Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Climate Disasters in the Philippines: a Case Study of the Immediate Causes and Root Drivers From

Zhzh ENVIRONMENT & NATURAL RESOURCES PROGRAM Climate Disasters in the Philippines: A Case Study of Immediate Causes and Root Drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi Benjamin Franta Hilly Ann Roa-Quiaoit Dexter Lo Gemma Narisma REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 Environment & Natural Resources Program Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org/ENRP The authors of this report invites use of this information for educational purposes, requiring only that the reproduced material clearly cite the full source: Franta, Benjamin, et al, “Climate disasters in the Philippines: A case study of immediate causes and root drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi.” Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University, November 2016. Statements and views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, the Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Design & Layout by Andrew Facini Cover photo: A destroyed church in Samar, Philippines, in the months following Typhoon Yolanda/ Haiyan. (Benjamin Franta) Copyright 2016, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America ENVIRONMENT & NATURAL RESOURCES PROGRAM Climate Disasters in the Philippines: A Case Study of Immediate Causes and Root Drivers from Cagayan de Oro, Mindanao and Tropical Storm Sendong/Washi Benjamin Franta Hilly Ann Roa-Quiaoit Dexter Lo Gemma Narisma REPORT NOVEMBER 2016 The Environment and Natural Resources Program (ENRP) The Environment and Natural Resources Program at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs is at the center of the Harvard Kennedy School’s research and outreach on public policy that affects global environment quality and natural resource management. -

On the Ball! One of the Most Recognizable Stars on the U.S

TVhome The Daily Home June 7 - 13, 2015 On the Ball! One of the most recognizable stars on the U.S. Women’s World Cup roster, Hope Solo tends the goal as the U.S. 000208858R1 Women’s National Team takes on Sweden in the “2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup,” airing Friday at 7 p.m. on FOX. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., June 7, 2015 — Sat., June 13, 2015 DISH AT&T CABLE DIRECTV CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA SPORTS BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING 5 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 Championship Super Regionals: Drag Racing Site 7, Game 2 (Live) WCIQ 7 10 4 WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Monday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 8 p.m. ESPN2 Toyota NHRA Sum- 12 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 mernationals from Old Bridge Championship Super Regionals Township Race. -

2009-06-19.Pdf2013-02-12 15:4710.7 MB

aminammr • MI • h drtnht, 8 p.. I Crnd=ICdIdStr rf:ht, 8 p.. th (. hrd, n 2th ( (- 4 .. tlIrtlddllrStndY nht, 8 p. I fn 2 , „ s n Snd th Anbrln, ll h rd n 26th AMO EAC • SICE 1599 t Gnllr. fr h & tt nfrtn nr AC jU ISIE: I ISIGS SEE AGES AAAI 62 IAY, UE , 200 l. . 2 24 • AMOEWS I O AMO I YE I AMO AS I EEE SAAM I SEAOOK EAS KIGSO I SOU AMO I EACES Cnnll Cntn C ,, I .Atlnt. I P.O. Box 592, Hampton, NH 03843 I (60 26 4557 I EE • AKE OE ' To r. brt tr hft r t rtr, bt h nt bt t l dn lOS0 - It bn ln nd ndn rd, bt ftr r thn • thr dd, t fnll t tO hn ln. Wh nt d t n jdrppn ndppl 4 Ch■ - I - h r plt xvth pr . bnn hv d, hnn fr th rr v rrr. And hl tht rrr lt th drvr l bhnd, n t nt nl ■ fr rfltn, bt l t t face frrd. .1.."4. .,d, n 0 r. brt .tr ••• I EfOn tt (Wfttlt I II I I ll IM : , lo• If, In 0 . . Ut Or Cplt EOW nrv llOb t. UE EIE MIAIO AEIO UES n S, n 2th, p rph fr ShCr Ctsinldn lnbnlff —.sm • SOW i ? WICKE AE Ctr: t AAA I t d tr• I lntll . r I ..:It I .. ItC . OES O IES AGE 2A I AAr. EWS I UE , 200 I O , 2 SO OCA I SAE lOS COMMUIY Ar r d rd t b vr t? MAK CAG . -

The Year That Shook the Rich: a Review of Natural Disasters in 2011

THE YEAR THAT SHOOK THE RICH: A REVIEW OF NATURAL DISASTERS IN 2011 The Brookings Institution – London School of Economics Project on Internal Displacement March 2012 Design: [email protected] Cover photo: © Thinkstock.com Back cover photos: left / © Awcnz62 | Dreamstime.com; right / © IOM 2011 - MPK0622 (Photo: Chris Lom) THE YEAR THAT SHOOK THE RICH: A REVIEW OF NATURAL DISASTERS IN 2011 By Elizabeth Ferris and Daniel Petz March 2012 PUBLISHED BY: THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION – LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS PROJECT ON INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT Bangkok, Thailand — Severe monsoon floods, starting in late July 2011, affected millions of people. A truck with passengers aboard drives through a heavily flooded street. Photo: UN/Mark Garten TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronyms ................................................................................................................................. vi Foreword ................................................................................................................................. ix Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. xi Introduction .............................................................................................................................. xv Chapter 1 The Year that Shook the Rich ...................................................... 1 Section 1 Disasters in the “Rich” World, Some Numbers ............................................ 5 Section 2 Japan: The Most Expensive Disaster -

2009-04-03.Pdf2013-02-12 15:4713.6 MB

AOME & GAE UOU SECIO ISIE: TV LANTIC ISIGS IAY, AI , 200 rntdNEWS I Et Kntn I Extr I Grnlnd I ptn I ptn h I ptn ll l. 2 I 6 Knntn I vvfld I rth ptn I I h I Sbr I Sth ptn I Strth Cnnll Cntn C 4 I .Atlnt. I .O. x 2, ptn, 084 I (60 26 4 I FREE • TAKE ONE flrtptt GEE GU — , tht ll nt rll rn, bt rnzr f th pn Erth W vnt n ptn r hpn t hlp rt rnr St nt th vrt f rthfrndl vnt. — Atlnt ht Illtrtn b rh lln Erth W lbrtn dnd t npr, dt Y MAK (AG . nr, f r, tht, n th nvrnntll nl d lbrtn, bt AAIC EWS SA WIE Evr d Chldrn n t, ndd b flld th rthl vr hld h d ." Erth ? tvt t npr, ntrtn th tn, nd tht phl ht ht trl nd dt. E l rvd th ph nd ppl t t th xpl rp f vlntr n p Erth W, t h nr. n n pplrt f Erth tn r prpn, th t b nn, th brnhld "Wh thr Mthr . Wh hld t fll nl r nl rnd th f th ptn h nd thr , bt n nl d n Aprl n l t lbrt th r tftn Ctt, hh nt Chldrn ?" h r? Shldnt vr d, Erth th nt nl h bn plnnn th r EA WEE Cnt. n 8A, AGE 2A AAc EWS I AMU , 200 I oi_ , o 2 AAICEWS.COM COMMUIY rnn rt t th bl Y I EMO been impressed with' the have been made by the stu- never done this before. -

Population History in a Dangerous Environment: How Important May Natural Disasters Have Been?

POPULATION HISTORY IN A DANGEROUS ENVIRONMENT: HOW IMPORTANT MAY NATURAL DISASTERS HAVE BEEN? Anthony Reid Australian National University ABSTRACT KeywordsNatural disaster, VP INTRODUCTION Masyarakat Indonesia, Volume 39, No. 2, Desember 2013 | 505 00-MI-39,-No 2-2013.indd 505 4/10/2014 2:15:36 PM 506 | Masyarakat Indonesia, Volume 39, No. 2, Desember 2013 00-MI-39,-No 2-2013.indd 506 4/10/2014 2:15:36 PM Population History In A Dangerous Environment: ..... INDONESIA TAKES SHAPE IN A QUIET CENTURY 00-MI-39,-No 2-2013.indd 507 4/10/2014 2:15:36 PM 508 | Masyarakat Indonesia, Volume 39, No. 2, Desember 2013 Figure 1 Deaths in Indonesia from ‘natural’ (tectonic) disasters by century1 Map 1 00-MI-39,-No 2-2013.indd 508 4/10/2014 2:15:36 PM Population History In A Dangerous Environment: ..... | 509 Major natural threats to Southeast Asia 00-MI-39,-No 2-2013.indd 509 4/10/2014 2:15:36 PM 510 | Masyarakat Indonesia, Volume 39, No. 2, Desember 2013 2 ESTIMATING THE POPULATION EFFECTS OF MODERN ERUPTIONS 2 00-MI-39,-No 2-2013.indd 510 4/10/2014 2:15:36 PM Population History In A Dangerous Environment: ..... | 511 et al. 1998). -

06 9-9 TV Guide.Indd 1 9/9/08 7:48:19 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, September 9, 2008 Monday Evening September 15, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Batman Begins Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Christine CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late WEEK OF FRIDAY , SEPT . 12 THROUGH THUR S DAY , SEPT . 18 KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Toughest Jobs Dateline NBC Local Tonight Show Late FOX Sarah Connor Prison Break Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Intervention AMC Troy The Karate Kid ANIM Animal Cops Houston Animal Cops Houston Animal Precinct Miami Animal Police Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Dinos-Return Dino Mummy Into the Unknown How-Made How-Made Dinos-Return DISN Gotta Kick It Up Phineas Wizards Life With The Suite Montana So Raven Cory E! Ever After Dr. 90210 E! News Chelsea Chelsea The Soup ESPN Countdown NFL Football SportsCenter ESPN2 Poker Series of Poker Baseball Tonight E:60 NASCAR Now Norton TV FAM Holes Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club Whose? Whose? FX S.W.A.T. Changing Lanes '70s Show HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST Modern Marvels Journey to 10,000 BC Mega Disasters Modern Marvels LIFE Coco Chanel Will Will Frasier Frasier MTV Exiled Exiled Exiled The Hills The Hills Exiled The Hills Exiled Busted Busted NICK Familys SpongeBob Home Imp. -

Sunday Morning Grid 10/30/11 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

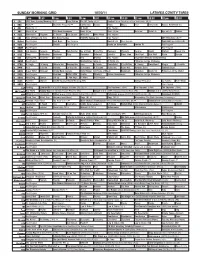

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/30/11 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face/Nation The NFL Today (N) Å Football Miami Dolphins at New York Giants. (N) Å 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference George House House Paid Travel Cafe Access Hollywood (N) 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week-Amanpour News (N) Å News (N) Å News Å Vista L.A. Eye on L.A. Motion 9 KCAL Tomorrow’s Kingdom K. Shook Joel Osteen Ministries Mike Webb Paid Program 11 FOX Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Paid Program UFC Primetime (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Best of L.A. Paid Program From Hell ›› (2001) (R) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program Hecho en Guatemala Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curiosity Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Paint This Dewberry Wyland’s Cuisine Cook’s Kitchen Sweet Life 28 KCET Cons. Wubbulous Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Lidsville Place, Own Chef Paul Burt Wolf Pépin Venetia 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Paid Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Muchachitas Como Tu Al Punto (N) Fútbol de la Liga Mexicana 40 KTBN K. Hagin Ed Young Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

1-3 Front-Area CFP 9-14-09.Indd 2 9/14/09 1:57:47 PM

Area/State Colby Free Press Monday, September 14, 2009 Page 3 Weather World’s Largest Convoy rolls into town Saturday Corner From “HOSTAGE,” Page 1 mart, a miniature Ford Mustang Mentlick drew the name of an auction to raise money for the American Legion Riders, Cran- replica, cups and hats. Mike Mense of Hoxie for a quilt Special Olympics. ston Trucking, Wilkens Truck and person in attendance, longest dis- Mentlick announced the winners made out of Special Olympics T- Committee member Jane Men- Trailer of Goodland, Mittens, Go- tance to get her, the trucker who for the best trucks after the door shirts from a jar. tlick said the convoy raised about etz Trucking of Park and Farmers traveled the longest distance and prizes had been handed out. His Once all the names had been $20,000. She said Tom and Lean- Oil Co. of Anthony. the company with the most trucks own truck was voted Best Paint, called and the awards handed out, na Sloan and Jack and Jan Collins She said 42 Special Olympi- at the convoy. a Cranston Trucking rig driven Mentlick announced the winners of Hoxie; Daryl and Cheryl Goetz ans attended this year, compared After the votes were handed in, by Robert Edwards won Best of the poster contest. The poster and daughter Michelle Goetz of to only 15 or 16 Olympians last committee chairman Joe Mentlick Chrome and George Winfield’s were collages the Special Olympi- Park; and Scott Carver helped put year. The Olympians came from pulled names out of a jar full of truck from Hill City was Best in ans drew to honor the truckers for together the event. -

On the Relativity of the Mental Health Consequences of Disasters

Michel L.A. Dückers On the relativity of the mental health consequences of disasters On the relativity of the mental health consequences of disasters This book is a publication of Arq Psychotrauma Expert Group and is part of the Arq book series. © 2019, M.L.A. Dückers All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the author. Cover: Stephan Csikós Cover image: Paul Klee betrofferer Ort, 1922, 109 Affected Place, 1922, 109 pen, pencil and watercolour on paper on cardboard 30,7 x 23,1 cm Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern Printing/binding: Gildeprint, Enschede ISBN: 978-94-632-3544-0 On the relativity of the mental health consequences of disasters Michel L.A. Dückers Foreword To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything and your heart will be wrung and possibly broken. If you want to make sure of keeping it intact you must give it to no one, not even an animal. Wrap it carefully round with hobbies and little luxuries; avoid all entanglements. Lock it up safe in the casket or coffin of your selfishness. But in that casket, safe, dark, motionless, airless, it will change. It will not be broken; it will become unbreakable, impenetrable, irredeemable. To love is to be vulnerable. C.S. Lewis – The Four Loves (1960) C.S. Lewis reminds us of how our vulnerability is linked to what matters most dearly to us. -

The Joint Return Period Analysis of Natural Disasters Based on Monitoring and Statistical Modeling of Multidimensional Hazard Factors

Science of the Total Environment 538 (2015) 724–732 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Science of the Total Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scitotenv The joint return period analysis of natural disasters based on monitoring and statistical modeling of multidimensional hazard factors Xueqin Liu a,b,c,NingLia,ShuaiYuanb,⁎,NingXub,WenqinShib, Weibin Chen b a State Key Laboratory of Earth Surface Processes and Resource Ecology, Beijing Normal University, Beijing 100875, China b National Marine Environmental Monitoring Center, State Oceanic Administration, Dalian 116023, China c School of Social Development and Public Policy, Beijing Normal University, Beijing 100875, China HIGHLIGHTS GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT • A method to estimate the multidimen- sional joint return periods is presented. • 2D function allows better fitting results at the lower tail of hazard factors. • Three-dimensional simulation has obvi- ous advantages in extreme value fitting. • Joint return periods are closer to the reality than univariate return periods. • Copula method provides a new idea for multivariate analysis of natural disasters. article info abstract Article history: As a random event, a natural disaster has the complex occurrence mechanism. The comprehensive analysis of Received 5 April 2015 multiple hazard factors is important in disaster risk assessment. In order to improve the accuracy of risk analysis Received in revised form 2 August 2015 and forecasting, the formation mechanism of a disaster should be considered in the analysis and calculation of Accepted 16 August 2015 multi-factors. Based on the consideration of the importance and deficiencies of multivariate analysis of dust Available online xxxx storm disasters, 91 severe dust storm disasters in Inner Mongolia from 1990 to 2013 were selected as study Editor: Simon Pollard cases in the paper. -

Introduction1

XV INTRODUCTION1 y most measures, 2012 was a ‘typical’ year for disasters. Worldwide, the number of disasters was, depending on which disaster database was consulted, either below or B above average, while economic damages were slightly below the ten-year average.2 In comparison with recent years, relatively few people died from disasters. There were no mega-disasters3 such as the 2010 earthquake in Haiti which left more than 200,000 dead or the 2010 floods in Pakistan which affected 20 million people, or the 2011 Japanese earthquake/tsunami/nuclear accident, where damages soared over $360 billion. The most serious disaster in terms of fatalities was Typhoon Bopha in the Philippines, where 1,100 people died in floods and landslides with hundreds still missing in early March. In the United States, Hurricane Sandy hit the industrial northeast, killing 131 people and causing between $20 and $50 billion in economic losses.4 The year also witnessed earthquakes (Iran, Philippines, Guatemala), floods (Pakistan, Russia, China, Bangladesh, India), cold waves (Europe, Peru), cyclones (Madagascar, Haiti) and drought (Sahel, US). But even in this ‘average’ year, there are lessons to be learned, particularly in the disquieting parallels between natural hazards occurring in 2011 and in 2012. In the US, Hurricane Sandy brought back memories of Hurricane Irene. Typhoon Bopha in the Philippines triggered comparisons to the 2011 Tropical Storm Washi. For Pakistan, 2012 was the third year in a row where millions were affected by floods. While weather-related natural hazards often occur in regular cycles (e.g. hurricane season in the Caribbean, monsoon season in South Asia, etc.) less is understood about the effects of recurrent disasters on community resilience and about the lessons which policy-makers draw from these experiences.