Isaiah 44:5: Textual Criticism and Other Arguments E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“As Those Who Are Taught” Symposium Series

“AS THOSE WHO ARE TAUGHT” Symposium Series Christopher R. Matthews, Editor Number 27 “AS THOSE WHO ARE TAUGHT” The Interpretation of Isaiah from the LXX to the SBL “AS THOSE WHO ARE TAUGHT” The Interpretation of Isaiah from the LXX to the SBL Edited by Claire Mathews McGinnis and Patricia K. Tull Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta “AS THOSE WHO ARE TAUGHT” Copyright © 2006 by the Society of Biblical Literature All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office, Society of Biblical Literature, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data “As those who are taught” : the interpretation of Isaiah from the LXX to the SBL / edited by Claire Mathews McGinnis and Patricia K. Tull. p. cm. — (Society of biblical literature symposium series ; no. 27) Includes indexes. ISBN-13: 978-1-58983-103-2 (paper binding : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-58983-103-9 (paper binding : alk. paper) 1. Bible. O.T. Isaiah—Criticism, interpretation, etc.—History. 2. Bible. O.T. Isaiah— Versions. 3. Bible. N.T.—Criticism, interpretation, etc. I. McGinnis, Claire Mathews. II. Tull, Patricia K. III. Series: Symposium series (Society of Biblical Literature) ; no. 27. BS1515.52.A82 2006 224'.10609—dc22 2005037099 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, recycled paper conforming to ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) and ISO 9706:1994 standards for paper permanence. -

Isaiah 44:6-23

Isaiah 44:6-23 Gods made of wood 1. Introduction The book of Isaiah emphasizes God’s greatness. His greatness manifests itself in creation and in how he governs history. But God’s greatness is equally apparent in the comparison between him and the idols. Isaiah 44 openly mocks those who fashion and worship idols. The idols and those who made them are as it were called to defend themselves in court. God challenges them to show their greatness, but the silence is deafening. It looks like idol worship no longer exists, but appearances are deceptive. Even today this chapter of Isaiah poses some very relevant questions. What has Western society accomplished with the gods of their own making? What does the future hold for you if you do not seek your salvation in the living God? 2. General Remarks 1. Idols cannot help With great irony, almost sarcastically, God shows us how ridiculous the idols are and how ridiculous it is to trust in them. This mocking of the idols has to be seen in light of the circumstances God’s people were in. God allows Isaiah to speak about the future of the people of Israel. We do not know exactly at what point in time the people heard these words. It is possible that they were already spoken before the deportation. It is also possible that the people did not hear or read these words until they actually were in exile. For our understanding of these words it does not make much difference. The people of Judah are in grave danger as far as their existence as a nation is concerned. -

The Eschatological Blessing (Hk'r"B.) of the Spirit in Isaiah: with Special Reference to Isaiah 44:1-5

DOI: https://doi.org/10.28977/jbtr.2016.10.39.307 The Eschatological Blessing (hk'r"B.) of the Spirit in Isaiah / YunGab Choi 307 The Eschatological Blessing (hk'r"B.) of the Spirit in Isaiah: with Special Reference to Isaiah 44:1-5 YunGab Choi* 1. Introduction The primary purpose of this paper is to explicate the identity of the “eschatological1) blessing (hk'r"B.) of the Spirit”2) in Isaiah 44:3. The Hebrew term — hk'r"B. — and its derivative form appear ten times (19:24, 25; 36:16; 44:3; *Ph. D in Old Testament at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. Assistant Professor of Old Testament at Kosin University. [email protected]. 1) The English term “eschatology” comes from Greek word eschatos (“last”). Accordingly in a broad sense, “[e]schatology is generally held to be the doctrine of ‘the last things’, or of ‘the end of all things.’” (Jürgen Moltmann, The Coming of God: Christian Eschatology [Minneapolis: Fortress Press,1996], 1). In a similar vein, Willem A. VanGemeren defines eschatology as “biblical teaching which gives humans a perspective on their age and a framework for living in hope of a new age” (Willem A. VanGemeren, Interpreting the Prophetic Word: An Introduction to the Prophetic Literature of the Old Testament [Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1990], 88). G. B. Caird defines eschatology as “the study of, or the corpus of beliefs held about, the destiny of man and of the world” (G. B. Caird, The Language and Imagery of the Bible [Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1980], 243). -

The Septuagint As Christian Scripture: Its Prehistory and the Problem of Its

OLD TESTAMENT STUDIES Edited by David J. Reimer OLD TESTAMENT STUDIES The mid-twentieth century was a period of great confidence in the study of the Hebrew Bible: many historical and literary questions appeared to be settled, and a constructive theological programme was well underway. Now, at the turn of the century, the picture is very different. Conflicting positions are taken on historical issues; scholars disagree not only on how to pose the questions, but also on what to admit as evidence. Sharply divergent methods are used in ever more popular literary studies of the Bible. Theological ferment persists, but is the Bible's theological vision coherent, or otherwise? The Old Testament Studies series provides an outlet for thoughtful debate in the fundamental areas of biblical history, theology and literature. Martin Hengel is well known for his seminal work on early Judaism and nascent Christianity. In this volume he turns his attention to the Septuagint—the first bible of the church, yet a product of Greek- speaking Judaism. Hengel probes into the historical and theological puzzles posed by the Septuagint opening a window on the formation of canon and attitudes to scripture in the Christian tradition, and on the relationship between Judaism and Christianity in the early centuries of the era. THE SEPTUAGINT AS CHRISTIAN SCRIPTURE THE SEPTUAGINT AS CHRISTIAN SCRIPTURE Its Prehistory and the Problem of Its Canon Martin Hengel with the assistance of Roland Deines Introduction by Robert Hanhart Translated by Mark E. Biddle T&T CLARK EDINBURGH & NEW YORK T&T CLARK LTD A Continuum imprint 59 George Street 370 Lexington Avenue Edinburgh EH2 2LQ New York 10017-6503 Scotland USA www.tandtclark.co.uk www.continuumbooks.com Copyright © T&T Clark Ltd, 2002 All rights reserved. -

Isaiah 40-66 God Comforts His People

Isaiah 40-66 God Comforts His People 41 Small Group Bible Studies By John Edmiston These studies are designed for personal or small group use and take about 45 minutes to an hour each. The questions are designed to be thought-provoking. There are eight or nine questions per lesson. The studies are interdenominational in nature. You will need: A good accurate translation of the Bible suitable for research purposes (not a paraphrase) A study Bible would be helpful The group leader should have access to a Bible dictionary or a commentary. Themes: Jesus in prophecy, the folly of idols, ethics, the sovereignty of God, the uniqueness of God, prophecy, justice, the love, mercy and compassion of God, God and Israel. © Copyright John Edmiston, 2019 Isaiah 40-66 by John Edmiston is Creative Commons, attribution required, non-commercial, share-alike - and may be freely used, translated, photocopied, printed, and distributed electronically for non-profit ministry purposes, however it may not be sold in any way. Isaiah 40:1-11 Some Big Themes Get Introduced Isaiah starts this section by throwing out 4 short snippets of the really BIG ideas that he will then develop through to the end of chapter 66. These are words of comfort for Jews in Babylon and are written for well into the future from Isaiah’s day two centuries earlier. Many of the prophecies have multiple references – Jews in Babylon, the time of Christ, the Gospel and Church, and the Return of the Lord. 1. Read Isaiah 40:1,2 – What is God saying to the Jews? Does God stay angry forever? What does this say about our relationship with God? 2. -

Isaiah 44-45A

Isaiah 44-45A • We ended last week as God revealed that Israel would be restored on the basis of grace o Because the nation could not receive God’s mercy on the basis of merit . Their fathers had sinned and their spokesmen had transgressed o So though grace was coming in a future day, judgment would come first . At the hands of the Babylonians o The final verse of chapter 43 alluded to that coming judgment Is. 43:28 “So I will pollute the princes of the sanctuary, And I will consign Jacob to the ban and Israel to revilement. o The meaning of v.28 is two-fold . The princes of the sanctuary are the priests who serve in the temple • They are polluted as the Babylonians destroyed the temple in 586 BC . And Jacob is consigned to the ban and revilement • They are reviled in the sense that they become captives of Babylon and are placed into slavery o God continues to link mercy and redemption with judgment . Though he brings judgment upon Israel for its sins, God doesn’t destroy the nation and will redeem it one day Is. 44:1 ¶ “But now listen, O Jacob, My servant, And Israel, whom I have chosen: Is. 44:2 Thus says the LORD who made you And formed you from the womb, who will help you, ‘ Do not fear, O Jacob My servant; And you Jeshurun whom I have chosen. Is. 44:3 ‘For I will pour out water on the thirsty land And streams on the dry ground; I will pour out My Spirit on your offspring And My blessing on your descendants; © 2010 – Verse By Verse Ministry of San Antonio (www.versebyverseministry.org) May be copied and distributed provided the document is reproduced in its entirety, including this copyright statement, and no fee is collected for its distribution. -

Biblical Proof of the Trinity Peace Church

1 Biblical Proof for the Trinity Today we are told that all religions lead to God, that Christianity is just one of many choices. However, in the gospels, Jesus does not allow for this plurality. Unlike every other religion, Christianity recognizes the divinity of Jesus Christ. The doctrine of the Trinity is one vital IN SUMMARY doctrine distinguishing true religion from false. Some religions want us to believe that they, too, are Christian religions. Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses like to emphasize our similarities. But their rejection of the divinity of Jesus separates So, there is only them from the true Christian Church. one God (Jehovah) (Deut 6:4) The Bible is clear – Jesus is God. Below is a list of passages from the Bible that make that evident. Begin at the top, work your way down, and recognize Jesus as Lord, as fully God. God (Jehovah) is Savior By the way, while Jehovah’s Witnesses use a different version of the Bible, which removes many (Isaiah 43:11) references to the Trinity, this list can be used in their Bible. When someone comes knocking on your door, wanting to talk about Jesus, you can use this list. Using their Bible, move through the God (Jehovah) is list, asking them if they agree with each summary of each verse, and by the end, they must admit the first and the last that Jesus truly is Jehovah. (Isaiah 44:6) Deuteronomy 6:4 - Hear, O Israel: The LORD our God, the LORD is one. God (Jehovah) is Summary - There is only one God the Alpha and the Omega. -

The Nature of God and Christ Doctrinal Study Paper

United Church of God, an International Association .......... The Nature of God and Christ Doctrinal Study Paper Approved by the Council of Elders August 2005 All scriptures are quoted from The Holy Bible, New King James Version (© 1988 Thomas Nelson, Inc., Nashville, Tennessee) unless otherwise noted. THE NATURE OF GOD AND CHRIST Doctrinal Study Paper Table of Contents Page Classical Trinitarian View of the Godhead 4 Question of Origins 5 Summary of Principal Views on the Origin of Christ 6 OLD TESTAMENT SECTION 6 The Tetragrammaton 6 The Shema and the “Oneness” of God 8 God (Elohim) in the Plural or Collective Sense 11 Anthropomorphic or Amorphical God 11 The God of the Old Testament 12 Theophanies 14 Angel of God’s Presence and YHWH 15 Who Was Married to Israel? 17 Who Led Israel to the Promised Land?—The 1 Corinthians 10:4 Question 19 NEW TESTAMENT SECTION 20 Neoplatonic, Gnostic and Jewish Concepts of the Logos 20 The Biblical Origin of the Logos 23 The Logos as the Agent of Creation 24 The Only Begotten Son of God 25 The Logos Empties Himself of Glory 26 The Logos Is Identified as Jesus Christ in Revelation 27 Christ’s Testimony of Glory He Shared With the Father 27 The Testimony of David Is Verified by Christ 28 Preexistence of Christ Confirmed by the Priesthood of Melchizedek 29 Christ’s Testimony of His Preexistence 31 Jesus Was Worshipped (Yet Only God Is to Be Worshipped) 32 The Testimony of Peter 32 God’s Purpose for Creating Humankind 33 Christ the Redeemer 34 God’s Purpose for Humanity 35 “One” (Greek Heis/Hen) God in the -

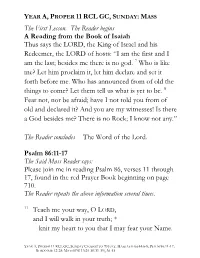

YEAR A, PROPER 11 RCL GC, S the First Lesson. the Reader Begins a Reading from the Book of Isaiah Thus Says the LORD, the King

YEAR A, PROPER 11 RCL GC, SUNDAY: MASS The First Lesson. The Reader begins A Reading from the Book of Isaiah Thus says the LORD, the King of Israel and his Redeemer, the LORD of hosts: “I am the first and I am the last; besides me there is no god. 7 Who is like me? Let him proclaim it, let him declare and set it forth before me. Who has announced from of old the things to come? Let them tell us what is yet to be. 8 Fear not, nor be afraid; have I not told you from of old and declared it? And you are my witnesses! Is there a God besides me? There is no Rock; I know not any.” The Reader concludes The Word of the Lord. Psalm 86:11-17 The Said Mass Reader says: Please join me in reading Psalm 86, verses 11 through 17, found in the red Prayer Book beginning on page 710. The Reader repeats the above information several times. 11 Teach me your way, O LORD, and I will walk in your truth; * knit my heart to you that I may fear your Name. YEAR A, PROPER 11 RCL GC, SUNDAY CLOSEST TO 20 JULY, MASS: ISAIAH 44:6-8; PSALM 86:11-17; ROMANS 8: 12-25; MATTHEW 13:24-30(31-35), 36-43 YEAR A, PROPER 11 RCL GC, SUNDAY: MASS 12 I will thank you, O LORD my God, with all my heart, * and glorify your Name for evermore. 13 For great is your love toward me; * you have delivered me from the nethermost Pit. -

The Mission's Beginning

Focal TEXTS Genesis 1:1; Isaiah 46:5–9; Acts 17:24–31 BackgrouND Genesis 1:1; Isaiah 44:6–28; 46:1–13; Acts 17:22–31 MAIN IDEA God’s mission begins from the foundation that God’s dominion is unlimited. QUESTION to EXPlore How big is your God? TEACHING AIM Lesson One To lead the class to suggest implications and actions that should follow from The Mission’s the biblical truth of God’s Beginning unlimited dominion UNIT ONE Foundational Truths About God’s Mission 11 12 Unit 1: Foundational Truths About God’s Mission BIble CommeNTS Understanding the Context The passages examined in this lesson focus on the teaching that there is one and only one God. This concept may seem elementary. However, people who lived two to three thousand years ago believed in many gods. For them, no single god could encompass dominion over everything. Israel’s eventual understanding of monotheism developed over several centuries. Israel came to view yhwh1 as an active agent in the affairs of daily life. The other gods were passive and immobile, unable to effect any change. The prophet of the exile (Isaiah 44:6–28; 46:1–13) argued that the imperial gods of Babylon offered no future. Only the Lord held dominion over the affairs of humanity. The acknowledgement that yhwh is the only deity provides the foundation for the mission of Israel and the church. Isaiah 44 proclaims that yhwh is King, Redeemer, and Warrior. “I am the first and I am the last; besides me there is no god” (Isa. -

Can I Really Trust the Bible? – a Compilation (Appropriate for High Schoolers and Older) Michael R

Can I Really Trust The Bible? – A Compilation (appropriate for High Schoolers and older) Michael R. Daily, February 2018 Other youth bible studies by Michael Daily available at: http://gciweb.org/2011/04/youth-bible-study-materials-michael-r-daily/ Reference #1: John Ankerberg & Dillon Burroughs, How Do We Know The Bible Is True?, AMG Publishers, 2008 Reference #2: Ken Ham & Bodie Hodge, How Do We Know The Bible Is True?, Vol. 1, Master Books, 2011 Reference #3: Clinton E. Arnold, How We Got The Bible: A Visual Journey, Zondervan, 2008 Reference #5: Josh McDowell & Dave Sterrett, Is The Bible True…Really?, Moody Publishers, 2011 Reference #6, Paul D. Wegner, The Journey from Texts to Translations, Baker Academic, 1999 Reference #7, John MacArthur, Why You Can Trust The Bible, audio DVD, Grace To You Ministries, 2006 Reference #8, Chuck Missler, Technology & The Bible, video DVD, Koinonia House Ministries, 2008 This study contains a series of lessons all related to trusting the Bible. Due to the large volume of evidence in multiple areas it will take 8 to 14 sessions to cover all of the material. However, the material has been broken up into lessons that can stand alone so that the leader can do some or all of the lessons as they see fit and as their teaching situation allows. Material from the appendices may also be used for additional lessons if so desired. Main Lesson Topics: 1) Introduction & Overview: Can I Really Trust The Bible? page 2 2) How Were The Books Of The Bible Selected? page 6 3) Does the Bible Give Evidence Of The Power -

The Book of Jeremiah: Realisation of Threats of the Torah – and Also of Promises?

Verbum et Ecclesia ISSN: (Online) 2074-7705, (Print) 1609-9982 Page 1 of 9 Original Research The Book of Jeremiah: Realisation of threats of the Torah – and also of promises? Author: The relationship between the Torah and the Prophets has been a matter of dispute. This article 1,2 Georg Fischer SJ discusses the links of the Book of Jeremiah especially with the warnings in Leviticus 26 and the Affiliations: curses in Deuteronomy 28, but then goes on to show that it also picks up promises from the 1Theological Faculty, Torah and thus indicates a way to salvation. In doing so, it comes close to the Book of Isaiah. Leopold-Franzens-Universität The intertextual comparison between these two prophetic books reveals that the entire Book of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria Isaiah may be the source for similar announcements in the Book of Jeremiah, yet also for taking a more nuanced stance. 2Department of Old Testament and Hebrew Intra-disciplinary and/or interdisciplinary implications: The literary relationship between Scriptures, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa the Torah and Prophets as well as between the Books of Isaiah and Jeremiah is seen anew from an Old Testament perspective with its dogmatic implication for a portrayal of God. Corresponding author: Georg Fischer SJ, Keywords: Relationship Torah – Jeremiah; Leviticus 26; Deuteronomy 28; Fulfilment of Torah [email protected] Promises; Relationship Book of Isaiah – Book of Jeremiah. Dates: Received: 06 Mar. 2019 Accepted: 04 July 2019 Introduction Published: 12 Dec. 2019 The Pro Pent congress 2014 on ‘Torah and Prophets: Isaiah and Jeremiah’ invited participants to How to cite this article: reflect ontwo fascinating relationships, namely, firstly, on the connection between two large parts of the Fischer SJ, G., 2019, ‘The Tanak, and secondly, on the link between two major prophetic books.