Saving Lives Today and Tomorrow: Managing the Risk Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disasters, Climate Change and Human Mobility in Southern Africa: Consultation on the Draft Protection Agenda

DISASTERS, CLIMATE CHANGE AND HUMAN MOBILITY IN SOUTHERN AFRICA: CONSULTATION ON THE DRAFT PROTECTION AGENDA BACKGROUND PAPER South Africa Regional Consultation in cooperation with the Development and Rule of Law Programme (DROP) at Stellenbosch University Stellenbosch, South Africa, 4-5 June 2015 DISASTERS CLIMATE CHANGE AND DISPLACEMENT EVIDENCE FOR ACTION NORWEGIAN NRC REFUGEE COUNCIL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Southern Africa Consultation will be hosted by the Development and Rule of Law Programme (DROP) at Stellenbosch University in South Africa and co-organized in partnership with the Nansen Initiative Secretariat and the Norwegian Refugee Council. The project is funded by the European Union with the support of Norway and Switzerland Federal Department of Foreign Aairs FDFA CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................6 1.1 Background to the Nansen Initiative Southern Africa Consultation ...............................................................................7 1.2 Objectives of the Southern Africa Consultation ............................................................................................................7 2. OVERVIEW OF DISASTERS AND HUMAN MOBILITY IN SOUTHERN AFRICA ..............................................................9 2.1 Natural Hazards and Climate Change in Southern Africa ............................................................................................10 2.2 Challenge -

Climate Disasters in the Philippines: a Case Study of the Immediate Causes and Root Drivers From

Zhzh ENVIRONMENT & NATURAL RESOURCES PROGRAM Climate Disasters in the Philippines: A Case Study of Immediate Causes and Root Drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi Benjamin Franta Hilly Ann Roa-Quiaoit Dexter Lo Gemma Narisma REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 Environment & Natural Resources Program Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org/ENRP The authors of this report invites use of this information for educational purposes, requiring only that the reproduced material clearly cite the full source: Franta, Benjamin, et al, “Climate disasters in the Philippines: A case study of immediate causes and root drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi.” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University, November 2016. Statements and views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, the Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Design & Layout by Andrew Facini Cover photo: A destroyed church in Samar, Philippines, in the months following Typhoon Yolanda/ Haiyan. (Benjamin Franta) Copyright 2016, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America ENVIRONMENT & NATURAL RESOURCES PROGRAM Climate Disasters in the Philippines: A Case Study of Immediate Causes and Root Drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi Benjamin Franta Hilly Ann Roa-Quiaoit Dexter Lo Gemma Narisma REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 The Environment and Natural Resources Program (ENRP) The Environment and Natural Resources Program at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs is at the center of the Harvard Kennedy School’s research and outreach on public policy that affects global environment quality and natural resource management. -

On the Ball! One of the Most Recognizable Stars on the U.S

TVhome The Daily Home June 7 - 13, 2015 On the Ball! One of the most recognizable stars on the U.S. Women’s World Cup roster, Hope Solo tends the goal as the U.S. 000208858R1 Women’s National Team takes on Sweden in the “2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup,” airing Friday at 7 p.m. on FOX. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., June 7, 2015 — Sat., June 13, 2015 DISH AT&T CABLE DIRECTV CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA SPORTS BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING 5 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 Championship Super Regionals: Drag Racing Site 7, Game 2 (Live) WCIQ 7 10 4 WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Monday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 8 p.m. ESPN2 Toyota NHRA Sum- 12 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 mernationals from Old Bridge Championship Super Regionals Township Race. -

Supply Chain Operations Management in Pandemics: a State-Of-The-Art Review Inspired by COVID-19

sustainability Review Supply Chain Operations Management in Pandemics: A State-of-the-Art Review Inspired by COVID-19 Muhammad Umar Farooq 1,2,* , Amjad Hussain 1,*, Tariq Masood 3,4 and Muhammad Salman Habib 1 1 Department of Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering, University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore 54890, Pakistan; [email protected] 2 Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Daejeon 34141, Korea 3 Department of Engineering, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 1PZ, UK; [email protected] 4 Department of Design, Manufacturing and Engineering Management, University of Strathclyde, 75 Montrose Street, Glasgow G1 1XJ, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.U.F.); [email protected] (A.H.); Tel.: +92-304-887-3688 (M.U.F.) Abstract: Pandemics cause chaotic situations in supply chains (SC) around the globe, which can lead towards survivability challenges. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is an unprecedented humanitarian crisis that has severely affected global business dynamics. Similar vulnerabilities have been caused by other outbreaks in the past. In these terms, prevention strategies against propagating disruptions require vigilant goal conceptualization and roadmaps. In this respect, there is a need to explore supply chain operation management strategies to overcome the challenges that emerge due to COVID-19-like situations. Therefore, this review is aimed at exploring such challenges and developing strategies for sustainability, and viability perspectives for SCs, through a structured literature review (SLR) approach. Moreover, this study investigated the impacts of previous epidemic Citation: Farooq, M.U.; Hussain, A.; outbreaks on SCs, to identify the research objectives, methodological approaches, and implications Masood, T.; Habib, M.S. -

2009-06-19.Pdf2013-02-12 15:4710.7 MB

aminammr • MI • h drtnht, 8 p.. I Crnd=ICdIdStr rf:ht, 8 p.. th (. hrd, n 2th ( (- 4 .. tlIrtlddllrStndY nht, 8 p. I fn 2 , „ s n Snd th Anbrln, ll h rd n 26th AMO EAC • SICE 1599 t Gnllr. fr h & tt nfrtn nr AC jU ISIE: I ISIGS SEE AGES AAAI 62 IAY, UE , 200 l. . 2 24 • AMOEWS I O AMO I YE I AMO AS I EEE SAAM I SEAOOK EAS KIGSO I SOU AMO I EACES Cnnll Cntn C ,, I .Atlnt. I P.O. Box 592, Hampton, NH 03843 I (60 26 4557 I EE • AKE OE ' To r. brt tr hft r t rtr, bt h nt bt t l dn lOS0 - It bn ln nd ndn rd, bt ftr r thn • thr dd, t fnll t tO hn ln. Wh nt d t n jdrppn ndppl 4 Ch■ - I - h r plt xvth pr . bnn hv d, hnn fr th rr v rrr. And hl tht rrr lt th drvr l bhnd, n t nt nl ■ fr rfltn, bt l t t face frrd. .1.."4. .,d, n 0 r. brt .tr ••• I EfOn tt (Wfttlt I II I I ll IM : , lo• If, In 0 . . Ut Or Cplt EOW nrv llOb t. UE EIE MIAIO AEIO UES n S, n 2th, p rph fr ShCr Ctsinldn lnbnlff —.sm • SOW i ? WICKE AE Ctr: t AAA I t d tr• I lntll . r I ..:It I .. ItC . OES O IES AGE 2A I AAr. EWS I UE , 200 I O , 2 SO OCA I SAE lOS COMMUIY Ar r d rd t b vr t? MAK CAG . -

Mozambique Fieldwork Report

Strategic Research into National and Local Capacity Building for DRM Mozambique Fieldwork Report Roger Few, Zoë Scott, Kelly Wooster, Mireille Flores Avila, Marcela Tarazona, Antonio Queface and Alberto Mavume. June 2015 Mozambique Fieldwork Report Acknowledgements The OPM Research Team would like to express sincere thanks to Roberto White from GFDRR Mozambique, Joao Ribeiro from INGC and Wild do Rosário from UN-Habitat for sharing their time and resources. We would also like to thank Joczabet Guerrero and Konstanze Kamojer for their invaluable advice and guidance in relation to the GIZ PRO-GRC project. Finally, we would like to thank all those interviewees and workshop attendees who freely gave their time, expert opinion and enthusiasm, and to Antonio Beleza who assisted the team during the fieldwork. This assessment is being carried out by Oxford Policy Management and the University of East Anglia. The Project Manager is Zoë Scott and the Research Director is Roger Few. For further information contact [email protected] Oxford Policy Management Limited 6 St Aldates Courtyard Tel +44 (0) 1865 207 300 38 St Aldates Fax +44 (0) 1865 207 301 Oxford OX1 1BN Email [email protected] Registered in England: 3122495 United Kingdom Website www.opml.co.uk © Oxford Policy Management i Mozambique Fieldwork Report Table of Contents Acknowledgements i List of Boxes and Tables 3 List of Abbreviations 4 1 Introduction and methodology 7 1.1 Introduction to the research 7 1.2 Methodology 8 1.2.1 Data collection tools 9 1.2.2 Case study procedure 10 1.2.3 -

Daily Sun Article

South African Weather Service Watching the Weather to Protect Life and Property Strong winds and other kinds of rough weather can destroy WHOWHO WE WE ARE ARE houses and lives . THE South African Weather Service is the advanced equipment that aids us in the national provider of weather and climate-re- monitoring and prediction of weather pat- lated information. terns and the collection of climatic-related The past 10 years has seen an increase in information. weather-related natural disasters that have Our improved national weather observa- affected the lives of local communities. tion network has resulted in more accurate The deaths, injuries and damage to prop- weather and climate information, that helps erty caused have hampered sustainable de- us to provide bad weather early warning sys- velopment in both urban and rural commu- tems to the Republic of South Africa. nities, and we play an important role in The South African Weather Service is at helping the South African government to the forefront of providing weather and cli- lessen the effects of weather-related natural mate information in South Africa and we are disasters. confident that the years ahead will see even As an organisation, we are committed to more measures being developed to help pro- reducing the impact of these disasters by in- tect the South African public and keep vesting in the latest and most technologically weather related damage to a minimum. CELEBRATE WORLD METEOROLOGICAL DAY EACH year, on 23 March, the World Meteoro- a specialised agency of the United Nations. resulting distribution of water resources. community to see that that important weather logical Organisation (WMO) – a United Nations The theme for World Meteorological Day South Africa is represented at WMO by the and climate information is available and accessi- organisationwith189members–andtheworld- 2013 is “Watching the Weather to Protect Life CEO of the South African Weather Service ble for global programmes. -

Humanitarianism in Crisis

UNIteD StAteS INStItUte of Peace www.usip.org SPeCIAL RePoRt 2301 Constitution Ave., NW • Washington, DC 20037 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPO R T Søren Jessen-Petersen The militarization and politicization of humanitarian efforts have led to diminishing effectiveness on the ground and greater dangers for humanitarian workers, leaving humanitarian action in a state of crisis. Without a vigorous restatement of the principles of humanitarianism and a concerted effort by the international community to address the causes of this crisis, humanitarian Humanitarianism action will, as this report concludes, progressively become a tool selectively used by the powerful and possibly fail in its global mission of protecting and restoring the dignity of human life. in Crisis ABOUT THE AUTHO R Søren Jessen-Petersen is a former assistant high commissioner Summary for refugees in the office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and UN special representative for Kosovo. • With the end of the Cold War, internal conflicts targeting civilian populations proliferated. As He has served UNHCR in Africa and the Balkans as well as international political institutions struggled to figure out how to deal with these conflicts, at its headquarters in Geneva and New York. He is currently humanitarian action often became a substitute for decisive political action or, more worryingly, teaching migration and security at the School of Foreign was subsumed under a political and military agenda. Service, Georgetown University, and at the School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University. He was a • The increasing militarization and politicization of humanitarian efforts have led to growing Jennings Randolph guest scholar at the United States Institute ineffectiveness of humanitarian action on the ground and greater dangers for humanitarian of Peace from November 2006 to June 2009. -

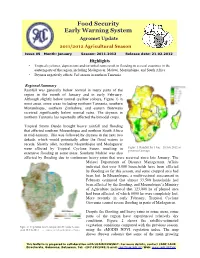

Agromet Update Issue 04

Food Security Early Warning System Agromet Update 2011/2012 Agricultural Season Issue 05 Month: January Season: 2011-2012 Release date: 21-02-2012 Highlights • Tropical cyclones, depressions and torrential rains result in flooding in several countries in the eastern parts of the region, including Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique, and South Africa • Dryness negatively affects Vuli season in northern Tanzania Regional Summary Rainfall was generally below normal in many parts of the region in the month of January and in early February. Although slightly below normal (yellow colours, Figure 1) in most areas, some areas including northern Tanzania, southern Mozambique, southern Zimbabwe, and eastern Botswana received significantly below normal rains. The dryness in northern Tanzania has reportedly affected the bimodal crops. Tropical Storm Dando brought heavy rainfall and flooding that affected southern Mozambique and northern South Africa in mid-January. This was followed by dryness in the next two dekads, which would potentially allow the flood waters to recede. Shortly after, northern Mozambique and Madagascar were affected by Tropical Cyclone Funso, resulting in Figure 1. Rainfall for 1 Jan – 10 Feb 2012 as percent of average extensive flooding in some areas. Southern Malawi was also affected by flooding due to continuous heavy rains that were received since late January. The Malawi Department of Disaster Management Affairs indicated that over 5,000 households have been affected by flooding so far this season, and some cropped area had been lost. In Mozambique, a multi-sectoral assessment in February estimated that almost 33,500 households had been affected by the flooding, and Mozambique’s Ministry of Agriculture indicated that 123,000 ha of planted area had been affected, of which 6000 ha were completely lost. -

Malawi 10-Day Rainfall & Agrometeorological Bulletin

Malawi 10-Day Rainfall & Agrometeorological Bulletin Department of Climate Change and Meteorological Services Period: 21 – 31 January 2012 Season: 2011/2012 Issue No.12 Release date: 3rd February 2012 HIGHLIGHTS • Above average rains recorded in the south and light to moderate elsewhere… • Heavy floods wreck houses, crops and livestock in lower Shire districts… • Widespread rains are expected over Malawi during first ten days of February 2012… All inquiries should be addressed to: The Director of Climate Change and Meteorological Services, P.O. Box 1808, Blantyre, MALAWI Tel: (265) 1 822 014/106 Fax: (265) 1 822 215 E-mail: [email protected] Homepage: www.metmalawi.com Period: 21 – 31 January 2012 Season: 2011/12 Issue No 12 1.1 RAINFALL SITUATION relative humidity values ranged from 69% at Karonga to 87% at Makoka in Zomba. More details are on the During the last ten days of January 2012, shallow Congo Table 2. Air mass caused light and below average rainfall (yellow and brown colours on Map 1) along the lakeshore and 1.6 MEAN SUNSHINE HOURS other areas of central and northern Malawi while Tropical cyclone FUNSO in Mozambique Channel Malawi experienced cloudy to overcast skies during the caused torrential rains particularly over the catchment period under review. Reports from sampled stations area of Shire River in southern Malawi, triggering indicate that daily average sunshine hours ranged from 1.1 flooding downstream hours of bright sunshine at Bvumbwe to 4.6 hours at in the lower Shire Mzimba Met station. districts of Chikhwawa and Nsanje during the 2. AGROMETEOROLOGICAL ASSESSMENT first half of the period under review. -

Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2013

GLOBAL HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE REPORT 2013 GLOBAL HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE Report 2013 Acknowledgements Thank you The Global Humanitarian Assistance (GHA) team would like to thank the many people who have been involved in helping us put the GHA report 2013 together: our colleagues at Development Initiatives; Diane Broadley of Broadley Design; Jon Lewis at Essential Print Management for his role in production; Lydia Poole for peer reviewing; Lisa Walmsley for research on the 'How technology can improve response' section; Velina Stoianova for research and analysis into private humanitarian funding. We would like to thank the programme’s funders for their continued support: the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA); the Human Rights, Good Governance and Humanitarian Aid Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Netherlands; the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida), Sweden; and the Department for International Development (DFID), the United Kingdom. The GHA report 2013 was co-authored by Oliver Buston (Consultant) and Kerry Smith (Programme Manager) with extensive data analysis and research from GHA team members: Chloe Stirk, Dan Sparks, Daniele Malerba (Data Lead) and Hannah Sweeney, while Jenny Claydon coordinated editorial production. Editorial guidance was provided by Executive Directors, Judith Randel and Tony German, and Director of Research, Analysis and Evidence, Dan Coppard. Contents Foreword 2 Executive summary 3 Part 1: Humanitarian response to crisis 9 1. How much humanitarian assistance was given? 11 How much was needed? 12 Was enough given? 14 2. Where does humanitarian assistance come from? 19 Government donors 20 In focus: Gulf States 28 Individual and private donors 30 Domestic government response 34 In focus: Turkey 36 3. -

Guideline ADDRESSING HIV in HUMANITARIAN SETTINGS

Guideline ADDRESSING HIV IN HUMANITARIAN SETTINGS March 2010 IASC Task Force on HIV Endorsed by: IASC Principals 2010 GUIDELINES for Addressing HIV in Humanitarian Settings IASC Inter-Agency Standing Committee UNAIDS/10.03E / JC1767E (English original, March 2010) ISBN 978 92 9 173849 6 Photos credit: Front cover: IRIN / A. Graham Back cover: UNHCR / P. Wiggers GUIDELINES for Addressing HIV in Humanitarian Settings IASC Inter-Agency Standing Committee ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Task Force on HIV wishes to thank all the people who collaborated on the development of these guidelines and who gave generously of their time and experience. The Task Force would also like to acknowledge the support received from colleagues within the different agencies and all the nongovernmental organiza- tions that participated in the continuous review of the document. These guidelines were developed through an interagency process with participation by United Nations (UN) organiza- tions, nongovernmental organizations, the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and the International Organization for Migration. The IASC was established in 1992 in response to UN General Assembly resolution 46/182, which called for strengthened coordination of humanitarian assistance. The resolution set up the IASC as the primary mechanism for facilitating intera- gency decision-making in response to complex emergencies and natural disasters. The IASC comprises representatives of a broad range of UN and non-UN humanitarian partners, including UN agencies, nongovernmental organizations and organizations such as the World Bank and the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. Page 2 FOREWORD In 2004, the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) issued the guidelines Addressing HIV/AIDS Interventions in Emergency Settings to help guide those involved in emergency response, and those responding to the epidemic, to plan the delivery of a minimum set of HIV prevention, care and support interventions to people affected by humanitarian crises.