An Aquatic Safe Harbor Program for the Upper Etowah River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

REGIONAL RESOURCE PLAN Contents Executive Summary

REGIONAL RESOURCE PLAN Contents Executive Summary ................................................................5 Summary of Resources ...........................................................6 Regionally Important Resources Map ................................12 Introduction ...........................................................................13 Areas of Conservation and Recreational Value .................21 Areas of Historic and Cultural Value ..................................48 Areas of Scenic and Agricultural Value ..............................79 Appendix Cover Photo: Sope Creek Ruins - Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area/ Credit: ARC Tables Table 1: Regionally Important Resources Value Matrix ..19 Table 2: Regionally Important Resources Vulnerability Matrix ......................................................................................20 Table 3: Guidance for Appropriate Development Practices for Areas of Conservation and Recreational Value ...........46 Table 4: General Policies and Protection Measures for Areas of Conservation and Recreational Value ................47 Table 5: National Register of Historic Places Districts Listed by County ....................................................................54 Table 6: National Register of Historic Places Individually Listed by County ....................................................................57 Table 7: Guidance for Appropriate Development Practices for Areas of Historic and Cultural Value ............................77 Table 8: General Policies -

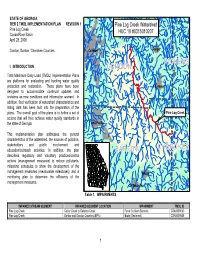

Responsibility for Management Measures

STATE OF GEORGIA TIER 2 TMDL IMPLEMENTATION PLAN REVISION 1 Pine Log Creek Watershed Pine Log Creek HUC 10 #0315010207 Coosa River Basin April 28, 2006 Gordon, Bartow, Cherokee Counties Calhoun Ranger PICKENS I. INTRODUCTION GORDON Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) Implementation Plans are platforms for evaluating and tracking water quality protection and restoration. These plans have been Fairmount designed to accommodate continual updates and revisions as new conditions and information warrant. In addition, field verification of watershed characteristics and listing data has been built into the preparation of the plans. The overall goal of the plans is to define a set of Pine Log Creek actions that will help achieve water quality standards in the state of Georgia. Adairsville This implementation plan addresses the general characterist ics of the watershed, the sources of pollution, stakeholder s and public involvement, and CHEROKEE education/o utreach activities. In addition, the plan BARTOW describes regulatory and voluntary practices/control actions (management measures) to reduce pollutants, milestone schedules to show the development of the management measures (measurable milestones), and a White monitoring plan to determine the efficiency of the management measures. Cartersville Table 1. IMPAIRMENTS IMPAIRED STREAM SEGMENT IMPAIRED SEGMENT LOCATION IMPAIRMENT TMDL ID Pine Log Creek Cedar Creek to Salacoa Creek Fecal Coliform Bacteria CSA0000060 Pine Log Creek Bartow and Gordon Counties (EPA) Biota (Sediment) CSA0000059 1 Plan for Pine Log Creek HUC 10 # 0315010207 II. GENERAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE WATERSHED Write a narrative describing the watershed, HUC 10 #0315010207. Include an updated overview of watershed characteristics. Identify new conditions and verify or correct information in the TMDL document using the most current data. -

1880 Census: Volumes 5 and 6

REPORT ON '.l'IIE COTTON PRODUCTION OF THE ST_ATE OF GEORGIA, WI'l'H A DESCRIPTION OF THE GENER.AL AGRICULTURAL Ji'EATUR.ES OF THE STATE. DY R. H. LOUGHRIDGE, F:a:. D.;, LA'l'E ASSlSTA:XT IX THE GEOHGIA GEOLOGIC.AL SURVEY, SI"ECIAL A.GENT. [NORTIIWEST GOORGL\ BY A. R. McCUTCHJrn, SPIWIAL AGENT.] i 259 TABLE OF CONTENT'S. !'age. LETTERS OF TRANSMITTAL .. -·_·-- .... ----·-- --- ---- ..• .• _. --·· .••.•.•..•. --- .•••••••..••••..•• _•. _--·- --- _•••• _•••••.••.••••• ~ii, viii TABULATED RESULTS OF THE ENUMEUATION •.... ·---. __ ---- ------ ---· ---· , .••..••••••••.•.•••••.•••••.•••••••••• -·- --·- -· __ . 1-8 TABLE !.-Area, Population, Tilled Land, and CottonProduction .... --·- ·--· ·-·- _••. _--· __ ••.• ···-. ··-•••••••..• --· .••... 3-5 TABLE IL-Acreage and Production of Leading Crops_·-_ •...••••. ~--··- .•.. -· __ ..••••.••• _. ____ ·-·-·. __ ·----· ___ -·. ____ _ fi-8 PART I. PHYSICO-GEOGRAPHICAL AND AGRICULTURAL FEATURES OF THE STATE OF GEORGIA .• ___ . __ •••...•••••• _ ••••••. __ •..•• _•• , __ 9-03 General Description of the State . _. _______ .. _•. _•.• __ •..•• _.... _. _... __ . ____ . ___ •.•• _.. _. _________ ..••••.• ______ . _.. _.. _. 11-53 Topography __ .... _............•.... ___ .. ·--· ______ --·-·· ..•• --· •.••... _________ . -· •••. ··-· ____ ·-·. _. ··-. _·- ___ ··---· 11 . Climate ____ ---···-·-··--·--·--· ................ ···---·-·-----··--·---··-··· ____ ·--··-··-·-····-----------·----····-- 11 Geological Features .• ___ .--·-.·----. ____ ... --·- ___ --··-··--.----- .. ---· .••••.•• _••..•• ·-··---·-_ .••• -

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers: Maps -- by Region Or

G3862 SOUTHERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3862 FEATURES, ETC. .C55 Clayton Aquifer .C6 Coasts .E8 Eutaw Aquifer .G8 Gulf Intracoastal Waterway .L6 Louisville and Nashville Railroad 525 G3867 SOUTHEASTERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3867 FEATURES, ETC. .C5 Chattahoochee River .C8 Cumberland Gap National Historical Park .C85 Cumberland Mountains .F55 Floridan Aquifer .G8 Gulf Islands National Seashore .H5 Hiwassee River .J4 Jefferson National Forest .L5 Little Tennessee River .O8 Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail 526 G3872 SOUTHEAST ATLANTIC STATES. REGIONS, G3872 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .B6 Blue Ridge Mountains .C5 Chattooga River .C52 Chattooga River [wild & scenic river] .C6 Coasts .E4 Ellicott Rock Wilderness Area .N4 New River .S3 Sandhills 527 G3882 VIRGINIA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G3882 .A3 Accotink, Lake .A43 Alexanders Island .A44 Alexandria Canal .A46 Amelia Wildlife Management Area .A5 Anna, Lake .A62 Appomattox River .A64 Arlington Boulevard .A66 Arlington Estate .A68 Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial .A7 Arlington National Cemetery .A8 Ash-Lawn Highland .A85 Assawoman Island .A89 Asylum Creek .B3 Back Bay [VA & NC] .B33 Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge .B35 Baker Island .B37 Barbours Creek Wilderness .B38 Barboursville Basin [geologic basin] .B39 Barcroft, Lake .B395 Battery Cove .B4 Beach Creek .B43 Bear Creek Lake State Park .B44 Beech Forest .B454 Belle Isle [Lancaster County] .B455 Belle Isle [Richmond] .B458 Berkeley Island .B46 Berkeley Plantation .B53 Big Bethel Reservoir .B542 Big Island [Amherst County] .B543 Big Island [Bedford County] .B544 Big Island [Fluvanna County] .B545 Big Island [Gloucester County] .B547 Big Island [New Kent County] .B548 Big Island [Virginia Beach] .B55 Blackwater River .B56 Bluestone River [VA & WV] .B57 Bolling Island .B6 Booker T. -

History of Bartow County, GA

www.gagenweb.org Electronic Edition (C) 2005 Chesley B. m. Ida Stephens (dec.) by whom there is one daughterAll rights Reserved. in the county, Lorena Barton. Malvina m. W. T. Bradford, who died in 1932, by whom there were Dela May, Clyde and Mattie (Harris). Lucius m. Sallie Mahan, daughted of David, and their daughter, Orie n. B. B, Branson of Kingston. Lula lives in' Pine Log. Lorena m. Lo G. Darnel1 (dec.), lives in Cartersville, His second wife was Mrs. Jane E. Bell, formerly Jane Uwe, by whom there were Stella, m. J. P. Adair, and Eddie, who died in Tex. His 3rd wife was Margaret McEver. (3) S. Margaret, b. 1829 in DeKalb county, m, in 1846 William Jackson Hicks, of English .descent, a son' of Jefferson Wyatt Hicks and Malinda Phelps, who came to this country in 1836, drew 1000 acres for service in War oP, 1812, fought in the Battle of New Orleans, died in 1841 and is buriet! in the Baker cemetery. W. J. Hicks was a bookkeeper for Etca-ah Iron Company several years, went to Calif. in 1850, in 1860 enlisted in Phillip's Legion, A son of Margaret and W. J. Hicks, James John W., b, 1848, m. in 1869 Sarah C. White, at Hartwell, Ga.; served in Co. "I", 1st Ga. Cav. C. M. S., died in 1898; Lucy H. Rucker, a daughter, lives at Elbertos. Eppe W. (dec.), a son, m, Mattie Wkd and have children in Cartersville. VIRGINIA COLONY: "Little Virginia" was settled on the Chero- kee and Cass county lines by families who came directly from Virginia about 1850. -

Civil War and Reconstruction Era Cass/Bartow County

CIVIL WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION ERA CASS/BARTOW COUNTY, GEORGIA Except where reference is made to the work of others, the work described in this dissertation is my own or was done in collaboration with my advisory committee. This dissertation does not include proprietary or classified information. _______________________________ Keith Scott Hébert Certificate of Approval: ____________________________ ____________________________ Anthony G. Carey Kenneth W. Noe, Chair Associate Professor Professor History History ____________________________ ____________________________ Kathryn H. Braund Keith S. Bohannon Professor Associate Professor History History University of West Georgia ____________________________ George T. Flowers Interim Dean Graduate School CIVIL WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION ERA CASS/BARTOW COUNTY, GEORGIA Keith Scott Hébert A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama May 10, 2007 CIVIL WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION ERA CASS/BARTOW COUNTY, GEORGIA Keith Scott Hébert Permission is granted to Auburn University to make copies of this dissertation at its discretion, upon request of individuals or institutions and at their expense. The author reserves all publication rights. ________________________________ Signature of Author ________________________________ Date of Graduation iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT CIVIL WAR AND RECONSTRUCTION ERA CASS/BARTOW COUNTY, GEORGIA Keith Scott Hébert Doctor of Philosophy, May, 10, 2007 (M.A., -

Aggeorgia Leader Spring 2020

Spring 2020 Back to Basics 101 Farm to Table ABAC Ag Fellows Program Property for Sale Leader is published quarterly for stockholders, directors and friends of AgGeorgia Farm Credit. PRESIDENT Jack C. Drew, Jr. BOARD OF DIRECTORS Jack W. Bentley, Jr. W. Howard Brown Billy J. Clary Guy A. Daughtrey Brian Grogan Ronney S. Ledford Robert G. (Bobby) Miller Richard David (Dave) Neff J. Dan Raines, Jr. George R. Reeves Joe A. (Al) Rowland Anne G. Smith David H. Smith Glee C. Smith Franklin B. Wright MANAGE YOUR EDITOR & SENIOR ACCOUNT ONLINE MARKETING SPECIALIST Rhonda Shannon PUBLISHING DIRECTOR Jenny Grounds When you want to withdraw funds, make a loan payment or view important tax documents, you need DESIGNERS Joey Ayer easy and secure access to your account. With our online Gwen Carroll solution – AccountAccess – you can manage your Phereby Derrick account when it’s convenient for you! Athina Eargle PRINTER Sun Solutions TO SIGN UP: Address changes, questions, comments or • Locate your account number on your loan documents or requests for copies of our financial reports a recent bill. should be directed to AgGeorgia Farm Credit by writing P.O. Box 1820, Perry, GA 31069 or • Visit aggeorgia.com or download the AgGeorgia mobile calling 800-768-FARM. Our quarterly financial report can also be obtained on our website: app on your smartphone. www.aggeorgia.com • Click “Sign up” under “AccountAccess.” Email: [email protected]. SIGN UP TODAY FOR EASY MONEY MANAGEMENT SO YOU CAN GET BACK TO WHAT’S MOST IMPORTANT! ON THE COVER: Gabrielle Ius, a student at Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College in Tifton, spent some time in Washington, DC, through the Ag Fellows program at ABAC. -

Assessment COVER Vol 2.Pub

FT RA D Cherokee County Community Assessment Vol. 2: Technical Data and Analyses January, 2007 An Element of the Joint Comprehensive Plan—2030 For Cherokee County and the Cities of Ball Ground, Waleska and Woodstock, Georgia Plan Cherokee Team: ROSS+associates | McBride Dale Clarion | Day Wilburn Associates | Robert Charles Lesser & Company Joint Comprehensive Plan Tenth-Year Update Cherokee County, Ball Ground, Waleska and Woodstock Community Assessment Vol. 2: Technical Data and Analyses Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1 Demographics ......................................................................................................... 2 Population and Employment Forecasts............................................................................... 2 Analysis of Population Forecasts........................................................................................ 2 Analysis of Household and Housing Forecasts .................................................................. 3 Analysis of Employment Forecasts .................................................................................... 4 Forecasts of Other Factors .................................................................................................. 4 Population......................................................................................................................... 10 Total County .................................................................................................................... -

Cartersville Brewery Surplus Land Cartersville, GA Offering Memorandum

CARTERSVILLE BREWERY SURPLUS LAND CARTERSVILLE, GA Offering Memorandum BREWERY SURPLUS LAND PRESENTED BY :: FRED RODDY CARTERSVILLE Senior Vice President Investment Properties 404.812.5147 Table of Contents BREWERY 1. Property Summary 1 SURPLUS LAND 2. Market Overview 6 CARTERSVILLE BREWERY SURPLUS LAND SURPLUS CARTERSVILLE BREWERY | P roperty Overview roperty Overview 02 Property Overview Property Summary Map Aerial PROPERTY SUMMARY CBRE is pleased to present the exclusive opportunity to acquire the Busch Cartersville Surplus Land site, located at 100 Busch Drive, Cartersville, GA. The surplus land site is contiguous to the current Busch Brewery and is located along Hwy 411 (between Harden Bridge Road and Cowan Drive), less than 40 miles from the I-75/I-85 junction. The surplus land around the brewery has the potential to be developed into an industrial park or residential community once market conditions return to normalcy and support a development of these uses. The property is approximately 1,050 acres and has multiple commercial and industrial zonings. BREWERY 100 Busch Drive, NE ADDRESS: SURPLUS Cartersville, GA 30184 LAND MUNICIPALITY: Bartow County / City of Cartersville PROPERTY SIZE: 1,050 acres ± Bartow County: B-P/I-2/C-1 City of Cartersville: General ZONING: Commercial (G-C), Heavy Industrial (H-I) and Business Park Overlay District UTILITIES AVAILABLE Water, sewer, electricity I-75 - 51,000+ AADT: U.S. HWY 411 - 10,300+ Parcel id’s Multiple 1 CARTERSVILLE BREWERY SURPLUS LAND LoCATION AERIAL/ZONING Zoned C-1 Zoned B-P Bartow -

Descriptions of Triangulation Stations in Georgia

' Otfc No. 73 DEPARTMENTDE OF COMMERCE " ^^ m in U. S. COAST AND GEODETIC SURVEY n I E. LESTER JONES, Superintendent GEODESY DESCRIPTIONS OF TRIANGULATION STATIONS IN GEORGIA BY CLARENCE H. SWICK Geodetic Computer, U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey Special Publication No 45 1 PRICE, 10 CENTS Sold only by the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C. WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1917 ^^^^^ a^^m^^^^K^^mmmaKmmi^t^^^^m^^^^^^^^^^m^^^^^^mm^m^mmom .,..._!L \ x- *essmsmm Serial No. 73 DEPARTMENT OF ' COMMERCE U. S. COAST AND GEODETIC SURVEY E. LESTER JONES, Superintendent GEODESY DESCRIPTIONS OF TRIANGULATION STATIONS IN GEORGIA BY CLARENCE H. SWICK Geodetic Computer, U. S. Coast and Geodetic Survey Special Publication No. 45 PRICE, 10 CENTS Sold only by the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C. WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1917 QB 31/ 1917 CONTENTS. Page. Introduction 5 Descriptions of stations 6 Marking of stations 6 Oblique arc, primary triangulation 8 Oblique arc to Augusta, secondary triangulation 11 Savannah River 14 Savannah River to Sapelo Sound 19 Sapelo Sound to St. Simon Sound 26 St. Simon Sound to St. Marys River 36 Index 41 3 DESCRIPTIONS OF TRIANGULATION STATIONS IN GEORGIA. By Clarence H. Swick, Geodetic Computer, U. S., Coast and Geodetic Survey. INTRODUCTION. This publication contains all the available descriptions of the triangulation stations the geographic positions of which are given in Special Publication No. 43. With the exception of a few supplemen- tary stations along the oblique arc, the descriptions and geographic positions of all triangulation stations in Georgia determined pre- vious to 1917 are included in this publication and in Special Publi- cation No. -

Bartow County

www.gagenweb.org Electronic (C) 2005 All Rights Reserved. Gen. Francis S.. Bartow-, for whom the county \%-aslast named (from an oil painting in the library of the Georgia Historical Society, Visit us - http://www.gagenweb.orgSavannah). Electronicwww.gagenweb.org (C) 2005 All Rights Reserved. THE HISTORY OF BART0 W COUNTY FORMERLY CASS LUCY JOSEPHINE CUNYUS Visit us - http://www.gagenweb.org Electronic (C) 2005www.gagenweb.org All Rights Reserved. COPYRIMT, 1983 =TOW COUNTY, GA. by Tribune Publishing Co., I: ing by 3. M. MArbut, Inc. ngsVisit by usJournal - http://www.gagenweb.org Engraving Cc www.gagenweb.org Electronic (C) 2005 All Rights Reserved. Visit us - http://www.gagenweb.org www.gagenweb.org Electronic (C) 2005 All Rights Reserved. 1. Gen:pe 11. Aul~r-y. ?. Lucy J. Cunyus. 3. Xrtllur I-. Seal. -1. Clnutir C. Pittman. Visit us - http://www.gagenweb.org www.gagenweb.org Electronic (C) 2005 All Rights Reserved. INTRODUCTION At its regular session in the year 1929 the General Assembly of the State of Georgia passed the following resolution : No. 36 "Resolved, by the General Assembly of Georgia, both Houses thereof concurring therein, that the judges of the superior courts of the State are hereby earnestly requested to give in charge to the grand jury of each county in their several circuits, at the next term of the court therein, the urgent request of this General Assem- bly that they will secure the consent of some competent person in their county to prepare between now and February 13,)1933, being Georgia Day, as nearly a corn- glete history of the formation, development, and progress of said county from its creation up to that date, to- gether with accounts of such persons, families, and public events as have given character and fame to the county, the State, and the Nation. -

Geological Survey

DEPAETMENT OP THE INTEBIOE BULLETIN OP THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY ]STo. 5 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PKINTING- .OFFICE 1884 UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY J. W. POWELL DIRECTOR A. DICTIONARY OF ALTITUDES THE UNITED STATES COMPILED BY HENRY GANNETT CHIEF GEOGRAPHER WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTPNG OFFICE 1884 LETTER OF TBANSMITAL. DEPARTMENT'OF THE INTERIOR, UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, Washington, D. 0., November 1,1883, SIR : I have the honor to transmit herewith the manuscript of a Dic tionary of Altitudes. The work of making a compilation of measure ments of altitude was commenced by me under the auspices of the Geological Survey of the Territories, by which organization three differ ent editions of the results were published, under the title of " Lists of Elevations," in the years 1873, 1875, and ,1877, respectively. These earlier editions related principally to that portion of the country west of the Mississippi River. The present work embraces within its scope the whole country. The elevations are tabulated by States and Terri tories, alphabetic arrangement being observed throughout. Yery respectfully, yours, HENRY GANNETT, Chief Geographer. Hon. J. W. POWELL, Director United States Geological Survey. (129) CONTENTS Page. Letter of transmittal...................................................... 5 Table of contents.......................................................... 7 Discussion of authorities......................... .$........................ 9 Abbreviations of names of railroads........................................ 17