250AB Mphil Final.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Seattle Foundation Annual Report Donors & Contributors 3

2008 The Seattle Foundation Annual Report Donors & Contributors 3 Grantees 13 Fiscal Sponsorships 28 Financial Highlights 30 Trustees and Staff 33 Committees 34 www.seattlefoundation.org | (206) 622-2294 While the 2008 financial crisis created greater needs in our community, it also gave us reason for hope. 2008 Foundation donors have risen to the challenges that face King County today by generously supporting the organizations effectively working to improve the well-being of our community. The Seattle Foundation’s commitment to building a healthy community for all King County residents remains as strong as ever. In 2008, with our donors, we granted more than $63 million to over 2000 organizations and promising initiatives in King County and beyond. Though our assets declined like most investments nationwide, The Seattle Foundation’s portfolio performed well when benchmarked against comparable endowments. In the longer term, The Seattle Foundation has outperformed portfolios comprised of traditional stocks and bonds due to prudent and responsible stewardship of charitable funds that has been the basis of our investment strategy for decades. The Seattle Foundation is also leading efforts to respond to increasing need in our community. Late last year The Seattle Foundation joined forces with the United Way of King County and other local funders to create the Building Resilience Fund—a three-year, $6 million effort to help local people who have been hardest hit by the economic downturn. Through this fund, we are bolstering the capacity of selected nonprofits to meet increasing basic needs and providing a network of services to put people on the road on self-reliance. -

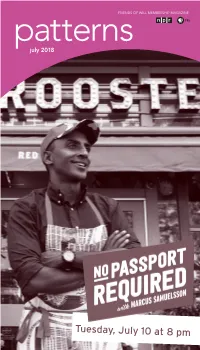

PDF Version of July 2018 Patterns

FRIENDS OF WILL MEMBERSHIP MAGAZINE patterns july 2018 Tuesday, July 10 at 8 pm WILL-TV TM patterns Membership Hotline: 800-898-1065 july 2018 Volume XLVI, Number 1 WILL AM-FM-TV: 217-333-7300 Campbell Hall 300 N. Goodwin Ave., Urbana, IL 61801-2316 Mailing List Exchange Donor records are proprietary and confidential. WILL does not sell, rent or trade its donor lists. Patterns Friends of WILL Membership Magazine Editor/Art Designer: Sarah Whittington Printed by Premier Print Group. Printed with SOY INK on RECYCLED, TM Trademark American Soybean Assoc. RECYCLABLE paper. Radio 90.9 FM: A mix of classical music and NPR information programs, including local news. (Also heard at 106.5 in Danville and with live streaming on will.illinois.edu.) See pages 4-5. 101.1 FM and 90.9 FM HD2: Locally produced music programs and classical music from C24. (101.1 The month of July means we’ve moved into a is available in the Champaign-Urbana area.) See page 6. new fiscal year here at Illinois Public Media. 580 AM: News and information, NPR, BBC, news, agriculture, talk shows. (Also heard on 90.9 FM HD3 First and foremost, I want to give a big thank with live streaming on will.illinois.edu.) See page 7. you to everyone who renewed or increased your gift to Illinois Public Media over the last Television 12 months. You continue to show your love and WILL-HD All your favorite PBS and local programming, in high support for what we do time and again. I am definition when available. -

The Buffalo Soldiers Study, March 2019

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUFFALO SOLDIERS STUDY MARCH 2019 BUFFALO SOLDIERS STUDY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION The study explores the Buffalo Soldiers’ stewardship role in the early years of the national Legislation and Purpose park system and identifies NPS sites associated with the history of the Buffalo Soldiers and their The National Defense Authorization Act of 2015, post-Civil War military service. In this study, Public Law 113-291, authorized the Secretary of the term “stewardship” is defined as the total the Interior to conduct a study to examine: management of the parks that the US Army carried out, including the Buffalo Soldiers. “The role of the Buffalo Soldiers in the early Stewardship tasks comprised constructing and years of the national park system, including developing park features such as access roads an evaluation of appropriate ways to enhance and trails; performing regular maintenance historical research, education, interpretation, functions; undertaking law enforcement within and public awareness of the Buffalo Soldiers in park boundaries; and completing associated the national parks, including ways to link the administrative tasks, among other duties. To a story to the development of national parks and lesser extent, the study also identifies sites not African American military service following the managed by the National Park Service but still Civil War.” associated with the service of the Buffalo Soldiers. The geographic scope of the study is nationwide. To meet this purpose, the goals of this study are to • evaluate ways to increase public awareness Study Process and understanding of Buffalo Soldiers in the early history of the National Park Service; and The process of developing this study involved five phases, with each phase building on and refining • evaluate ways to enhance historical research, suggestions developed during the previous phase. -

Discovery Park: a People’S Park in Magnolia

Discovery Park: A People’s Park In Magnolia By Bob Kildall Memorial to US District Judge Donald S. Voorhees Authors Note: Before Don died he asked me to say a few words at his memorial service about Discovery Park. After his death July 7, 1989, Anne Voorhees asked me to help in a different capacity. This is the speech I wrote and later used at a Friends of Discovery Park memorial service and in a letter to the editor. Discovery Park is his park—that we all agree. He felt that Seattle would be known for this Park—like London is known for Hyde Park; Vancouver for Stanley Park; San Francisco for Golden Gate Park and New York for Central Park. It was a difficult task. The Department of Defense wanted an anti-ballistic missile base and the ABM headquarters for the entire West Coast located here. Native Americans claimed the property. We didn’t have enough money to buy the land and no federal law allowed excess property to be given for parks and recreation. A golf initiative proposed an 18-hole course. And Metro had its own plans for the Park’s beach. The missile base was moved. A treaty was signed. A federal law was passed. The golf initiative failed. And even Metro studied an off-site solution first suggested by Don. He named the park “Discovery” partly after Capt. George Vancouver’s ship. But even more “because when our children walk this park, discoveries will unfold for them at every turn.” History, beauty, nature and the future are melded here. -

Arts and Laughs ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH $ 00 OFF 3ANY CAR WASH! EXPIRES 8/31/18

FINAL-1 Sat, Jul 21, 2018 6:13:44 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of July 28 - August 3, 2018 HARTNETT’S Arts and laughs ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH $ 00 OFF 3ANY CAR WASH! EXPIRES 8/31/18 BUMPER Nick Offerman and Amy Hartnett's Car Poehler host “Making It” SPECIALISTS Wash H1artnett x 5` Auto Body, Inc. COLLISION REPAIR SPECIALISTS & APPRAISERS MA R.S. #2313 R. ALAN HARTNETT LIC. #2037 DANA F. HARTNETT LIC. #9482 15 WATER STREET DANVERS (Exit 23, Rte. 128) TEL. (978) 774-2474 FAX (978) 750-4663 Open 7 Days Mon.-Fri. 8-7, Sat. 8-6, Sun. 8-4 ** Gift Certificates Available ** Choosing the right OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Attorney is no accident FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Free Consultation PERSONAL INJURYCLAIMS • Automobile Accident Victims • Work Accidents • Slip &Fall • Motorcycle &Pedestrian Accidents John Doyle Forlizzi• Wrongfu Lawl Death Office INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY • Dog Attacks • Injuries2 x to 3 Children Voted #1 1 x 3 With 35 years experience on the North Insurance Shore we have aproven record of recovery Agency No Fee Unless Successful “Parks and Recreation” alumni Amy Poehler and Nick Offerman reunite in the artisanal The LawOffice of event of the summer to celebrate the creativity and craftiness in all of us. “Making It” STEPHEN M. FORLIZZI features artisans competing in themed challenges that are inspired by crafting and Auto • Homeowners DIY trends that test their creativity, skills and outside-the-box thinking — but there Business • Life Insurance 978.739.4898 can only be one Master Maker. Get inspired and laugh with the fun summer series pre- Harthorne Office Park •Suite 106 www.ForlizziLaw.com 978-777-6344 491 Maple Street, Danvers, MA 01923 [email protected] miering Tuesday, July 31, on NBC. -

Swing the Door Wide: World War II Wrought a Profound Transformation in Seattle’S Black Community Columbia Magazine, Summer 1995: Vol

Swing the Door Wide: World War II Wrought a Profound Transformation in Seattle’s Black Community Columbia Magazine, Summer 1995: Vol. 9, No. 2 By Quintard Taylor World War II was a pivotal moment in history for the Pacific Northwest, particularly for Seattle. The spectacular growth of Boeing, the "discovery" of the city and the region by tens of thousands of military personnel and defense workers, and the city's emergence as a national rather than regional center for industrial production, all attested to momentous and permanent change. The migration of over 10,000 African Americans to Seattle in the 1940s also represented a profound change that made the city - for good and ill - increasingly similar to the rest of urban America. That migration permanently altered race relations in Seattle as newcomers demanded the social freedoms and political rights denied them in their former Southern homes. The migration increased black political influence as reflected in the 1949 election of State Representative Charles Stokes as the city's first black officeholder. It strengthened civil rights organizations such as the NAACP and encouraged the enactment of antidiscrimination legislation in Washington for the first time since 1890. The wartime migration also increased racial tensions as the interaction of settlers and natives, white and black, came dangerously close to precipitating Seattle's first racial violence since the anti Chinese riot of 1886. Moreover, severe overcrowding was particularly acute in the black community and accelerated the physical deterioration of the Central District into the city's most depressed area. But tensions also rose within the black community as the mostly rural African Americans from Louisiana, Arkansas, Texas and Oklahoma faced the disdain of the "old settlers" blacks who had arrived in the city before 1940. -

10 That Changed America

10 That Changed America Episode Guide 10 Buildings That Changed America Explore 10 trend-setting works of architecture that have shaped and inspired the American landscape. These aren’t just historic structures by famous architects – they’re buildings with global influence that have dramatically changed the way people live, work, and play. Hosted by Geoffrey Baer, the program features striking videography, rare archival images, distinctive animation, and interviews with some of the most insightful historians and architects (including Frank Gehry and Robert Venturi). This is a journey that will take viewers inside these groundbreaking works of art and engineering. It is also a journey back in time, to discover the shocking, funny, and even sad stories of how these buildings came to be. And ultimately, it is a journey inside the imaginations of ten daring architects who set out to change the way we live, work, worship, learn, shop, and play. Buildings profiled include Frank Gehry’s Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, a Prairie-style home by Frank Lloyd Wright, Henry Ford’s first Model T factory, Dulles International Airport, and the Trinity Church in Boston designed by H.H. Richardson. 10 Homes That Changed America He was a successful lawyer, a violinist, the father of American archaeology, author of the Declaration of Independence, President of the United States, and a self-taught architect, who helped established his new nation’s sense of style. Thomas Jefferson’s designs for the Virginia State Capitol and the University of Virginia became models for statehouses and college campuses across the country. But it was his own home – inspired by classical temples, and elevated on an idyllic hilltop in Virginia – that Jefferson called his “essay in architecture.” Monticello was more than just an architectural statement; it was also a political one. -

Hybrid Landscapes: Toward an Inclusive Ecological Urbanism on Seattle's Central Waterfront

HYBRID LANDSCAPES 245 Hybrid Landscapes: Toward an Inclusive Ecological Urbanism on Seattle's Central Waterfront JEFFREY HOU University of Washington Urban Ecologies How would an inclusive approach of ecological urbanism address the imperatives of restoring Ecological design in the urban context faces a and enhancing the urban ecosystems while dual challenge of meeting ecological offering expressions of ecological and social imperatives and negotiating meaningful multiplicity in the urban environment? This expressions for the coexistence of urban paper examines a series of recent design infrastructure, human activities, and proposals for the Central Waterfront in Seattle ecological processes. In recent years, a that acknowledges the multiple constructions growing body of literature and examples of of social, ecological and economic processes in urban sustainable design has addressed issues this evolving urban edge. Specifically, the such as habitats restoration, stormwater analysis looks at how these hybrid design management, and energy and resource proposals respond to the ecological, economic, conservation. While such work have been and social demands on the City's waterfront important in building the necessary knowledge edge. The paper first describes the historical and experiences toward resolving problems of and developmental contexts for the recent ecological importance, there have not been explorations by various stakeholders in the adequate discussions on strategies of City, followed by a discussion of selected conceptual and tectonic expressions of works. It then examines the theoretical sustainability that embody the ecological and implications as well as practical challenges social complexity in the urban environment. and opportunities for a vision of inclusive The inadequacy is exemplified in the tendency ecological urbanism. -

Victor Steinbrueck Papers, 1931-1986

Victor Steinbrueck papers, 1931-1986 Overview of the Collection Creator Steinbrueck, Victor Title Victor Steinbrueck papers Dates 1931-1986 (inclusive) 1931 1986 Quantity 20.32 cubic feet (23 boxes and 1 package) Collection Number Summary Papers of a professor of architecture, University of Washington. Repository University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections. Special Collections University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 Seattle, WA 98195-2900 Telephone: 206-543-1929 Fax: 206-543-1931 [email protected] Access Restrictions Open to all users, but access to portions of the papers restricted. Contact Special Collection for more information Languages English Sponsor Funding for encoding this finding aid was partially provided through a grant awarded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Biographical Note Victor Steinbrueck was born in 1911 in Mandan, North Dakota and moved with his family to Washington in 1914. Steinbrueck attended the University of Washington, earning a Bachelor of Architecture degree in 1935. He joined the faculty at the University of Washington in 1946 and taught until his retirement in 1976. He was the author of Seattle Cityscape (1962), Seattle Cityscape II (1973) and a collections of his drawings, Market Sketchbook (1968). Victor Steinbrueck was Seattle's best known advocate of historic preservation. He led the battle against the city's redevelopment plans for the Pike Place Market in the 1960s. In 1959, the City of Seattle, together with the Central Association of Seattle, formulated plans to obtain a Housing and Urban Development (HUD) urban renewal grant to tear down the Market and everything else between First and Western, from Union to Lenora, in order to build a high rise residential, commercial and hotel complex. -

Oral History Interview with Alice Rooney, 2011 Aug. 5-12

Oral history interview with Alice Rooney, 2011 Aug. 5-12 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Alice Rooney on August 5 and 12, 2011. The interview took place in Seattle, Washington, and was conducted by Lloyd Herman for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. The Archives of American Art has reviewed the transcript and has made corrections and emendations. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview LLOYD HERMAN: This is Lloyd Herman interviewing Alice Rooney for the Archives of American Art in her home in Seattle on August 5, 2011. And, Alice, I think since we're going to kind of go from the very beginning, if you would give your full name and when and where you were born. ALICE ROONEY: My full name is Alice Gregor Rooney. Gregor was my maiden name—G-R-E-G-O-R. I was born in Seattle in 1926 on July 5. LLOYD HERMAN: And would you tell a little bit about your parents, because I think that's an interesting story too. ALICE ROONEY: My parents came from Norway. My father was the third of six brothers on a farm in Northern Norway. And he—they have, actually, the largest farm in Northern Norway. And I discovered recently it's been in our family since 1854, which is quite a long time. -

HEALTHY COMMUNITY a What You Need to Know to Give Strategically a HEALTHY COMMUNITY HEALTHY A

THE SEATTLE FOUNDATION HEALTHY COMMUNITY A What you need to Know to GIVE stRateGically A HEALTHY COMMUNITY AD LOCATION “I give to The Seattle Foundation because .” they help me personalize my giving –in bulk SEVEN Jeff Brotman, Chairman, Costco key categories One Making strategic decisions about where his money goes is something Costco Chairman Jeff Brotman knows a lot about. That’s community foundation why he partners with The Seattle Foundation. “The ability to team with a group who can support your giving is a huge asset,” he says. By handling the paperwork and eliminating the administrative hassles, we help Jeff support the things he cares about. All of which add up to a foundation that delivers smart giving by the truckload. www.seattlefoundation.org 206.622.2294 50+ 2006 effective programs 175 in King County promising strategies The following board members and donors participated in focus groups, community conversations and donor stories. The Seattle Foundation Trustees Rick Fox Peter Horvitz Kate Janeway Judy Runstad Dr. Al Thompson AFTER 60 YEARS, Maggie Walker Robert Watt The Seattle Foundation Donors THE SEATTLE FOUNDATION IS Fraser Black Peter Bladin and Donna Lou Linda Breneman Ann Corbett ENTERING A NEW ERA OF LEADERSHIP, Jane and David Davis Tom DesBrisay Sue Holt Kate Janeway HARNESSING INDIVIDUAL PHILANTHROPY Sally Jewell Jeanette Davis-Loeb Richard Miyauchi John Morse TO BUILD A STRONG COMMUNITY Dan Regis Robert Rudine and Janet Yoder Lynn Ryder Gross Maryanne Tagney Jones Doug and Maggie Walker FOR ALL RESIDENTS. Lindie Wightman Matthew Wiley and Janet Buttenwieser Barbara Wollner This report was made possible by our dedicated researchers, writers and editors: Nancy Ashley of Heliotrope; Sally Bock and Tana Senn of Pyramid Communications; Kathleen Sullivan; and Michael Brown and Molly Stearns of The Seattle Foundation. -

Monday-Tuesday April 11-12

Trusted. Valued. Essential. APRIL 2016 TWO-NIGHT EVENT MONDAY-TUESDAY APRIL 11-12 Vegas PBS A Message from the Management Team General Manager General Manager Tom Axtell, Vegas PBS Production Services Manager Kareem Hatcher Communications and Brand Management Director Shauna Lemieux Individual Giving Director Kelly McCarthy Business Manager Brandon Merrill Autism Awareness Content Director egas PBS offers programs that provide an in-depth look at the issues Cyndy Robbins affecting our community. During this National Autism Awareness Workforce Training & Economic Development Director Debra Solt Month, we focus on a condition that affects one out of every 68 children in our community. Our television and cable programming, media resource Corporate Partnerships Director Bruce Spotleson library, and outreach partners will work together to increase autism Vawareness, foster autism acceptance, and highlight resources in our community. Southern Nevada Public Television Board of Directors The programs this month include Children and Autism: Time Is Brain, which exam- Executive Director Tom Axtell, Vegas PBS ines the challenges faced by families raising children with autism and discusses diagno- President sis, early intervention and treatment. Bill Curran, Ballard Spahr, LLP Autism: Coming of Age follows three ...Our library expanded Vice President adults with autism including their fami- to include a variety of Nancy Brune, Guinn Center for Policy Priorities “ lies and support systems. In POV’s Best books and learning tools Secretary Kept Secret, educators in a New Jersey Barbara Molasky, Barbara Molasky and Associates public school work to secure resources that address autism...” Treasurer and Chair, Planned Giving Council for their students with severe autism Mark Dreschler, Premier Trust of Nevada before they graduate and age out of the system.