Recent Great Earthquakes and Tectonics in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kobe (Hyogo-Ken Nanbu), Japan, Earthquake of January 16, 1995

The Kobe (Hyogo-ken Nanbu), Japan, Earthquake of January 16, 1995 A report of preliminary observations prepared by Hiroo Kanamori California Institute of Technology he Kobe earthquake of January 16, 1995, is one of the Daishinsai (A major earthquake disaster in the Osaka-Kobe most damaging earthquakes in the recent history of area)." As ofJanuary 29, 1995, the casualty toll reached 5,094 T Japan. This earthquake is also called "The Hyogo-ken dead, 13 missing and 26,798 injured. Nanbu (Southern part of Hyogo prefecture) earthquake," This article presents some background on the earth- and the disaster caused by it is referred to as "Hanshin quake and its setting and a summary of some preliminary seismological results obtained by various investigators. The Japan Meteorological Agency ,/" e</-..... 0MA) located this earthquake at 34.60~ 135.00~ depth=22 km, origin time= 1943Tottori 1927Tango 1948 Fukui // '/~;/",~ 7 05:46:53.9, 1/17/1995JST, (20:46:53.9, 1/16/ (M=7.2) (M=7.a) (M=7.~) / ,.~o~.>:'/ k i 1995 GMT) with a JMA magnitude Mj=7.2 rS.. 7a (Figure 1). The epicenter is close to the city of Kobe (population, about 1.4 million), ap- proximately 200 km away from the Nankai trough (the major plate boundary between ,0., ~" "v"~.M "-'-" ~ the Philippine Sea and the Eurasia plates), and about 40 km from the Median Tectonic Line. In this sense this earthquake can be called an intraplate earthquake. In central- ,,o, oi ~J/ ,~ western Japan four major intraplate earth- .... "...C%<,,. ",z,.-.. :~/.S,,.-/" I \,q' _.. s , quakes have occurred since 1890 (Figure 1): . -

Large Intermediate-Depth Earthquakes and the Subduction Process

80 Physics ofthe Earth and Planetary Interiors, 53 (1988) 80—166 Elsevier Science Publishers By., Amsterdam — Printed in The Netherlands Large intermediate-depth earthquakes and the subduction process Luciana Astiz ~, Thorne Lay 2 and Hiroo Kanamori ~ ‘Seismological Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA (U.S.A.) 2 Department of Geological Sciences, University ofMichigan, Ann Arbor, MI (USA.) (Received September 22, 1987; accepted October 21, 1987) Astiz, L., Lay, T. and Kanamori, H., 1988. Large intermediate-depth earthquakes and the subduction process. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter., 53: 80—166. This study provides an overview of intermediate-depth earthquake phenomena, placing emphasis on the larger, tectonically significant events, and exploring the relation of intermediate-depth earthquakes to shallower seismicity. Especially, we examine whether intermediate-depth events reflect the state of interplate coupling at subduction zones. and whether this activity exhibits temporal changes associated with the occurrence of large underthrusting earthquakes. Historic record of large intraplate earthquakes (m B 7.0) in this century shows that the New Hebrides and Tonga subduction zones have the largest number of large intraplate events. Regions associated with bends in the subducted lithosphere also have many large events (e.g. Altiplano and New Ireland). We compiled a catalog of focal mechanisms for events that occurred between 1960 and 1984 with M> 6 and depth between 40 and 200 km. The final catalog includes 335 events with 47 new focal mechanisms, and is probably complete for earthquakes with mB 6.5. For events with M 6.5, nearly 48% of the events had no aftershocks and only 15% of the events had more than five aftershocks within one week of the mainshock. -

Coseismic Slip Model of Offshore Moderate Interplate Earthquakes on March 9, 2011 in Tohoku Using Tsunami Waveforms Tatsuya Kubo

1 Coseismic slip model of offshore moderate interplate earthquakes on March 9, 2 2011 in Tohoku using tsunami waveforms 3 Tatsuya Kubotaa*Ryota Hinoa, Daisuke Inazub1, Yoshihiro Itoc, Takeshi Iinumad, 4 Yusaku Ohtaa, Syuichi Suzukia, Kensuke Suzukid 5 a Graduate School of Science, Tohoku University, 6-6, Aza-Aoba, Aramaki, Aoba-ku, 6 Sendai 980-8578, Japan. 7 bU Tokyo Ocean Alliance, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan. 8 cDisaster Prevention Research Institute, Kyoto University, Uji, Japan. 9 dJapan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, Yokohama, Japan. 10 1Present address: Department of Ocean Sciences, Tokyo University of Marine Science 11 and Technology, Tokyo, Japan. 12 13 E-mail addresses: 14 Tatsuya Kubota: [email protected] 15 Ryota Hino: [email protected] 16 Daisuke Inazu: [email protected] 17 (Present e-mail address: [email protected]) 18 Yoshihiro Ito: [email protected] 19 Takeshi Iinuma: [email protected] 20 Yusaku Ohta: [email protected] 21 Syuichi Suzuki: [email protected] 22 Kensuke Suzuki: [email protected] 23 *Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] 1 24 25 Abstract 26 We estimated the coseismic slip distribution associated with the Mw 7.2 and 6.5 27 foreshocks of the 2011 Tohoku-Oki earthquake based on analysis of the tsunami 28 waveform records obtained just above their focal areas. The results show that the main 29 rupture areas of each of the foreshocks do not overlap with each other, and show a 30 distribution that is complementary to the postseismic slip area of the first Mw 7.2 31 foreshock as well as to the epicenters of smaller earthquakes during foreshock activity. -

Presence of Interplate Channel Layer Controls of Slip During and After The

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Presence of interplate channel layer controls of slip during and after the 2011 Tohoku‑Oki earthquake through the frictional characteristics Ryoko Nakata1*, Takane Hori2, Seiichi Miura3 & Ryota Hino1 There are signifcant diferences between the middle and southern segments of the Japan Trench in terms of the seismic and aseismic slips on the plate interface and seismic velocity structures. Although the large coseismic slip of the 2011 Tohoku‑Oki earthquake was limited to the middle segment, the observed negative residual gravity anomaly area in the southern segment corresponds to the postseismic slip area of the Tohoku‑Oki earthquake. A density distribution model can explain the diferent slip behaviours of the two segments by considering their structural diferences. The model indicates that the plate interface in the south was covered with a thick channel layer, as indicated by seismic survey imaging, and this layer resulted in a residual gravity anomaly. Numerical simulations which assumed evident frictional heterogeneity caused by the layer in the south efciently reproduced M9 earthquakes recurring only in the middle, followed by evident postseismic slips in the south. This study proposes that although the layer makes the megathrust less compliant to seismic slip, it promotes aseismic slips following the growth of seismic slips on the fault in an adjacent region. Many studies which investigated the spatiotemporal distributions of various seismic and geodetic events and underground structures have demonstrated that there are conspicuous diferences between the middle and southern segments of the Japan Trench. Te shallow area of the coast of Fukushima Prefecture, i.e. -

A Possible Restart of an Interplate Slow Slip Adjacent to the Tokai Seismic Gap in Japan Shinzaburo Ozawa*, Mikio Tobita and Hiroshi Yarai

Ozawa et al. Earth, Planets and Space (2016) 68:54 DOI 10.1186/s40623-016-0430-4 FULL PAPER Open Access A possible restart of an interplate slow slip adjacent to the Tokai seismic gap in Japan Shinzaburo Ozawa*, Mikio Tobita and Hiroshi Yarai Abstract The Tokai region of Japan is known to be a seismic gap area and is expected to be the source region of the antici- pated Tokai earthquake with a moment magnitude of over 8. Interplate slow slip occurred from approximately 2001 and subsided in 2005 in the area adjacent to the source region of the expected Tokai earthquake. Eight years later, the Tokai region again revealed signs of a slow slip from early 2013. This is the first evidence based on a dense Global Positioning System network that Tokai long-term slow slips repeatedly occur. Two datasets with different detrending produce similar transient crustal deformation and aseismic slip models, supporting the occurrence of the Tokai slow slip. The center of the current Tokai slow slip is near Lake Hamana, south of the center of the previous Tokai slow slip. The estimated moments, which increase at a roughly constant rate, amount to that of an earthquake with a moment magnitude of 6.6. If the ongoing Tokai slow slip subsides soon, it will suggest that there are at least two different types of slow slip events in the Tokai long-term slow slip area: that is, a large slow slip with a moment magnitude of over 7 with undulating time evolution and a small one with a moment magnitude of around 6.6 with a roughly linear time evolution. -

Crustal Faults in the Chilean Andes: Geological Constraints and Seismic Potential

Andean Geology 46 (1): 32-65. January, 2019 Andean Geology doi: 10.5027/andgeoV46n1-3067 www.andeangeology.cl Crustal faults in the Chilean Andes: geological constraints and seismic potential *Isabel Santibáñez1, José Cembrano2, Tiaren García-Pérez1, Carlos Costa3, Gonzalo Yáñez2, Carlos Marquardt4, Gloria Arancibia2, Gabriel González5 1 Programa de Doctorado en Ciencias de la Ingeniería, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Avda. Vicuña Mackenna 4860, Macul, Santiago, Chile. [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Departamento de Ingeniería Estructural y Geotécnica, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Avda. Vicuña Mackenna 4860, Macul, Santiago, Chile. [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] 3 Departamento de Geología, Universidad de San Luis, Ejercito de Los Andes 950, D5700HHW San Luis, Argentina. [email protected] 4 Departamento de Ingeniería Estructural y Geotécnica y Departamento de Ingeniería de Minería, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Avda. Vicuña Mackenna 4860, Macul, Santiago, Chile. [email protected] 5 Departamento de Ciencias Geológicas, Universidad Católica del Norte, Angamos 0610, Antofagasta, Chile. [email protected] * Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT. The Chilean Andes, as a characteristic tectonic and geomorphological region, is a perfect location to unravel the geologic nature of seismic hazards. The Chilean segment of the Nazca-South American subduction zone has experienced mega-earthquakes with Moment Magnitudes (Mw) >8.5 (e.g., Mw 9.5 Valdivia, 1960; Mw 8.8 Maule, 2010) and many large earthquakes with Mw >7.5, both with recurrence times of tens to hundreds of years. By contrast, crustal faults within the overriding South American plate commonly have longer recurrence times (thousands of years) and are known to produce earthquakes with maximum Mw of 7.0 to 7.5. -

Drilling Into Shallow Interplate Thrust Zone for Understanding of Irregular Rupturing of Megathrust

Drilling into shallow interplate thrust zone for understanding of irregular rupturing of megathrust Ryota Hino (Tohoku University) * abstract It is generally conceived that the shallowest portion of the megathrsut fault is completely aseismic and allow stable sliding during the interseismic period. However, anomalous tsunami earthquakes sporadically happen in this area, causing disproportionally large tsunami as compared to the radiated seismic energy, release large displacement at the plate boundary. It has not been well understood why and how such the anomalous earthquake occurs irregularly. Also in the rupture propagation of gigantic (M>9) earthquakes involving simultaneous rupturing of multiple asperities, the aseismic plate boundary seems to play an important role. Therefore, the mechanical properties of the most trenchward zone of the subudction plate boundary are very important for understanding mechanisms generating catastrophic earthquakes. I propose here to make long-term monitoring in deep boreholes drilled the shallowest portion of the megathrust fault to clarify how deform this area in the interseismic period. Downhole logging and seismic profiling will provide the answer to the cause of the anomalous rupture process by revealing the internal structure of the fault zone. * Research center for prediction of earthquakes and volcanic eruption Graduate School of Science, Tohoku University [email protected] 1. Introduction The occurrence of the 2004 Sumatra-Andaman earthquake (M9.1) showed that an interplate earthquake which ruptures almost entire part of a subduction system can occur, although we only know recurrence history of thrust earthquakes with sizes of M~8 in the system. Recent paleoseismological studies have revealed the occurrence of gigathrust earthquakes, much larger than M8 class megathrust earthquakes, in other subduction zones where only megathrust earthquakes have been known to occur. -

A Discussion on the Relations of Site Effect and Damage of Wooden Houses Using with Microtremors in Fukui Plain Affected by the 1948 Fukui Earthquake

13th World Conference on Earthquake Engineering Vancouver, B.C., Canada August 1-6, 2004 Paper No. 722 A DISCUSSION ON THE RELATIONS OF SITE EFFECT AND DAMAGE OF WOODEN HOUSES USING WITH MICROTREMORS IN FUKUI PLAIN AFFECTED BY THE 1948 FUKUI EARTHQUAKE. Norio ABEKI*1 and Toshiyuki MAEDA*2 SUMMARY Authors observed microtremors in Fukui Plain to discuss on the relationships between dynamic characteristics of surface geology and the damages of wooden houses caused by the 1948 Fukui Earthquake. By the distribution maps of predominant periods using H/V spectral ratio and damaged ratios of wooden houses, the distribution of the short periods corresponded to the low damaged ratios. And the areas of predominant long periods distributed on alluvial deposit in the western part from the earthquake fault. The high damage ratios at the sites of alluvial deposit are located within 8km from the earthquake fault, but the ratios decreased and varied widely in the areas farther than 8km. The predominant periods are related with the thickness of alluvial deposit. We can conclude that the earthquake damages were related with the dynamic characteristics of surface geology in this area. INTRODUCTION The 1948 Fukui Earthquake occurred at July 28, 1948 and it affected the buildings, railway, road, bridges and another social facilities. 3,763 persons had been killed, 36,134 houses completely and 11,816 houses partially destroyed, and 3,851 houses burned down by The Earthquake.1) The epicenter located at Maruoka town where is in the Fukui Plain, and the seismic fault went through from south to north in the plain. -

Repeated Occurrence of Surface-Sediment Remobilization

Ikehara et al. Earth, Planets and Space (2020) 72:114 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40623-020-01241-y FULL PAPER Open Access Repeated occurrence of surface-sediment remobilization along the landward slope of the Japan Trench by great earthquakes Ken Ikehara1* , Kazuko Usami1,2 and Toshiya Kanamatsu3 Abstract Deep-sea turbidites have been utilized to understand the history of past large earthquakes. Surface-sediment remo- bilization is considered to be a mechanism for the initiation of earthquake-induced turbidity currents, based on the studies on the event deposits formed by recent great earthquakes, such as the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake, although submarine slope failure has been considered to be a major contributor. However, it is still unclear that the surface-sed- iment remobilization has actually occurred in past great earthquakes. We examined a sediment core recovered from the mid-slope terrace (MST) along the Japan Trench to fnd evidence of past earthquake-induced surface-sediment remobilization. Coupled radiocarbon dates for turbidite and hemipelagic muds in the core show small age diferences (less than a few 100 years) and suggest that initiation of turbidity currents caused by the earthquake-induced surface- sediment remobilization has occurred repeatedly during the last 2300 years. On the other hand, two turbidites among the examined 11 turbidites show relatively large age diferences (~ 5000 years) that indicate the occurrence of large sea-foor disturbances such as submarine slope failures. The sedimentological (i.e., of diatomaceous nature and high sedimentation rates) and tectonic (i.e., continuous subsidence and isolated small basins) settings of the MST sedimentary basins provide favorable conditions for the repeated initiation of turbidity currents and for deposition and preservation of fne-grained turbidites. -

Overview and Recent Progress in Earthquake Prediction Research in Japan

Overview and Recent Progress in Earthquake Prediction Research in Japan Koshun YAMAOKA 山岡耕春 Graduate School of Environmental Studies Nagoya University 名古屋大学環境学研究科 地震火山・防災研究中心 contents Earthquake Prediction Research Systematization Historical overview of Japanese program Strategy in the new program of earthquake prediction research Noticeable results Published in May 2007 Systematization (1) Requirements in earthquake prediction WHEN (Time) WHERE (Place) HOW BIG (Magnitude) Earthquake prediction is to know these components with practical accuracy before an earthquake. Systematization(2) Classification of earthquake prediction in terms of time accuracy. Long-term prediction Statistical prediction using time history of earthquake occurrence. Mid-term prediction Computer simulation based on physical model using monitoring data. Short-term prediction Prediction using precursory phenomena of earthquakes. Present State of earthquake prediction (in Japan) Long-term Mid-term Short-term (tens to hundreds years) (years to months) (Days to hours) Almost established for Place inter-plate and active Same as left Same as left faults Almost established for Magnitude inter-plate and active Same as left Same as left faults Issued by the Under Under Time government development development National earthquake prediction program (Old program) 1965-1998 1. Establishment of nationwide observation network • Seismic observation network • Telemetry network • Deep borehole measurement in Tokyo metropolitan area • Strain observation network • Bury-in type volumetric strainmeters in Kanto-Tokai 2. Detection of precursors for long-term and short-term prediction of earthquakes • Seismic gap, for long-term precursor • Seismicity, crustal deformation etc… • Basic research Short-term precursors before 1978 Izu- Oshima Kinkai Earthquake. -One of the very few examples. From the Brochure of Earthquake prediction program (1991) New national program for earthquake prediction research 1. -

Rate/State Coulomb Stress Transfer Model for the CSEP Japan Seismicity Forecast

Earth Planets Space, 63, 171–185, 2011 Rate/state Coulomb stress transfer model for the CSEP Japan seismicity forecast Shinji Toda1 and Bogdan Enescu2 1Disaster Prevention Research Institute (DPRI), Kyoto University, Gokasho, Uji, Kyoto 611-0011, Japan 2National Research Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Prevention (NIED), 3-1 Tennodai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-0006, Japan (Received June 25, 2010; Revised January 13, 2011; Accepted January 13, 2011; Online published March 4, 2011) Numerous studies retrospectively found that seismicity rate jumps (drops) by coseismic Coulomb stress increase (decrease). The Collaboratory for the Study of Earthquake Prediction (CSEP) instead provides us an opportunity for prospective testing of the Coulomb hypothesis. Here we adapt our stress transfer model incorporating rate and state dependent friction law to the CSEP Japan seismicity forecast. We demonstrate how to compute the forecast rates of large shocks in 2009 using the large earthquakes during the past 120 years. The time dependent impact of the coseismic stress perturbations explains qualitatively well the occurrence of the recent moderate size shocks. Such ability is partly similar to that of statistical earthquake clustering models. However, our model differs from them as follows: the off-fault aftershock zones can be simulated using finite fault sources; the regional areal patterns of triggered seismicity are modified by the dominant mechanisms of the potential sources; the imparted stresses due to large earthquakes produce stress shadows that lead to a reduction of the forecasted number of earthquakes. Although the model relies on several unknown parameters, it is the first physics based model submitted to the CSEP Japan test center and has the potential to be tuned for short-term earthquake forecasts. -

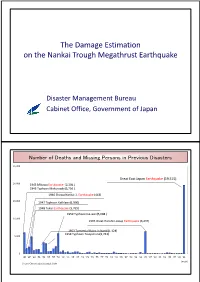

The Damage Estimation on the Nankai Trough Megathrust

The Damage Estimation onthen the Nankai Trough Megathrust Earthquake Disaster Management Bureau Cabinet Office, Government of Japan Number of Deaths and Missing Persons in Previous Disasters 25, 000 Great East Japan Earthquake (19,515) 20,000 1945 Mikawa Earthquake (2,306 ) 1945 Typhoon Makurazaki(3,756 ) 1946 Showa Nankai 1, Earthquake (443) 15,000 1947 Typhoon Kathleen(1,930) 1948 Fukui Earthquake (3,769) 1959 Typhoon Ise-wan(5,098 ) 10,000 1995 Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake (6,437) 1953 Torrential Rains in Nanki(1,124) 1954 Typhoon Touyamaru(1,761) 5,000 0 '45 '47 '49 '51 '53 '55 '57 '59 '61 '63 '65 '67 '69 '71 '73 '75 '77 '79 '81 '83 '85 '87 '89 '91 '93 '95 '97 '99 '01 '03 '05 '07 '09 '11 (year) Source: Chronological Scientific Table Large Earthquakes Reviewed by the Central Disaster Management Council Super wide-area earthquake extending to western Japan Tokikai Eart hqua ke Huge tsunami over 20 meters Tonankai, Nankai Earthquake Rate of earthquake production over 30 years: Oceanic-type earthquakes 60 ~ 70% in the vicinity of the Japan and Chishima Trenches Concerns about neglected timber buildings and Unknown ( Miyagi offshore cultural assets earthquake production rate over 30 years: 99% prior to the Great East Cyubu region, Kinki region Japan Earthquake) Inland Earthquake Concern about critical national operations Tokyyqo Inland Earthquake Rate of earthquake production over 30 years: approx 70% (Magnitude 7 in southern Kanto area) Oceanic earthquake Inland earthquake Rate of earthquake occurrence is by Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Planning and Review for Countermeasures Against Earthquakes (1) Estimate distribution of seismic intensity, tsunami height, etc.