Reclaiming the Ungentlemanly Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scissors Force (1940)

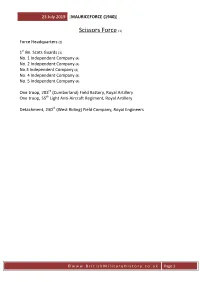

23 July 2019 [MAURICEFORCE (1940)] Scissors Force (1) Force Headquarters (2) st 1 Bn. Scots Guards (3) No. 1 Independent Company (4) No. 2 Independent Company (4) No.3 Independent Company (4) No. 4 Independent Company (4) No. 5 Independent Company (4) One troop, 203rd (Cumberland) Field Battery, Royal Artillery One troop, 55th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery Detachment, 230th (West Riding) Field Company, Royal Engineers ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Page 1 23 July 2019 [MAURICEFORCE (1940)] NOTES: 1. Scissors Force was formed in early May 1940 under the command of Colonel Colin McVean GUBBINS. The role of this force was to form a base in the Bodo, Mo and Mosjoen area to the south of Narvik and to block and delay the German advance from the south. 2. The Force Headquarters was formed from the staff of the 61st Infantry Division on 15 April 1940. 3. The 1st Bn. Scots Guards was part of the 24th Infantry Brigade (Guards) which was sent to assist in blocking the road at Mo. 4. These companies were formed with volunteers from the Territorial Army divisions then stationed in the United Kingdom. They were: Ø No. 1 Independent Company – Formed by the 52nd (Lowland) Division; Ø No. 2 Independent Company – Formed by the 53rd (Welsh) Division; Ø No. 3 Independent Company – Formed by the 54th (East Anglian) Division; Ø No. 4 Independent Company – Formed by the 55th (West Lancashire) Division; Ø No. 5 Independent Company – Formed by the 56th (London) Division; Each company comprised five officers and about two-hundred and seventy men organised into three platoons, each consisting of three sections. -

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Commemorating the Overseas-Born Victoria Cross Heroes a First World War Centenary Event

Commemorating the overseas-born Victoria Cross heroes A First World War Centenary event National Memorial Arboretum 5 March 2015 Foreword Foreword The Prime Minister, David Cameron The First World War saw unprecedented sacrifice that changed – and claimed – the lives of millions of people. Even during the darkest of days, Britain was not alone. Our soldiers stood shoulder-to-shoulder with allies from around the Commonwealth and beyond. Today’s event marks the extraordinary sacrifices made by 145 soldiers from around the globe who received the Victoria Cross in recognition of their remarkable valour and devotion to duty fighting with the British forces. These soldiers came from every corner of the globe and all walks of life but were bound together by their courage and determination. The laying of these memorial stones at the National Memorial Arboretum will create a lasting, peaceful and moving monument to these men, who were united in their valiant fight for liberty and civilization. Their sacrifice shall never be forgotten. Foreword Foreword Communities Secretary, Eric Pickles The Centenary of the First World War allows us an opportunity to reflect on and remember a generation which sacrificed so much. Men and boys went off to war for Britain and in every town and village across our country cenotaphs are testimony to the heavy price that so many paid for the freedoms we enjoy today. And Britain did not stand alone, millions came forward to be counted and volunteered from countries around the globe, some of which now make up the Commonwealth. These men fought for a country and a society which spanned continents and places that in many ways could not have been more different. -

Inscribed 6 (2).Pdf

Inscribed6 CONTENTS 1 1. AVIATION 33 2. MILITARY 59 3. NAVAL 67 4. ROYALTY, POLITICIANS, AND OTHER PUBLIC FIGURES 180 5. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 195 6. HIGH LATITUDES, INCLUDING THE POLES 206 7. MOUNTAINEERING 211 8. SPACE EXPLORATION 214 9. GENERAL TRAVEL SECTION 1. AVIATION including books from the libraries of Douglas Bader and “Laddie” Lucas. 1. [AITKEN (Group Captain Sir Max)]. LARIOS (Captain José, Duke of Lerma). Combat over Spain. Memoirs of a Nationalist Fighter Pilot 1936–1939. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. 8vo., cloth, pictorial dust jacket. London, Neville Spearman. nd (1966). £80 A presentation copy, inscribed on the half title page ‘To Group Captain Sir Max AitkenDFC. DSO. Let us pray that the high ideals we fought for, with such fervent enthusiasm and sacrifice, may never be allowed to perish or be forgotten. With my warmest regards. Pepito Lerma. May 1968’. From the dust jacket: ‘“Combat over Spain” is one of the few first-hand accounts of the Spanish Civil War, and is the only one published in England to be written from the Nationalist point of view’. Lerma was a bomber and fighter pilot for the duration of the war, flying 278 missions. Aitken, the son of Lord Beaverbrook, joined the RAFVR in 1935, and flew Blenheims and Hurricanes, shooting down 14 enemy aircraft. Dust jacket just creased at the head and tail of the spine. A formidable Vic formation – Bader, Deere, Malan. 2. [BADER (Group Captain Douglas)]. DEERE (Group Captain Alan C.) DOWDING Air Chief Marshal, Lord), foreword. Nine Lives. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. -

British Clandestine Activities in Romania During the Second World

British Clandestine Activities in Romania during the Second World War This page intentionally left blank British Clandestine Activities in Romania during the Second World War Dennis Deletant Visiting ‘Ion Ra¸tiu’ Professor of Romanian Studies, Georgetown University, USA © Dennis Deletant 2016 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2016 978–1–137–57451–0 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2016 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. -

Special Operations Executive - Wikipedia

12/23/2018 Special Operations Executive - Wikipedia Special Operations Executive The Special Operations Executive (SOE) was a British World War II Special Operations Executive organisation. It was officially formed on 22 July 1940 under Minister of Economic Warfare Hugh Dalton, from the amalgamation of three existing Active 22 July 1940 – 15 secret organisations. Its purpose was to conduct espionage, sabotage and January 1946 reconnaissance in occupied Europe (and later, also in occupied Southeast Asia) Country United against the Axis powers, and to aid local resistance movements. Kingdom Allegiance Allies One of the organisations from which SOE was created was also involved in the formation of the Auxiliary Units, a top secret "stay-behind" resistance Role Espionage; organisation, which would have been activated in the event of a German irregular warfare invasion of Britain. (especially sabotage and Few people were aware of SOE's existence. Those who were part of it or liaised raiding operations); with it are sometimes referred to as the "Baker Street Irregulars", after the special location of its London headquarters. It was also known as "Churchill's Secret reconnaissance. Army" or the "Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare". Its various branches, and Size Approximately sometimes the organisation as a whole, were concealed for security purposes 13,000 behind names such as the "Joint Technical Board" or the "Inter-Service Nickname(s) The Baker Street Research Bureau", or fictitious branches of the Air Ministry, Admiralty or War Irregulars Office. Churchill's Secret SOE operated in all territories occupied or attacked by the Axis forces, except Army where demarcation lines were agreed with Britain's principal Allies (the United Ministry of States and the Soviet Union). -

Political Visions and Historical Scores

Founded in 1944, the Institute for Western Affairs is an interdis- Political visions ciplinary research centre carrying out research in history, political and historical scores science, sociology, and economics. The Institute’s projects are typi- cally related to German studies and international relations, focusing Political transformations on Polish-German and European issues and transatlantic relations. in the European Union by 2025 The Institute’s history and achievements make it one of the most German response to reform important Polish research institution well-known internationally. in the euro area Since the 1990s, the watchwords of research have been Poland– Ger- many – Europe and the main themes are: Crisis or a search for a new formula • political, social, economic and cultural changes in Germany; for the Humboldtian university • international role of the Federal Republic of Germany; The end of the Great War and Stanisław • past, present, and future of Polish-German relations; Hubert’s concept of postliminum • EU international relations (including transatlantic cooperation); American press reports on anti-Jewish • security policy; incidents in reborn Poland • borderlands: social, political and economic issues. The Institute’s research is both interdisciplinary and multidimension- Anthony J. Drexel Biddle on Poland’s al. Its multidimensionality can be seen in published papers and books situation in 1937-1939 on history, analyses of contemporary events, comparative studies, Memoirs Nasza Podróż (Our Journey) and the use of theoretical models to verify research results. by Ewelina Zaleska On the dispute over the status The Institute houses and participates in international research of the camp in occupied Konstantynów projects, symposia and conferences exploring key European questions and cooperates with many universities and academic research centres. -

Hans Kammler, Hitler's Last Hope, in American Hands

WORKING PAPER 91 Hans Kammler, Hitler’s Last Hope, in American Hands By Frank Döbert and Rainer Karlsch, August 2019 THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES Christian F. Ostermann and Charles Kraus, Series Editors This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources from all sides of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. Among the activities undertaken by the Project to promote this aim are the Wilson Center's Digital Archive; a periodic Bulletin and other publications to disseminate new findings, views, and activities pertaining to Cold War history; a fellowship program for historians to conduct archival research and study Cold War history in the United States; and international scholarly meetings, conferences, and seminars. The CWIHP Working Paper series provides a speedy publication outlet for researchers who have gained access to newly-available archives and sources related to Cold War history and would like to share their results and analysis with a broad audience of academics, journalists, policymakers, and students. CWIHP especially welcomes submissions which use archival sources from outside of the United States; offer novel interpretations of well-known episodes in Cold War history; explore understudied events, issues, and personalities important to the Cold War; or improve understanding of the Cold War’s legacies and political relevance in the present day. -

0714685003.Pdf

CONTENTS Foreword xi Acknowledgements xiv Acronyms xviii Introduction 1 1 A terrorist attack in Italy 3 2 A scandal shocks Western Europe 15 3 The silence of NATO, CIA and MI6 25 4 The secret war in Great Britain 38 5 The secret war in the United States 51 6 The secret war in Italy 63 7 The secret war in France 84 8 The secret war in Spain 103 9 The secret war in Portugal 114 10 The secret war in Belgium 125 11 The secret war in the Netherlands 148 12 The secret war in Luxemburg 165 ix 13 The secret war in Denmark 168 14 The secret war in Norway 176 15 The secret war in Germany 189 16 The secret war in Greece 212 17 The secret war in Turkey 224 Conclusion 245 Chronology 250 Notes 259 Select bibliography 301 Index 303 x FOREWORD At the height of the Cold War there was effectively a front line in Europe. Winston Churchill once called it the Iron Curtain and said it ran from Szczecin on the Baltic Sea to Trieste on the Adriatic Sea. Both sides deployed military power along this line in the expectation of a major combat. The Western European powers created the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) precisely to fight that expected war but the strength they could marshal remained limited. The Soviet Union, and after the mid-1950s the Soviet Bloc, consistently had greater numbers of troops, tanks, planes, guns, and other equipment. This is not the place to pull apart analyses of the military balance, to dissect issues of quantitative versus qualitative, or rigid versus flexible tactics. -

Jataka Tales: Layers of Meaning from the Universal to the Personal

Jataka Tales: Layers of Meaning from the Universal to the Personal Grade Level or Course Type: English, Social Studies, adaptable for grades 6 through 10 Overview of the Lesson Jataka Tales: Birth Stories of the Buddha are among the world’s oldest collection of stories. Many, about endearing animals who misbehave – and then learn to behave better – are appealing to children throughout the world. In this lesson students compare an Aesop’s fable to a Jataka Tale to see what they share in common. Students then learn about the Buddhist context of the tales, through which they deepen their appreciation of what makes a Jataka Tale unique. Finally, students approach a Jataka Tale through the meaning it held in the life of Noor Inayat Khan (1914-1944), whose classic collection Twenty Jataka Tales is still in print. She was a Muslim who worked as a covert agent for the British in Occupied France. She died at Dachau in 1944. In all three activities, students gain insight into what makes stories important in our lives. Learning Outcomes: • Identify stories by genre as fable, parable, folktale and fairy tale. • Decipher the moral of a story. • Understand Buddhist concepts (Ten Perfections, cycle of death and rebirth) • Learn about the life and appreciate the artistry of Noor Inayat Khan. Materials Needed • This lesson and the handouts included with it. They include: Handout 1. Life of Noor Inayat Khan with photos and scrapbook activity Handout 2. The Monkey and the Dolphin credited to Aesop and genre definitions Handout 3. The Patient Buffalo, a Jataka Tale Handout 4. -

“A Licenced Troubleshooter” James Bond As Assassin

“A Licenced Troubleshooter” James Bond as Assassin ROGER PAULY If a pollster were to ask the average person on the street “What does James Bond do?” the response would almost certainly be that he is a spy. his is the most ba! sic defnition of the dashing British literary and "lm hero. But is it accurate? #o Bond$s activities represent spying or something else? %ecent studies have borne fruit by looking at the character of Bond outside of the basic parameters of the “spy” persona. &or example, )atharina *agen +,-./0 analysed Bond as a pirate; while #avid 2egram +,-./0 viewed him through the lens of an extreme athlete. 3f particular interest to this essay is Mathew edesco$s observation5 “6t7here$s no getting around it 8 James Bond is an assassin” +,--9( .,-0. edesco does not e'! plore this point in depth however( since his study is primarily devoted to the moral ethics of killing and torture. &urthermore, his characterisation of James Bond as an assassin is a decided anomaly in Bond scholarship and the spy classi! "cation remains predominant. &or example, Liisa &unnell and )laus #odds refer to Bond as a “British super spy” in a recent work +,-.;( ,.<0. his article will de! velop more fully edesco$s brief identi"cation by directly exploring the historical roots of Bond as an assassin. argeting key individuals for murder is an ancient and well-established el! ement of political and military history( and the Second World War was no e'cep! tion. In his capacity as an intelligence ofcer( Ian &leming had knowledge of ?l! Roger Pauly is /n Asso0i/*e Pro1essor o1 2is*or3 /* *he Uni5ersi*3 o1 ,en*r/l Ar6/ns/s% 2e is mos*ly 6nown 1or his 7or6 on *he his*or3 o1 1ire/rms bu* 4/s /lso wri**en on su('ec*s /s di5erse /s 8/r0us G/r5e39 8/u 8/u9 /n+ Mi- ami Vice% Volume 4 · Issue 1 · Spring 2021 ISSN 2514 21!" DOI$ 10%24"!!&'bs%)" Dis*ribu*ed under ,, -Y 4%0 U. -

Why UW: Factoring in the Decision Point for Unconventional Warfare

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2012-12 Why UW: factoring in the decision point for unconventional warfare Agee, Ryan C. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/27781 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS WHY UW: FACTORING IN THE DECISION POINT FOR UNCONVENTIONAL WARFARE by Ryan C. Agee Maurice K. DuClos December 2012 Thesis Advisor: Leo Blanken Second Reader: Doowan Lee Third Reader: Randy Burkett Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704–0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202–4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704–0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED December 2012 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS WHY UW: FACTORING IN THE DECISION POINT FOR UNCONVENTIONAL WARFARE 6. AUTHOR(S) Ryan C. Agee, Maurice K. DuClos 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School REPORT NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943–5000 9. SPONSORING /MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10.