Spatial Interactions in Forest Clearing: Deforestation and Fragmentation in Costa Rica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mecanismo Socio Ambiental Diquis

MECANISMO SOCIO AMBIENTAL DIQUIS (MESADI) EN EL MARCO DEL COMPONENTE DE MECANISMOS DE COMPENSACIÓN PARA CENTROAMÉRICA Y REPÚBLICA DOMINICANA Preparado por: Sud-Austral Consulting Para: Programa Reducción de Emisiones de la Deforestación y Degradación de Bosques en Centroamérica y República Dominicana (REDD – CCAD/GIZ) Enero de 2015 Esta publicación expone los principales elementos de base y el diseño inicial propuesto para la implementación de un Mecanismo Socio Ambiental en Costa Rica, en el marco de las actividades del Programa Regional de Reducción de Emisiones de la Degradación y Deforestación de Bosques en Centroamérica y República Dominicana (REDD/CCAD-GIZ). Componente II de Mecanismos de Compensación del Programa. Publicado por Programa Regional REDD/CCAD-GIZ Oficina Registrada Apartado Postal 755 Bulevar, Orden de Malta, Edificio GIZ, Urbanización Santa Elena, Antiguo Cuscatlán, La Libertad. El Salvador, C.A. E [email protected] I www.reddccadgiz.org Responsable Carlos Roberto Pérez, Especialista Sectorial. Programa REDD/CCAD-GIZ [email protected] Autores Patricio Emanuelli Avilés - Consultor. Programa REDD/CCAD-GIZ [Sud-Austral Consulting SpA] Juan Andrés Torrealba Munizaga - Consultor. Programa REDD/CCAD-GIZ [Sud-Austral Consulting SpA] Fabián Milla Araneda - Consultor. Programa REDD/CCAD-GIZ [Sud-Austral Consulting SpA] Carlos Roberto Pérez, Especialista Sectorial. Programa REDD/CCAD-GIZ Sonia Lobo – SINAC Gil Ruiz - SINAC Patricia Ruiz – Biomarcc Enlace Equipo Técnico Regional de Mecanismos de Compensación Sonia Lobo – SINAC Diseño Gráfico Alfonso Quiroz H. - Consultor. Programa REDD/CCAD-GIZ [Sud-Austral Consulting SpA] Diciembre 2014 Componente: Mecanismos de Compensación Área Temática: Mecanismos Nacionales de Compensación País: Costa Rica MECANISMO SOCIOAMBIENTAL DEL DIQUÍS – COSTA RICA 2 I. -

Gobierno Anuncia Cambio De Alertas Y Fortalecimiento De Trabajo Con Comunidades

4 de agosto 2020 GOBIERNO ANUNCIA CAMBIO DE ALERTAS Y FORTALECIMIENTO DE TRABAJO CON COMUNIDADES • 3 cantones bajaron de alerta naranja amarilla, así como dos distritos de Desamparados y uno de Alajuela. • 39 distritos nuevos se suman a la lista de lugares con alerta temprana por virus respiratorios. • Gobierno intensifica estrategia con comunidades en mayor riesgo Tras una valoración epidemiológica por parte del Ministerio de Salud, realizadas en las semanas 30 y 31, la Comisión Nacional de Prevención de Riesgos y Atención de Emergencias (CNE), hace un reajuste en la condición de alerta Naranja a Alerta Amarilla para el cantón de Mora y los distritos de San Cristóbal y Frailes de Desamparados en la provincia de San José. Asimismo, baja a alerta amarilla el distrito de Sarapiquí y el cantón de Poás en Alajuela, así como el cantón de San Rafael de Heredia. La información fue dada a conocer en conferencia de prensa por el jefe de operaciones de la CNE, Sigifredo Pérez Fernández, quien manifestó que “las modificaciones evidencian el acatamiento y la responsabilidad individual que hemos tenido como sociedad para disminuir la curva de contagio en las comunidades”. Por una actualización en las alertas sindrómicas, 39 distritos nuevos se suman a la lista de lugares con alerta temprana por virus respiratorios anunciada el pasado 30 de julio. Actualmente, son 71 distritos que se encuentran en alerta amarilla pero mantienen el riesgo debido a un incremento en las consultas por tos y fiebre, lo cual aumenta el riesgo de enfrentar una alerta naranja próximamente, dado que son síntomas asociados al COVID-19. -

División Territorial Electoral Que Regirá Para Las Elecciones Del 6 De Febrero De 2022

DIVISIÓN TERRITORIAL ELECTORAL QUE REGIRÁ PARA LAS ELECCIONES DEL 6 DE FEBRERO DE 2022 DECRETO n.º 2-2021 Aprobado en sesión ordinaria del TSE n.º42-2021 de 20 de mayo de 2021 Publicado en el Alcance n.°114 a La Gaceta n.º107 de 04 de junio de 2021 ____________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ Decreto 2-2021: División territorial electoral que regirá para las elecciones del 6 de febrero de 2022 1 N.° 2-2021 EL TRIBUNAL SUPREMO DE ELECCIONES De conformidad con los artículos 99 de la Constitución Política, 12 incisos a) y k) y 143 del Código Electoral, el Decreto n.° 07-2020, publicado en el Alcance n.° 2 a La Gaceta n.º 4 del 7 de enero de 2021 y el Decreto Ejecutivo n.º 42838-MGP, publicado en La Gaceta n.° 25, Alcance Digital n.° 26 del 5 de febrero de 2021. DECRETA La siguiente DIVISION TERRITORIAL ELECTORAL Artículo 1.- La División Territorial Electoral que regirá para las elecciones del 6 de febrero del 2022 en los siguientes términos: 1 SAN JOSE 01 CANTON SAN JOSE Mapa I DISTRITO CARMEN 069 Hs 011 CARMEN*/. POBLADOS: AMON*, ATLANTICO, CUESTA DE MORAS (PARTE NORTE), CUESTA DE NUÑEZ, FABRICA DE LICORES, LAIZA, MORAZAN*, OTOYA. 069 Ht 015 ARANJUEZ*D. POBLADOS: CALIFORNIA (PARTE NORTE)*, CALLE LOS NEGRITOS (PARTE OESTE), EMPALME, ESCALANTE*, JARDIN, LOMAS ESCALANTE, LUZ, ROBERT, SANTA TERESITA/, SEGURO SOCIAL/. II DISTRITO MERCED 069 Hr 012 BARRIO MEXICO*D/. POBLADOS: BAJOS DE LA UNION, CASTRO, CLARET*, COCA COLA, FEOLI, IGLESIAS FLORES, JUAN RAFAEL MORA*, JUAREZ, NUEVO MEXICO, PARQUE, PASEO COLON (PARTE NORESTE), PASO DE LA VACA, URB. -

Essays on the Evaluation of Land Use Policy: the Effects of Regulatory Protection on Land Use and Social Welfare

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Public Management and Policy Dissertations 10-24-2007 Essays on the Evaluation of Land Use Policy: The Effects of Regulatory Protection on Land Use and Social Welfare Kwaw Senyi Andam Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/pmap_diss Part of the Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Recommended Citation Andam, Kwaw Senyi, "Essays on the Evaluation of Land Use Policy: The Effects of Regulatory Protection on Land Use and Social Welfare." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/pmap_diss/20 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Management and Policy Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ESSAYS ON THE EVALUATION OF LAND USE POLICY: THE EFFECTS OF REGULATORY PROTECTION ON LAND USE AND SOCIAL WELFARE A Dissertation Presented to The Academic Faculty By Kwaw Senyi Andam In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Public Policy Georgia State University and Georgia Institute of Technology May 2008 ESSAYS ON THE EVALUATION OF LAND USE POLICY: THE EFFECTS OF REGULATORY PROTECTION ON LAND USE AND SOCIAL WELFARE Approved by: Dr. Paul J. Ferraro, Advisor Dr. Douglas S. Noonan Andrew Young School of Policy Studies School of Public Policy Georgia State University Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Gregory B. Lewis Dr. Alexander S. P. Pfaff Andrew Young School of Policy Studies Terry Sanford Institute Georgia State University Duke University Dr. -

Nombre Del Comercio Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario

Nombre del Provincia Distrito Dirección Horario comercio Almacén Agrícola Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Cruce Del L-S 7:00am a 6:00 pm Aguas Claras Higuerón Camino A Rio Negro Comercial El Globo Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, contiguo L - S de 8:00 a.m. a 8:00 al Banco Nacional p.m. Librería Fox Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, frente al L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Liceo Aguas Claras p.m. Librería Valverde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 500 norte L-D de 7:00 am-8:30 pm de la Escuela Porfirio Ruiz Navarro Minisúper Asecabri Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Las Brisas L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 6:00 400mts este del templo católico p.m. Minisúper Los Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, Cuatro L-D de 6 am-8 pm Amigos Bocas diagonal a la Escuela Puro Verde Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala Aguas Claras, Porvenir L - D de 7:00 a.m. a 8:00 Supermercado 100mts sur del liceo rural El Porvenir p.m. (Upala) Súper Coco Alajuela Aguas Claras Alajuela, Upala, Aguas Claras, 300 mts L - S de 7:00 a.m. a 7:00 norte del Bar Atlántico p.m. MINISUPER RIO Alajuela AGUAS ALAJUELA, UPALA , AGUAS CLARAS, L-S DE 7:00AM A 5:00 PM NIÑO CLARAS CUATRO BOCAS 200M ESTE EL LICEO Abastecedor El Alajuela Aguas Zarcas Alajuela, Aguas Zarcas, 25mts norte del L - D de 8:00 a.m. -

Plan De Desarrollo Rural Del Territorio Buenos Aires-Coto Brus 2015-2020

PLAN DE DESARROLLO RURAL DEL TERRITORIO BUENOS AIRES-COTO BRUS 2015-2020 1 PRESENTACION Y AGRADECIMIENTO El 25 de setiembre de 2014, para el Territorio Buenos Aires-Coto Brus se registra como una fecha histórica por haberse logrado la conformación del primer Comité Directivo del Consejo Territorial de Desarrollo Rural (CTDR), elegido mediante Asamblea General, promovida por el Instituto de Desarrollo Rural (Inder). Al amparo de la Ley 9036 y del Reglamento de Constitución y Funcionamiento de los Consejos Territoriales y Regionales de Desarrollo Rural, la Oficina Territorial del Inder con sede en San Vito de Coto Brus, apoyada por la Dirección Regional, la Oficina de San Isidro y personal de Oficinas Centrales, inició el proceso de divulgación de la nueva Ley 9036, promoviendo visitas a las comunidades en cada uno de los distritos de los cantones de Buenos Aires y Coto Brus. Simultáneamente, en esta visitas y aprovechando la participación de los distintos actores del Territorio, se procedió con el abordaje enfocado a la motivación, sensibilización e inducción de los pobladores con relación al procedimiento metodológico para la constitución y funcionamiento del Consejo Territorial de Desarrollo Rural, como una instancia innovadora, capaz de impulsar la gestión y la negociación planificada, que le permita a las familias el acceso a bienes y servicios para mejorar las condiciones sociales y económicas y que les facilite el arraigo con mejor calidad de vida en el plano individual y colectivo. Esta nueva forma de construir de manera integral -

Instituto De Desarrollo Rural

Instituto de Desarrollo Rural Dirección Región Brunca Oficina Subregional Osa Caracterización del Territorio Península de Osa Elaborado por: Oficina Subregional Osa y Shirley Amador Muñoz Año 2016 1 TABLA DE CONTENIDOS INDICE DE CUADROS ........................................................................................ 4 INDICE DE GRÁFICOS ....................................................................................... 5 INDICE DE FIGURAS .......................................................................................... 6 1. ORDENAMIENTO TERRITORIAL Y TENENCIA DE LA TIERRA .................. 7 1.1. Mapa del Territorio Península de Osa ................................................... 7 1.2. Antecedentes y evolución histórica del Territorio .................................. 7 1.3. Ubicación y límites del Territorio.......................................................... 16 1.4. Hidrografía del Territorio ...................................................................... 17 1.5. Información del cantón y distritos que forman parte del Territorio ....... 18 1.6. Uso actual de la tierra del Territorio ..................................................... 18 1.7. Asentamientos establecidos en el Territorio ........................................ 19 2. DESARROLLO HUMANO ............................................................................. 28 2.1. Población actual .................................................................................. 28 2.2. Distribución territorial de la población en urbano y -

Institucion Codigo Presupuestario Clase De Puesto Especialidad Direccion Regional Circuito Puesto Provi

MINISTERIO DE EDUCACION PUBLICA DIRECCION DE RECURSOS HUMANOS DEPARTAMENTO DE ASIGNACION DEL RECURSO HUMANO UNIDAD ADMINISTRATIVA PUESTOS VACANTES PARA COMPROMETER EN PROPIEDAD; ART 15 CODIGO DIRECCION N° PEDIMENTO UBICACION/ INSTITUCION PRESUPUESTARIO CLASE DE PUESTO ESPECIALIDAD REGIONAL CIRCUITO PUESTO PROVINCIA CANTON DISTRITO NOCTURNO SERVIDOR INTERINO IDENTIFICACION ESTRATO OBSERVACION MEP-00233-2016 PARRITA 57301-68-3755 COCINERO SIN ESPECIALIDAD AGUIRRE 03 440108 PUNTARENAS PARRITA PARRITA N/A RAMIREZ SILVA ANA 601390684 CALIFICADO MEP-00195-2016 MARIA LUISA DE CASTRO 57301-68-3772 COCINERO SIN ESPECIALIDAD AGUIRRE 01 440220 PUNTARENAS AGUIRRE QUEPOS N/A ROJAS VILLARREAL MELISSA 603270328 CALIFICADO MEP-00161-2017 FINCA LLORONA 57301-68-3774 COCINERO SIN ESPECIALIDAD AGUIRRE 02 440239 PUNTARENAS AGUIRRE QUEPOS N/A CESPEDES PEREZ LIDIA 602110454 CALIFICADO DIRECCION REGIONAL MEP-00117-2014 EDUCACION 55700-44-223 MISCELANEO DE SERVICIO CIVIL 1 SERVICIOS BASICOS AGUIRRE DRE 402826 PUNTARENAS AGUIRRE QUEPOS N/A CERDAS MACHADO GUISELLE 602810609 OPERATIVO DIRECCION REGIONAL MEP-00808-2014 EDUCACION 55700-44-223 OFICIAL DE SEGURIDAD DE SERVICIO CIVIL 1 SIN ESPECIALIDAD AGUIRRE DRE 402829 PUNTARENAS AGUIRRE QUEPOS N/A ZELEDON PRADO MARCO 900900846 OPERATIVO MEP-00401-2015 LA INMACULADA 57301-68-3700 OFICIAL DE SEGURIDAD DE SERVICIO CIVIL 1 SIN ESPECIALIDAD AGUIRRE 01 439723 PUNTARENAS AGUIRRE QUEPOS N/A ERIC MAURICIO VENEGAS GRIJALBA 602650525 OPERATIVO MEP-00756-2014 LAS BRISAS 57301-68-3719 OFICIAL DE SEGURIDAD DE SERVICIO CIVIL 1 -

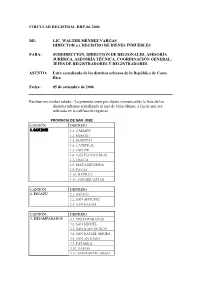

Circular Registral Drp-06-2006

CIRCULAR REGISTRAL DRP-06-2006 DE: LIC. WALTER MÉNDEZ VARGAS DIRECTOR a.i. REGISTRO DE BIENES INMUEBLES PARA: SUBDIRECCIÓN, DIRECCIÓN DE REGIONALES, ASESORÍA JURÍDICA, ASEOSRÍA TÉCNICA, COORDINACIÓN GENERAL, JEFES DE REGISTRADORES Y REGISTRADORES. ASUNTO: Lista actualizada de los distritos urbanos de la República de Costa Rica Fecha: 05 de setiembre de 2006 Reciban mi cordial saludo. La presente tiene por objeto comunicarles la lista de los distritos urbanos actualizada al mes de Julio último, a fin de que sea utilizada en la califiación registral. PROVINCIA DE SAN JOSE CANTÓN DISTRITO 1. SAN JOSE 1.1. CARMEN 1.2. MERCED 1.3. HOSPITAL 1.4. CATEDRAL 1.5. ZAPOTE 1.6. SAN FCO DOS RIOS 1.7. URUCA 1.8. MATA REDONDA 1.9. PAVAS 1.10. HATILLO 1.11. SAN SEBASTIAN CANTÓN DISTRITO 2. ESCAZU 2.1. ESCAZU 2.2. SAN ANTONIO 2.3. SAN RAFAEL CANTÓN DISTRITO 3. DESAMPARADOS 3.1. DESAMPARADOS 3.2. SAN MIGUEL 3.3. SAN JUAN DE DIOS 3.4. SAN RAFAEL ARRIBA 3.5. SAN ANTONIO 3.7. PATARRA 3.10. DAMAS 3.11. SAN RAFAEL ABAJO 3.12. GRAVILIAS CANTÓN DISTRITO 4. PURISCAL 4.1. SANTIAGO CANTÓN DISTRITO 5. TARRAZU 5.1. SAN MARCOS CANTÓN DISTRITO 6. ASERRI 6.1. ASERRI 6.2. TARBACA (PRAGA) 6.3. VUELTA JORCO 6.4. SAN GABRIEL 6.5.LEGUA 6.6. MONTERREY CANTÓN DISTRITO 7. MORA 7.1 COLON CANTÓN DISTRITO 8. GOICOECHEA 8.1.GUADALUPE 8.2. SAN FRANCISCO 8.3. CALLE BLANCOS 8.4. MATA PLATANO 8.5. IPIS 8.6. RANCHO REDONDO CANTÓN DISTRITO 9. -

Inec Requiere 2.200 Personas Para Realizar Censo Nacional Agropecuario

INEC REQUIERE 2.200 PERSONAS PARA REALIZAR CENSO NACIONAL AGROPECUARIO Personal se contratará por un mes para censar las fincas del país. El Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos, INEC, se encuentra en este momento reclutando a 2.200 personas para que trabajen como personal supervisor y entrevistador en el VI Censo Nacional Agropecuario a desarrollarse del 2 al 30 de junio próximo. El INEC considera importante que las personas que participen tengan alguna experiencia en el sector agrícola o ganadero y que conozcan la zona donde viven pues es donde podrían trabajar. El INEC hace un llamado especial a aquellas personas que cuenten con un título preferiblemente de un Colegio Técnico Agropecuario o bien estudiantes o egresados de carreras afines a la agricultura y ganadería, para que se incorporen al equipo de trabajo de campo CENAGRO. Para la contratación de este personal se pide de forma opcional contar con teléfono inteligente y algún medio de transporte. Los requerimientos se pueden flexibilizar de acuerdo a las regiones geográficas donde hay menor disponibilidad de personal. Hasta la fecha el INEC ha recibido una cantidad importante de inscripciones, sin embargo hay zonas donde se percibe un faltante (recuadro) y se hace un llamado a la población de los siguientes lugares para que se inscriba y llene esas vacantes. LUGARES DONDE PRINCIPALMENTE SE REQUIERE PERSONAL REGION CANTON DISTRITO Pacífico central San Mateo Desmonte, Labrador Aguirre Naranjillo Puntarenas Manzanillo, Arancibia Chorotega Abangares Sierra Cañas Bebedero Hojancha -

Handbook of South American Indians

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION BUREAU OF AMERICAN ETHNOLOGY BULLETIN 143 HANDBOOK OF SOUTH AMERICAN INDIANS Julian H. Steward, Editor Volume 4 THE CIRCUM-CARIBBEAN TRIBES Prepared in Cooperation With the United States Department of State as a Project of the Interdepartmental Committee for Scientific and Cultural Cooperation ^s^^mm^w^ UNITED STATES GOVERNMEINT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1948 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington 25, D. C. Part 1. Central American Cultures CENTRAL AMERICAN CULTURES: AN INTRODUCTION^ By Frederick Johnson Central America may be defined culturally as the region extending from the Atrato and San Juan River Valleys in Colombia nearly to the western boundary of Honduras (map 1). It has a fundamental unity in what may be a basic cultural tradition or cultural substructure. This basic culture has a distinctly South American cast, and the region marks the northern limit of culture complexes which were probably derived from South Amer- ica. The region has, however, been exposed to influences from the north- ern, that is, the Meso-American cultures. The continuing stream of cultural diffusion from both the north and south has produced a strong overlay of foreign elements which gives many local cultures a superficial similarity to those of neighboring regions. These tend to obscure the basic cultures. GEOGRAPHY The culture area of Central America is not coterminous with a geo- graphical province.^ Central America includes several portions of a larger geographic region which extends north to the "Great Scarp" of Oaxaca, Mexico, and south to the northern terminus of the Andes, the eastern slopes of the Atrato River Valley. -

The Lure of Costa Rica's Central Pacific

2018 SPECIAL PRINT EDITION www.ticotimes.net Surf, art and vibrant towns THE LURE OF COSTA RICA'S CENTRAL PACIFIC Granada (Nicaragua) LA CRUZ PUNTA SALINAS Garita LAGO DE Isla Bolaños Santa Cecilia NICARAGUA PUNTA DESCARTES Río Hacienda LOS CHILES PUNTA DE SAN ELENA Brasilia Volcán Orosí Birmania Santa Rita San José Playa Guajiniquil Medio Queso Boca del PUNTA río San Juan BLANCA Cuaniquil Delicias Dos Ríos Cuatro Bocas NICARAGUA PUNTA UPALA Playuelitas CASTILLA P.N. Santa Rosa Volcán Rincón de la Vieja Pavón Isla Murciélagos Río Negro García Flamenco Laguna Amparo Santa Rosa P.N. Rincón Canaleta Caño Negro Playa Nancite de la Vieja R.V.S. Playa Naranjo Aguas Claras Bijagua Caño Negro Río Pocosol Cañas Río Colorado Dulces Caño Ciego GOLFO DE Estación Volcán Miravalles Volcán Tenorio río Boca del Horizontes Guayaba F PAPAGAYO P.N. Volcán Buenavista San Jorge río Colorado Miravalles P.N. Volcán Río Barra del Colorado Pto. Culebra Fortuna SAN RAFAEL Isla Huevos Tenorio Río San Carlos DE GUATUZO Laurel Boca Tapada Río Colorado Canal LIBERIA Tenorio Sta Galán R.V.S. Panamá Medias Barra del Colorado Playa Panamá Salitral Laguna Cabanga Sto. Rosa Providencia Río Toro Playa Hermosa Tierras Cole Domingo Guardia Morenas San Gerardo Playa del Coco Venado Chambacú El Coco Chirripó Playa Ocotal Comunidad Río Tenorio Pangola Arenal Boca de Arenal Chaparrón o Boca del ria PUNTA GORDA BAGACES Rí río Tortuguero Ocotal ibe Caño Negro Boca Río Sucio Playa Pan de Azúcar Sardinal TILARÁN Veracruz San Rafael Playa Potrero Potrero L Río Tortuguero Laguna Muelle Altamira Muelle Playa Flamingo Río Corobici Volcán FILADELFIA R.B.