmas trees, and wreaths. tour the 1845 mansion and learn On December 13, from 2 to 4 p.m., the Frank Phillips Home about Christmas customs from and the Jane Phillips Society invite parents and children to the mid-Victorian period. The Santa’s Cottage, located just to the south of the mansion. halls will be decked in Christmas Reenactors Brandon and Rachael Reid portray Santa Claus fashions of the 1800s, and live and Mrs. Claus, and will visit with children of all ages. Jane music will fill the air. Each room Phillips Society volunteers will serve homemade cookies and in the home will have a unique punch. All are welcome at Santa’s Cottage, a free event. Victorian Christmas theme. The Also on December 13, from 2 to 4 p.m., the Santa Walk will Friends of the Murrell Home will provide fun for all ages. -

Oklahoma Territory Inventory

Shirley Papers 180 Research Materials, General Reference, Oklahoma Territory Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials General Reference Oklahoma Territory 251 1 West of Hell’s Fringe 2 Oklahoma 3 Foreword 4 Bugles and Carbines 5 The Crack of a Gun – A Great State is Born 6-8 Crack of a Gun 252 1-2 Crack of a Gun 3 Provisional Government, Guthrie 4 Hell’s Fringe 5 “Sooners” and “Soonerism” – A Bloody Land 6 US Marshals in Oklahoma (1889-1892) 7 Deputies under Colonel William C. Jones and Richard L. walker, US marshals for judicial district of Kansas at Wichita (1889-1890) 8 Payne, Ransom (deputy marshal) 9 Federal marshal activity (Lurty Administration: May 1890 – August 1890) 10 Grimes, William C. (US Marshal, OT – August 1890-May 1893) 11 Federal marshal activity (Grimes Administration: August 1890 – May 1893) 253 1 Cleaver, Harvey Milton (deputy US marshal) 2 Thornton, George E. (deputy US marshal) 3 Speed, Horace (US attorney, Oklahoma Territory) 4 Green, Judge Edward B. 5 Administration of Governor George W. Steele (1890-1891) 6 Martin, Robert (first secretary of OT) 7 Administration of Governor Abraham J. Seay (1892-1893) 8 Burford, Judge John H. 9 Oklahoma Territorial Militia (organized in 1890) 10 Judicial history of Oklahoma Territory (1890-1907) 11 Politics in Oklahoma Territory (1890-1907) 12 Guthrie 13 Logan County, Oklahoma Territory 254 1 Logan County criminal cases 2 Dyer, Colonel D.B. (first mayor of Guthrie) 3 Settlement of Guthrie and provisional government 1889 4 Land and lot contests 5 City government (after -

Acting for the Camera: Horace Poolaw's Film Stills of Family, 1925

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Spring 2011 ACTING FOR THE CAMERA HORACE POOLAW'S FILM STILLS OF FAMILY, 1925-1950 Hadley Jerman University of Oklahoma Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the American Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Jerman, Hadley, "ACTING FOR THE CAMERA HORACE POOLAW'S FILM STILLS OF FAMILY, 1925-1950" (2011). Great Plains Quarterly. 2684. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2684 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ACTING FOR THE CAMERA HORACE POOLAW'S FILM STILLS OF FAMILY, 1925-1950 HADLEY JERMAN [Prior to the invention of the camera], one [viewed oneself as if before a] mirror and produced the biographical portrait and the introspective biography. [Today], one poses for the camera, or still more, one acts for the motion picture. -Lewis Mumford, Technics and Civilization (1934) During the late 1920s, American technology making dramatically posed, narrative-rich historian Lewis Mumford drafted these words portraits of family members, Mumford asserted in a manuscript that would become Technics that the modern individual now viewed him or and Civilization. At the same time, Kiowa pho herself "as a public character, being watched" by tographer Horace Poolaw began documenting others. He further suggested that humankind daily life in southwestern Oklahoma with the developed a "camera-eye" way of looking at very technology Mumford alleged altered the the world and at oneself as if continuously on way humanity saw itself. -

Unpublished History of the United States Marshals Service (USMS), 1977

Description of document: Unpublished History of the United States Marshals Service (USMS), 1977 Requested date: 2019 Release date: 26-March-2021 Posted date: 12-April-2021 Source of document: FOIA/PA Officer Office of General Counsel, CG-3, 15th Floor Washington, DC 20350-0001 Main: (703) 740-3943 Fax: (703) 740-3979 Email: [email protected] The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. U.S. Department of Justice United States Marshals Service Office of General Counsel CG-3, 15th Floor Washington, DC 20530-0001 March 26, 2021 Re: Freedom of Information Act Request No. -

Bring Us Al Jennings Again, Just for Tonight!

Masked Bandits Rob Pullman Passengers On Katy Special 'HOME E AP-DMOREIT-E EDITION DAILY EDIT In Z -T- hrift-Progress & FULL LEASED WIRE ASSOCIATED PRESS ARDMC OKLAHOMA, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 23, 1921. VOL. 28. NO. 138. TEN PAGES Backward, Turn Backward, Oh Time In Your Flight; Bring Us Al Jennings Again, Just For Tonight! FIRST WOMEN IN THE NATIONAL PUBLIC BOMB FROM DEFENSE IN THE EYE CLARA FORCED FROM 'PAGE BP. IMPEACHMENT Mrs. Calvin Coolidje ' TRAPP PROCEEDINGS m,. chajle5 Evans Hughes Will Haves WHEN 'KNIGHTS OF THE ROAD'STAGE IS O0D'; COURT OVERRULES MOTION mm WILD AND WODLY WESTERN ROBBERY TO QUASH; SUSTAINED ON DIVISION sr,ji ON FLYING CRACK TRAIN ON o liJJL 1 r Presiding Justice Prevents y LEGISLATORS TIRE OF & "L Passengers Relieved of MUNICIPAL COURT FIXES Over Introduction Evidence to WHITE LIGHTS AT $2 PER vuMMAMA'.tiVl1.1 US I V WA K IV I M1NLMUM CASH BOND r 91 U i J Thousand Dollars After When per Show Party Caucus Had the diem reached the Ernest Ford and Cecil Byrd, who lonely mark of two dollars per Corn Liquor Supplied . p were arrested yesterday rourning Instituted Frame-U- rtiem, Oklahoma r? begin A- 1 S S X H f I IS . J i 8 charged with assaulting Policeman to white-wa- y Bandits With Nerve tiro of tha and thu Jackson on East Main street, and fhort skirts and '.ong to return tJ who put up bonds of '0 each to MAY quietude RECONSIDER the of the pastoral lifo. Insure their appearance when their They to sct back WILL GANG LEADER want to tie farm case was called In municipal court, VOTE OF SENATORS wl'ero they may , unsliMuroed - failed to appear at morning to 'hogs Ij?- this GO INTO THE MOVIES?- - tho iu they choic;) the bonds were de- corn sesalon and their FATE OF STATE OFFICER WILL and alfalfa. -

Ally, the Okla- Homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: a History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989)

Oklahoma History 750 The following information was excerpted from the work of Arrell Morgan Gibson, specifically, The Okla- homa Story, (University of Oklahoma Press 1978), and Oklahoma: A History of Five Centuries (University of Oklahoma Press 1989). Oklahoma: A History of the Sooner State (University of Oklahoma Press 1964) by Edwin C. McReynolds was also used, along with Muriel Wright’s A Guide to the Indian Tribes of Oklahoma (University of Oklahoma Press 1951), and Don G. Wyckoff’s Oklahoma Archeology: A 1981 Perspective (Uni- versity of Oklahoma, Archeological Survey 1981). • Additional information was provided by Jenk Jones Jr., Tulsa • David Hampton, Tulsa • Office of Archives and Records, Oklahoma Department of Librar- ies • Oklahoma Historical Society. Guide to Oklahoma Museums by David C. Hunt (University of Oklahoma Press, 1981) was used as a reference. 751 A Brief History of Oklahoma The Prehistoric Age Substantial evidence exists to demonstrate the first people were in Oklahoma approximately 11,000 years ago and more than 550 generations of Native Americans have lived here. More than 10,000 prehistoric sites are recorded for the state, and they are estimated to represent about 10 percent of the actual number, according to archaeologist Don G. Wyckoff. Some of these sites pertain to the lives of Oklahoma’s original settlers—the Wichita and Caddo, and perhaps such relative latecomers as the Kiowa Apache, Osage, Kiowa, and Comanche. All of these sites comprise an invaluable resource for learning about Oklahoma’s remarkable and diverse The Clovis people lived Native American heritage. in Oklahoma at the Given the distribution and ages of studies sites, Okla- homa was widely inhabited during prehistory.