Economic Perspective on the Building of the Canadian Pacific Railway Introduction Chronology of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 2007 News.Pub

WCRA NEWS MARCH 2007 AGM FEB. 27, 2007 WESTERN RAILS SHOW MARCH 18, 2007 WCRA News, Page 2 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING NOTICE Notice is given that the Annual General Meeting of the West Coast Railway Association will be held on Tuesday, February 27 at 1930 hours at Rainbow Creek Station. The February General Meeting of the WCRA will be held at Rainbow Creek Station in Confederation Park in Burnaby following the AGM. ON THE COVER Drake Street Roundhouse, Vancouver—taken November 1981 by Micah Gampe, and donated to the 374 Pavilion by Roundhouse Dental. Visible from left to right are British Columbia power car Prince George, Steam locomotive #1077 Herb Hawkins, Royal Hudson #2860’s tender, and CP Rail S-2 #7042 coming onto the turntable. In 1981, the roundhouse will soon be vacated by the railway, and the Provincial collection will move to BC Rail at North Vancouver. The Roundhouse will become a feature pavilion at Expo 86, and then be developed into today’s Roundhouse Community Centre and 374 Pavilion. Thanks to Len Brown for facilitating the donation of the picture to the Pavilion. MARCH CALENDAR • West Coast Railway Heritage Park Open daily 1000 through 1700k • Wednesday, March 7—deadline for items for the April 2007 WCRA News • Saturday, March 17 through Sunday, March 25—Spring Break Week celebrations at the Heritage Park, 1000—1700 daily • Tuesday, March 20—Tours Committee Meeting • Tuesday, March 27, 2007—WCRA General Meeting, Rainbow Creek Station in Confederation Park, Burnaby, 1930 hours. The West Coast Railway Association is an historical group dedicated to the preservation of British Columbia railway history. -

Transportation on the Minneapolis Riverfront

RAPIDS, REINS, RAILS: TRANSPORTATION ON THE MINNEAPOLIS RIVERFRONT Mississippi River near Stone Arch Bridge, July 1, 1925 Minnesota Historical Society Collections Prepared by Prepared for The Saint Anthony Falls Marjorie Pearson, Ph.D. Heritage Board Principal Investigator Minnesota Historical Society Penny A. Petersen 704 South Second Street Researcher Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 Hess, Roise and Company 100 North First Street Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 May 2009 612-338-1987 Table of Contents PROJECT BACKGROUND AND METHODOLOGY ................................................................................. 1 RAPID, REINS, RAILS: A SUMMARY OF RIVERFRONT TRANSPORTATION ......................................... 3 THE RAPIDS: WATER TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS .............................................. 8 THE REINS: ANIMAL-POWERED TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ............................ 25 THE RAILS: RAILROADS BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ..................................................................... 42 The Early Period of Railroads—1850 to 1880 ......................................................................... 42 The First Railroad: the Saint Paul and Pacific ...................................................................... 44 Minnesota Central, later the Chicago, Milwaukee and Saint Paul Railroad (CM and StP), also called The Milwaukee Road .......................................................................................... 55 Minneapolis and Saint Louis Railway ................................................................................. -

IN MEMORIAM 205 While We Were Attempting N Andakna the Other Member of the Party Visited the Ronti Pass, Camping a Few Hundred Feet Below the Summit, and Rejoined Us

IN MEMORIAM 205 While we were attempting N andakna the other member of the party visited the Ronti Pass, camping a few hundred feet below the summit, and rejoined us. at the base. Thanks to Umrao Singh our relays of atta and vegetables from Sutol reached us in the upper valley without a hitch. However, we had relied on bharal to supplement our tinned meat and never saw a sign of one. There were monal pheasant and jungle fowl in plenty in the Upper Nandagini and we should have been better off with a shotgun than a rifle. IN MEMORIAM ARTHUR OLIVER WHEELER I860-l945 THE Grand Old Man of Canadian mountaineering has at last in his 85th year bid goodbye to his beloved mountains to pass on to the summits that lie beyond. In the history of Alpine sport and scientific exploration in the Rockies Wheeler will always occupy the place that in an earlier generation men like C. E. Mathews and Tyndall occupied., both in the literal and in the spiritual sense, in the opening up of the Alps. In him long sustained personal achievement and the power . of inspiring others, scientific interest and the sheer joy of doing and beholding, were blended in a characteristic and irresistibly infectious enthusiasm. Born in 186o, of a younger branch of an old Irish county family, he came out with his parents to Canada in 1876 and took up the pro fession of land surveying in the Province of Ontario. His work took him steadily westwards, first to the~. still largely unexplored country north of the Great Lakes, then to the Manitoban prairie where, in I 88 5, he played his part, as an officer in the Intelligence. -

Transcontinental Railways and Canadian Nationalism Introduction Historiography

©2001 Chinook Multimedia Inc. Page 1 of 22 Transcontinental Railways and Canadian Nationalism A.A. den Otter ©2001 Chinook Multimedia Inc. All rights reserved. Unauthorized duplication or distribution is strictly prohibited. Introduction The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) has always been a symbol of Canada's nation-building experience. Poets, musicians, politicians, historians, and writers have lauded the railway as one of the country's greatest achievements. Indeed, the transcontinental railway was a remarkable accomplishment: its managers, engineers, and workers overcame incredible obstacles to throw the iron track across seemingly impenetrable bogs and forests, expansive prairies, and nearly impassable mountains. The cost in money, human energy, and lives was enormous. Completed in 1885, the CPR was one of the most important instruments by which fledgling Canada realized a vision implicit in the Confederation agreement of 1867-the building of a nation from sea to sea. In the fulfilment of this dream, the CPR, and subsequently the Canadian Northern and Grand Trunk systems, allowed the easy interchange of people, ideas, and goods across a vast continent; they permitted the settlement of the Western interior and the Pacific coast; and they facilitated the integration of Atlantic Canada with the nation's heartland. In sum, by expediting commercial, political, and cultural intercourse among Canada's diverse regions, the transcontinentals in general, and the CPR in particular, strengthened the nation. Historiography The first scholarly historical analysis of the Canadian Pacific Railway was Harold Innis's A History of the Canadian Pacific Railway. In his daunting account of contracts, passenger traffic, freight rates, and profits, he drew some sweeping conclusions. -

Review Article

Review Article Nailing Jelly to a Wall: Possibilities in Intellectual History by TERRY COOK A Disciplined Intelligence: Critical Inquiry and Canadian Thought in the Victorian Era. A.B. McKILLOP, Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1979. xii, 287p. ISBN 0-7735-0343-9 $21.95 ISBN 0-7735-0344-7 $9.95 pa. Promise of Eden: The Canadian Expansionist Movement and the Idea of the West, 1856-1900. DOUG OWRAM. Toronto, et. a].: University of Toronto Press, 1980. x, 264p. ISBN 0-8020-5483-8 $25.00 ISBN 0-8020-6385-3 $10.00 pa. Writing intellectual history, its principal Canadian pioneer once claimed, is like trying to nail jelly to a wall.' The subject is amorphous and difficult to pin down, its practi- tioners forced to sift through an ethereal realm of ideas, myths, attitudes, assumptions, values, feelings, and beliefs, rather than through concrete, quantifiable data of events and facts familiar to most other historians. While the outcome of a clash of two armies in the field, of two politicians on the hustings, of union and management in the streets, of two corporations in the stock market is relatively clear, the result of a conflict be- tween two thinkers, two ideas, or two general sets of values is immeasurably less so. Quite simply, the remains left by most historical figures - acts of state implemented, constituency organizations established, wages earned, profits posted, goods exported, factories started, railways built, territories explored - are more concrete and their causative historical impact far more measurable than is the legacy left by intellectuals. The concrete remains of the intellectual - books, articles, manuscripts, reports of speeches - are of little help. -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

Rocky Mountain Express

ROCKY MOUNTAIN EXPRESS TEACHER’S GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 A POSTCARD TO THE EDUCATOR 4 CHAPTER 1 ALL ABOARD! THE FILM 5 CHAPTER 2 THE NORTH AMERICAN DREAM REFLECTIONS ON THE RIBBON OF STEEL (CANADA AND U.S.A.) X CHAPTER 3 A RAILWAY JOURNEY EVOLUTION OF RAIL TRANSPORT X CHAPTER 4 THE LITTLE ENGINE THAT COULD THE MECHANICS OF THE RAILWAY AND TRAIN X CHAPTER 5 TALES, TRAGEDIES, AND TRIUMPHS THE RAILWAY AND ITS ENVIRONMENTAL CHALLENGES X CHAPTER 6 DO THE CHOO-CHOO A TRAIL OF INFLUENCE AND INSPIRATION X CHAPTER 7 ALONG THE RAILROAD TRACKS ACTIVITIES FOR THE TRAIN-MINDED 2 A POSTCARD TO THE EDUCATOR 1. Dear Educator, Welcome to our Teacher’s Guide, which has been prepared to help educators integrate the IMAX® motion picture ROCKY MOUNTAIN EXPRESS into school curriculums. We designed the guide in a manner that is accessible and flexible to any school educator. Feel free to work through the material in a linear fashion or in any order you find appropriate. Or concentrate on a particular chapter or activity based on your needs as a teacher. At the end of the guide, we have included activities that embrace a wide range of topics that can be developed and adapted to different class settings. The material, which is targeted at upper elementary grades, provides students the opportunity to explore, to think, to express, to interact, to appreciate, and to create. Happy discovery and bon voyage! Yours faithfully, Pietro L. Serapiglia Producer, Rocky Mountain Express 2. Moraine Lake and the Valley of the Ten Peaks, Banff National Park, Alberta 3 The Film The giant screen motion picture Rocky Mountain Express, shot with authentic 15/70 negative which guarantees astounding image fidelity, is produced and distributed by the Stephen Low Company for exhibition in IMAX® theaters and other giant screen theaters. -

Canadian Pacific Railway Investigation of Safety-Related Occurrences Protocol Considered Helpful by Both Labor and Management

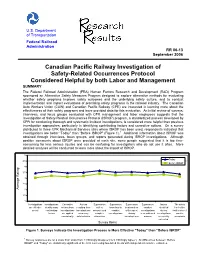

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Railroad Administration RR 06-13 September 2006 Canadian Pacific Railway Investigation of Safety-Related Occurrences Protocol Considered Helpful by both Labor and Management SUMMARY The Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) Human Factors Research and Development (R&D) Program sponsored an Alternative Safety Measures Program designed to explore alternative methods for evaluating whether safety programs improve safety outcomes and the underlying safety culture, and to conduct implementation and impact evaluations of promising safety programs in the railroad industry. The Canadian Auto Workers Union (CAW) and Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) are interested in learning more about the effectiveness of their safety programs and have provided data for this evaluation. An initial review of surveys, interviews, and focus groups conducted with CPR management and labor employees suggests that the Investigation of Safety-Related Occurrences Protocol (ISROP) program, a standardized process developed by CPR for conducting thorough and systematic incident investigations, is considered more helpful than previous investigation approaches, particularly in identifying contributing factors and corrective actions. On a survey distributed to three CPR Mechanical Services sites where ISROP has been used, respondents indicated that investigations are better “Today” than “Before ISROP” (Figure 1).1 Additional information about ISROP was obtained through interviews, focus groups, and reports generated during ISROP investigations. Although positive comments about ISROP were provided at each site, some people suggested that it is too time- consuming for less serious injuries and can be confusing for investigators who do not use it often. More detailed analyses will be conducted to learn more about the impact of ISROP. -

Canadian Pacific NOV 18 2015 NS PR.Pdf

CP discloses full details of offer letter to Norfolk Southern CALGARY, Nov. 18, 2015 /PRNewswire/ - Canadian Pacific (TSX:CP) (NYSE: CP) today disclosed the contents of the offer letter it sent to Norfolk Southern Corp. (NS) on November 17, 2015 to clarify the details of a proposal that would result in the creation of a pro- competitive, pro-customer, coast-to-coast transportation solution. CP also wishes to correct any misconceptions about the sizable premium offered to NS shareholders. The verbatim text of the letter addressed to NS CEO James Squires is dated November 9, 2015 and since that time, there has been considerable appreciation to the NS stock price due to market speculation regarding a potential combination with CP. Mr. Squires asked CP CEO Hunter Harrison to hold off on sending this letter until such time as the two CEO's could meet face to face, which occurred last Friday November 13, 2015. Dear Jim, We believe that combining our two great organizations will allow us to form an integrated transcontinental railroad with the scale and reach to deliver unsurpassed levels of safety and service to our customers and communities while also increasing competition and creating significant shareholder value. We propose a 50% cash 50% stock transaction based on Friday's closing stock price for both CP and NSC in which NSC shareholders would receive $46.72 in cash and 0.348 shares of stock in a new company which would own CP and NSC. The new company would be listed on both the New York and Toronto Stock Exchanges, and maintain a strong investment grade credit rating. -

The Honorable Connie Bernardy, DFL Lead House Transportation

395 John Ireland Boulevard Saint Paul, Minnesota 55155 July 25, 2017 The Honorable Paul Torkelson, Chair The Honorable Scott Newman, Chair House Transportation Finance Committee Senate Transportation Finance & Policy Committee 381 State Office Building 3105 Minnesota Senate Building Saint Paul, MN 55155 Saint Paul, MN 55155 The Honorable Linda Runbeck, Chair The Honorable Scott Dibble House Transportation & Regional Governance Policy Ranking Minority Member Committee Senate Transportation Finance & Policy Committee 417 State Office Building 2213 Minnesota Senate Building Saint Paul, MN 55155 Saint Paul, MN 55155 The Honorable Frank Hornstein, DFL Lead The Honorable Connie Bernardy, DFL Lead House Transportation Policy & Finance Committee House Transportation & Regional Governance 243 State Office Building Policy Committee Saint Paul, MN 55155 253 State Office Building Saint Paul, MN 55155 RE: 2016 Annual Railroad Lighting Report Dear Legislators: The Minnesota Department of Transportation is pleased to provide the annual report on Railroad Yard Lighting. This report is required under Minnesota Statute 219.375, subdivision 4. The report describes the information provided by the Class I and Class II railroads and the United Transportation Union representatives about the condition, efficacy and maintenance of railroad yard lighting. As the statute requires, the differences and discrepancies between the information provided by the railroads and the UTU were analyzed. Included within the report are recommendations from MnDOT in order to improve compliance and reporting by the railroads and the UTU. Please contact me if you have questions about this report, or you may contact Bill Gardner in the Office of Freight & Commercial Vehicle Operations, Rail Division at [email protected] or at 651-366-3665. -

South Dakota's Railroads

South Dakota’s Railroads South Dakota State Historic Preservation Office South Dakota’s Railroads: An Historic Context Prepared for: South Dakota State Historic Preservation Office 900 Governors Drive Pierre, South Dakota 57501 Prepared by: Mark Hufstetler and Michael Bedeau Renewable Technologies, Inc. 511 Metals Bank Bldg. Butte, Montana 59701 July 1998 Revised, December 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.................................................................................................................................2 A. Purpose of this Document..............................................................................................2 B. Methodology ..................................................................................................................3 2. The Importance of Railroads to South Dakota ...........................................................................4 3. The History of Railroading in South Dakota..............................................................................5 A. Geographical Background .............................................................................................5 B. Establishment and Expansion: South Dakota Railroads in the Nineteenth Century......6 1. Beginnings (1851-1868) .....................................................................................6 2. The Little Dakota Boom and the First Railroads (1868-1873)...........................8 3. Railway Expansion During the Great Dakota Boom (1878-1887).....................9 4. The Impact and -

Canadian Pacific at the Glenbow: a Hundred Years of the CPR in Western Canada

Canadian Pacific at the Glenbow: A Hundred Years of the CPR in Western Canada by GLENN T. WRIGHT All aboard! Two hundred and fifty historians, archivists, curators, and rail fans heard the traditional call of the railway porter and gathered at the Glenbow Museum last September to commemorate one hundred years of the Canadian Pacific Railway in Western Canada. Sponsored by the Glenbow-Alberta Institute with assistance from the National Museums Corporation and Canadian Pacific Limited. the festivities consisted of three major elements. In August the celebration began with the opening of the "Great CPR Exposition," a large exhibition that takes a comprehensive look at the construction, arrival and impact of the CPR on the Canadian West. During the month of September, the CPR West Conference attracted a good number of professionals and non-professionals and demonstrated that research on various aspects of CPR history is alive and well. To complement both the exhibition and the conference, Glenbow also sponsored the publication of a souvenir book, Trailoflron: The CPR andthe Birth qfthr West by William McKee and Georgeen Klassen. The centrepiece of Glenbow's tribute to the CPR is the6'Great CPR Exposition," the largest and most ambitious exhibition ever mounted by the Museum. Glenbow staff spent over two years collecting materials and conducting original research, and the result is impressive. The exhibition is an attempt to portray the history of the Canadian Pacific Railway and its impact on the social and economic development of Western Canada from the time of its inception and construction to the 1930s. Historical records have been drawn from virtually every media that one would find in an archives or museum.