Volume 07 Number 03

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

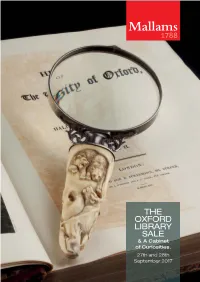

THE OXFORD LIBRARY SALE & a Cabinet of Curiosities

Mallams 1788 THE OXFORD LIBRARY SALE & A Cabinet of Curiosities. 27th and 28th September 2017 Chinese, Indian, Islamic & Japanese Art One of a pair of 25th & 26th October 2017 Chinese trade paintings, Final entries by September 27th 18th century £3000 – 4000 Included in the sale For more information please contact Robin Fisher on 01242 235712 or robin.fi[email protected] Mallams Auctioneers, Grosvenor Galleries, 26 Grosvenor Street Mallams Cheltenham GL52 2SG www.mallams.co.uk 1788 Jewellery & Silver A natural pearl, diamond and enamel brooch, with fitted Collingwood Ltd case Estimate £6000 - £8000 Wednesday 15th November 2017 Oxford Entries invited Closing date: 20th October 2017 For more information or to arrange a free valuation please contact: Louise Dennis FGA DGA E: [email protected] or T: 01865 241358 Mallams Auctioneers, Bocardo House, St Michael’s Street Mallams Oxford OX1 2EB www.mallams.co.uk 1788 BID IN THE SALEROOM Register at the front desk in advance of the auction, where you will receive a paddle number with which to bid. Take your seat in the saleroom and when you wish to bid, raide your paddle and catch the auctioneer’s attention. LEAVE A COMMISSION BID You may leave a commission bid via the website, by telephone, by email or in person at Mallams’ salerooms. Simply state the maximum price you would like to pay for a lot and we will purchase it for you at the lowest possible price, while taking the reserve price and other bids into account. BID OVER THE TELEPHONE Book a telephone line before the sale, stating which lots you would like to bid for, and we will call you in time for you to bid through one of our staff in the saleroom. -

Cake and Cockhorse

CAKE AND COCKHORSE BANBURLY HISTORICAL SOCIETY SUEWfR 1989 PRICE 51.0C VOLUME 11 NUMBER 3 ISSN 6522-0823 Bun6ury Historicat Society President: The Lord Saye and Sele Chairman: Dr. J.S. Rivers, Homeland, Middle Lane, Balscote, Banbury. Deputy Chairman: J.S.W. Gibson, Harts Cottage, Church Hanborough, Oxford, OX7 2AB Magazine Editor: D.A. Hitchcox, 1 Dorchester Grove, Banbury, OX16 OBD (Tel: 53733) Hon. Secretary: Hon. Treasurer: Mrs. M. Barnett, A. Essex-Crosby; Banbury Museum, 3 Brantwood Court, 8 Horsefair, Banbury Banbury. (Tel: 59855) (Tel: 56238) Programme Secretary: Hon. Research Adviser: Miss P. Renold M.A.F. R.Hist.S., J.S.W. Gibson, 51 Woodstock Close, Harts Cottage, Oxford OX2 8dd Church Hanborough, Oxford OX7 2AB (Tel: Oxford 53937) (lel: Freeland (0993)882982) Cmittee Members: Mrs. J.P. Bowes, Mrs. N.M. Clifton, Miss M. Stanton Details about the Society's activities and publications can be found on the inside back cover cuke and Cockhorse The Magazine of the Banbury Historical Society issued three times a year Volume 11 Number 3 Summer 1989 J.W.D. Davies Portrait of a Country Grocers Dossetts - Grocers and Wine Merchants - 1887-1973 54 Nanette Godfrey & Wykham - Early Times Until the Charmian Snowden End of the Seventeenth Century 65 E.R. Lester A History of the Neithrop Association For the Protection of Persons & Property 69 E.R. Lestxr & The Articles of the Neithrop Association Association For the Protection of Persons & Property Est. November 23rd 1819 74 Summer is a little late this year owing mainly to a lack of "COPY". It is important that I receive articles or ideas for articles. -

OXONIENSIA PRINT.Indd 253 14/11/2014 10:59 254 REVIEWS

REVIEWS Joan Dils and Margaret Yates (eds.), An Historical Atlas of Berkshire, 2nd edition (Berkshire Record Society), 2012. Pp. xii + 174. 164 maps, 31 colour and 9 b&w illustrations. Paperback. £20 (plus £4 p&p in UK). ISBN 0-9548716-9-3. Available from: Berkshire Record Society, c/o Berkshire Record Offi ce, 9 Coley Avenue, Reading, Berkshire, RG1 6AF. During the past twenty years the historical atlas has become a popular means through which to examine a county’s history. In 1998 Berkshire inspired one of the earlier examples – predating Oxfordshire by over a decade – when Joan Dils edited an attractive volume for the Berkshire Record Society. Oxoniensia’s review in 1999 (vol. 64, pp. 307–8) welcomed the Berkshire atlas and expressed the hope that it would sell out quickly so that ‘the editor’s skills can be even more generously deployed in a second edition’. Perhaps this journal should modestly refrain from claiming credit, but the wish has been fulfi lled and a second edition has now appeared. Th e new edition, again published by the Berkshire Record Society and edited by Joan Dils and Margaret Yates, improves upon its predecessor in almost every way. Advances in digital technology have enabled the new edition to use several colours on the maps, and this helps enormously to reveal patterns and distributions. As before, the volume has benefi ted greatly from the design skills of the Department of Typography and Graphic Communication at the University of Reading. Some entries are now enlivened with colour illustrations as well (for example, funerary monuments, local brickwork, a workhouse), which enhance the text, though readers could probably have been left to imagine a fl ock of sheep grazing on the Downs. -

Primary School Programme 2017/18

PRIMARY SCHOOL PROGRAMME 2017/18 SPONSORED BY WWW.BANBURYMUSEUM.ORG WELCOME TO THE BANBURY MUSEUM’S SCHOOLS PROGRAMME FOR 2017/18 WITH A STUNNING POSITION OVERLOOKING THE OXFORD CANAL AND A PROGRAMME PACKED FULL OF NEW WORKSHOPS, WE LOOK FORWARD TO MEETING NEW AND FAMILIAR SCHOOLS THIS YEAR. Suzi Wild – Education Manager SUPPORT TO SCHOOLS MUSEUM ADVISORY SERVICE We can come to your school to develop a workshop or devise resources which will support your topic/ curriculum planning. Please note this is a free service but geographical restrictions apply to this service. BANBURY MUSEUM – ‘KEEPING CONNECTED’ NETWORK The ‘Keeping Connected’ network is free to join with exclusive benefits to members including invitations to pilot new museum workshops and advanced information on forthcoming museum workshops and resources. To join the network please contact Suzi Wild – Education Manager. 2 BANBURY MUSEUM | PRIMARY SCHOOL PROGRAMME 2017/18 NOT TO BE MISSED IN 2017/18 OUR SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS THIS YEAR INCLUDE… BRICK WONDERS 16 SEPTEMBER TO 18 NOVEMBER 2017 CALLING ALL LEG0® OR BUILDERS… A world of imagination and creativity is awaiting your pupils! Marvel at the shapes and structures that can be snapped together the create the most iconic wonders of the world like the Great Wall of China, the Great Pyramid of Giza and Niagara Falls. For more information on the special Kindly Sponsored by programme and costs contact Suzi Wild – Education Manager. ‘TAKE ONE’ PICTURE WITH US ‘Take One Picture’ is simply brilliant and “A MASSIVE THANK YOU. IT HAS encourages imaginative cross-curricular BEEN AMAZING,EVERYONE HAS teaching and curious minds. -

Open Gardens

Festival of Open Gardens May - September 2014 Over £30,000 raised in 4 years Following the success of our previous Garden Festivals, please join us again to enjoy our supporters’ wonderful gardens. Delicious home-made refreshments and the hospice stall will be at selected gardens. We are delighted to have 34 unique and interesting gardens opening this year, including our hospice gardens in Adderbury. All funds donated will benefit hospice care. For more information about individual gardens and detailed travel instructions, please see www.khh.org.uk or telephone 01295 812161 We look forward to meeting you! Friday 23 May, 1pm - 6pm, Entrance £5 to both gardens, children free The Little Forge, The Town, South Newington OX15 4JG (6 miles south west of Banbury on the A361. Turn into The Town opposite The Duck on the Pond PH. Located on the left opposite Green Lane) By kind permission of Michael Pritchard Small garden with mature trees, shrubs and interesting features. Near a 12th century Grade 1 listed gem church famous for its wall paintings. Hospice stall. Wheelchair access. Teas at South Newington House (below). Sorry no dogs. South Newington House, Barford Rd, OX15 4JW (Take the Barford Rd off A361. After 100 yds take first drive on left. If using sat nav use postcode OX15 4JL) By kind permission of Claire and David Swan Tree lined drive leads to 2 acre garden full of unusual plants, shrubs and trees. Richly planted herbaceous borders designed for year-round colour. Organic garden with established beds and rotation planting scheme. Orchard of fruit trees with pond. -

POLITICS, SOCIETY and CIVIL WAR in WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History

Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History Series editors ANTHONY FLETCHER Professor of History, University of Durham JOHN GUY Reader in British History, University of Bristol and JOHN MORRILL Lecturer in History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow and Tutor of Selwyn College This is a new series of monographs and studies covering many aspects of the history of the British Isles between the late fifteenth century and the early eighteenth century. It will include the work of established scholars and pioneering work by a new generation of scholars. It will include both reviews and revisions of major topics and books which open up new historical terrain or which reveal startling new perspectives on familiar subjects. It is envisaged that all the volumes will set detailed research into broader perspectives and the books are intended for the use of students as well as of their teachers. Titles in the series The Common Peace: Participation and the Criminal Law in Seventeenth-Century England CYNTHIA B. HERRUP Politics, Society and Civil War in Warwickshire, 1620—1660 ANN HUGHES London Crowds in the Reign of Charles II: Propaganda and Politics from the Restoration to the Exclusion Crisis TIM HARRIS Criticism and Compliment: The Politics of Literature in the Reign of Charles I KEVIN SHARPE Central Government and the Localities: Hampshire 1649-1689 ANDREW COLEBY POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, i620-1660 ANN HUGHES Lecturer in History, University of Manchester The right of the University of Cambridge to print and sell all manner of books was granted by Henry VIII in 1534. -

Service 488: Chipping Norton - Hook Norton - Bloxham - Banbury

Service 488: Chipping Norton - Hook Norton - Bloxham - Banbury MONDAYS TO FRIDAYS Except public holidays Effective from 02 August 2020 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 488 489 Chipping Norton, School 0840 1535 Chipping Norton, Cornish Road 0723 - 0933 33 1433 - 1633 1743 1843 Chipping Norton, West St 0650 0730 0845 0940 40 1440 1540 1640 1750 1850 Over Norton, Bus Shelter 0654 0734 0849 0944 then 44 1444 1544 1644 1754 - Great Rollright 0658 0738 0853 0948 at 48 1448 1548 1648 1758 - Hook Norton Church 0707 0747 0902 0957 these 57 Until 1457 1557 1657 1807 - South Newington - - - - times - - - - - 1903 Milcombe, Newcombe Close 0626 0716 0758 0911 1006 each 06 1506 1606 1706 1816 - Bloxham Church 0632 0721 0804 0916 1011 hour 11 1511 1611 1711 1821 1908 Banbury, Queensway 0638 0727 0811 0922 1017 17 1517 1617 1717 1827 1914 Banbury, Bus Station bay 7 0645 0735 0825 0930 1025 25 1525 1625 1725 1835 1921 SATURDAYS 488 488 488 488 488 489 Chipping Norton, Cornish Road 0838 0933 33 1733 1833 Chipping Norton, West St 0650 0845 0940 40 1740 1840 Over Norton, Bus Shelter 0654 0849 0944 then 44 1744 - Great Rollright 0658 0853 0948 at 48 1748 - Hook Norton Church 0707 0902 0957 these 57 Until 1757 - South Newington - - - times - - 1853 Milcombe, Newcombe Close 0716 0911 1006 each 06 1806 - Bloxham Church 0721 0916 1011 hour 11 1811 1858 Banbury, Queensway 0727 0922 1017 17 1817 1904 Banbury, Bus Station bay 7 0735 0930 1025 25 1825 1911 Sorry, no service on Sundays or Bank Holidays At Easter, Christmas and New Year special timetables will run - please check www.stagecoachbus.com or look out for seasonal publicity This timetable is valid at the time it was downloaded from our website. -

Job 124253 Type

A SPLENDID GRADE II LISTED FAMILY HOUSE WITH 4 BEDROOMS, IN PRETTY ISLIP Greystones, Middle Street, Islip, Oxfordshire OX5 2SF Period character features throughout with an impressive modern extension and attractive gardens Greystones, Middle Street, Islip, Oxfordshire OX5 2SF 2 reception rooms ◆ kitchen/breakfast/family room ◆ utility ◆ cloakroom ◆ master bedroom with walk-in wardrobe and en suite shower room ◆ 3 additional bedrooms ◆ play room ◆ 2 bathrooms ◆ double garage ◆ gardens ◆ EPC rating = Listed Building Situation Islip mainline station 0.2 miles (52 minutes to London Marylebone), Kidlington 2.5 miles, M40 (Jct 9) 4.2 miles, Oxford city centre 4.5 miles Islip is a peaceful and picturesque village, conveniently located just four miles from Oxford and surrounded by beautiful Oxfordshire countryside. The village has two pubs, a doctor’s surgery and a primary school. The larger nearby village of Kidlington offers a wide range of shops, supermarkets and both primary and secondary schools. A further range of excellent schools can also be found in Oxford, along with first class shopping, leisure and cultural facilities. Directions From Savills Summertown office head north on Banbury Road for two miles (heading straight on at one roundabout) and then at the roundabout, take the fourth exit onto Bicester Road. After approximately a mile and a quarter, at the roundabout, take the second exit and continue until you arrive in Islip. Turn right at the junction onto Bletchingdon Road. Continue through the village, passing the Red Lion pub, and you will find the property on your left-hand side, on the corner of Middle Street. -

WIN a ONE NIGHT STAY at the OXFORD MALMAISON | OXFORDSHIRE THAMES PATH | FAMILY FUN Always More to Discover

WIN A ONE NIGHT STAY AT THE OXFORD MALMAISON | OXFORDSHIRE THAMES PATH | FAMILY FUN Always more to discover Tours & Exhibitions | Events | Afternoon Tea Birthplace of Sir Winston Churchill | World Heritage Site BUY ONE DAY, GET 12 MONTHS FREE ATerms precious and conditions apply.time, every time. Britain’sA precious time,Greatest every time.Palace. Britain’s Greatest Palace. www.blenheimpalace.com Contents 4 Oxford by the Locals Get an insight into Oxford from its locals. 8 72 Hours in the Cotswolds The perfect destination for a long weekend away. 12 The Oxfordshire Thames Path Take a walk along the Thames Path and enjoy the most striking riverside scenery in the county. 16 Film & TV Links Find out which famous films and television shows were filmed around the county. 19 Literary Links From Alice in Wonderland to Lord of the Rings, browse literary offerings and connections that Oxfordshire has created. 20 Cherwell the Impressive North See what North Oxfordshire has to offer visitors. 23 Traditions Time your visit to the county to experience at least one of these traditions! 24 Transport Train, coach, bus and airport information. 27 Food and Drink Our top picks of eateries in the county. 29 Shopping Shopping hotspots from around the county. 30 Family Fun Farm parks & wildlife, museums and family tours. 34 Country Houses and Gardens Explore the stories behind the people from country houses and gardens in Oxfordshire. 38 What’s On See what’s on in the county for 2017. 41 Accommodation, Tours Broughton Castle and Attraction Listings Welcome to Oxfordshire Connect with Experience Oxfordshire From the ancient University of Oxford to the rolling hills of the Cotswolds, there is so much rich history and culture for you to explore. -

Romesrecruitsv8.Pdf

"ROME'S RECRUITS" a Hist of PROTESTANTS WHO HAVE BECOME CATHOLICS SINCE THE TRACTARIAN MOVEMENT. Re-printed, with numerous additions and corrections, from " J^HE ^HITEHALL j^EYIEW" Of September 28th, October 5th, 12th, and 19th, 1878. ->♦<- PUBLISHED AT THE OFFICE OF " THE WHITEHALL REVIEW." And Sold by James Parker & Co., 377, Strand, and at Oxford; and by Burns & Oates, Portman Street, W. 1878. PEEFACE. HE publication in four successive numbers of The Whitehall Review of the names of those Protestants who have become Catholics since the Tractarian move ment, led to the almost general suggestion that Rome's Recruits should be permanently embodied in a pamphlet. This has now been done. The lists which appeared in The Whitehall Review have been carefully revised, corrected, and considerably augmented ; and the result is the compilation of what must be regarded as the first List of Converts to Catholicism of a reliable nature. While the idea of issuing such a statement of" Perversions " or " Conversions " was received with unanimous favour — for the silly letter addressed to the Morning Post by Sir Edward Sullivan can only be regarded as the wild effusion of an ultra-Protestant gone very wrong — great curiosity has been manifested as to the sources from whence we derived our information. The modus operandi was very simple. Possessed of a considerable nucleus, our hands were strengthened immediately after the appearance of the first list by 071 XT PREFACE. the co-operation of nearly all the converts themselves, who hastened to beg the addition of their names to the muster-roll. -

Title Page Tag Line 1 Priory Manor 2 Ambrosden a Select Development of 2, 3, 4 & 5 Bedroom Homes in Ambrosden, Oxfordshire a Warm Welcome

TITLE PAGE TAG LINE 1 PRIORY MANOR 2 AMBROSDEN A SELECT DEVELOPMENT OF 2, 3, 4 & 5 BEDROOM HOMES IN AMBROSDEN, OXFORDSHIRE A WARM WELCOME We pride ourselves in providing you with the expert help and advice you may need at all stages of buying a new home, to enable you to bring that dream within your reach. We actively seek regular feedback from our customers once they have moved into a Croudace home and use this information, alongside our own research into lifestyle changes to constantly improve our designs. Environmental aspects are considered both during the construction process and when new homes are in use and are of ever increasing importance. Our homes are designed both to reduce energy demands and minimise their impact on their surroundings. Croudace recognises that the quality of the new homes we build is of vital importance to our customers. Our uncompromising commitment to quality extends to the first class service we offer customers when they have moved in and we have an experienced team dedicated to this task. We are proud of our excellent ratings in independent customer satisfaction surveys, which place us amongst the top echelon in the house building industry. Buying a new home is a big decision. I hope you decide to buy a Croudace home and that you have many happy years living in it. Russell Denness, Group Chief Executive PRIORY MANOR 2 AMBROSDEN A WARM WELCOME FROM CROUDACE HOMES 3 YOUR NEW COMMUNITY Located in the picturesque village of Ambrosden, Priory Manor is a select development of 2, 3, 4 & 5 bedroom homes bordering verdant open countryside with rolling hills leading to the River Cherwell. -

I the Committee of Safety

.· (~. ll II Ii ) ' THE COMMITTEE OF SAFETY. 11 "A thesis submitted to the ,, faculty of the Graduate School of the University of • Minnesota by Etheleen Frances ;emp in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Ii degree of Master of Arts, May 5, 1911. 1;1 I Ii II Ii 11 ' :S I:BLI OGRAPHY. l. Source Material 1. Journals of the House of Lords, vol. V and VI. Journals of the House of Commons, vol. II and III. These contain the greater portion of the material on the Committee of Safety. 2. Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts. London, 1874 etc. These volumes contain here and there a com munication to or from the Committee of Safety but have much less material that might be expected. References found:- 4th Report p 262. 5th Report pp. 48, 54, 56, 63, 65, 69, 80, 107, 114. 7th Report pp. 550-588. 10th Report App. 6 pp. 87-88. 13th Report App. 1 p. 104. 3. Calendar of State Papers. Domestic 1641-1644 London, 1887-8 lla.ny order for military supplies are given in the State Papers but not in full. 4. Rushworth,John, Historical collections, 8 vol. London, 1682-1701. Compilation of declarations and proclamations. Vol. 3 and 7 contain material on the Committee. They contain valuable proclamations of the King which cannot be found elsewhere. 5. Somers, Lord. Tracts, 13 vol. London, 1809-1815. Has several remonstrances of value. ){) 1 ~ ( ' ,.... 6. Whitacre. Diary Add. M S S 31, 116, fol. Had notes from first six months of the Committee period especially.