May Pop - Part One

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0805 AARWBA.P65

ImPRESSions© The Official Newsletter Of The American Auto Racing Writers and Broadcasters Association August 2005 Vol. 38 No. 7 AARWBA Thanks Our Official 50th Anniversary Sponsors: (Click on any logo to go to that sponsor’s website!) 36th annual All-America Team Dinner, Saturday, Dec. 3, Hyatt Regency in downtown Indianapolis NASCAR President Helton to be Featured Speaker At All-America Team Dinner, Dec. 3, in Indianapolis NASCAR President Mike Helton will be the featured speaker at the AARWBA’s 36th annual All-America Team dinner, Saturday, Dec. 3, at the Hyatt Re- gency in downtown Indianapolis. The dinner will mark the official conclusion of AARWBA’s 50th Anniversary Celebration. Helton will share his important insights with AARWBA members and guests in Indy one day after the annual NASCAR NEXTEL Cup awards cer- emony in New York City. Helton has been a key 842-7005 leader in growing NASCAR into America’s No. 1 motorsports series and one of the country’s most popular mainstream sports attractions. Before becoming NASCAR president in late 2000, Helton had management positions at the Atlanta and Talladega tracks, and later was NASCAR’s vice president for competition and then senior VP and chief operating officer. “I’m happy to accept AARWBA’s invitation to speak at the All-America Team dinner,” said Helton. “AARWBA members have played an important role in the growth of NASCAR and motorsports in general. I look forward to this opportunity, and to join AARWBA in recognizing the champion drivers of 2005, and congratulating AARWBA on a successful 50th anniversary.” AARWBA members voted NASCAR’s founding France Family as Newsmaker of the Half-Cen- tury, the headline event of the 50th Anniversary Celebration. -

Road & Track Magazine Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8j38wwz No online items Guide to the Road & Track Magazine Records M1919 David Krah, Beaudry Allen, Kendra Tsai, Gurudarshan Khalsa Department of Special Collections and University Archives 2015 ; revised 2017 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Road & Track M1919 1 Magazine Records M1919 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Road & Track Magazine records creator: Road & Track magazine Identifier/Call Number: M1919 Physical Description: 485 Linear Feet(1162 containers) Date (inclusive): circa 1920-2012 Language of Material: The materials are primarily in English with small amounts of material in German, French and Italian and other languages. Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 36 hours in advance. Abstract: The records of Road & Track magazine consist primarily of subject files, arranged by make and model of vehicle, as well as material on performance and comparison testing and racing. Conditions Governing Use While Special Collections is the owner of the physical and digital items, permission to examine collection materials is not an authorization to publish. These materials are made available for use in research, teaching, and private study. Any transmission or reproduction beyond that allowed by fair use requires permission from the owners of rights, heir(s) or assigns. Preferred Citation [identification of item], Road & Track Magazine records (M1919). Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. Note that material must be requested at least 36 hours in advance of intended use. -

EVERY FRIDAY Vol. 17 No.1 the WORLD's FASTEST MO·TOR RACE Jim Rathmann (Zink Leader) Wins Monza 500 Miles Race at 166.73 M.P.H

1/6 EVERY FRIDAY Vol. 17 No.1 THE WORLD'S FASTEST MO·TOR RACE Jim Rathmann (Zink Leader) Wins Monza 500 Miles Race at 166.73 m.p.h. -New 4.2 Ferrari Takes Third Place-Moss's Gallant Effort with the Eldorado Maserati AT long last the honour of being the big-engined machines roaring past them new machines, a \'-12, 4.2-litre and a world's fastest motor race has been in close company, at speeds of up to 3-litre V-6, whilst the Eldorado ice-cream wrested from Avus, where, in prewar 190 m.p.h. Fangio had a very brief people had ordered a V-8 4.2-litre car days, Lang (Mercedes-Benz) won at an outing, when his Dean Van Lines Special from Officine Maserati for Stirling Moss average speed of 162.2 m.p.h. Jim Rath- was eliminated in the final heat with fuel to drive. This big white machine was mann, driving the Zink Leader Special, pump trouble after a couple of laps; soon known amongst the British con- made Monza the fastest-ever venue !by tingent as the Gelati-Maserati! Then of winning all three 63-1ap heats for the course there was the Lister-based, quasi- Monza 500 Miles Race, with an overall single-seater machine of Ecurie Ecosse. speed of 166.73 m.p.h. By Gregor Grant The European challenge was completed Into second place came the 1957 win- Photography by Publifoto, Milan by two sports Jaguars, and Harry Schell ner, Jim Bryan (Belond A.P. -

Übersicht Rennen WM Endstand Rennfahrer

Übersicht Rennen WM Endstand Rennfahrer Quelle www.f1-datenbank.de Formel 1 Rennjahr 1954 Rennkalender Nr. Datum Land Rennkurs 1 17.01.1954 Argentinien Buenos Aires 2 31.05.1954 USA Indianapolis 500 3 20.06.1954 Belgien Spa Francorchamps 4 04.07.1954 Frankreich Reims 5 17.07.1954 England Silverstone 6 01.08.1954 Deutschland Nürburgring 7 22.08.1954 Schweiz Bremgarten 8 05.09.1954 Italien Monza 9 24.10.1954 Spanien Pedralbes Punkteverteilung Punktevergabe : Platz 1 = 8 Punkte Platz 2 = 6 Punkte Platz 3 = 4 Punkte Platz 4 = 3 Punkte Platz 5 = 2 Punkte Schnellste Rennrunde = 1 Punkt Gewertet wurden die besten 5 Resultate von 9 Rennen . Renndistanz 500 KM oder maximal 3 Stunden Besonderheit Fahrerwechsel waren erlaubt. Die erzielten Punkte wurden in diesen Fällen aufgeteilt. Das Rennen von Indianapolis zählte mit zur Weltmeisterschaft, allerdings nahmen die europäischen Teams an dem Rennen nicht teil. Quelle www.f1-datenbank.de Formel 1 Rennjahr 1954 Saisonrennen 1 Datum 17.01.1954 Land Argentinien Rennkurs Buenos Aires Wertung Fahrer Rennteam Motorhersteller Reifenhersteller Sieger Fangio Maserati Maserati Pirelli Platz 2 Farina Ferrari Ferrari Pirelli Platz 3 González F. Ferrari Ferrari Pirelli Platz 4 Trintignant Ferrari Ferrari Pirelli Platz 5 Bayol Gordini Gordini Englebert Platz 6 Schell Maserati Maserati Pirelli Schnellste Rennrunde González F. Ferrari Ferrari Pirelli Startaufstellung Platz Fahrer Team Motor Zeit KM/H 1 Farina Ferrari Ferrari 1:44,800 134,382 2 González F. Ferrari Ferrari 1:44,900 134,254 3 Fangio Maserati Maserati -

1911: All 40 Starters

INDIANAPOLIS 500 – ROOKIES BY YEAR 1911: All 40 starters 1912: (8) Bert Dingley, Joe Horan, Johnny Jenkins, Billy Liesaw, Joe Matson, Len Ormsby, Eddie Rickenbacker, Len Zengel 1913: (10) George Clark, Robert Evans, Jules Goux, Albert Guyot, Willie Haupt, Don Herr, Joe Nikrent, Theodore Pilette, Vincenzo Trucco, Paul Zuccarelli 1914: (15) George Boillot, S.F. Brock, Billy Carlson, Billy Chandler, Jean Chassagne, Josef Christiaens, Earl Cooper, Arthur Duray, Ernst Friedrich, Ray Gilhooly, Charles Keene, Art Klein, George Mason, Barney Oldfield, Rene Thomas 1915: (13) Tom Alley, George Babcock, Louis Chevrolet, Joe Cooper, C.C. Cox, John DePalma, George Hill, Johnny Mais, Eddie O’Donnell, Tom Orr, Jean Porporato, Dario Resta, Noel Van Raalte 1916: (8) Wilbur D’Alene, Jules DeVigne, Aldo Franchi, Ora Haibe, Pete Henderson, Art Johnson, Dave Lewis, Tom Rooney 1919: (19) Paul Bablot, Andre Boillot, Joe Boyer, W.W. Brown, Gaston Chevrolet, Cliff Durant, Denny Hickey, Kurt Hitke, Ray Howard, Charles Kirkpatrick, Louis LeCocq, J.J. McCoy, Tommy Milton, Roscoe Sarles, Elmer Shannon, Arthur Thurman, Omar Toft, Ira Vail, Louis Wagner 1920: (4) John Boling, Bennett Hill, Jimmy Murphy, Joe Thomas 1921: (6) Riley Brett, Jules Ellingboe, Louis Fontaine, Percy Ford, Eddie Miller, C.W. Van Ranst 1922: (11) E.G. “Cannonball” Baker, L.L. Corum, Jack Curtner, Peter DePaolo, Leon Duray, Frank Elliott, I.P Fetterman, Harry Hartz, Douglas Hawkes, Glenn Howard, Jerry Wonderlich 1923: (10) Martin de Alzaga, Prince de Cystria, Pierre de Viscaya, Harlan Fengler, Christian Lautenschlager, Wade Morton, Raoul Riganti, Max Sailer, Christian Werner, Count Louis Zborowski 1924: (7) Ernie Ansterburg, Fred Comer, Fred Harder, Bill Hunt, Bob McDonogh, Alfred E. -

Harry A. Miller Club News

Winter Issue 2018 The Harry A. Miller Club Harry A. Miller Club News 1958 Indy 500 - George Amick behind the wheel. The Demler Special he Demler Special, a gorgeous front- 1958 figures out to be $187,000 in today’s Motor Speedway, Amick already had three T engine roadster with it’s Offenhauser money. Perhaps the powers-to-be on 16th & USAC National Championship car wins (All engine laid on its side, is an magnificent race Georgetown today need to look at that cost. three on dirt), under his belt (Langhorne & car and was a fan favorite at the Indianapolis In May of 1958, apple farmer Norm Demler Phoenix -1956 & Lakewood – 1957). Talented Speedway. Quin Epperly built the attractive who hailed from western New York-state hired mechanic Bob “Rocky” Phillipp worked out laydown roadster for $13,000 plus $9000 for “rookie,” George Amick to drive the new car. the bugs at the beginning of month, turning a fresh new Offenhauser. The price seems rea- Amick, loved fishing so had much he recently the car into a frontrunner as Amick drove the sonable, today that would buy you an entry- had moved to Rhinelander, WI to follow his it to a second place in the “500” its only race level sedan. The roadster costing $22,000 in hobby. Perhaps a rookie at the Indianapolis that year. The following year at Indianapolis 1 Winter Issue 2018 it was versatile Paul Goldsmith who teamed up with his buddy, Ray Nichels turning the wrenches. The underrated Goldsmith drove the car to another top-5 finish, once more the only appearance of the yellow No. -

Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated As of June 21, 2012 MAKE Manufacturer AC a C AMF a M F ABAR Abarth COBR AC Cobra SKMD Academy Mobile Homes (Mfd

Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated as of June 21, 2012 MAKE Manufacturer AC A C AMF A M F ABAR Abarth COBR AC Cobra SKMD Academy Mobile Homes (Mfd. by Skyline Motorized Div.) ACAD Acadian ACUR Acura ADET Adette AMIN ADVANCE MIXER ADVS ADVANCED VEHICLE SYSTEMS ADVE ADVENTURE WHEELS MOTOR HOME AERA Aerocar AETA Aeta DAFD AF ARIE Airel AIRO AIR-O MOTOR HOME AIRS AIRSTREAM, INC AJS AJS AJW AJW ALAS ALASKAN CAMPER ALEX Alexander-Reynolds Corp. ALFL ALFA LEISURE, INC ALFA Alfa Romero ALSE ALL SEASONS MOTOR HOME ALLS All State ALLA Allard ALLE ALLEGRO MOTOR HOME ALCI Allen Coachworks, Inc. ALNZ ALLIANZ SWEEPERS ALED Allied ALLL Allied Leisure, Inc. ALTK ALLIED TANK ALLF Allison's Fiberglass mfg., Inc. ALMA Alma ALOH ALOHA-TRAILER CO ALOU Alouette ALPH Alpha ALPI Alpine ALSP Alsport/ Steen ALTA Alta ALVI Alvis AMGN AM GENERAL CORP AMGN AM General Corp. AMBA Ambassador AMEN Amen AMCC AMERICAN CLIPPER CORP AMCR AMERICAN CRUISER MOTOR HOME Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated as of June 21, 2012 AEAG American Eagle AMEL AMERICAN ECONOMOBILE HILIF AMEV AMERICAN ELECTRIC VEHICLE LAFR AMERICAN LA FRANCE AMI American Microcar, Inc. AMER American Motors AMER AMERICAN MOTORS GENERAL BUS AMER AMERICAN MOTORS JEEP AMPT AMERICAN TRANSPORTATION AMRR AMERITRANS BY TMC GROUP, INC AMME Ammex AMPH Amphicar AMPT Amphicat AMTC AMTRAN CORP FANF ANC MOTOR HOME TRUCK ANGL Angel API API APOL APOLLO HOMES APRI APRILIA NEWM AR CORP. ARCA Arctic Cat ARGO Argonaut State Limousine ARGS ARGOSY TRAVEL TRAILER AGYL Argyle ARIT Arista ARIS ARISTOCRAT MOTOR HOME ARMR ARMOR MOBILE SYSTEMS, INC ARMS Armstrong Siddeley ARNO Arnolt-Bristol ARRO ARROW ARTI Artie ASA ASA ARSC Ascort ASHL Ashley ASPS Aspes ASVE Assembled Vehicle ASTO Aston Martin ASUN Asuna CAT CATERPILLAR TRACTOR CO ATK ATK America, Inc. -

Clean and Efficient Diesel Engines

2008 Diesel Engine-Efficiency and Emissions Research (DEER) Conference Clean & Efficient Diesel Engines - Designing for the Customer Dr Steve Charlton VP, Heavy-Duty Engineering Cummins Inc. Columbus, IN DEER Conference, August 5th 2008 “… so much has been written and said about the Diesel engine in recent months that it is hardly possible to say anything new” Diesel’s patent filed 1894 First successful operation 1897 Rudolf Diesel, c. 1910 Cummins founded 1919 DEER Conference, August 5th 2008 2 Diesel Race Cars – A Short (& Incomplete) History 1931 Cummins Diesel, Indy 500 1934 Cummins Diesel, Indy 500 1950 Cummins Diesel, Indy 500 1952 Cummins Diesel, Indy 500 2006 Audi Diesel, Le Mans 2007 Audi Diesel, Le Mans 2008 Audi & Peugeot Diesels, Le Mans DEER Conference, August 5th 2008 3 1931 Indy 500 Cummins Diesel, Driver Dave Evans Deusenberg Chassis, No Pit Stops ! 97 MPH Place 13th, Prize Money $450 1934 Indy 500 Cummins Diesel, Two-Stroke ! Driver Stubby Stubblefield Car Deusenberg, 105.9 MPH, 200 Laps Place 12th, Prize Money $880 1950 Indy 500 Winner, Driver Johnnie Parsons Car Kurtis-Kraft Offenhauser, 132 MPH Spun Magneto Stalled Piston Vibration Crankshaft Rod Overheating Rod Ignition Accident Magneto Crankshaft Oil line Drive gears Rear axle Clutch Oil tank Axle Drive shaft 1950 Indy 500 Cummins Diesel, Driver Jimmy JacksonClutch shaft Piston Car Kurtis-Kraft, Laps 52 of 138 / SuperchargerCaught fire Fuel tank 129.2 MPH Drive shaft Place 29th, Prize Money $1939 1952 Indianapolis 500 Pole Cummins Diesel Special Driver Freddie Agabashian, -

One Lap Record

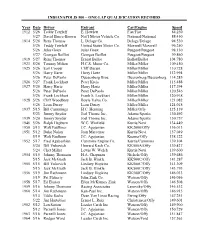

INDIANAPOLIS 500 – ONE-LAP QUALIFICATION RECORDS Year Date Driver Entrant Car/Engine Speed 1912 5/26 Teddy Tetzlaff E. Hewlett Fiat/Fiat 84.250 5/27 David Bruce-Brown Nat’l Motor Vehicle Co. National/National 88.450 1914 5/26 Rene Thomas L. Delage Co. Delage/Delage 94.530 5/26 Teddy Tetzlaff United States Motor Co. Maxwell/Maxwell 96.250 5/26 Jules Goux Jules Goux Peugeot/Peugeot 98.130 5/27 Georges Boillot Georges Boillot Peugeot/Peugeot 99.860 1919 5/27 Rene Thomas Ernest Ballot Ballot/Ballot 104.780 1923 5/26 Tommy Milton H.C.S. Motor Co. Miller/Miller 109.450 1925 5/26 Earl Cooper Cliff Durant Miller/Miller 110.728 5/26 Harry Hartz Harry Hartz Miller/Miller 112.994 5/26 Peter DePaolo Duesenberg Bros. Duesenberg/Duesenberg 114.285 1926 5/27 Frank Lockhart Peter Kreis Miller/Miller 115.488 1927 5/26 Harry Hartz Harry Hartz Miller/Miller 117.294 5/26 Peter DePaolo Peter DePaolo Miller/Miller 120.546 5/26 Frank Lockhart Frank S. Lockhart Miller/Miller 120.918 1928 5/26 Cliff Woodbury Boyle Valve Co. Miller/Miller 121.082 5/26 Leon Duray Leon Duray Miller/Miller 124.018 1937 5/15 Bill Cummings H.C. Henning Miller/Offy 125.139 5/23 Jimmy Snyder Joel Thorne Inc. Adams/Sparks 130.492 1939 5/20 Jimmy Snyder Joel Thorne Inc. Adams/Sparks 130.757 1946 5/26 Ralph Hepburn W.C. Winfield Kurtis/Novi 134.449 1950 5/13 Walt Faulkner J.C. Agajanian KK2000/Offy 136.013 1951 5/12 Duke Nalon Jean Marcenac Kurtis/Novi 137.049 5/19 Walt Faulkner J.C. -

Racing, Region, and the Environment: a History of American Motorsports

RACING, REGION, AND THE ENVIRONMENT: A HISTORY OF AMERICAN MOTORSPORTS By DANIEL J. SIMONE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2009 1 © 2009 Daniel J. Simone 2 To Michael and Tessa 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A driver fails without the support of a solid team, and I thank my friends, who supported me lap-after-lap. I learned a great deal from my advisor Jack Davis, who when he was not providing helpful feedback on my work, was always willing to toss the baseball around in the park. I must also thank committee members Sean Adams, Betty Smocovitis, Stephen Perz, Paul Ortiz, and Richard Crepeau as well as University of Florida faculty members Michael Bowen, Juliana Barr, Stephen Noll, Joseph Spillane, and Bill Link. I respect them very much and enjoyed working with them during my time in Gainesville. I also owe many thanks to Dr. Julian Pleasants, Director Emeritus of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program, and I could not have finished my project without the encouragement provided by Roberta Peacock. I also thank the staff of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program. Finally, I will always be grateful for the support of David Danbom, Claire Strom, Jim Norris, Mark Harvey, and Larry Peterson, my former mentors at North Dakota State University. A call must go out to Tom Schmeh at the National Sprint Car Hall of Fame, Suzanne Wise at the Appalachian State University Stock Car Collection, Mark Steigerwald and Bill Green at the International Motor Racing Resource Center in Watkins Glen, New York, and Joanna Schroeder at the (former) Ethanol Promotion and Information Council (EPIC). -

In Jjkt 49” 54” |

•• C-2 THE EVENING STAR, Washington, D. C. settled weather, believe WEDNESDAY, MAY 3#, 1936 I we that BASEBALL RESULTS crabbing and fishing will fall Nine-Horse Field Adios Harry into the usual pattern and pro- TO DECIDE SITE OF ' duce a lot more sport. in *** * TWIN CITIES FIGHT If you enjoy shotgun shooting, jjKt OUTDOORS by May all means set.aside this week In Dixie Headed ST. PAUL, Minn., 30 Is Favorite for Jgk, . • to (A5 ). Deadlocked boxing With BILL LEETCH end witness the 20th North- promoters in Minneapolis South shoot at the grounds of and St Paul came up today the National Capital Skeet and By with an unusual for Trap Club Friday and Saturday. Blue Choir solution Triple I Crown This is one of the most colorful ¦ I the location of a fight in- We’re just back from a trout occasion, writes By JOSEPH B. KELLY volving Harry, who t also to say the of all the great national shoot- a pair of middle- Adios set a world’s fishing expedition to Pennsyl- terrible, Star Racing Editor for 11/16 1 ¦ weather has been with ing events, and many of this weight rivals. They decided record miles last week vania. where put in fine mostly high BALTIMORE. May 30—One at Rosecroft, gets another we a ; winds, but that country’s finest shotgun artists to let the outcome of today’s shot day in pursuit of there plenty of the best turf races yet pre- at the mile mark tonight at the native brown i seem to be of will compete. -

Indianapolis 500 – Pace Cars

INDIANAPOLIS 500 – PACE CARS Year Pace Car Driver 1911 Stoddard-Dayton Carl G. Fisher 1912 Stutz Carl G. Fisher 1913 Stoddard-Dayton Carl G. Fisher 1914 Stoddard-Dayton Carl G. Fisher 1915 Packard “6” Carl G. Fisher 1916 Premier “6” Frank E. Smith 1919 Packard V-12 (called Twin Six) Col. J. G. Vincent 1920 Marmon “6” (Model 34) Barney Oldfield 1921 H.C.S. “6” Harry C. Stutz 1922 National Sextet Barney Oldfield 1923 Duesenberg Fred S. Duesenberg 1924 Cole V-8 Lew Pettijohn 1925 Rickenbacker “8” Eddie Rickenbacker 1926 Chrysler Imperial 80 Louis Chevrolet 1927 LaSalle V-8 “Big Boy” Rader 1928 Marmon “8” (Model 78) Joe Dawson 1929 Studebaker President George Hunt 1930 Cord L-29 Wade Morton 1931 Cadillac “Big Boy” Rader 1932 Lincoln Edsel Ford 1933 Chrysler Imperial (Phaeton) Byron Foy 1934 LaSalle “Big Boy” Rader 1935 Ford V-8 Harry Mack 1936 Packard 120 Tommy Milton 1937 LaSalle Series 50 Ralph DePalma 1938 Hudson 112 Stuart Baits 1939 Buick Roadmaster Charles Chayne 1940 Studebaker Harry Hartz 1941 Chrysler-Newport (Phaeton) A.B. Couture 1946 Lincoln V-12 Henry Ford II 1947 Nash Ambassador George W. Mason 1948 Chevrolet Fleetmaster Wilbur Shaw 1949 Oldsmobile 88 Wilbur Shaw 1950 Mercury Benson Ford 1951 Chrysler New Yorker V-8 Dave Wallace 1952 Studebaker Commander P.O. Peterson 1953 Ford Crestline Sunliner William C. Ford 1954 Dodge Royal William C. Newburg 1955 Chevrolet Bel Air T.H. Keating 1956 DeSoto Adventurer L.I. Woolson 1957 Mercury Convertible Cruiser F.C. Reith 1958 Pontiac Bonneville Sam Hanks 1959 Buick Electra 225 Sam Hanks 1960 Oldsmobile 98 Sam Hanks 1961 Ford Thunderbird Sam Hanks 1962 Studebaker Lark Sam Hanks 1963 Chrysler 300 Sam Hanks 1964 Ford Mustang Benson Ford 1965 Plymouth Sports Fury P.M.