America's First Ladies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of the Image of the First Lady

The Evolution of the Image of the First Lady Reagan N. Griggs Dr. Rauhaus University of North Georgia The role of the First Lady of the United States of America has often been seen as symbolic, figurative, and trivial. Often in comparison to her husband, she is seen as a minimal part of the world stage and ultimately of the history books. Through this research, I seek to debunk the theory that the First Lady is just an allegorical figure of our country, specifically through the analysis of the twenty- first century first ladies. I wish to pursue the evolution of the image of the First Lady and her relevance to political change and public policies. Because a woman has yet to be president of the United States, the First Lady is arguably the only female political figure to live in the White House thus far. The evolution of the First Lady is relevant to gender studies due to its pertinence to answering the age old question of women’s place in politics. Every first lady has in one way or another, exerted some type of influence on the position and on the man to whom she was married to. The occupants of the White House share a unique partnership, with some of the first ladies choosing to influence the president quietly or concentrating on the hostess role. While other first ladies are seen as independent spokeswomen for their own causes of choice, as openly influencing the president, as well as making their views publicly known (Carlin, 2004, p. 281-282). -

American First Ladies As Goodwill Ambassadors

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research Hunter College 2010 American First Ladies as Goodwill Ambassadors Wendy W. Tan CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_pubs/12 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] American First Ladies as Goodwill Ambassadors: Summaries after studying materials available in Presidential Libraries By Wendy Tan Head of Cataloging, Hunter College Libraries, the City University of NY 695 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10065 Abstract Quite a few First Ladies took very active moves regarding international interests, and they often weighed in their opinions on their husbands’ decisions on related issues. My research was mainly conducted in five Presidential Libraries associated with five well-traveled First Ladies. After studying hundreds of journeys they made, my descriptions were focused on five, one for each lady, of them only. All of these trips shared a common trait, which was under the calling of humanitarian cause. Key Words American First Ladies; Goodwill Ambassadors; American Women 2 Introduction According to Gallup’s poll (2001) for the category of “most admired women”, 1948-1961 was Eleanor Roosevelt; 1962-1966 Jacqueline Kennedy; 1971-1973 Pat Nixon; 1977-1980 Rosalynn Carter; 1993-2000 Hillary Clinton. One of the qualifications shared by all these winners is that they were the First Ladies during much of those periods. Another characteristic present among these First Ladies is that they actively participated in activities taking place in foreign lands. -

Presidents' Day Family

Schedule at a Glance Smith Center Powers Room Learning Center The Pavilion Exhibit Galleries Accessibility: Performances Hands-on | Crafts Performances | Activities “Make and Take” Craft Activities Special Activities Learning Wheelchairs are available Shaping A New Nation Suffrage Centennial Center at the Visitor Admission 10:00 Desk on a first come, first served basis. Video Popsicle presentations in the Museum Stick Flags 10:30 Mini RFK 10:00 – 11:00 Foyer Elevators are captioned for visitors John & Abigail Adams WPA Murals Smith Center who are deaf or hard 10:30 – 11:10 Suffragist 10:00 – 11:30 Kennedy Scrimshaw of hearing. 11:00 Read Aloud Sashes & Campaign Hats 10:30 – 11:30 10:45 – 11:15 Sunflowers & Buttons James & Dolley Madison 10:00 – 12:30 10:00 – 12:15 Powers Café 11:30 11:10 – 11:50 Colonial Clothes Lucretia Mott Room 11:00 – 12:15 11:15 – 11:40 Adams Astronaut Museum Tour 11:15 – 12:20 Helmets 11:30 – 12:15 12:00 Eleanor Roosevelt 11:15 – 12:30 Restrooms 11:50 – 12:30 PT 109 Cart 12:30 Sojourner Truth Protest Popsicle 12:00 – 1:00 Presidential Press Conference 12:15 – 1:00 Posters Stick Flags 12:30 – 1:00 Museum Evaluation Station Presidential 12:00 – 1:30 12:00 – 1:30 Homes Store 1:00 James & Dolley Madison 12:30 – 1:30 Pavilion Adams Letter Writing 1:00 – 1:30 Astronaut Museum 1:00 – 1:40 to the President Space Cart Lucretia Mott Helmets Lobby 12:30 – 2:15 1:00 – 2:00 1:30 Eleanor Roosevelt 1:15 – 1:45 1:00 – 2:00 Entrance 1:30 – 2:00 2:00 John & Abigail Adams Sojourner Truth 2:00 – 2:30 2:00-2:30 Museum Tour Zines Scrimshaw 2:00 – 2:45 1:00 – 3:30 Mini 2:00 – 3:00 Sensory 2:30 Powerful Women Jeopardy WPA Murals Accommodations: 2:30 – 3:00 2:00 – 3:30 Kennedy The John F. -

**** This Is an EXTERNAL Email. Exercise Caution. DO NOT Open Attachments Or Click Links from Unknown Senders Or Unexpected Email

Scott.A.Milkey From: Hudson, MK <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, June 20, 2016 3:23 PM To: Powell, David N;Landis, Larry (llandis@ );candacebacker@ ;Miller, Daniel R;Cozad, Sara;McCaffrey, Steve;Moore, Kevin B;[email protected];Mason, Derrick;Creason, Steve;Light, Matt ([email protected]);Steuerwald, Greg;Trent Glass;Brady, Linda;Murtaugh, David;Seigel, Jane;Lanham, Julie (COA);Lemmon, Bruce;Spitzer, Mark;Cunningham, Chris;McCoy, Cindy;[email protected];Weber, Jennifer;Bauer, Jenny;Goodman, Michelle;Bergacs, Jamie;Hensley, Angie;Long, Chad;Haver, Diane;Thompson, Lisa;Williams, Dave;Chad Lewis;[email protected];Andrew Cullen;David, Steven;Knox, Sandy;Luce, Steve;Karns, Allison;Hill, John (GOV);Mimi Carter;Smith, Connie S;Hensley, Angie;Mains, Diane;Dolan, Kathryn Subject: Indiana EBDM - June 22, 2016 Meeting Agenda Attachments: June 22, 2016 Agenda.docx; Indiana Collaborates to Improve Its Justice System.docx **** This is an EXTERNAL email. Exercise caution. DO NOT open attachments or click links from unknown senders or unexpected email. **** Dear Indiana EBDM team members – A reminder that the Indiana EBDM Policy Team is scheduled to meet this Wednesday, June 22 from 9:00 am – 4:00 pm at IJC. At your earliest convenience, please let me know if you plan to attend the meeting. Attached is the meeting agenda. Please note that we have a full agenda as this is the team’s final Phase V meeting. We have much to discuss as we prepare the state’s application for Phase VI. We will serve box lunches at about noon so we can make the most of our time together. -

Georgian Court University Fall/Winter 2018 Magazine

Volume 16 | Number 1 Fall/Winter 2018 Georgian Court University Magazine President’s Annual Report & Honor Roll of Donors 2017–2018 Georgian Court–Hackensack Meridian Health School of Nursing Celebrates 10 Years From the President Dear Alumni, Donors, Students, and Friends: Happy New Year! The holiday season is behind us, but the activities and accolades of 2018 still give us to plenty to celebrate. That is why this edition of GCU Magazine is packed with examples of good news worth sharing—with you and with those you know. First, the Georgian Court–Hackensack Meridian Health School of Nursing is celebrating its 10-year anniversary. Our first decade has produced successful health care professionals serving patients from coast to coast, and the program is among the fastest growing at GCU. In this issue of the magazine, I’d like you to meet two unforgettable alumni. Florence “Riccie” Riccobono Johnson ’45 (pp. 28–29) has worked at CBS for more than six decades and reflects on her time at 60 Minutes, where she’s been employed since 1968. Gemma Brennan ’84, ’93 (pp. 6–9), a longtime teacher, principal, and part-time GCU professor, is sharing her passion in unique ways. Likewise, our newest honorary degree recipient, His Royal Highness The Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex, shared his passion for court tennis during a September visit to GCU (p. 13). Georgian Court was at its absolute finest as the prince met students, faculty, staff, and coaches, and played several matches in the Casino. A few weeks later, I was proud to see alumni join in the fun of Reunion and Homecoming Weekend 2018 (p. -

Preserving, Displaying, and Insisting on the Dress: Icons, Female Agencies, Institutions, and the Twentieth Century First Lady

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2009 Preserving, Displaying, and Insisting on the Dress: Icons, Female Agencies, Institutions, and the Twentieth Century First Lady Rachel Morris College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Morris, Rachel, "Preserving, Displaying, and Insisting on the Dress: Icons, Female Agencies, Institutions, and the Twentieth Century First Lady" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 289. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/289 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Preserving, Displaying, and Insisting on the Dress: Icons, Female Agencies, Institutions, and the Twentieth Century First Lady A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in American Studies from the College of William and Mary in Virginia. Rachel Diane Morris Accepted for ________________________________ _________________________________________ Timothy Barnard, Director _________________________________________ Chandos Brown _________________________________________ Susan Kern _________________________________________ Charles McGovern 2 Table of -

Ranking America's First Ladies Eleanor Roosevelt Still #1 Abigail Adams Regains 2 Place Hillary Moves from 2 to 5 ; Jackie

For Immediate Release: Monday, September 29, 2003 Ranking America’s First Ladies Eleanor Roosevelt Still #1 nd Abigail Adams Regains 2 Place Hillary moves from 2 nd to 5 th ; Jackie Kennedy from 7 th th to 4 Mary Todd Lincoln Up From Usual Last Place Loudonville, NY - After the scrutiny of three expert opinion surveys over twenty years, Eleanor Roosevelt is still ranked first among all other women who have served as America’s First Ladies, according to a recent expert opinion poll conducted by the Siena (College) Research Institute (SRI). In other news, Mary Todd Lincoln (36 th ) has been bumped up from last place by Jane Pierce (38 th ) and Florence Harding (37 th ). The Siena Research Institute survey, conducted at approximate ten year intervals, asks history professors at America’s colleges and universities to rank each woman who has been a First Lady, on a scale of 1-5, five being excellent, in ten separate categories: *Background *Integrity *Intelligence *Courage *Value to the *Leadership *Being her own *Public image country woman *Accomplishments *Value to the President “It’s a tracking study,” explains Dr. Douglas Lonnstrom, Siena College professor of statistics and co-director of the First Ladies study with Thomas Kelly, Siena professor-emeritus of American studies. “This is our third run, and we can chart change over time.” Siena Research Institute is well known for its Survey of American Presidents, begun in 1982 during the Reagan Administration and continued during the terms of presidents George H. Bush, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush (http://www.siena.edu/sri/results/02AugPresidentsSurvey.htm ). -

Abigail Adams As a Typical Massachusetts Woman at the Close of the Colonial Era

V/ax*W ad Close + K*CoW\*l ^V*** ABIGAIL ADAMS AS A TYPICAL MASSACHUSETTS WOMAN AT THE CLOSE OF THE COLONIAL ERA BY MARY LUCILLE SHAY THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS HISTORY COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AND SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1917 - UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS m^ji .9../. THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY ./?^..f<r*T) 5^.f*.l^.....>> .&*r^ ENTITLED IS APPROVED BY ME AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF i^S^«4^jr..^^ UA^.tltht^^ Instructor in Charge Approved :....<£*-rTX??. (QS^h^r^r^. lLtj— HEAD OF DEPARTMENT OF ZL?Z?.f*ZZS. 376674 * WMF ABIGAIL ARAMS AS A TYPICAL MASSACHUSETTS '.70MJEN AT THE CLOSE OP THE COLONIAL ERA Page. I. Introduction. "The Woman's Part." 1 II. Chapter 1. Domestic Life in Massachusetts at the Close of the Colonial Era. 2 III. Chapter 2. Prominent V/omen. 30 IV. Chapter 3. Abigail Adacs. 38 V. Bibliography. A. Source References 62 B. Secondary References 67 I Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/abigailadamsastyOOshay . 1 ABIJAIL ARAMS A3 A ISP1CAL MASSACHUSETTS .VOMAIJ aT THE GLOSS OF THE COLOHIAL SEA. I "The Woman's Part" It was in the late eighteenth century that Abigail Adams lived. It was a time not unlike our own, a time of disturbed international relations, of war. School hoys know the names of the heroes and the statesmen of '76, but they have never heard the names of the women. Those names are not men- tioned; they are forgotten. -

Speaker Listing

SPEAKER LISTING 2020-21 2010-11 Harrison Hickman ’75 | Peniel Joseph Majora Carter | David Brooks | President Bill Clinton John Avlon & Margaret Hoover (w/Mark Updegrove) Jeannette Walls | Jean-Michel Cousteau Ian Bremmer | Sally Field (w/Pat Mitchell) Paul Nicklen | Theresa May | Colson Whitehead 2009-10 Garry Trudeau | Yo-Yo Ma | Paul Krugman 2019-20 Anna Deavere Smith | David Gregory Laura Bush | Stephen Breyer Doris Kearns Goodwin (w/Mark Updegrove) 2008-09 Khaled Hosseini | Christiane Amanpour & James Rubin 2018-19 Sir Salman Rushdie | Anthony Bourdain @ DPAC Karl Rove & David Axelrod | Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Anna Quindlen Julia Gillard | Dr. Paul Farmer | Diana Nyad 2007-08 2017-18 Kathleen Turner, Louis Gossett Jr. & Jane Seymour Joe & Jill Biden | Lisa Genova | Leslie Odom Jr. Isabel Allende | J.C. Watts | Bob Woodward Reza Aslan | Ted Koppel | Brandon Stanton 2006-07 2016-17 Mary Robinson | David McCullough | Toni Morrison Michael Pollan | Mark & Scott Kelly | Amal Clooney Neil deGrasse Tyson | Bryan Stevenson | Alan Alda 2005-06 Karen Armstrong | Desmond Tutu | Bill Moyers 2015-16 *Garrison Keillor (2 shows) Robin Wright | Atul Gawande | Jon Meacham 2004 - 05 George Takei | Malcolm Gladwell Cokie Roberts | Mikhail Gorbachev | Mary Pipher 2014-15 Michael Beschloss Ron Howard (w/Leonard Maltin) | Bill Bryson 2003-04 Margaret Atwood (w/ Roger Rosenblatt) Dr. Sherwin Nuland | Edward Albee | Ken Burns Robert Reich | Anderson Cooper Sidney Poitier | George J. Mitchell 2013-14 2002-03 Robert Gates | Robert Ballard | Itzhak Perlman Ernest Gaines | Robert F. Kennedy Jr. Elizabeth Alexander | Steve Kroft and Lesley Stahl 2001-02 2012-13 Madeleine Albright | Oscar Arias and Ralph Nader Tina Brown | Tom Brokaw | Geoffrey Canada Bill Bradley, Jeb Bush and Gwen Ifill 2000-01 Thomas Friedman Doris Kearns Goodwin | Jack Miles | Bill Bradley Neil deGrasse Tyson 2011-12 Tony Blair | Twyla Tharp | Sanjay Gupta 1999 *David McCullough @ Reynolds Auditorium Colin Powell Ken Burns | Fareed Zakaria 1996 Thomas Friedman. -

Journalism 375/Communication 372 the Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture

JOURNALISM 375/COMMUNICATION 372 THE IMAGE OF THE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE Journalism 375/Communication 372 Four Units – Tuesday-Thursday – 3:30 to 6 p.m. THH 301 – 47080R – Fall, 2000 JOUR 375/COMM 372 SYLLABUS – 2-2-2 © Joe Saltzman, 2000 JOURNALISM 375/COMMUNICATION 372 SYLLABUS THE IMAGE OF THE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE Fall, 2000 – Tuesday-Thursday – 3:30 to 6 p.m. – THH 301 When did the men and women working for this nation’s media turn from good guys to bad guys in the eyes of the American public? When did the rascals of “The Front Page” turn into the scoundrels of “Absence of Malice”? Why did reporters stop being heroes played by Clark Gable, Bette Davis and Cary Grant and become bit actors playing rogues dogging at the heels of Bruce Willis and Goldie Hawn? It all happened in the dark as people watched movies and sat at home listening to radio and watching television. “The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture” explores the continuing, evolving relationship between the American people and their media. It investigates the conflicting images of reporters in movies and television and demonstrates, decade by decade, their impact on the American public’s perception of newsgatherers in the 20th century. The class shows how it happened first on the big screen, then on the small screens in homes across the country. The class investigates the image of the cinematic newsgatherer from silent films to the 1990s, from Hildy Johnson of “The Front Page” and Charles Foster Kane of “Citizen Kane” to Jane Craig in “Broadcast News.” The reporter as the perfect movie hero. -

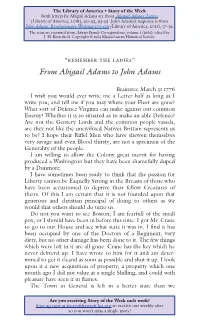

From Abigail Adams to John Adams

The Library of America • Story of the Week Both letters by Abigail Adams are from Abigail Adams: Letters (Library of America, 2016), 90–93, 93–95. John Adams’s response is from John Adams: Revolutionary Writings 1775–1783 (Library of America, 2011), 57–59. The texts are reprinted from Adams Family Correspondence, volume 1 (1963), edited by J. H. Butterfield. Copyright © 1963 Massachusetts Historical Society. “REMEMBER THE LADIES” From Abigail Adams to John Adams Braintree March 31 1776 I wish you would ever write me a Letter half as long as I write you; and tell me if you may where your Fleet are gone? What sort of Defence Virginia can make against our common Enemy? Whether it is so situated as to make an able Defence? Are not the Gentery Lords and the common people vassals, are they not like the uncivilized Natives Brittain represents us to be? I hope their Riffel Men who have shewen themselves very savage and even Blood thirsty; are not a specimen of the Generality of the people. I am willing to allow the Colony great merrit for having produced a Washington but they have been shamefully duped by a Dunmore. I have sometimes been ready to think that the passion for Liberty cannot be Eaquelly Strong in the Breasts of those who have been accustomed to deprive their fellow Creatures of theirs. Of this I am certain that it is not founded upon that generous and christian principal of doing to others as we would that others should do unto us. Do not you want to see Boston; I am fearfull of the small pox, or I should have been in before this time. -

CHRONOLOGY of WOMEN's SUFFRAGE 1776 Abigail Adams

CHRONOLOGY of WOMEN'S SUFFRAGE 1776 Abigail Adams writes to her husband, John Adams, asking him to "remember the ladies" in the new code of laws. Adams replies the men will fight the "despotism of the petticoat. Thus begins the long fight for Women's suffrage. 1869 Wyoming Territory grants suffrage to women 1870 Utah Territory grants suffrage to women 1880 New York State grants school suffrage to women 1890 Wyoming joins the Union as the first state with voting rights for women. By 1900 women also have full suffrage in Utah, Colorado and Idaho. New Zealand is the first nation to give women suffrage 1902 Women of Australia are enfranchised. 1906 Women of Finland are enfranchised. 1912 Suffrage referendums are passed in Arizona, Kansas and Oregon 1913 territory of Alaska grants suffrage 1914 Montana and Nevada grant voting rights to women, 1915 Women of Denmark are enfranchised. 1917 Women win the right to vote in North Dakota, Ohio, Indiana, Rhode Island, Nebraska, Michigan, New York, and Arkansas 1918 Women of Austria, Canada, Czechoslovakia, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Poland, Scotland, and Wales are enfranchised. 1919 Women of Azerbaijan Republic, Belgium, British East Africa, Holland, Iceland, Luxembourg, Rhodesia, and Sweden are enfranchised. Suffrage Amendment is passed by the US Senate on June 4th and the battle for ratification by at least 36 states begins. 1920 In February the LEAGUE OF WOMEN VOTERS was formed by Carrie Chapman Catt at the close of the National American Women Suffrage Alliance last Convention. The League of Women Voters is to this day one of the country's preeminent nonpartisan voter education groups.