Gender Inequality in 600 Popular Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rambo: Last Blood Production Notes

RAMBO: LAST BLOOD PRODUCTION NOTES RAMBO: LAST BLOOD LIONSGATE Official Site: Rambo.movie Publicity Materials: https://www.lionsgatepublicity.com/theatrical/rambo-last-blood Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Rambo/ Twitter: https://twitter.com/RamboMovie Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/rambomovie/ Hashtag: #Rambo Genre: Action Rating: R for strong graphic violence, grisly images, drug use and language U.S. Release Date: September 20, 2019 Running Time: 89 minutes Cast: Sylvester Stallone, Paz Vega, Sergio Peris-Mencheta, Adriana Barraza, Yvette Monreal, Genie Kim aka Yenah Han, Joaquin Cosio, and Oscar Jaenada Directed by: Adrian Grunberg Screenplay by: Matthew Cirulnick & Sylvester Stallone Story by: Dan Gordon and Sylvester Stallone Based on: The Character created by David Morrell Produced by: Avi Lerner, Kevin King Templeton, Yariv Lerner, Les Weldon SYNOPSIS: Almost four decades after he drew first blood, Sylvester Stallone is back as one of the greatest action heroes of all time, John Rambo. Now, Rambo must confront his past and unearth his ruthless combat skills to exact revenge in a final mission. A deadly journey of vengeance, RAMBO: LAST BLOOD marks the last chapter of the legendary series. Lionsgate presents, in association with Balboa Productions, Dadi Film (HK) Ltd. and Millennium Media, a Millennium Media, Balboa Productions and Templeton Media production, in association with Campbell Grobman Films. FRANCHISE SYNOPSIS: Since its debut nearly four decades ago, the Rambo series starring Sylvester Stallone has become one of the most iconic action-movie franchises of all time. An ex-Green Beret haunted by memories of Vietnam, the legendary fighting machine known as Rambo has freed POWs, rescued his commanding officer from the Soviets, and liberated missionaries in Myanmar. -

Advisory System to Be Reevaluted Changes in Housing Policy

STATE HIOT SOC UF WISC 816 STATE ST NEW INTRAMURAL madison WISC SPORT - SEI INSIDE 51706 Vol. XCVII—No. 24 Lawrence University, Appleton, Wisconsin 549 FHday, 21 Aprii 1978 STATg HIOTPnirM — Faculty votes today on new interdisciplines program and use Chicago as the by Frank Massey year. Two other areas are now basis for further course work and The faculty will vote today on being considered and several research projects. the proposed addition of two new others are in the planning stage. Interdisciplinary areas may interdisciplinary areas to in The program was established also be assembled in computer cluded in next year’s course as an attempt to increase studies, environmental studies, catalogue. These are Urban curricular options open to Management of Complex Studies and Linguistics. Lawrence students. In most Organizations, and Comparative Linguistics is no longer offered areas there are five to seven Literature. as a major although students who courses offered, with either one Richard Warch, Vice-President have already declared a or two courses being required. for Academic Affairs, and the Linguistics major will be able The purpose of the required faculty involved are creating a courses is to give the area of to complete it. new way of approaching a course study a focal point and an overall Assoc. Prof. Richard Winslow of of study at Lawrence. A student the Linguistics committee feels coherence. will be able to gain perspective that this study will give the At present there are numerous and familiarity with a specific student an excellent background faculty members meeting area of interest and still fulfill the in Linguistics, sufficient to together and planning new in requirements of a maior. -

Suffragette Study Guide

© ATOM 2015 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-622-0 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Running time: 106 minutes » SUFFRAGETTE Suffragette (2015) is a feature film directed by Sarah Gavron. The film provides a fictional account of a group of East London women who realised that polite, law-abiding protests were not going to get them very far in the battle for voting rights in early 20th century Britain. click on arrow hyperlink CONTENTS click on arrow hyperlink click on arrow hyperlink 3 CURRICULUM LINKS 19 8. Never surrender click on arrow hyperlink 3 STORY 20 9. Dreams 6 THE SUFFRAGETTE MOVEMENT 21 EXTENDED RESPONSE TOPICS 8 CHARACTERS 21 The Australian Suffragette Movement 10 ANALYSING KEY SEQUENCES 23 Gender justice 10 1. Votes for women 23 Inspiring women 11 2. Under surveillance 23 Social change SCREEN EDUCATION © ATOM 2015 © ATOM SCREEN EDUCATION 12 3. Giving testimony 23 Suffragette online 14 4. They lied to us 24 ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS 15 5. Mrs Pankhurst 25 APPENDIX 1 17 6. ‘I am a suffragette after all.’ 26 APPENDIX 2 18 7. Nothing left to lose 2 » CURRICULUM LINKS Suffragette is suitable viewing for students in Years 9 – 12. The film can be used as a resource in English, Civics and Citizenship, History, Media, Politics and Sociology. Links can also be made to the Australian Curriculum general capabilities: Literacy, Critical and Creative Thinking, Personal and Social Capability and Ethical Understanding. Teachers should consult the Australian Curriculum online at http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ and curriculum outlines relevant to these studies in their state or territory. -

Makers: Women in Hollywood

WOMEN IN HOLLYWOOD OVERVIEW: MAKERS: Women In Hollywood showcases the women of showbiz, from the earliest pioneers to present-day power players, as they influence the creation of one of the country’s biggest commodities: entertainment. In the silent movie era of Hollywood, women wrote, directed and produced, plus there were over twenty independent film companies run by women. That changed when Hollywood became a profitable industry. The absence of women behind the camera affected the women who appeared in front of the lens. Because men controlled the content, they created female characters based on classic archetypes: the good girl and the fallen woman, the virgin and the whore. The women’s movement helped loosen some barriers in Hollywood. A few women, like 20th century Fox President Sherry Lansing, were able to rise to the top. Especially in television, where the financial stakes were lower and advertisers eager to court female viewers, strong female characters began to emerge. Premium cable channels like HBO and Showtime allowed edgy shows like Sex in the City and Girls , which dealt frankly with sex from a woman’s perspective, to thrive. One way women were able to gain clout was to use their stardom to become producers, like Jane Fonda, who had a breakout hit when she produced 9 to 5 . But despite the fact that 9 to 5 was a smash hit that appealed to broad audiences, it was still viewed as a “chick flick”. In Hollywood, movies like Bridesmaids and The Hunger Games , with strong female characters at their center and strong women behind the scenes, have indisputably proven that women centered content can be big at the box office. -

Scary Movie 5 (2013) Una Parodia a Tutto Campo Che Si Avvale Dell'efficace Ritmo Della Versione Italiana

Scary Movie 5 (2013) Una parodia a tutto campo che si avvale dell'efficace ritmo della versione italiana. Un film di Malcolm D. Lee con Lindsay Lohan, Charlie Sheen, Terry Crews, Kate Walsh, Ashley Tisdale, Jerry O'Connell, Molly Shannon, Heather Locklear, Chris Elliott, Simon Rex. Genere Commedia durata 85 minuti. Produzione USA 2013. Uscita nelle sale: giovedì 18 aprile 2013 Tra rivisitazioni geniali e battute a doppio senso, nel quinto episodio della saga demenziale horror più amata i protagonisti del cinema sono nuovamente sostituiti dalla loro folle controfigura. Giancarlo Zappoli - www.mymovies.it Dopo che Charlie Sheen (che interpreta se stesso) è stato ucciso da un fantasma nella sua camera da letto in cui si stava dando da fare con Lindsay Lohan (anche lei nei propri succinti panni) i suoi tre figli vengono rapiti e ritrovati dopo qualche tempo in un'abitazione nel bosco. Sono affidati allo zio Dan e a sua moglie Jody ma ben presto appare chiaro che con loro è entrato nella casa anche uno spirito malvagio. Così sia il lavoro di Dan (che sta testando droghe sugli scimpanzé per sviluppare la loro intelligenza) che le aspirazioni di Jody di diventare l'etoile nel balletto in cui danza subiscono forti interferenze. Parodia. Il Dizionario della Lingua Italiana Sabatini Colletti a questa voce precisa: "Versione comica, caricaturale di un'opera letteraria, di una canzone, di un film". Dal lontano 2000 quando i Wayans, Jason Friedberg, Aaron Seltzer si divertirono a divertire il pubblico con sberleffi mirati ai film horror di successo dell'epoca, con cadenza regolare la parodia dei blockbuster non solo orrorifici ha i suoi appassionati fan. -

Holiday TV Guide 2020

HolidayTV Better watch out 20th Century Fox Thirty years after premiering in theaters, this movie about a boy who protects his home from burglars at Christmastime is still entertaining viewers young and old. Kevin McCallister (Macaulay Culkin, “My Girl,” 1991) learns to be careful what he wishes for after his mom and dad accidentally leave him behind as they fly to Paris for the holidays in “Home Alone,” airing Thursday, Nov. 26, on Freeform. Holiday TV| Home Alone 30th Anniversary 30 years of holiday high jinx ‘Home Alone’ celebrates big milestone By Kyla Brewer TV Media their extended family scramble to make it to the airport in time to catch their flight. In the ensuing chaos and confusion, parents Kate (Catherine he holidays offer movie fans a treasure O’Hara, “Schitt’s Creek”) and Peter (John Heard, trove of options, old and new. Some are “Cutter’s Way,” 1981) forget young Kevin, who Tfunny, some are heartwarming, some are had been sent to sleep in the attic after causing a inspirational and a precious few are all of those ruckus the night before. The boy awakens to find things combined. One such modern classic is cel- his home deserted and believes that his wish for ebrating a milestone this year, and viewers won’t his family to disappear has come true. want to miss it. At first, Kevin’s new parent-and-sibling-free Macaulay Culkin (“My Girl,” 1991) stars as Kevin existence seems ideal as he jumps on his parents’ McCallister, a boy who is left behind when his fam- bed, raids his big brother’s room, eats ice cream ily goes on vacation during the holidays, in “Home for supper and watches gangster movies. -

Seawood Village Movies

Seawood Village Movies No. Film Name 1155 DVD 9 1184 DVD 21 1015 DVD 300 348 DVD 1408 172 DVD 2012 704 DVD 10 Years 1175 DVD 10,000 BC 1119 DVD 101 Dalmations 1117 DVD 12 Dogs of Christmas: Great Puppy Rescue 352 DVD 12 Rounds 843 DVD 127 Hours 446 DVD 13 Going on 30 474 DVD 17 Again 523 DVD 2 Days In New York 208 DVD 2 Fast 2 Furious 433 DVD 21 Jump Street 1145 DVD 27 Dresses 1079 DVD 3:10 to Yuma 1124 DVD 30 Days of Night 204 DVD 40 Year Old Virgin 1101 DVD 42: The Jackie Robinson Story 449 DVD 50 First Dates 117 DVD 6 Souls 1205 DVD 88 Minutes 177 DVD A Beautiful Mind 643 DVD A Bug's Life 255 DVD A Charlie Brown Christmas 227 DVD A Christmas Carol 581 DVD A Christmas Story 506 DVD A Good Day to Die Hard 212 DVD A Knights Tale 848 DVD A League of Their Own 856 DVD A Little Bit of Heaven 1053 DVD A Mighty Heart 961 DVD A Thousand Words 1139 DVD A Turtle's Tale: Sammy's Adventure 376 DVD Abduction 540 DVD About Schmidt 1108 DVD Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter 1160 DVD Across the Universe 812 DVD Act of Valor 819 DVD Adams Family & Adams Family Values 724 DVD Admission 519 DVD Adventureland 83 DVD Adventures in Zambezia 745 DVD Aeon Flux 585 DVD Aladdin & the King of Thieves 582 DVD Aladdin (Disney Special edition) 496 DVD Alex & Emma 79 DVD Alex Cross 947 DVD Ali 1004 DVD Alice in Wonderland 525 DVD Alice in Wonderland - Animated 838 DVD Aliens in the Attic 1034 DVD All About Steve 1103 DVD Alpha & Omega 2: A Howl-iday 785 DVD Alpha and Omega 970 DVD Alpha Dog 522 DVD Alvin & the Chipmunks the Sqeakuel 322 DVD Alvin & the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked -

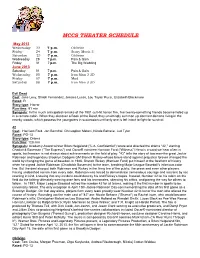

Mccs Theater Schedule

MCCS THEATER SCHEDULE May 2013 Wednesday 22 7 p.m. Oblivion Friday 24 7 p.m. Scary Movie 5 Saturday 25 7 p.m. Oblivion Wednesday 29 7 p.m. Pain & Gain Friday 31 7 p.m. The Big Wedding June 2013 Saturday 01 7 p.m. Pain & Gain Wednesday 05 7 p.m. Iron Man 3 3D Friday 07 7 p.m. Mud Saturday 08 7 p.m. Iron Man 3 3D Evil Dead Cast: Jane Levy, Shiloh Fernandez, Jessica Lucas, Lou Taylor Pucci, Elizabeth Blackmore Rated: R Story type: Horror Run time: 91 min Synopsis: In the much anticipated remake of the 1981 cult-hit horror film, five twenty-something friends become holed up in a remote cabin. When they discover a Book of the Dead, they unwittingly summon up dormant demons living in the nearby woods, which possess the youngsters in succession until only one is left intact to fight for survival. 42 Cast: Harrison Ford, Jon Bernthal, Christopher Meloni, Nicole Beharie, Jud Tylor Rated: PG-13 Story type: Drama Run time: 128 min Synopsis: Academy Award winner Brian Helgeland ("L.A. Confidential") wrote and directed the drama "42," starring Chadwick Boseman ("The Express") and OscarR nominee Harrison Ford ("Witness").Hero is a word we hear often in sports, but heroism is not always about achievements on the field of play. "42" tells the story of two men-the great Jackie Robinson and legendary Brooklyn Dodgers GM Branch Rickey-whose brave stand against prejudice forever changed the world by changing the game of baseball. In 1946, Branch Rickey (Harrison Ford) put himself at the forefront of history when he signed Jackie Robinson (Chadwick Boseman) to the team, breaking Major League Baseball's infamous color line. -

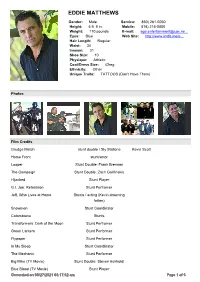

Eddie Matthews

EDDIE MATTHEWS Gender: Male Service: 850) 261-0050 Height: 5 ft. 9 in. Mobile: 818) 216-0800 Weight: 170 pounds E-mail: [email protected]... Eyes: Blue Web Site: http://www.imdb.me/e... Hair Length: Regular Waist: 34 Inseam: 31 Shoe Size: 10 Physique: Athletic Coat/Dress Size: 42reg Ethnicity: Other Unique Traits: TATTOOS (Don't Have Them) Photos Film Credits Grudge Match stunt double / Sly Stallone Kevin Scott Home Front stunt/actor Looper Stunt Double: Frank Brennan The Campaign Stunt Double: Zach Galifinakis Hijacked Stunt Player G.I. Joe: Retaliation Stunt Perfromer Jeff, Who Lives at Home Stunts / acting (Kevin drowning father) Snowmen Stunt Coordinator Colombiana Stunts Transformers: Dark of the Moon Stunt Perfromer Green Lantern Stunt Performer Flypaper Stunt Performer In My Sleep Stunt Coordinator The Mechanic Stunt Performer Big Mike (TV Movie) Stunt Double: Steven Eckholdt Blue Blood (TV Movie) Stunt Player Generated on 09/27/2021 03:17:52 am Page 1 of 5 Transit Stunt Perfomer Jonah Hex Stunts The Final Destination Stunts 12 Rounds Stunt Player Jolene Stunt Coordiantor: Arizona You Don't Mess with the Zohan Stunt Player A House Divide Stunt Player The Kingdom Stunt Player Rush Hour 3 Stunts Pride Stunts The Hitcher Stunts Letters from Iwo Jima Stunt Perfromer Flags of Our Fathers Stunts The Guardian Stunts Miami Vice Stunts The Plaeasure Drivers Stunt Coordinator Wasted Stunt Coordinator The Dukes of Hazzard Stunt Performer Faith of My Fathers (TV Movie) Stunt Double: John McCain After the Sunset Stunts The Long Ride -

The Providence Phoenix | February 22, 2013 3

february 22–28, 2013 | rhode island’s largest weekly | free VOTE NOW! support your favorites at thephoenix. com/best THE NEW ABOLITIONISTS Why the climate-justice movement must embrace its radical side _by Wen Stephenson | p 6 tHis drum circles and porn beer on a budget Just in A weekend at the RI Men’s Gathering | p6 !Warming up to ‘craft lite’ | p10 North Bowl has been nominated by The Phoenix readers for: BEST PLACE TO BOWL Please vote for us! SCAN HERE Or vote online: thephoenix.com/BEST 71 E Washington St North Attleboro, MA 02760 508.695.BOWL providence.thephoenix.com | the providence phoenix | February 22, 2013 3 february 22, 2013 Contents on the cover F PHOTO-ILLUSTRATION By jANET SMITH TAyLOR IN THIS ISSUE p 6 p 10 p 24 6 the new abolitionists _wen stephenson For the second time in American history, a generation has to choose between an entrenched system of industrial profit — and saving millions of human lives. 14 homegrown product _by chris conti All killer, no filler: theo martins offers a guided tour of Wonderland. 15 art _by chris conti Serious comics: “story/line: narrative form in six graphic novelists” at RIC. 16 theater _by bill rodriguez Mind games: Epic Theatre Company’s six degrees of separation. 24 film _by peter keough If Argo doesn’t win the Oscar for Best Picture, it means the terrorists have won. Plus, a “Short Take” on identity thief. IN EVERY ISSUE 46 phillipe & Jorge’s cool, cool world Ronzo gets the boot | Public enemy #1 | Who’s right, who’s wrong? | 6 Seekonk rocks 4 the city _by derf 7 5 this Just in In the woods with the Rhode Island 10 Men’s Gathering | WPRO cans Ron St. -

Florida Southern College Assessing the Vanishing Lesbian in Book-To

Florida Southern College Assessing the Vanishing Lesbian in Book-to-Film Adaptations: A Critical Study of Rebecca, Fried Green Tomatoes, and Black Panther Felicia Coursen Thesis Advisor: Dr. Moffitt May 2, 2021 Coursen 2 A Framework for Understanding the Vanishing Lesbian Popular media consistently disregards lesbian voices and identities. The film industry, as a facet of popular media, often neglects to tell lesbian stories. When films do include lesbian characters, the depictions are often problematic and grounded in stereotypes. Literary critic and queer theorist Terry Castle argues the following in her book, The Apparitional Lesbian: Female Homosexuality and Modern Culture: “The lesbian remains a kind of ‘ghost effect’ in the cinema world of modern life: elusive, vaporous, difficult to spot – even when she is there, in plain view, mortal and magnificent, at the center of the screen. Some may even deny she exists at all” (2). Castle explains the “ghost effect” of lesbian characters in cinema, which is better identified as the process of lesbian erasure. Although the two terms are synonymous, “lesbian erasure” provides a more clear-cut verbalization of this process (i.e., there once were lesbian characters, but they are now erased). Lesbian erasure is a direct result of the following: (1) the absence of lesbian characters, (2) the inclusion of only one-dimensional/stereotyped lesbian representation, and/or (3) the use of subversion and subtextualization to hide lesbian characters from audiences. Book-to-film adaptations reveal the ghost effect most clearly. Lesbians in book-to-film adaptations are not only apparitional; they vanish right before the viewers’ eyes. -

The Evolution of Fat Female Characters in Contemporary American Film a Thesis Presented to the Faculty Of

Changing Shape: The Evolution of Fat Female Characters in Contemporary American Film A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Laura E. Pohlman April 2016 © 2016 Laura E. Pohlman. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Changing Shape: The Evolution of Fat Female Characters in Contemporary American Film by LAURA E. POHLMAN has been approved for the School of Film and the College of Fine Arts by Ofer Eliaz Assistant Professor of Film Studies Elizabeth Sayrs Interim Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 Abstract LAURA E. POHLMAN, M.A., April 2016, Film Changing Shape: The Evolution of Fat Female Characters in Contemporary American Film Director of Thesis: Ofer Eliaz The purpose of this thesis is to elucidate the fluid conception of fat women within contemporary American culture from the early 1970s to the present. Due to their non- normative embodiment, fat women typically face denigration and marginalization. Most mainstream film narratives reify the negative social positioning of fat women, often through assimilationist characters that resign themselves to fatphobia or otherwise compensate for their fatness. On the flipside, carnival and camp narratives foster liberatory fat characterization, as exemplified by the figure of “the unruly woman.” In his portrayal of both assimilationist and liberationist women, Divine functions as a barometer for subsequent fat characterization. Overall, this thesis critiques fat assimilation, argues for the importance of fat liberation, and projects a future where fat acceptance becomes the norm. 4 Table of Contents Page Abstract ..............................................................................................................................