Tricksters from Three Folklore Traditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 6Th 1997

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Coyote Chronicle (1984-) Arthur E. Nelson University Archives 11-6-1997 November 6th 1997 CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/coyote-chronicle Recommended Citation CSUSB, "November 6th 1997" (1997). Coyote Chronicle (1984-). 419. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/coyote-chronicle/419 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Arthur E. Nelson University Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Coyote Chronicle (1984-) by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CALIFORNIA S^A^^UNlVERSITY The Coyote San Bernardino Volume 32 Issue 3 California State University, San Bernardino November 6,1997 Inside... CETI for California News State Universities rter By Jeanette Lee Production Editor ever have to step foot on the ac tual campus of the university that they would like to attend. Features What is CETI? What does CETI The CETI proposal would tack have to do with me? CETI is the a $14 technology fee on to student Califcmiia Educaticm Technology tuition. Faculty would also be re Initiative. This proposal was ccm- quired to pay this fee. ceived by Chancellor Barry Four major corpwations are set Opinio Munitzinl995. His intention was to be part of this new ccMporation Editoriais to fonn a separate corporation that to provide the CSU system tech would provide the CSU commu nological goods and sovices. The ....page 9 nity with internet services and four companies that will be part of computer technology and soft this corporation are MicroSoft, ware. -

Strategizing Renewal of Memories and Morals in the African Folktale

Revista África e Africanidades - Ano 3 - n. 11, novembro, 2010 - ISSN 1983-2354 www.africaeafricanidades.com Strategizing renewal of memories and morals in the african folktale John Rex Amuzu Gadzekpo1 Orquídea Ribeiro2 “As histórias são sempre as da minha infância. Cresci no meio de contadores de histórias: os meus avôs, e sobretudo a minha avó, e também a minha mãe, os meus irmãos mais velhos. Estou a ver-me sentado debaixo do canhoeiro, a ouvir … Essas histórias estavam ligadas à mitologia ronga, a fabulas, e eram encaradas como um contributo para a nossa formação moral.” Malangatana Valente Ngwenya3 Introduction In Africa, keeping oral traditions alive is a way of transmitting history and culture and of preserving individual and collective memories, as well as a matter of survival for the individual and the society in which he lives, for it allows the knowledge and experiences of the older generations to be transmitted to the younger ones. Considered in their historical dimension, oral traditional genres which relate past events and have been passed down through time cannot be dismissed simply as “myth,” as they are effectively the source for the construction of African history and are as reliable as other non-oral ways of recording and passing on experiences. For Amadou Hampaté Bâ “tradition transmitted orally is so precise and so rigorous that one can, with various kinds of cross checking, reconstruct the great events of centuries past in the minutest detail, especially the lives of the great empires or the great men who distinguish history”. His saying “In Africa, when an old man dies, a library disappears” has become so famous that is sometimes mistaken for an African proverb”: African knowledge is a global knowledge and living knowledge, and it is because the old people are often seen as the last repository of this knowledge that they can be compared to vast libraries whose multiple shelves are connected by invisible links which constitute precisely this 1 Ph.D., Investigador da Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro - Centro de Estudos em Letras. -

Is There Life on Europa? Theses That Allow South African Runner Oscar Pistorius to Compete with Able-Bodied Athletes — Are Left to Later Sections

OPINION NATURE|Vol 457|22 January 2009 Superman born of a 1930s United States adopting eugenic practices, to the nuclear- powered Spider-Man of the cold-war era and the psychologically disturbed Batman incar- nations of the therapy-obsessed 1980s and 1990s, every generation has its super people. Those portrayed in Heroes are the genetically enhanced Generation X of the superhero world — too busy to save the world because their own lives are in perpetual turmoil. Societies get the superheroes they need most. Human Futures and The Science of Many of the ‘superpowers’ portrayed in the television series Heroes are no longer science fiction. Heroes give a tantalizing glimpse of how science might make this a reality in a future but misplaced essay on ‘evidence dolls’, the powers, such as the ability to steal memory, are human existence. And given Carts-Powell’s creation of designers Anthony Dunne and already with us in the form of drugs that help talent for explaining the science, perhaps an Fiona Raby. The plastic miniatures are a victims of trauma to forget. army of her clones will take over high-school hypothetical future product in which to store Historically, superheroes are a snapshot of education. ■ sperm and hair samples of prospective repro- the relationship between science and society Arran Frood is a science writer based in the NBC UNIVERSAL PHOTO ductive partners. The dolls are personified by at any one time, based on their powers and United Kingdom. four women, who reveal how knowledge of how they obtained them. From the perfect e-mail: [email protected] their partner’s genes might influence their sexual and reproductive lifestyles. -

Anansi Folktales

Afro-Quiz Study Material 13-14 2018 Anansi Folktales Folktales are a means of handing down traditions, values, and customs from one generation to the next. The stories are not only for entertainment but also teach a moral lesson. Anansi stories are one example of African folktales. Anansi stories are well known in many parts of Western Africa, the Caribbean, and North America. These stories are an example of how elements of African culture travelled with enslaved Africans who were forcibly taken from the continent to work on plantations in the Americas. In this module you will learn who Anansi is, where the Anansi stories originate from and why they are an important part of many cultures in Africa and people of African descent who live in other parts of the world. Here is a list of activities you will work on: - KWL Chart - Reading - Listening / Video - Summary - Map Activities KWL Chart K W L 1 Afro-Quiz Study Material 13-14 2018 What I know about Anansi What I want to know What I learned about stories about Anansi stories Anansi stories Reading Anansi1 Anansi is an African folktale character. He often takes the shape of a spider and is one of the most important characters of West African and Caribbean folklore. He is also known as Ananse, Kwaku Ananse, and Anancy. The Anansi tales originated from the Akan people of present-day Ghana. The word Ananse is Akan and means "spider". According to legend, Kweku Anansi (or Ananse) is the son of Nyame, the Asanti (Ashanti) supreme being. -

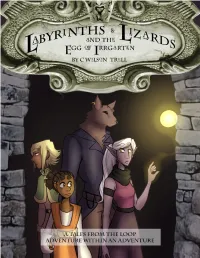

Labyrinths & Lizards Module

Labyrinths & Lizards Page !1 Labyrinths & Lizards and the Egg or Irrgarten Introduction 3 meta-Character Creation 3 meta-Classes 3 meta-Health 4 meta-Spells 4 meta-Items 5 meta-Name 5 A fnal note about notes. 5 Deep in the Labyrinth... 6 Room 1 10 Room 2 12 Room 3 15 NEXT CHALLENGE 18 Smashing the Harness Engine 20 Once it is all over 20 End of the game 20 Plunder Chart 21 meta-NPCs 22 Prerolled meta-Characters 23 Lolinda 23 MoonDaze 23 Capt. Cheese 23 Trizz 23 Acknowledgements 24 IMPORTANT NOTE: Tis game was designed to play with the Tales from the Loop RPG core book. Request it at your local game store or visit their sight, you will not be disappointed. http://frialigan.se/en/ Labyrinths & Lizards Page !2 Introduction Labyrinths & Lizards is a module I created to help my new players with transitioning from a fantasy hack-n-slash style to a more story building-mystery based RPG like Tales from the Loop. The idea came from my experiences joining an after school RPG club back in my early teens (in the 80s that actually was). This was around the same age an time period of Tales from the Loop so I felt it was a perfect idea to help introduce the players. In Labyrinths & Lizards, their player-characters travel to the North Street Rec Center and play a mini meta-RPG with an NPC named Joshua (who later became a major NPC in our campaign). Players will use their Tales from the Loop PCs skills to roll the dice for their meta-Characters., and each room is designed to help them learn and understand their STATS & SKILLS for the Tales from the Loop game. -

R2d2 Drives Selfish Sweeps in the House Mouse John P

R2d2 Drives Selfish Sweeps in the House Mouse John P. Didion,†,1,2,3* Andrew P. Morgan,†,1,2,3 Liran Yadgary,1,2,3 Timothy A. Bell,1,2,3 Rachel C. McMullan,1,2,3 Lydia Ortiz de Solorzano,1,2,3 Janice Britton-Davidian,4 Carol J. Bult,5 Karl J. Campbell,6,7 Riccardo Castiglia,8 Yung-Hao Ching,9 Amanda J. Chunco,10 James J. Crowley,1 Elissa J. Chesler,5 Daniel W. Forster,€ 11 John E. French,12 Sofia I. Gabriel,13 Daniel M. Gatti,5 Theodore Garland Jr,14 Eva B. Giagia-Athanasopoulou,15 Mabel D. Gimenez,16 Sofia A. Grize,17 _Islam Gund€ uz,€ 18 Andrew Holmes,19 Heidi C. Hauffe,20 Jeremy S. Herman,21 James M. Holt,22 Kunjie Hua,1 Wesley J. Jolley,23 Anna K. Lindholm,17 Marıa J. Lopez-Fuster, 24 George Mitsainas,15 MariadaLuzMathias,13 Leonard McMillan,22 MariadaGrac¸a Morgado Ramalhinho,13 Barbara Rehermann,25 Stephan P. Rosshart,25 Jeremy B. Searle,26 Meng-Shin Shiao,27 Emanuela Solano,8 Karen L. Svenson,5 Patricia Thomas-Laemont,10 David W. Threadgill,28,29 Jacint Ventura,30 George M. Weinstock,31 Daniel Pomp,1,3 Gary A. Churchill,5 and Fernando Pardo-Manuel de Villena*,1,2,3 1Department of Genetics, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 2Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 3Carolina Center for Genome Science, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 4Institut des Sciences de l’Evolution, Universite De Montpellier, CNRS, IRD, EPHE, Montpellier, France 5The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME 6Island Conservation, Puerto Ayora, Galapagos Island, Ecuador 7School of Geography, -

A History of Herring Lake; with an Introductory Legend, the Bride of Mystery

Library of Congress A history of Herring Lake; with an introductory legend, The bride of mystery THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 1800 Class F572 Book .B4H84 Copyright No. COPYRIGHT DEPOSIT. A HISTORY OF HEARING LAKE JOHN H. HOWARD HISTORY OF HERRING LAKE WITH INTRODUCTORY LEGEND THE BRIDE OF MYSTERY BY THE BARD OF BENZIE (John H. Howard) CPH The Christopher Publishing House Boston, U.S.A F572 B4 H84 COPYRIGHT 1929 BY THE CHRISTOPHER PUBLISHING HOUSE 29-22641 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ©C1A 12472 SEP 21 1929 DEDICATION TO MY COMPANION AND HELPMEET FOR ALMOST TWO SCORE YEARS; TO THE STURDY PIONEERS WHOSE ADVENTUROUS SPIRIT ATTRACTED THE ATTENTION OF THEIR FOLLOWERS TO HERRING LAKE AND ITS ENVIRONS; TO MY LOYAL SWIMMING PLAYMATES, YOUNG AND OLD; TO THE GOOD NEIGHBORS WHO HAVE LABORED SHOULDER TO SHOULDER WITH ME IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF OUR LOCAL RESOURCES; AND TO MY NEWER AND MOST WELCOME NEIGHBORS WHO COME TO OUR LOVELY LITTLE LAKE FOR REJUVENATION OF MIND AND BODY— TO ALL THESE THIS LITTLE VOLUME OF LEGEND AND ANNALS IS REVERENTLY AND RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED TABLE OF CONTENTS A history of Herring Lake; with an introductory legend, The bride of mystery http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbum.22641 Library of Congress The Bride of Mystery 9 A History of Herring Lake 19 The Fist Local Sawmill 23 “Sam” Gilbert and His Memoirs 24 “Old Averill” and His Family 26 Frankfort's First Piers 27 The Sawmill's Equipment 27 Lost in the Hills 28 Treed by Big Bruin 28 The Boat Thief Gets Tar and Feathers 28 Averill's Cool Treatment of “Jo” Oliver 30 Indian -

Thomas Paine

I THE WRITINGS OF THOMAS PAINE COLLECTED AND EDITED BY MONCURE DANIEL CONWAY AUTHOR OF L_THE LIFR OF THOMAS PAINE_ y_ _ OMITTED CHAPTERS OF HISTOIY DI_LOSED IN TH I_"LIFE AND PAPERS OF EDMUND RANDOLPH_ tt _GEORGE W_HINGTON AND MOUNT VERNON_ _P ETC. VOLUME I. I774-I779 G. P. Pumam's Sons New York and London _b¢ "lkntckcrbo¢#¢_ I_¢ee COPYRIGHT, i8g 4 BY G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS Entered at Stationers' Hall, London BY G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS CONTENTS. PAGB INTRODUCTION V PREFATORY NOTE TO PAINE'S FIRST ESSAY , I I._AFRICAN SLAVERY IN AMERICA 4 II.--A DIALOGUE BETWEEN GENERAL WOLFE AND GENERAL GAGE IN A WOOD NEAR BOSTON IO III.--THE MAGAZINE IN AMERICA. I4 IV.--USEFUL AND ENTERTAINING HINTS 20 V._NEw ANECDOTES OF ALEXANDER THE GREAT 26 VI.--REFLECTIONS ON THE LIFE AND DEATH OF LORD CLIVE 29 VII._CUPID AND HYMEN 36 VIII._DUELLING 40 IX._REFLECTIONS ON TITLES 46 X._THE DREAM INTERPRETED 48 XI._REFLECTIONS ON UNHAPPY MARRIAGES _I XII._THOUGHTS ON DEFENSIVE WAR 55 XIII.--AN OCCASIONAL LETTER ON THE FEMALE SEX 59 XIV._A SERIOUS THOUGHT 65 XV._COMMON SENSE 57 XVI._EPISTLE TO QUAKERS . I2I XVII.--THE FORESTER'SLETTERS • I27 iii _v CONTENTS. PAGE XVIII.mA DIALOGUE. I6I XIX.--THE AMERICAN CRISIS . I68 XX._RETREAT ACROSS THE DELAWARE 38I XXI.--LETTER TO FRANKLIN, IN PARIS . 384 XXII.--THE AFFAIR OF SILAS DEANE 39S XXIII.--To THE PUBLm ON MR. DEANE'S A_FAIR 409 XXIV.mMEssRs. DEANS, JAY, AND G_RARD 438 INTRODUCTION. -

Tales of Clemson, 1936-1940 Arthur V

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Clemson University: TigerPrints Clemson University TigerPrints Monographs Clemson University Digital Press 2002 Tales of Clemson, 1936-1940 Arthur V. Williams, M.D. Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/cudp_mono Recommended Citation Tales of Clemson, 1936-1940, by Arthur V. Williams, M.D. (Clemson, SC: Clemson University Digital Press, 2002), viii, 96 pp. Paper. ISBN 0-9741516-4-5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Clemson University Digital Press at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Monographs by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tales of Clemson, 1936-1940 i ii Tales of Clemson 1936-1940 Arthur V. Williams, M.D. iii A full-text digital version of this book is available on the Internet, in addition to other works of the press and the Center for Electronic and Digital Publishing, including The South Carolina Review and The Upstart Crow:A Shakespeare Jour- nal. See our website at www.clemson.edu/caah/cedp, or call the director at 864- 656-5399 for information. Tales of Clemson 1936-1940 is made possible by a gift from Dialysis Clinics, Inc. Copyright 2002 by Clemson University Published by Clemson University Digital Press at the Center for Electronic and Digital Publishing, College of Architecture, Arts, and Humanities, Clemson Uni- versity, Clemson, South Carolina. Produced in the MATRF Laboratory at Clemson University using Adobe Photoshop 5.5 , Adobe Pagemaker 6.5, Microsoft Word 2000. -

Since I Began Reading the Work of Steve Ditko I Wanted to Have a Checklist So I Could Catalogue the Books I Had Read but Most Im

Since I began reading the work of Steve Ditko I wanted to have a checklist so I could catalogue the books I had read but most importantly see what other original works by the illustrator I can find and enjoy. With the help of Brian Franczak’s vast Steve Ditko compendium, Ditko-fever.com, I compiled the following check-list that could be shared, printed, built-on and probably corrected so that the fan’s, whom his work means the most, can have a simple quick reference where they can quickly build their reading list and knowledge of the artist. It has deliberately been simplified with no cover art and information to the contents of the issue. It was my intension with this check-list to be used in accompaniment with ditko-fever.com so more information on each publication can be sought when needed or if you get curious! The checklist only contains the issues where original art is first seen and printed. No reprints, no messing about. All issues in the check-list are original and contain original Steve Ditko illustrations! Although Steve Ditko did many interviews and responded in letters to many fanzines these were not included because the checklist is on the art (or illustration) of Steve Ditko not his responses to it. I hope you get some use out of this check-list! If you think I have missed anything out, made an error, or should consider adding something visit then email me at ditkocultist.com One more thing… share this, and spread the art of Steve Ditko! Regards, R.S. -

The Shifting Contexts of Anansi's Metamorphosis

EMILY ZOBEL MARSHALL Emily Zobel Marshall has been lecturing at the School of Cultural Studies at Leeds Metropolitan University for four years and is undertaking a PhD entitled ‘The Journey of Anansi: An exploration of Jamaican Cultural resistance.’ The main emphasis her research is an exploration of the ways in which the Anansi tales, as cultural forms, may have facilitated methods of resistance and survival during the plantation era. ______________________________________________________________________________ The Society For Caribbean Studies Annual Conference Papers edited by Sandra Courtman Vol.7 2006 ISSN 1471-2024 http://www.scsonline.freeserve.co.uk/olvol7.html ______________________________________________________________________________ From Messenger of the Gods to Muse of the People: The Shifting Contexts of Anansi’s Metamorphosis. 1 Emily Zobel Marshall Abstract Anansi, trickster spider and national Jamaican folk hero, has his roots amongst the Asante of West Africa. Amongst the Asante Anansi played the role of messenger between the gods and mankind. The Asante Anansi possessed the power to restructure both the world of the human and the divine, and his tales played a key role as complex and philosophical commentaries on Asante spiritual and social life. In Jamaica his interaction with the gods was lost as he became a muse to the people, representing the black slave trapped in an abhorrent social system, and his devious and individualistic characteristics inspired strategies of survival. 1 However, in the face of rising crime and violence in Jamaica today many argue that these survival strategies are being misdirected towards fellow citizens rather than implemented to thwart oppressive powers. Drawing from interviews conducted on the Island, this paper explores whether it time for Anansi to metamorphose once again, and asks if he can he still provide a form of spiritual guidance to the Jamaican people. -

Zanzibar: Its History and Its People

Zanzibar: its history and its people http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.CH.DOCUMENT.PUHC025 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Zanzibar: its history and its people Author/Creator Ingrams, W.H. Publisher Frank Cass & Co., Ltd. Date 1967 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Northern Swahili Coast, Tanzania, United Republic of, Zanzibar Stone Town, Tanzania Source Princeton University Library 1855.991.49 Rights By kind permission of Leila Ingrams. Description Contents: Preface; Introductory; Zanzibar; The People; Historical; Early History and External Influences; Visitors from the Far East; The Rise and Fall of the Portuguese; Later History of the Native Tribes; History of Modern Zanzibar.