Britain and the Occupation of Germany, 1945-49 Daniel Luke

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'The Left's Views on Israel: from the Establishment of the Jewish State To

‘The Left’s Views on Israel: From the establishment of the Jewish state to the intifada’ Thesis submitted by June Edmunds for PhD examination at the London School of Economics and Political Science 1 UMI Number: U615796 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615796 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 7377 POLITI 58^S8i ABSTRACT The British left has confronted a dilemma in forming its attitude towards Israel in the postwar period. The establishment of the Jewish state seemed to force people on the left to choose between competing nationalisms - Israeli, Arab and later, Palestinian. Over time, a number of key developments sharpened the dilemma. My central focus is the evolution of thinking about Israel and the Middle East in the British Labour Party. I examine four critical periods: the creation of Israel in 1948; the Suez war in 1956; the Arab-Israeli war of 1967 and the 1980s, covering mainly the Israeli invasion of Lebanon but also the intifada. In each case, entrenched attitudes were called into question and longer-term shifts were triggered in the aftermath. -

British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964 William Styles Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge September 2016 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy William Styles British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964 This thesis is concerned with an analysis of British governmental attitudes and responses to communism in the United Kingdom during the early years of the Cold War, from the election of the Attlee government in July 1945 up until the election of the Wilson government in October 1964. Until recently the topic has been difficult to assess accurately, due to the scarcity of available original source material. However, as a result of multiple declassifications of both Cabinet Office and Security Service files over the past five years it is now possible to analyse the subject in greater depth and detail than had been previously feasible. The work is predominantly concerned with four key areas: firstly, why domestic communism continued to be viewed as a significant threat by successive governments – even despite both the ideology’s relatively limited popular support amongst the general public and Whitehall’s realisation that the Communist Party of Great Britain presented little by way of a direct challenge to British political stability. Secondly, how Whitehall’s understanding of the nature and severity of the threat posed by British communism developed between the late 1940s and early ‘60s, from a problem considered mainly of importance only to civil service security practices to one which directly impacted upon the conduct of educational policy and labour relations. -

Lord Healey CH MBE PC

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 31 (Incorporating the Proceedings of the Bomber Command Association’s 60th Anniversary Symposium) 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Photographs credited to MAP have been reproduced by kind permission of Military Aircraft Photographs. Copies of these, and of many others, may be obtained via http://www.mar.co.uk First published in the UK in 2004 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Typeset by Creative Associates 115 Magdalen Road Oxford OX4 1RS Printed by Advance Book Printing Unit 9 Northmoor Park Church Road Northmoor OX29 5UH 3 CONTENTS RECOLLECTIONS OF A SECRETARY OF STATE FOR 4 DEFENCE – The Rt Hon The Lord Healey CH MBE PC HOW DECISIVE WAS THE ROLE OF ALLIED AIR POWER 17 IN THE WAR IN THE PACIFIC, 1941-1945? by Sqn Ldr S I Richards SUMMARY OF THE MINUTES OF THE SEVENTEENTH 47 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING HELD IN THE ROYAL AIR FORCE CLUB ON 10 JUNE 2003 FEEDBACK 51 DEREK WOOD – AN OBITUARY 55 BOOK REVIEWS 56 PROCEEDINGS OF THE BOMBER COMMAND 82 ASSOCIATION 60TH ANNIVERSARY SYMPOSIUM HELD AT THE RAF MUSEUM, HENDON ON 12 OCTOBER 2002 UNDER THE CHAIRMANSHIP OF AIR MSHL SIR JOHN CURTISS KCB KBE 4 RECOLLECTIONS OF A SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE The Rt Hon The Lord Healey CH MBE PC I should perhaps start by saying that there is no specific theme to what I have to say. -

<K>EXTRACTS from the REPORT on the TRIPARTITE

Volume 8. Occupation and the Emergence of Two States, 1945-1961 Excerpts from the Report on the Potsdam Conference (Potsdam Agreement) (August 2, 1945) The Potsdam Conference between the leaders of the Soviet Union, the United States, and Great Britain was held at Cecilienhof Palace, the home of Crown Prince Wilhelm Hohenzollern, in Potsdam, Germany, from July 17 to August 2, 1945. The Soviet Union was represented by Josef Stalin; the U.S. was represented by President Harry S. Truman, who had only been in office for a few months, having succeeded Franklin Delano Roosevelt on April 12, 1945. Winston Churchill represented Great Britain at the start of the conference, but after the Labor Party won the elections of July 27, 1945, he was replaced by the new prime minister, Clement R. Attlee, who signed the agreement on behalf of Great Britain on August 2, 1945. The agreement reached by Stalin, Truman, and Attlee formed the basis of Allied occupation policy in the years to come. The provisions with the most far-reaching consequences included those concerning borders. It was agreed, for example, that the Oder- Neisse line would be established as Poland’s provisional western boundary, meaning that Poland would undergo a “western shift” at the expense of German territories in Pomerania, Silesia, and Eastern Prussia. It was also agreed that the territory around East Prussian Königsberg would be ceded to the Soviet Union. In addition, the conference settled upon the “transfer” of Germans from the new Polish territories and from Czechoslovakia and Hungary. These measures constituted an essential basis for the division of Germany and Europe. -

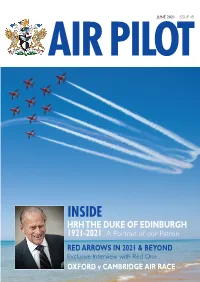

June 2021 Issue 45 Ai Rpi Lo T

JUNE 2021 ISSUE 45 AI RPI LO T INSIDE HRHTHE DUKE OF EDINBURGH 1921-2021 A Portrait of our Patron RED ARROWS IN 2021 & BEYOND Exclusive Interview with Red One OXFORD v CAMBRIDGE AIR RACE DIARY With the gradual relaxing of lockdown restrictions the Company is hopeful that the followingevents will be able to take place ‘in person’ as opposed to ‘virtually’. These are obviously subject to any subsequent change THE HONOURABLE COMPANY in regulations and members are advised to check OF AIR PILOTS before making travel plans. incorporating Air Navigators JUNE 2021 FORMER PATRON: 26 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Duxford His Royal Highness 30 th T&A Committee Air Pilot House (APH) The Prince Philip Duke of Edinburgh KG KT JULY 2021 7th ACEC APH GRAND MASTER: 11 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Henstridge His Royal Highness th The Prince Andrew 13 APBF APH th Duke of York KG GCVO 13 Summer Supper Girdlers’ Hall 15 th GP&F APH th MASTER: 15 Court Cutlers’ Hall Sqn Ldr Nick Goodwyn MA Dip Psych CFS RAF (ret) 21 st APT/AST APH 22 nd Livery Dinner Carpenters’ Hall CLERK: 25 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Weybourne Paul J Tacon BA FCIS AUGUST 2021 Incorporated by Royal Charter. 3rd Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Lee on the Solent A Livery Company of the City of London. 10 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Popham PUBLISHED BY: 15 th Air Pilot Flying Club The Honourable Company of Air Pilots, Summer BBQ White Waltham Air Pilots House, 52A Borough High Street, London SE1 1XN SEPTEMBER 2021 EMAIL : [email protected] 15 th APPL APH www.airpilots.org 15 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Oaksey Park th EDITOR: 16 GP&F APH Allan Winn EMAIL: [email protected] 16 th Court Cutlers’ Hall 21 st Luncheon Club RAF Club DEPUTY EDITOR: 21 st Tymms Lecture RAF Club Stephen Bridgewater EMAIL: [email protected] 30 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Compton Abbas SUB EDITOR: Charlotte Bailey Applications forVisits and Events EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTIONS: The copy deadline for the August 2021 edition of Air Pilot Please kindly note that we are ceasing publication of is 1 st July 2021. -

Chapter 3 the Work of National Military Tribunals Under Control Council Law 10

Chapter 3 The Work of National Military Tribunals under Control Council Law 10 Jackson Maogoto On 20 December 1945, the Allied Control Council promulgated Law No. 10 (CCL No. 10), which was to govern all further Nazi prosecutions in domestic courts.1 The law was the fulfilment of the vow made by the Allied Powers in the course of World War II to return war criminals so they could stand trial before tribunals in the ter- ritories in which their crimes had been committed.2 Many advances in enriching international jurisprudence and fleshing out the substantive content of international criminal law were made by post-World War II domestic tribunals in implementing the Nuremberg legacy. These national trials reaffirmed the triumph of international law over certain aspects of sovereignty. Literally thousands of trials were carried out in domestic tribunals in different countries and regions of the world subsequent to the Nuremberg and Tokyo international trials. CCL No. 10 was closely modelled on the Nuremberg Charter. Like the Nuremberg Charter, it abrogated the act of State doctrine3 and rejected superior orders as a defence.4 Prosecution was also not barred by any amnesty, immunity or pardon which may have been granted by the Nazi regime.5 It not only provided for a wide range of penalties for war crimes and crimes against humanity, but, like the Nuremberg Charter, 1 Allied Control Council Law No. 10, Punishment of Persons Guilty of War Crimes, Crimes against Peace and against Humanity (20 December 1945), Official Gazette of the Control Council for Germany, No 3, Berlin, 31 January 1946 (‘CCL No. -

The Berlin Blockade and the Airlift of 1948/1949

The Berlin Blockade and the Airlift of 1948/1949 Almost seventy years ago, from 26 June 1948 to 30 September 1949, the sound of Allied aircraft overhead day and night was audible proof for the people of Berlin that America, Great Britain, and France were standing up to the Soviet blockade that threatened the city’s freedom. Taking a look back at the first Berlin crisis illuminates some basic facts that are fundamental to understanding the political situation in today’s unified city. The four victorious powers had agreed already during World War II to divide Germany into four zones and to make Greater Berlin a quadripartite administrative area. The zones to the west were occupied by the United States, Great Britain, and France, while the Soviet Union took the zone to the east. In each of those zones, ultimate authority lay with the zone’s military government. Berlin, located inside the Soviet zone about 180 km from that zone’s western border, was divided into four sectors headed by the city commandants of each occupying power. An Allied Kommandatura made up of the four city commandants was to be jointly responsible for Berlin as a whole. There were serious differences even on the subject of political geography: according to the Soviets, Germany’s capital city was located “on the territory of the Soviet zone” (which later became the GDR), while the Western powers saw Berlin as an area under joint four-power administration that was surrounded by the Soviet zone. This crucial question of legal status initially had little relevance to the everyday lives of the people of Berlin, who were busy rebuilding those lives amid the ruins of their city. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

839 Was Also a Conservative Romantic, a Trait That Became Particularly Pronounced in His Second World War Columns

Comptes rendus / Book Reviews 839 was also a conservative romantic, a trait that became particularly pronounced in his Second World War columns. Writing of British naval valour, he proclaimed that “the spirit of Elizabethan days has come back to these islands once more.” (p. 131) His tone became more muted after the war, when the Labour Party which he despised came to power and implemented many of the provisions of the 1942 Beveridge Report. Baxter was vehemently opposed to socialism and the welfare state, siding decisively with the former in what he called the “battle of the individual against the state” (p. 242). His most evocative columns, however, such as that on the 1936 Abdication crisis, brought home to Canadians those events gripping what many still saw as the “mother dominion.” If I had one reservation about the book, it is that Baxter and the Canadian connection sometimes fades from view as Thompson sets out the context of successive British high political dramas. More might also be said about how, and in what ways, the ideas and sentiments Baxter espoused in his London Letters were received by his Maclean’s readers. Thompson gives us circulation numbers which attest to the magazine’s self-proclaimed status as “Canada’s National Magazine,” but how Baxter’s ideas shaped Canadians’ political, economic, social and cultural activities is left mostly unsaid. Nonetheless, this is a fine book, closely researched and carefully written. It is particularly strong on Baxter during the appeasement years, reflecting Thompson’s expertise in this period. Historians of the British world would benefit greatly from more transnational studies in the model of Thompson’s work on Beverley Baxter. -

2020 Applus Services S.A., Financial Statements

Applus Services, S.A. Financial Statements for the year ended 31 December 2020 and Directors' Report, together with Independent Auditor's Report Translation of a report originally issued in Spanish based on our work performed in accordance with the audit regulations in force in Spain and of financial statements originally issued in Spanish and prepared in accordance with the regulatory financial reporting framework applicable to the Company in Spain (see Notes 2 and 14). In the event of a discrepancy, the Spanish-language version prevails. This declaration is a translation for informative purposes only of the original document issued in Spanish, which has been signed for approval by every Board member. In the event of discrepancy, the Spanish- language version prevails. The members of the Board of Directors of Applus Services, S.A. declare that, to the best of their knowledge, the individual financial statements of Applus Services, S.A. (comprising the statement of financial position, statement of profit or loss, the statement of changes in equity, the statement of cash flows and the explanatory notes) for the year ended at 31 December 2020, prepared in accordance with the accounting policies applicable and approved by the Board of Directors at its meeting on 18 February 2021, present fairly the equity, financial position and results of Applus Services, S.A., and that the management report accompanying such financial statements includes a fair analysis of the business’ evolution, results and the financial position of Applus Services, S.A, as well as a description of the principal risks and uncertainties that the company faces. -

Filming the End of the Holocaust War, Culture and Society

Filming the End of the Holocaust War, Culture and Society Series Editor: Stephen McVeigh, Associate Professor, Swansea University, UK Editorial Board: Paul Preston LSE, UK Joanna Bourke Birkbeck, University of London, UK Debra Kelly University of Westminster, UK Patricia Rae Queen’s University, Ontario, Canada James J. Weingartner Southern Illimois University, USA (Emeritus) Kurt Piehler Florida State University, USA Ian Scott University of Manchester, UK War, Culture and Society is a multi- and interdisciplinary series which encourages the parallel and complementary military, historical and sociocultural investigation of 20th- and 21st-century war and conflict. Published: The British Imperial Army in the Middle East, James Kitchen (2014) The Testimonies of Indian Soldiers and the Two World Wars, Gajendra Singh (2014) South Africa’s “Border War,” Gary Baines (2014) Forthcoming: Cultural Responses to Occupation in Japan, Adam Broinowski (2015) 9/11 and the American Western, Stephen McVeigh (2015) Jewish Volunteers, the International Brigades and the Spanish Civil War, Gerben Zaagsma (2015) Military Law, the State, and Citizenship in the Modern Age, Gerard Oram (2015) The Japanese Comfort Women and Sexual Slavery During the China and Pacific Wars, Caroline Norma (2015) The Lost Cause of the Confederacy and American Civil War Memory, David J. Anderson (2015) Filming the End of the Holocaust Allied Documentaries, Nuremberg and the Liberation of the Concentration Camps John J. Michalczyk Bloomsbury Academic An Imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc LONDON • OXFORD • NEW YORK • NEW DELHI • SYDNEY Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2014 Paperback edition fi rst published 2016 © John J. -

Suggested Search Terms for Records on Nazi-Era Cultural Property

Suggested search terms for records on Nazi-era cultural property A Artist Aachen Art objects Advance reparation deliveries Austria Ahnenerbe Axis Alfred Rosenberg Axis Victims League Allied commission for Austria Assets Allied expeditionary force Allied kommandatura berlin B Allied high commission for Germany Beaux arts Alt aussee Behr, Kurt von American commission for the protection of artistic and historic Belgium monuments in Europe Belongings American council of learned societies Berlin Amsterdam art society Board of Review Anglo-Jewish Association Board of Deputies of British Jews Antiques Bonds Archive Book Art Booty Boymans museum, Rotterdam Convention for the protection of historic buildings and works of British museum art in time of war Brueghel Cooper, Douglas Buende Cranach Bunjes papers Credit Business Cultural objects Cultural property C Currency Carpet Custodian Central British Fund for Jewish Relief Central collecting point D Cézanne Damage Chagall Dealer Chateau Debt China Delivery Churchill, Winston Denkmalpflege Claim Depository Claimant Devisenschutzkommando [foreign currency control] Client Directorate of civil affairs Coins Dispossessed Collecting point Dispossession Commission for the protection and restitution of cultural Drawing materials Dresden Company Duerer Concentration camp Durer Conference of allied ministers of education Control commission for Germany E Control commission for Austria Enemy Control office for Germany and Austria Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg Err European advisory -council Historic building