University of London Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Margin Requirements Across Equity-Related Instruments: How Level Is the Playing Field?

Fortune pgs 31-50 1/6/04 8:21 PM Page 31 Margin Requirements Across Equity-Related Instruments: How Level Is the Playing Field? hen interest rates rose sharply in 1994, a number of derivatives- related failures occurred, prominent among them the bankrupt- cy of Orange County, California, which had invested heavily in W 1 structured notes called “inverse floaters.” These events led to vigorous public discussion about the links between derivative securities and finan- cial stability, as well as about the potential role of new regulation. In an effort to clarify the issues, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston sponsored an educational forum in which the risks and risk management of deriva- tive securities were discussed by a range of interested parties: academics; lawmakers and regulators; experts from nonfinancial corporations, investment and commercial banks, and pension funds; and issuers of securities. The Bank published a summary of the presentations in Minehan and Simons (1995). In the keynote address, Harvard Business School Professor Jay Light noted that there are at least 11 ways that investors can participate in the returns on the Standard and Poor’s 500 composite index (see Box 1). Professor Light pointed out that these alternatives exist because they dif- Peter Fortune fer in a variety of important respects: Some carry higher transaction costs; others might have higher margin requirements; still others might differ in tax treatment or in regulatory restraints. The author is Senior Economist and The purpose of the present study is to assess one dimension of those Advisor to the Director of Research at differences—margin requirements. -

Morning Briefing Global Economic Trading Calendar

A Eurex publication focused on European financial markets, produced by MNl Morning Briefing March 12h 2015 Thursday sees a full day of data, with Council Member KlaasKnot speaks and be up 0.4%also excluding the German and French final inflation in Amsterdam. gasoline station sales. numbers the early feature. EMU data at 1000GMT sees the The US January business At 0700GMT, the German final January industrial output numbers inventories data will cross the wires February harmonised inflation data cross the wires. at 1400GMT. will be published. to be followed by the French numbers at 0745GMT Across the Atlantic, the calendar gets The value of business inventories is and the Spanish data at 0800GMT. underway at 1230GMT, with the expected to fall 0.2% in January after release of the February retail sales, small gains in recent months. ECB Executive Board Member February import/export index and the Benoit Coeure will deliver a speech jobless claims data for the March 7 Late data sees the US February on the future of euro area week. Treasury Statement set for release at investment, quantitative easing, and 1800GMT and Greek debt, in Paris, starting The level of initial jobless claims is at0745GMT. expected to fall by 12,000 to 308,000 the M2 money supply data for the in the March 7 week after rising by Mar 2 week at 2030GMT. Then, at 0915GMT, ECB Governing 7,000 in the previous week. The four- Council Member Jens Weidmann will week moving average rose by The U.S. Treasury is expected to hold a press conference, in 10,250 to 304,750 in the February 28 post a $188.5 billion budget deficit Frankfurt. -

Gambling Act 2005

Gambling Act 2005 CHAPTER 19 CONTENTS PART 1 INTERPRETATION OF KEY CONCEPTS Principal concepts 1 The licensing objectives 2 Licensing authorities 3Gambling 4 Remote gambling 5 Facilities for gambling Gaming 6 Gaming & game of chance 7Casino 8 Equal chance gaming Betting 9 Betting: general 10 Spread bets, &c. 11 Betting: prize competitions 12 Pool betting 13 Betting intermediary Lottery 14 Lottery 15 National Lottery ii Gambling Act 2005 (c. 19) Cross-category activities 16 Betting and gaming 17 Lotteries and gaming 18 Lotteries and betting Miscellaneous 19 Non-commercial society PART 2 THE GAMBLING COMMISSION 20 Establishment of the Commission 21 Gaming Board: transfer to Commission 22 Duty to promote the licensing objectives 23 Statement of principles for licensing and regulation 24 Codes of practice 25 Guidance to local authorities 26 Duty to advise Secretary of State 27 Compliance 28 Investigation and prosecution of offences 29 Licensing authority information 30 Other exchange of information 31 Consultation with National Lottery Commission 32 Consultation with Commissioners of Customs and Excise PART 3 GENERAL OFFENCES Provision of facilities for gambling 33 Provision of facilities for gambling 34 Exception: lotteries 35 Exception: gaming machines 36 Territorial application Use of premises 37 Use of premises 38 Power to amend section 37 39 Exception: occasional use notice 40 Exception: football pools Miscellaneous offences 41 Gambling software 42 Cheating 43 Chain-gift schemes 44 Provision of unlawful facilities abroad Gambling Act 2005 (c. 19) iii PART 4 PROTECTION OF CHILDREN AND YOUNG PERSONS Interpretation 45 Meaning of “child” and “young person” Principal offences 46 Invitation to gamble 47 Invitation to enter premises 48 Gambling 49 Entering premises 50 Provision of facilities for gambling Employment offences 51 Employment to provide facilities for gambling 52 Employment for lottery or football pools 53 Employment on bingo and club premises 54 Employment on premises with gaming machines 55 Employment in casino, &c. -

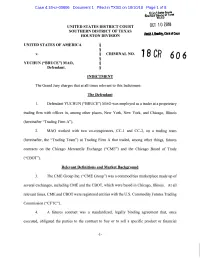

Mao Indictment

Case 4:18-cr-00606 Document 1 Filed in TXSD on 10/10/18 Page 1 of 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT OCT 1 0 2018 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS HOUSTON DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA § § v. § CRIMINAL NO. § 18 CR 60 6 YUCHUN ("BRUCE") MAO, § Defendant. § INDICTMENT The Grand Jury charges that at all times relevant to this Indictment: The Defendant 1. Defendant YUCHUN ("BRUCE") MAO was employed as a trader at a proprietary trading firm with offices in, among other places, New York, New York, and Chicago, Illinois (hereinafter "Trading Firm A"). 2. MAO worked with two co-conspirators, CC-1 and CC-2, on a trading team (hereinafter, the "Trading Team") at Trading Firm A that traded, among other things, futures contracts on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange ("CME") and the Chicago Board of Trade ("CBOT"). Relevant Definitions and Market Background 3. The CME Group Inc. ("CME Group") was a commodities marketplace made up of several exchanges, including CME and the CBOT, which were based in Chicago, Illinois. At all relevant times, CME and CBOT were registered entities with the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission ("CFTC"). 4. A futures contract was a standardized, legally binding agreement that, once executed, obligated the parties to the contract to buy or to sell a specific product or financial -1- Case 4:18-cr-00606 Document 1 Filed in TXSD on 10/10/18 Page 2 of 8 instrument in the future. That is, the buyer and seller of a futures contract agreed on a price today for a product or financial instrument to be delivered (by the seller), in exchange for money (to be provided by the buyer), on a future date. -

Briefing.Com

PORTFOLIO STRATEGY | PUBLISHED BY RAYMOND JAMES & ASSOCIATES Michael Gibbs, Director of Equity Portfolio & Technical Strategy | (901) DECEMBER 9, 2020 | 9:02 AM EST 579-4346 | [email protected] Joey Madere, CFA | (901) 529-5331 | [email protected] Richard Sewell, CFA | (901) 524-4194 | [email protected] Mitch Clayton, CMT, Senior Technical Analyst | (901) 579-4812 | [email protected] Morning Brew - December 9, 2020 U.S. FUTURES (BRIEFING.COM) The S&P 500 futures trade five points, or 0.1%, above fair value following yesterday's record closes in the benchmark index, Nasdaq Composite, and Russell 2000. Stimulus developments have been of interest this morning. Briefly, Treasury Secretary Mnuchin offered a new $916 billion stimulus bill that includes $600 direct payments to Americans but no enhanced unemployment benefits. The bill is slightly larger than the $908 billion bipartisan bill that excludes direct payments but includes unemployment relief. Democratic Congressional leadership called it progress, according to Bloomberg, but reiterated the need for unemployment relief and said talking points should still be focused on the bipartisan plan. They also shot down Senate Majority Leader McConnell's suggestion of leaving out funding for state and local governments. When the market opens for trading, attention will divert back to equities for the DoorDash (DASH) IPO, which priced shares at $102.00 for a $38.7 billion valuation on a fully-diluted basis. On the data front, investors will receive the JOLTS - Job Openings report for October and Wholesale Inventories for October (Briefing.com consensus 0.9%) at 10:00 a.m. -

CME Group and Nasdaq Extend Exclusive Nasdaq-100 Futures License Through 2029

October 1, 2018 CME Group and Nasdaq Extend Exclusive Nasdaq-100 Futures License Through 2029 Nasdaq futures and options on futures trade an average of 437,000-plus contracts each day, an increase of 52 percent year-to-date CHICAGO, Oct. 1, 2018 /PRNewswire/ -- CME Group and Nasdaq today announced a ten-year extension of CME Group's exclusive license to offer futures and options on futures based on the Nasdaq-100 and other Nasdaq indexes, through 2029. As the world's leading and most diverse derivatives marketplace, CME Group operates the largest equity index futures complex in the world. Nasdaq is a leading global provider of trading, clearing, exchange technology, listing, information and public company services. "We are extremely pleased to extend our exclusive licensing agreement with Nasdaq, said CME Group Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Terry Duffy. "Building on more than 20 years of partnership, this agreement will ensure market participants worldwide will continue to have seamless access to our suite of Nasdaq products, allowing them to manage risk or gain exposure to the 100 largest non-financial companies. Customers also benefit from capital efficiencies by trading alongside our industry-leading equity index products." "The Nasdaq-100 has been a top performing large cap growth index over the last ten years and has been providing investors with access to the world's most innovative companies, including Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Alphabet, Intel, Microsoft, and Starbucks among many others," said Adena Friedman, President and CEO of Nasdaq. "We have been partners with CME Group for more than 20 years and extending our relationship enables market participants access to our global benchmark products in order to manage their equity market risk." In 1982, CME Group pioneered futures trading on equity indices. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 39/Thursday, February 27, 2020

11596 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 39 / Thursday, February 27, 2020 / Proposed Rules COMMODITY FUTURES TRADING All comments must be submitted in F. § 150.8—Severability COMMISSION English, or if not, be accompanied by an G. § 150.9—Process for Recognizing Non- English translation. Comments will be Enumerated Bona Fide Hedging 17 CFR Parts 1, 15, 17, 19, 40, 140, 150, posted as received to https:// Transactions or Positions With Respect and 151 to Federal Speculative Position Limits comments.cftc.gov. You should submit H. Part 19 and Related Provisions— RIN 3038–AD99 only information that you wish to make Reporting of Cash-Market Positions available publicly. If you wish the I. Removal of Part 151 Position Limits for Derivatives Commission to consider information III. Legal Matters that you believe is exempt from A. Introduction AGENCY: Commodity Futures Trading disclosure under the Freedom of B. Key Statutory Provisions Commission. Information Act (‘‘FOIA’’), a petition for C. Ambiguity of Section 4a With Respect ACTION: Proposed rule. to Necessity Finding confidential treatment of the exempt D. Resolution of Ambiguity SUMMARY: The Commodity Futures information may be submitted according E. Evaluation of Considerations Relied Trading Commission (‘‘Commission’’ or to the procedures established in § 145.9 Upon by the Commission in Previous 1 ‘‘CFTC’’) is proposing amendments to of the Commission’s regulations. Interpretation of Paragraph 4a(a)(2) regulations concerning speculative The Commission reserves the right, F. Necessity Finding but shall have no obligation, to review, G. Request for Comment position limits to conform to the Wall IV. Related Matters Street Transparency and Accountability pre-screen, filter, redact, refuse, or remove any or all submissions from A. -

Regulating Gaming in Ireland

12 774406 4 77 4 56 00352 52 235 6 4 3 4 3 23284 1983 7 50 218395 7 4 4 74 45311 35 452 23 2 6 7 0 1119 7502 4 21 577 5 9 5 45 10035 45 423 22 6 7 3 2 52328 1198 4 75 420 9 3 7 93 49 03496 57 34 70 2 3 7 1 56738 950 6 80 58015 5 3 20 46 32343 02 23 11 8 4 2 9 38751 454978 0 67857 3 0 70 20 0709 10 Regulating Gaming in Ireland 73 95 4 8 4 58345 264647 3 39002 2 2 11 83 02342 98 75 45 7 0 9 34068 912035 6 08110 738 95 468 94580 64 34 4 0 9 0 6904 026 0 4 5 50103 053 54 34 100 25 3 13455 01 5 1 50134 040054 5 8 3789 4250432 46 0435 81 75804 59 8 3 89985 407007 86 8972 7076121 37 7043 37 5 82734 54 1 8 01364 034285 31 286 1424504 97 34967 79034 09120 56 0 1 67380 501468 01 583 2064980 7 60540 690467 60043 52 1 2 21540 425501 50 250 4550013 5 41501 455040 56807Regulating78 3 0 Gaming55469 043507 43 580 5978802 1 985424070070 4945 15 5 5 64647 234390 28 19 7502342 9 5193454 800 7857 340in8 Ireland1 56070 811056 50 680 5801564 34 2646473 343 35232 411 9 7 34200 387519 80 496 57 03406 09 35 709 11056 80095 146 0 5 56458 520649 50 054 469 46798 60 45 010 205321540034 550 0 5 13425 345500 11 150 345 0400 56 37 834 043255469760 350 6 5 19758 6597880 1488 854 407 0705 48 0 761 053768270437 837 2 3 73455 4134582 1364 034 850 3145 07 1 567 8009501468009 580 5 8 20264 7332343 2352 841 198 4750 20 7 193 5497800349678 790 4 7 20356 0908158 5978 213 488 9854 70 67489 2707076121053Report of the Casino Committee 682 0 9 42504358273455 1345 070 364 7034 0731 28675 4245047497800 496 8Report90 of the68709120356070 1105 380 950 4680 5801 58345 0649801973501 054Casino4 -

Before the Bell Morning Market Brief

Before the Bell Morning Market Brief May 13, 2021 MORNING MARKET COMMENTARY: Anthony M. Saglimbene, Global Market Strategist Quick Take: U.S. stock futures pointing to a higher open; European markets are trading mostly lower; Asia ended down overnight; West Texas Intermediate (WTI) oil trading at $64.45; 10-year U.S. Treasury yield at 1.69%. Markets Churn As "Hotter" Inflation Sparks Growth Concerns: Yesterday, stock prices fell across the board, as rising inflation levels in April spooked already jittery investors. The NASDAQ Composite (down 2.7% on the day) and Growth stocks more broadly took it on the chin. Inflation levels last month looked much hotter than most expected (more on that below), prompting a further push into cyclical value stocks at the expense of Technology/Growth areas. While the market was broadly lower yesterday, the trend of cyclical value outperformance continued to mitigate overall declines on Wednesday. The Dow Jones Industrials Average (down 2.0%) and several value-based sectors were lower yesterday but did hold up better than the NASDAQ. As the FactSet chart below shows, the Dow has seen a generally consistent trend higher this year (until recently) — driven by a more concentrated exposure to cyclical value areas of the market. These value areas are seen as more leveraged to strengthening reopening trends and less impacted by rising inflation levels over the near term. In February, the NASDAQ turned sharply lower on inflation/interest rate fears, while the Dow was able to push higher and eventually create performance separation on the heels of a strengthening recovery. -

Imperial Laws Application Bill-98-1

IMPERIAL LAWS APPLICATION BILL NOTE THIS Bill is being introduced in its present form so as to give notice of the legislation that it foreshadows to Parliament and to others whom it may concern, and to provide those who may be interested with an opportunity to make representations and suggestions in relation to the contemplated legislation at this early formative stage. It is not intended that the Bill should pass in its present form. Work towards completing and polishing the draft, and towards reviewing the Imperial enactments in force in New Zealand, is proceeding under the auspices of the Law Reform Council. It is intended to introduce a revised Bill in due course, and to allow ample time for study of the revised Bill and making representations thereon. The enactment of a definitive statutory list of Imperial subordinate legis- lation in force in New Zealand is contemplated. This list could appropriately be included in the revised Bill, but this course is not intended to be followed if it is likely to cause appreciable delay. Provision for the additional list can be made by a separate Bill. Representations in relation to the present Bill may be made in accordance with the normal practice to the Clerk of the Statutes Revision Committee of tlie House of Representatives. No. 98-1 Price $2.40 IMPERIAL LAWS APPLICATION BILL EXPLANATORY NOTE THIS Bill arises out of a review that is in process of being made by the Law Reform Council of the Imperial enactments in force in New Zealand. The intention is that in due course the present Bill will be allowed to lapse, and a complete revised Bill will be introduced to take its place. -

The Regulation of Financial Product Innovation Typified by Bitcoin-Based Derivative Contracts

2018-2019 FINANCIAL PRODUCT INNOVATION 765 THE REGULATION OF FINANCIAL PRODUCT INNOVATION TYPIFIED BY BITCOIN-BASED DERIVATIVE CONTRACTS DR. GIOVANNI PATTI* Abstract If Bitcoin and blockchain epitomize financial “product” and financial “process” innovation, respectively, the new innovative trend does not stop with Bitcoin and blockchain themselves. Bitcoin now represents an asset that offers the basis for the further development of financial “product” innovation through derivative contracts. The presence in the American financial markets of several types of Bitcoin- based derivative contracts, such as Bitcoin non-deliverable forwards, Bitcoin options, Bitcoin futures, and Bitcoin binary options is a clear signal of the new trend. It is notorious that one factor that has favored the creation and development of a market for Bitcoin-based derivative contracts is the attempt by the American-regulated derivative markets to attract the investment interests of institutional investors. Although Bitcoin-based derivative contracts offer the opportunity to gain exposure to the underlying asset through regulated designated contract markets (DCMs) and swap execution facilities (SEFs), they do not completely shield investors from some typical risks inherent in Bitcoin. Thus, there could be room for regulators to step in and support Bitcoin derivative markets in mitigating those risks. The present article aims to shed light on those risks and to suggest some regulatory interventions to mitigate them. The American Bitcoin derivative markets use different mechanisms for the determination of the reference price. These mechanisms present differences that are, in some cases, significant. Competition between derivative markets will likely lead to the natural selection of those markets with the most reliable mechanisms. -

Nasdaq 100 Futures: 5 Key Facts to Know Before Trading

Nasdaq 100 Futures: 5 Key Facts to Know Before Trading The Nasdaq 100 futures are part of the index futures contracts offered by the CME Group. They are one of the popular index futures with different versions, but the e-mini Nasdaq 100 futures tops the list in terms of volume and popularity. Similar to the E-mini S&P500 or the $5 Dow futures the Nasdaq 100 futures contract tracks one of the leading stock indexes in the U.S., namely the Nasdaq 100 index. Compared to the S&P500 e-mini (ES) index futures contracts, the e-mini Nasdaq 100 contracts are a bit cheaper when you compare the tick value. For example, a 0.25 index point move in S&P500 is valued at $12.50, while the tick value for the e- mini Nasdaq 100 contract is $5.00. The Nasdaq 100 futures contracts also exhibit some characteristics which sets it apart from the other index futures contracts. Besides some fundamental and technical differences, the Nasdaq 100 futures contracts allows day traders and investors to trade the contracts with relative ease, either for speculative purposes or to hedge the risks from the underlying market. The Nasdaq 100 futures contracts are all financially settled and there is no physical delivery of the underlying asset. (NQ) – The Nasdaq 100 Futures Price Chart Besides futures, traders can also gain exposure to the underlying market via options contracts as well. Although the Nasdaq 100 futures contracts might look similar to other index futures contracts, there are some subtle differences that set it apart.