Khayelitsha, Mitchells Plain, Greater Blue Downs District Draft Baseline and Analysis Report 2019 State of the Built Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

36261 22-3 Road Carrier Permits

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA March Vol. 573 Pretoria, 22 2013 Maart No. 36261 N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 301221—A 36261—1 2 No. 36261 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 22 MARCH 2013 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the senderʼs respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. CONTENTS INHOUD Page Gazette Bladsy Koerant No. No. No. No. No. No. Transport, Department of Vervoer, Departement van Cross Border Road Transport Agency: Oorgrenspadvervoeragentskap aansoek- Applications for permits:.......................... permitte: .................................................. Menlyn..................................................... 3 36261 Menlyn..................................................... 3 36261 Applications concerning Operating Aansoeke aangaande -

38678 10-4 Roadcarrierp Layout 1

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA Vol. 598 Pretoria, 10 April 2015 No. 38678 N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 501272—A 38678—1 2 No. 38678 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 10 APRIL 2015 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the sender’s respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. CONTENTS INHOUD Page Gazette Bladsy Koerant No. No. No. No. No. No. Transport, Department of Vervoer, Departement van Cross Border Road Transport Agency: Oorgrenspadvervoeragentskap aansoek- Applications for permits:.......................... permitte: .................................................. Menlyn..................................................... 3 38678 Menlyn..................................................... 3 38678 Applications concerning Operating Aansoeke aangaande Bedryfslisensies:. -

Economy, Society and Municipal Services in Khayelitsha

Economy, society and municipal services in Khayelitsha Jeremy Seekings Centre for Social Science Research, University of Cape Town Report for the Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of Police Inefficiency in Khayelitsha and a Breakdown in Relations between the Community and the Police in Khayelitsha December 2013 Summary Established in 1983, Khayelitsha has grown into a set of neighbourhoods with a population of about 400,000 people, approximately one half of whom live in formal houses and one half in shacks, mostly in informal settlements rather than backyards. Most adult residents of Khayelitsha were born in the Eastern Cape, and retain close links to rural areas. Most resident children were born in Cape Town. Immigration rates seem to have slowed. The housing stock – formal and informal – has grown faster than the population, resulting in declining household size, as in South Africa as a whole. A large minority of households are headed by women. The state has an extensive reach across much of Khayelitsha. Access to public services – including water, electricity and sanitation – has expanded steadily, but a significant minority of residents continue to rely on communal, generally unsatisfactory facilities. Children attend schools, and large numbers of residents receive social grants (especially child support grants). Poverty is widespread in Khayelitsha: Half of the population of Khayelitsha falls into the poorest income quintile for Cape Town as a whole, with most of the rest falling into the second poorest income quintile for the city. The median annual household income in 2011, according to Census data, was only about R20,000 (or R6,000 per capita). -

PENINSULA MAP Visitor Information Centres Police Station WITSAND

MAMRE PELLA ATLANTIS Cape Town Tourism PENINSULA MAP Visitor Information Centres Police Station WITSAND R27 Transport Information Centre 0800 656 463 CAPE TOWN TOURISM SERVICES GENERAL TRAVEL INFORMATION: Champagne All you need to know about Cape Town P hila W d el Adam Tas e ph and travelling within the City. s i t a C Wellington o R302 a PHILADELPHIA s R304 t k KOEBERG M c RESERVATIONS: e You can do all your bookings via Cape Town Tourism a e l b m e i e R s Visitor Information Centres, online and via our Call Centre. b u an r V y n y a r J u Silwerstroom b SANPARKS BOOKINGS/SERVICES: s R304 Reservations, Activity Cards, Green e Main Beach lm a Cards & Permits at designated Visitor Information Centres. M ld DUYNEFONTEIN O R45 COMPUTICKET BOOKINGS: Book your Theatre, Events or Music Shows R312 at designated Visitor Information Centres. M19 Melkbosstrand N7 MELKBOSSTRAND R44 WEBTICKETS ONLINE BOOKINGS: Langenh Robben Island Trips, Kirstenbosch oven Concerts, Table Mountain Cable Car Trip at all Cape Town Tourism R304 PAARL M14 Visitor Information Centres. Suid Agter Paarl R302 R27 M58 CITY SIGHTSEEING HOP ON HOP OFF BUS TICKETS: Purchase your tickets Main West Coast at designated Visitor Information Centres. Otto Du Plessis l BLAAUWBERG e Lichtenberg w u e h p li Visse Adderley MYCITI BUS ROUTE SERVICE: Purchase and load your MyConnect Card rshok K N1 Big Bay BLOUBERGSTRAND at Cape Town International Airport and City Centre. Big Bay i le v West Coast M48 s on Marine m PARKLANDS Si m ROBBEN ISLAND a Wellington d ts o R302 KLAPMUTS TABLE -

AC097 FA Cape Town City Map.Indd

MAMRE 0 1 2 3 4 5 10 km PELLA ATLANTIS WITSAND R27 PHILADELPHIA R302 R304 KOEBERG R304 I CAME FOR DUYNEFONTEIN MAP R45 BEAUTIFULR312 M19 N7 MELKBOSSTRAND R44 LANDSCAPES,PAARL M14 R304 R302 R27 M58 AND I FOUND Blaauwberg BEAUTIFULN1 PEOPLE Big Bay BLOUBERGSTRAND M48 B6 ROBBEN ISLAND PARKLANDS R302 KLAPMUTS TABLE VIEW M13 JOOSTENBERG KILLARNEY DURBANVILLE VLAKTE City Centre GARDENS KRAAIFONTEIN N1 R44 Atlantic Seaboard Northern Suburbs SONSTRAAL M5 N7 Table Bay Sunset Beach R304 Peninsula R27 BOTHASIG KENRIDGE R101 M14 PLATTEKLOOF M15 Southern Suburbs M25 EDGEMEAD TYGER VALLEY MILNERTON SCOTTSDENE M16 M23 Cape Flats M8 BRACKENFELL Milnerton Lagoon N1 Mouille Point Granger Bay M5 Helderberg GREEN POINT ACACIA M25 BELLVILLE B6 WATERFRONT PARK GOODWOOD R304 Three Anchor Bay N1 R102 CAPE TOWN M7 PAROW M23 Northern Suburbs STADIUM PAARDEN KAYAMANDI SEA POINT EILAND R102 M12 MAITLAND RAVENSMEAD Blaauwberg Bantry Bay SALT RIVER M16 M16 ELSIESRIVIER CLIFTON OBSERVATORY M17 EPPING M10 City Centre KUILS RIVER STELLENBOSCH Clifton Bay LANGA INDUSTRIA M52 Cape Town Tourism RHODES R102 CAMPS BAY MEMORIAL BONTEHEUWEL MODDERDAM Visitor Information Centres MOWBRAY N2 R300 M62 B6 CABLE WAY ATHLONE BISHOP LAVIS M12 M12 M3 STADIUM CAPE TOWN TABLE MOUNTAIN M5 M22 INTERNATIONAL Police Station TABLE RONDEBOSCH ATHLONE AIRPORT BAKOVEN MOUNTAIN NATIONAL BELGRAVIA Koeël Bay PARK B6 NEWLANDS RYLANDS Hospital M4 CLAREMONT GUGULETU DELFT KIRSTENBOSCH M54 R310 Atlantic Seaboard BLUE DOWNS JAMESTOWN B6 Cape Town’s Big 6 M24 HANOVER NYANGA Oude Kraal KENILWORTH PARK -

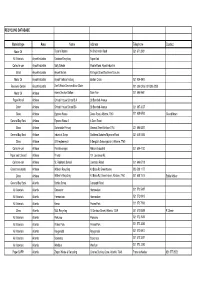

Name Corporate/Franchise Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Suburb

Name Corporate/Franchise Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Suburb Greater Area/City Province Main Phone GAUTENG Domino's Pizza Alberton Corporate 1 Venter St Shop 7, Jacqueline Mall Alberton Johannesburg Gauteng 011 908 3180 Domino's Pizza Bellairs Corporate Cnr Malibongwe & Bellairs Dr Shop 34, Bel Air Shopping Mall North Riding Johannesburg Gauteng 011 704 0907 Domino's Pizza Benoni Rynfield Corporate 178 Pretoria Rd Shop 2, Rynfield Shopping Centre Rynfield Benoni Gauteng 011 425 2101 Domino's Pizza Boksburg Corporate Cnr Rietfontein Rd & Rigg St Shop 2, The Square Shopping Centre Jansen Park Boksburg Gauteng 011 826 7013 Domino's Pizza Bonaero Park Franchise Cnr Tempelhof South St & Louis Botha Rd Shop 28, Aero Shopping Centre Bonaero Park Kempton Park Gauteng 011 973 1020 Domino's Pizza Brakpan Corporate 757 Voortrekker Rd Video Town, Brakpan Building Brakpan East Rand Gauteng 011 744 4723 Domino's Pizza Bram Fischer Blairgowrie Corporate 117 Bram Fischer Dr Shop 1, Canterbury Crossing Shopping Centre Blairgowrie Randburg Gauteng 011 326 1111 Domino's Pizza Bryan Park Corporate Cnr Grosvenor Rd & Cumberland Ave Shop 19A, Bryan Park Shopping Centre Bryanston Johannesburg Gauteng 011 463 2528 Domiono's Pizza Cherry Lane Corporate Cnr Fehrsen & Middel St Erf 437, Nieuw Muckleneuk Brooklyn Pretoria Gauteng 012 346 3599 Domino's Pizza Comaro Crossing Corporate Cnr Oak Stt Boundary Rd Shop FF21B Oakdene Gauteng 011 759 7269 Domino's Pizza Faerie Glen Corporate Cnr Solomon Mahlangu Dr & Haymeadow Cres Shop 4, Dischem Centre Faerie Glen Pretoria -

From Crossroads to Khayelitsha to . . .?

house community youth programmes, the Black Sash their memoirs — what is significant is that the people be Advice Office and a clinic have been damaged or destroyed. lieve certain things to be true and act accordingly. Perhaps The more optimistic see a settling of private scores at the the most depressing aspect of the beliefs is the despair and root of at least a part of the destruction, and argue that the paralysis that they engender. The police are seen as some of the trouble over the festive season can be attri the agents of the oppressive power and hence are unavail buted to migrants coming home for their annual holidays able as a source of protection or help, while the shadowy and the demon drink. local groups, be they criminal gangs or agents of the known Much of the preceding paragraph is speculation — a sum organisations, cannot be resisted, no matter what sacrifices mary of the beliefs of people in and near the black com they demand of the workers or pupils in the townships. munity. Whether the broad outlines or the details are true And the good people can do nothing.D may never be known until some crucial survivors record by DOT CLEMINSHAW FROM CROSSROADS TO KHAYELITSHA TO . .? White settlement at the Cape has always relied on an units from the mid-60's for a period of 10 years while the industrious black labour force. By 1900 some 10 000 black population increased by over 60% blacks resided in Cape Town, some renting, others owning Pressures of rural poverty brought many workseekers their homes. -

Serious Crime in Khayelitsha and Surrounding Areas

SERIOUS CRIME IN KHAYELITSHA AND SURROUNDING AREAS CRIME RESEARCH AND STATISTICS CRIME INTELLIGENCE Compiled by M EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This assessment of Khayelitsha and its surrounding areas is based purely on the recorded incidence of crime and was done without any recent contact with and/or visit to any of the stations under consideration (the current situation with regard to the position of the CIO/CIAC at stations is explained in the introduction). Although this methodology possibly promoted increased objectivity in the crime assessment, it may suffer from a lack of insight regarding the crime situation at ground level in Khayelitsha, Mitchells Plain, Harare, Lingelethu West and Mfuleni and thus not present a full explanation. It should again be emphasized that it is an assessment of crime and not of policing in Khayelitsha. The reader should be aware of the fact that Khayelitsha and Mitchells Plain were declared presidential stations in the Western Cape during the late nineties of the previous centuryi. The strategy behind declaring 14 police stations in the Republic of South Africa as presidential stations was that these stations were generally identified as the largest single generators of crime in their respective provinces. The high levels of particularly violent crime in these precincts were also due to an extremely complex web of historical, social, economic and environmental issues which couid only be addressed by a massive, fully integrated effort involving both Government (not only the SAPS) and the community, if the present Khayelitsha precinct as in (2012) and part of its environment (Harare and Lingelethu West) which formerly formed part of the historical Khayelitsha precinct of 1999 are compared to the situation that existed in 1999, the question needs to be asked and answers found regarding the nature and extent of changes over the past 13 years - and whether a massive, fully — integrated government-community effort did in fact materialized in the areas. -

The Making and Re-Imagining of Khayelitsha

The Making and Re-imagining of Khayelitsha Josette Cole Executive Director, Development Action Group (DAG) and Research Associate, Centre for Archive and Public Culture, University of Cape Town Report for the Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of Police Inefficiency in Khayelitsha and a Breakdown in Relations between the Community and the Police in Khayelitsha January 2013 PREFACE During a working career that now spans 37 years I have worked in a number of institutions – i.e. VERITAS, the Surplus People’s Project, W. Cape (SPP), the MANDLOVU Development Initiative and, the Development Action Group (DAG). In all of these I have both honed and applied incremental skills learnt from direct practice to design and implement programmes and projects related to urban land, housing, local government, community development and, capacity building in the context of a pro-poor agenda. Between 1996 and 2012 I also worked as a freelance development consultant and researcher through my small company, Social Trends Development Services, where I worked on numerous assignments for government, the NGO sector, and international NGOs related to the design and evaluation of a range of programmes and projects linked to reconstruction and development in the context of our democratic transition. In between my professional work I have researched, written and published numerous articles, academic papers and books, three of the latter extensively cover various aspects of Cape Town’s social history, with a special focus on past and present settlement life in the South-east Metro of the city. I am a Research Associate in the Archive and Public Culture Research Initiative based in the Social Anthropology Department at the University of Cape Town (UCT) and about to formally register as a PhD candidate in Historical Studies at UCT. -

39542 24-12 Roadcarrier

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID AFRIKA Regulation Gazette No. 10177 Regulasiekoerant December Vol. 606 24 2015 No. 39542 Desember ISSN 1682-5843 N.B. The Government Printing Works will 39542 not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes 9 771682 584003 AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 2 No. 39542 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 24 DECEMBER 2015 1 A message from Government Printing Oit)TV6, Works Notice Submissions Rule: Single notice, single email Dear Valued Customer, Over the last six months, GPW has been experiencing problems with many customers that are still not complying with GPW’s rule of single notice, single email (with proof of payment or purchase order). You are advise that effective from 18 January 2016, all notice submissions received that do no comply with this rule will be failed by our system and your notice will not be processed. In the case where a Z95, Z95Prov or TForm3 Adobe form is submitted with content, there should be a separate Adobe form completed for each notice content which must adhere to the single notice, single email rule. A reminder that documents must be attached separately in your email to GPW. (In other words, your email should have an electronic Adobe Form plus proof of payment/purchase order – 2 separate attachments – where notice content is applicable, it should also be a 3rd separate attachment). To those customers who are complying with this rule, we say Thank you! Regards, Government Printing Works This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za STAATSKOERANT, 24 DESEMBER 2015 No. -

The Youth Book. a Directory of South African Youth Organisations, Service Providers and Resource Material

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 432 485 SO 029 682 AUTHOR Barnard, David, Ed. TITLE The Youth Book. A Directory of South African Youth Organisations, Service Providers and Resource Material. INSTITUTION Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria (South Africa). ISBN ISBN-0-7969-1824-4 PUB DATE 1997-04-00 NOTE 455p. AVAILABLE FROM Programme for Development Research, Human Sciences Research Council, P 0 Box 32410, 2017 Braamfontein, South Africa; Tel: 011-482-6150; Fax: 011-482-4739. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC19 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Developing Nations; Educational Resources; Foreign Countries; Schools; Service Learning; *Youth; *Youth Agencies; *Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS Service Providers; *South Africa; Youth Service ABSTRACT With the goal of enhancing cooperation and interaction among youth, youth organizations, and other service providers to the youth sector, this directory aims to give youth, as well as people and organizations involved and interested in youth-related issues, a comprehensive source of information on South African youth organizations and related relevant issues. The directory is divided into three main parts. The first part, which is the background, is introductory comments by President Nelson Mandela and other officials. The second part consists of three directory sections, namely South African youth and children's organizations, South African educational institutions, including technical training colleges, technikons and universities, and South African and international youth organizations. The section on South African youth and children's organizations, the largest section, consists of 44 sectoral chapters, with each organization listed in a sectoral chapter representing its primary activity focus. Each organization is at the same time also cross-referenced with other relevant sectoral chapters, indicated by keywords at the bottom of an entry. -

Material Type Area Name Address Telephone Contact RECYCLING DATABASE

RECYCLING DATABASE Material type Area Name Address Telephone Contact Motor Oil - Taylor's Motors 14 Chichester Road 021 671 2931 All Materials Airport Industria Rainbow Recycling Airport Ind Collect-a-can Airport Industria Solly Sebola Mobile Road, Airpot industria Metal Airport Industria Airport Metals Michigan Street/'Northern Suburbs Motor Oil Airport Industria Airport Vehicle Testing Boston Circle 021 934 4900 Recovery Centre Airport Industria Don't Waste Services Brian Slater 021 386 0206 / 021 386 0208 Motor Oil Athlone Adens Service Station Eden Ave 021 696 9941 Paper-Mondi Athlone Christel House School S A 38 Bamford Avenue Other Athlone Christel House School SA 38 Bamford Avenue 021 697 3037 Glass Athlone Express Waste Desre Road, Athlone, 7760 021 638 6593 Gerard Moen General Buy Back Athlone Express Waste 2 5 Desri Road Glass Athlone Garlandale Primary General Street Athlone 7764 021 696 8327 General Buy Back Athlone Industrial Scrap Southern Suburbs/'Mymona Road 021 448 5395 Glass Athlone LR Heydenreych 5 Bergzich Schoongezicht, Athlone, 7760 Collect-a-can Athlone Pen Beverages Athlone Industrial 021 684 4130 Paper and C/board Athlone Private 151 Lawrence Rd, Collect-a-can Athlone St. Raphaels School Lawrence Road 021 696 6718 Glass/ tins/ plastic Athlone Walkers Recycling 43 Brian Rd Greenhaven 083 508 1177 Glass Athlone Walker's Recycling 43 Brian Rd, Greenhaven, Athlone, 7760 021 638 1515 Eddie Walker General Buy Back Atlantis Berties Scrap Conaught Road All Materials Atlantis Grosvenor Hermeslaan 021 572 5487 All Materials