Understanding the Resiliency of the Kalamazoo Mall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8364 Licensed Charities As of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T

8364 Licensed Charities as of 3/10/2020 MICS 24404 MICS 52720 T. Rowe Price Program for Charitable Giving, Inc. The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust USA, Inc. 100 E. Pratt St 25283 Cabot Road, Ste. 101 Baltimore MD 21202 Laguna Hills CA 92653 Phone: (410)345-3457 Phone: (949)305-3785 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 Expiration Date: 10/31/2020 MICS 52752 MICS 60851 1 For 2 Education Foundation 1 Michigan for the Global Majority 4337 E. Grand River, Ste. 198 1920 Scotten St. Howell MI 48843 Detroit MI 48209 Phone: (425)299-4484 Phone: (313)338-9397 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 46501 MICS 60769 1 Voice Can Help 10 Thousand Windows, Inc. 3290 Palm Aire Drive 348 N Canyons Pkwy Rochester Hills MI 48309 Livermore CA 94551 Phone: (248)703-3088 Phone: (571)263-2035 Expiration Date: 07/31/2021 Expiration Date: 03/31/2020 MICS 56240 MICS 10978 10/40 Connections, Inc. 100 Black Men of Greater Detroit, Inc 2120 Northgate Park Lane Suite 400 Attn: Donald Ferguson Chattanooga TN 37415 1432 Oakmont Ct. Phone: (423)468-4871 Lake Orion MI 48362 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Phone: (313)874-4811 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 25388 MICS 43928 100 Club of Saginaw County 100 Women Strong, Inc. 5195 Hampton Place 2807 S. State Street Saginaw MI 48604 Saint Joseph MI 49085 Phone: (989)790-3900 Phone: (888)982-1400 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 Expiration Date: 07/31/2020 MICS 58897 MICS 60079 1888 Message Study Committee, Inc. -

Urban Growth Initiative for Greater Downtown Kalamazoo

Reports Upjohn Research home page 1-1-2018 Urban Growth Initiative for Greater Downtown Kalamazoo Jim Robey W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, [email protected] Randall W. Eberts W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, [email protected] Lee Adams W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research Kathleen Bolter W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research Don Edgerly W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://research.upjohn.org/reports Citation Robey, Jim, Randall W. Eberts, Lee Adams, Kathleen Bolter, Don Edgerly, Marie Holler, Brian Pittelko, Claudette Robey. 2018. "Urban Growth Initiative for Greater Downtown Kalamazoo." Prepared for the City of Kalamazoo and the Brownfield Redevelopment Authority. https://research.upjohn.org/reports/231 This title is brought to you by the Upjohn Institute. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Jim Robey, Randall W. Eberts, Lee Adams, Kathleen Bolter, Don Edgerly, Marie Holler, Brian Pittelko, and Claudette Robey This report is available at Upjohn Research: https://research.upjohn.org/reports/231 Urban Growth Initiative for Greater Downtown Kalamazoo Prepared for the City of Kalamazoo and the Brownfield Redevelopment Authority Initial draft: June 14, 2017 Final document issued: March 20, 2018 Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 Overview of Recommendations 7 Recommendations for Downtown Growth 14 Priority Objective: Business Recruitment and Retention -

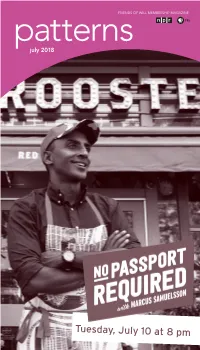

PDF Version of July 2018 Patterns

FRIENDS OF WILL MEMBERSHIP MAGAZINE patterns july 2018 Tuesday, July 10 at 8 pm WILL-TV TM patterns Membership Hotline: 800-898-1065 july 2018 Volume XLVI, Number 1 WILL AM-FM-TV: 217-333-7300 Campbell Hall 300 N. Goodwin Ave., Urbana, IL 61801-2316 Mailing List Exchange Donor records are proprietary and confidential. WILL does not sell, rent or trade its donor lists. Patterns Friends of WILL Membership Magazine Editor/Art Designer: Sarah Whittington Printed by Premier Print Group. Printed with SOY INK on RECYCLED, TM Trademark American Soybean Assoc. RECYCLABLE paper. Radio 90.9 FM: A mix of classical music and NPR information programs, including local news. (Also heard at 106.5 in Danville and with live streaming on will.illinois.edu.) See pages 4-5. 101.1 FM and 90.9 FM HD2: Locally produced music programs and classical music from C24. (101.1 The month of July means we’ve moved into a is available in the Champaign-Urbana area.) See page 6. new fiscal year here at Illinois Public Media. 580 AM: News and information, NPR, BBC, news, agriculture, talk shows. (Also heard on 90.9 FM HD3 First and foremost, I want to give a big thank with live streaming on will.illinois.edu.) See page 7. you to everyone who renewed or increased your gift to Illinois Public Media over the last Television 12 months. You continue to show your love and WILL-HD All your favorite PBS and local programming, in high support for what we do time and again. I am definition when available. -

Chapter 11 ) CHRISTOPHER & BANKS CORPORATION, Et Al

Case 21-10269-ABA Doc 125 Filed 01/27/21 Entered 01/27/21 15:45:17 Desc Main Document Page 1 of 22 TROUTMAN PEPPER HAMILTON SANDERS LLP Brett D. Goodman 875 Third Avenue New York, NY 1002 Telephone: (212) 704.6170 Fax: (212) 704.6288 Email:[email protected] -and- Douglas D. Herrmann Marcy J. McLaughlin Smith (admitted pro hac vice) Hercules Plaza, Suite 5100 1313 N. Market Street Wilmington, Delaware 19801 Telephone: (302) 777.6500 Fax: (866) 422.3027 Email: [email protected] [email protected] – and – RIEMER & BRAUNSTEIN LLP Steven E. Fox, Esq. (admitted pro hac vice) Times Square Tower Seven Times Square, Suite 2506 New York, NY 10036 Telephone: (212) 789.3100 Email: [email protected] Counsel for Agent UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY ) In re: ) Chapter 11 ) CHRISTOPHER & BANKS CORPORATION, et al., ) Case No. 21-10269 (ABA) ) ) (Jointly Administered) Debtors. 1 ) _______________________________________________________________________ 1 The Debtors in these chapter 11 cases and the last four digits of each Debtor’s federal tax identification number, as applicable, are as follows: Christopher & Banks Corporation (5422), Christopher & Banks, Inc. (1237), and Christopher & Banks Company (2506). The Debtors’ corporate headquarters is located at 2400 Xenium Lane North, Plymouth, Minnesota 55441. Case 21-10269-ABA Doc 125 Filed 01/27/21 Entered 01/27/21 15:45:17 Desc Main Document Page 2 of 22 DECLARATION OF CINDI GIGLIO IN SUPPORT OF DEBTORS’ MOTION FOR INTERIM AND FINAL ORDERS (A)(1) CONFIRMING, ON AN INTERIM BASIS, THAT THE STORE CLOSING AGREEMENT IS OPERATIVE AND EFFECTIVE AND (2) AUTHORIZING, ON A FINAL BASIS, THE DEBTORS TO ASSUME THE STORE CLOSING AGREEMENT, (B) AUTHORIZING AND APPROVING STORE CLOSING SALES FREE AND CLEAR OF ALL LIENS, CLAIMS, AND ENCUMBRANCES, (C) APPROVING DISPUTE RESOLUTION PROCEDURES, AND (D) AUTHORIZING CUSTOMARY BONUSES TO EMPLOYEES OF STORES I, Cindi Giglio, make this declaration pursuant to 28 U.S.C. -

Case 20-13076-BLS Doc 67 Filed 12/07/20 Page 1 of 14

Case 20-13076-BLS Doc 67 Filed 12/07/20 Page 1 of 14 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE ------------------------------------------------------------ x : In re: : Chapter 11 : Case No. 20-13076 (BLS) FRANCESCA’S HOLDINGS CORPORATION, : et al.,1 : Joint Administration Requested : Debtors. : Re: D.I. 8 ------------------------------------------------------------ x SUPPLEMENTAL DECLARATION OF SHERYL BETANCE IN SUPPORT OF THE DEBTORS’ APPLICATION FOR ENTRY OF AN ORDER AUTHORIZING THE RETENTION AND EMPLOYMENT OF STRETTO AS CLAIMS AND NOTICING AGENT, NUNC PRO TUNC TO THE PETITION DATE Pursuant to 28 U.S.C.§ 1746, I, Sheryl Betance, declare under penalty of perjury that the following is true and correct to the best of my knowledge, information, and belief: 1. I am a Senior Managing Director of Corporate Restructuring at Stretto, a chapter 11 administrative services firm with offices at 410 Exchange, Ste. 100, Irvine, CA 92602. Except as otherwise noted, I have personal knowledge of the matters set forth herein, and if called and sworn as a witness, I could and would testify competently thereto. 2. On December 3, 2020, the Debtors filed the Debtors’ Application for Entry of an Order Authorizing the Retention and Employment of Stretto as Claims and Noticing Agent, Nunc Pro Tunc to the Petition Date [D.I. 8] (the “Application”),2 and the Declaration of Sheryl Betance in Support of the Debtors’ Application for Entry of an Order Authorizing the Retention and 1 The Debtors in these cases, along with the last four digits of each Debtor’s federal tax identification number, are Francesca’s Holdings Corporation (4704), Francesca’s LLC (2500), Francesca’s Collections, Inc. -

Arts and Laughs ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH $ 00 OFF 3ANY CAR WASH! EXPIRES 8/31/18

FINAL-1 Sat, Jul 21, 2018 6:13:44 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of July 28 - August 3, 2018 HARTNETT’S Arts and laughs ALL SOFT CLOTH CAR WASH $ 00 OFF 3ANY CAR WASH! EXPIRES 8/31/18 BUMPER Nick Offerman and Amy Hartnett's Car Poehler host “Making It” SPECIALISTS Wash H1artnett x 5` Auto Body, Inc. COLLISION REPAIR SPECIALISTS & APPRAISERS MA R.S. #2313 R. ALAN HARTNETT LIC. #2037 DANA F. HARTNETT LIC. #9482 15 WATER STREET DANVERS (Exit 23, Rte. 128) TEL. (978) 774-2474 FAX (978) 750-4663 Open 7 Days Mon.-Fri. 8-7, Sat. 8-6, Sun. 8-4 ** Gift Certificates Available ** Choosing the right OLD FASHIONED SERVICE Attorney is no accident FREE REGISTRY SERVICE Free Consultation PERSONAL INJURYCLAIMS • Automobile Accident Victims • Work Accidents • Slip &Fall • Motorcycle &Pedestrian Accidents John Doyle Forlizzi• Wrongfu Lawl Death Office INSURANCEDoyle Insurance AGENCY • Dog Attacks • Injuries2 x to 3 Children Voted #1 1 x 3 With 35 years experience on the North Insurance Shore we have aproven record of recovery Agency No Fee Unless Successful “Parks and Recreation” alumni Amy Poehler and Nick Offerman reunite in the artisanal The LawOffice of event of the summer to celebrate the creativity and craftiness in all of us. “Making It” STEPHEN M. FORLIZZI features artisans competing in themed challenges that are inspired by crafting and Auto • Homeowners DIY trends that test their creativity, skills and outside-the-box thinking — but there Business • Life Insurance 978.739.4898 can only be one Master Maker. Get inspired and laugh with the fun summer series pre- Harthorne Office Park •Suite 106 www.ForlizziLaw.com 978-777-6344 491 Maple Street, Danvers, MA 01923 [email protected] miering Tuesday, July 31, on NBC. -

10 That Changed America

10 That Changed America Episode Guide 10 Buildings That Changed America Explore 10 trend-setting works of architecture that have shaped and inspired the American landscape. These aren’t just historic structures by famous architects – they’re buildings with global influence that have dramatically changed the way people live, work, and play. Hosted by Geoffrey Baer, the program features striking videography, rare archival images, distinctive animation, and interviews with some of the most insightful historians and architects (including Frank Gehry and Robert Venturi). This is a journey that will take viewers inside these groundbreaking works of art and engineering. It is also a journey back in time, to discover the shocking, funny, and even sad stories of how these buildings came to be. And ultimately, it is a journey inside the imaginations of ten daring architects who set out to change the way we live, work, worship, learn, shop, and play. Buildings profiled include Frank Gehry’s Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles, a Prairie-style home by Frank Lloyd Wright, Henry Ford’s first Model T factory, Dulles International Airport, and the Trinity Church in Boston designed by H.H. Richardson. 10 Homes That Changed America He was a successful lawyer, a violinist, the father of American archaeology, author of the Declaration of Independence, President of the United States, and a self-taught architect, who helped established his new nation’s sense of style. Thomas Jefferson’s designs for the Virginia State Capitol and the University of Virginia became models for statehouses and college campuses across the country. But it was his own home – inspired by classical temples, and elevated on an idyllic hilltop in Virginia – that Jefferson called his “essay in architecture.” Monticello was more than just an architectural statement; it was also a political one. -

Much Has Been Written Recently About the Necessity to Rethink Some of The

Rescaling Global Governance in the Midst of the Premature Demise of the Nation-State? Draft: Published 2012, Globalizations 9; 241-256 Kevin Archer University of South Florida Much has been written about the necessity to rethink some of the basic concepts of international relations theory to take better account of changes in government and governance in a rapidly globalizing world (Paul, 2005a, 2000b; Barnett and Sikkink, 2008). The usual focus on the sovereign nation-state as the primary actor on the international scene is giving way to the growing realization that nation-states are losing much of their sovereign decision-making powers to other levels of government, both upwards toward supranational governing institutions like the European Union, NAFTA, and the WTO and downwards to subnational state institutions at the regional or metropolitan territorial levels (Agnew, 2009). At least this is an increasingly popular argument on the part of those who believe that the contemporary process of globalization is wreaking substantive change in international political, as well as economic and cultural relations. If such a restructuring were happening, of course, it would necessitate a serious reconsideration of some of the fundamental assumptions of still dominant theories in international relations and political geography. Yet, much like the very notion of “globalization” as somehow different from previous periods of Western imperialism, such a view of contemporary geopolitics has met with no little resistance ( Lovering, 2001, 1999; Cox 2009, 2001). On this contrary view, the power of the nation-state has not dwindled in the face of the supposed growth of supra- and sub-national power but rather has actually facilitated these latter 1 emergences. -

In 1986, Chicago, and Urban America Generally, Was in Flux

Critique: A worldwide journal of politics Public Rhetoric, Private Development, And Urban Government In The Postindustrial City: The Case Of Chicago’s Navy Pier James M. Smith University of Illinois at Chicago As revenue-deprived cities in the United States depend more on developments aimed at attracting visitors, the governing bodies controlling this infrastructure play a larger role in urban government. This paper explores the case of one such development, Chicago’s Navy Pier. The author argues that the Pier’s redevelopment as a festival marketplace, which was based on public rhetoric and space, necessitated the creation of a public authority that compromised this vision. The paper begins with a description of the postindustrial city, then outlines the history of Navy Pier and its redevelopment, and closes with a discussion of the role of public authorities in the contemporary city. In 1986, Chicago and urban America generally, were in decline. The bedrock of federal urban funding had disappeared, middle class residents continued to flee the city for suburban enclaves, and manufacturing jobs that had once employed large portions of city dwellers were suddenly much scarcer. While cities searched for strategies to reverse these trends, most found great trouble in doing so. An urban regeneration seemed unlikely at the time, but cities would soon find ways to attract dollars, residents, and visitors back within their limits. Seventy years earlier, Municipal Pier, a mixed-use development for shipping and entertainment, was constructed near the mouth of the Chicago River and Lake Michigan. The initial uses of the structure known today as Navy Pier symbolize the industrial and leisure activities taking place in a rapidly growing, and at times, carefree urban setting. -

2021-2023 National Folk Festival Applications Now Being Accepted

THE NATIONAL 2021 - FOLK 2023 FESTIVAL A large-scale outdoor event presented free to the public, the National Folk Festival celebrates the richness and variety of American culture. It features a broad array of music and dance performances, workshops, storytelling, parades, dances, craft exhibitions and foodways. TH ENATIONAL FOLK FESTIVAL First presented in 1934, the National Folk Festival is the oldest multicultural traditional arts celebra - tion in the nation. Now entering its 79th year, this traveling festival has been held in 28 communities around the country. Musicians and craftspeople from every state in the Union and most U.S. territories have partici - pated in this “moveable feast of deeply traditional folk arts,” which is now attracting the largest audiences in its history. The National Council for the Traditional Arts (NCTA), the nation's premier folk and traditional arts presenting organization, is accepting applica - Aunt Samantha Bumgarner of Buncomb tions from cities and community partners to County, North Carolina, sang, fiddled and played her banjo at the second National in Chattanooga. Aunt Samantha was one of co-sponsor the National Folk Festival for the the first Appalachian women to record commercially, making her first 78-rpm discs three-year period 2021-2023. in 1924. The National Folk Festival, first held in St. Louis when I got home. I told my grandmother and in 1934, is the longest-running, most diverse she said, ‘Heaven will be like that.’” festival of traditional arts in the country and the event that defined this form of presentation. Its Creating new festivals most radical and enduring innovation was that Showcasing the nation’s finest traditional of putting the arts of many nations, races and musicians, dancers and craftspeople, the languages into the same event on equal footing. -

Union Station Indianapolis, Indiana Collection, 1882-1996

Collection # M 0876 OMB 0143 UNION STATION INDIANAPOLIS, INDIANA COLLECTION, 1882–1996 Collection Information Historical Sketch Scope and Content Note Contents Cataloging Information Processed by Emily Castle June 2006 Manuscript and Visual Collections Department William Henry Smith Memorial Library Indiana Historical Society 450 West Ohio Street Indianapolis, IN 46202-3269 www.indianahistory.org COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF Manuscript Materials: 6 manuscript boxes, 2 OMB boxes COLLECTION: Visual Materials: 2 photograph folders, 2 color photograph folders, 1 OVA color photograph folder COLLECTION 1882–1996 DATES: PROVENANCE: Woollen, Molzan & Partners, Inc., Indianapolis, IN, March 2002; City of Indianapolis, IN, August 2002 RESTRICTIONS: None COPYRIGHT: REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE FORMATS: RELATED M0780, OMB 0090 (Indianapolis Union railway company HOLDINGS: Maintenance of Way Department Records); SC 2130 (Union Station Records); P0157 Union Station Visual Collection ACCESSION 2002.0415; 2002.0692 NUMBER: NOTES: HISTORICAL SKETCH Originally built in 1853, Union Station had a dramatic effect on the growth and development of Indianapolis. The station prospered for decades serving up to 200 trains and thousands of people per day, including such notables as Abraham Lincoln, Woodrow Wilson, Theodore Roosevelt and Harry Truman. To accommodate the increasing number of travelers, Union Station’s original depot was replaced in 1888 by a three- story Romanesque-Revival style structure known today as the Grand Hall. Union Station was one of the earliest attempts by a major American city to unite the passenger and express freight services of several competing railroad companies in a single convenient downtown terminal. -

Lost and Found: the Process of Historic Preservation in Lucas

In Memory of my grandmother, Loretta J. Bowlin and my dear friend, Chester Lawson who will be greatly missed ii Acknowledgements There are a number of people that lent me their support, resources, and time to assist me in making this thesis successful. I am grateful to Dr. Diane F. Britton, my advisor, for her insight, guidance, support, and interest in this project. She has helped me to realize my potential to look further for the answers I seek. I would also like to thank Dr. Ruth Wallis Herndon for her continued support of my work when I faced tough times. Thank you to the history department for their advice and comments. I would especially like to thank my parents Dean and Marilyn and my fiancé, Ben for their faith in me throughout graduate school and for putting up with my constant procrastination. I appreciate everything you have done for me. iii Table of Contents Dedication ii Acknowledgements iii Table of Contents iv I. Introduction 1 II. The Historic Preservation Movement Before 1930 8 III. The Historic Preservation Movement After 1930 46 IV. The Decline of Historic Preservation in Lucas County, Ohio 96 V. The Historic Preservation Movement Takes Hold of Lucas 142 County, Ohio VI. The Lathrop House: Contemporary Controversy in 204 Preservation, A Case Study VII. Conclusion 227 VIII. Bibliography 235 IX. Appendix A 242 X. Appendix B 245 iv Introduction Historic preservation is the conservation of buildings, sites, and artifacts that are significant to American culture and history. In the past century, local history and the desire to find personal connections to the past have become prevalent across the country.