Archaeological Survey Hear St. Johns, Arizona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zuni Bluehead Sucker BISON No.: 010496

Scientific Name: Catostomus discobolus yarrowi Common Name: Zuni bluehead sucker BISON No.: 010496 Legal Status: ¾ Arizona, Species of ¾ ESA, Proposed ¾ New Mexico-WCA, Special Concern Threatened Threatened ¾ ESA, Endangered ¾ ESA, Threatened ¾ USFS-Region 3, ¾ ESA, Proposed ¾ New Mexico-WCA, Sensitive Endangered Endangered ¾ None Distribution: ¾ Endemic to Arizona ¾ Southern Limit of Range ¾ Endemic to Arizona and ¾ Western Limit of Range New Mexico ¾ Eastern Limit of Range ¾ Endemic to New Mexico ¾ Very Local ¾ Not Restricted to Arizona or New Mexico ¾ Northern Limit of Range Major River Drainages: ¾ Dry Cimmaron River ¾ Rio Yaqui Basin ¾ Canadian River ¾ Wilcox Playa ¾ Southern High Plains ¾ Rio Magdalena Basin ¾ Pecos River ¾ Rio Sonoita Basin ¾ Estancia Basin ¾ Little Colorado River ¾ Tularosa Basin ¾ Mainstream Colorado River ¾ Salt Basin ¾ Virgin River Basin ¾ Rio Grande ¾ Hualapai Lake ¾ Rio Mimbres ¾ Bill Williams Basin ¾ Zuni River ¾ Gila River Status/Trends/Threats (narrative): Federal: FWS Species of concern, USFS Sensitive: Region 3, State AZ: Species of concern, State NM: Endangered. Status The Zuni bluehead sucker was once common in the Little Colorado River and Zuni River drainages, but its historic range has been reduced by approximately 50% (Propst and Hobbs 1996) and its numbers by about 90% in the last 25 years (NMDGF 2000). The Zuni bluehead sucker currently inhabits less then 10% of its probable historic range, and within its current range, its distribution is fragmented, and its status in Arizona is uncertain (Propst 1999). Merkel (1979) reported that on July 21 1971, a sizable population of Zuni Mountain suckers was discovered deep in the Nutria Box where water was flowing. Biologist had assumed that the suckers had been extirpated as a result of fish eradication efforts in the 1960's. -

Final Recovery Plan Southwestern Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax Traillii Extimus)

Final Recovery Plan Southwestern Willow Flycatcher (Empidonax traillii extimus) August 2002 Prepared By Southwestern Willow Flycatcher Recovery Team Technical Subgroup For Region 2 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Albuquerque, New Mexico 87103 Approved: Date: Disclaimer Recovery Plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed to be required to recover and/or protect listed species. Plans are published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, sometimes prepared with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after they have been signed by the Regional Director or Director as approved. Approved Recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. Some of the techniques outlined for recovery efforts in this plan are completely new regarding this subspecies. Therefore, the cost and time estimates are approximations. Citations This document should be cited as follows: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2002. Southwestern Willow Flycatcher Recovery Plan. Albuquerque, New Mexico. i-ix + 210 pp., Appendices A-O Additional copies may be purchased from: Fish and Wildlife Service Reference Service 5430 Governor Lane, Suite 110 Bethesda, Maryland 20814 301/492-6403 or 1-800-582-3421 i This Recovery Plan was prepared by the Southwestern Willow Flycatcher Recovery Team, Technical Subgroup: Deborah M. -

Yanawant: Paiute Places and Landscapes in the Arizona Strip

Yanawant Paiute Places and Landscapes in the Arizona Strip Volume Two OfOfOf The Arizona Strip Landscapes and Place Name Study Prepared by Diane Austin Erin Dean Justin Gaines December 12, 2005 Yanawant Paiute Places and Landscapes in the Arizona Strip Volume Two Of The Arizona Strip Landscapes and Place Name Study Prepared for Bureau of Land Management, Arizona Strip Field Office St. George, Utah Prepared by: Diane Austin Erin Dean Justin Gaines Report of work carried out under contract number #AAA000011TOAAF030023 2 Table of Contents Preface……………………………………………………………………………………………ii i Chapter One: Southern Paiute History on the Arizona Strip………………………………...1 Introduction.............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Early Southern Paiute Contact with Europeans and Euroamericans ........................... 5 1.2 Southern Paiutes and Mormons ........................................................................................ 8 1.3 The Second Powell Expedition......................................................................................... 13 1.4 An Onslaught of Cattle and Further Mormon Expansion............................................ 16 1.5 Interactions in the First Half of the 20 th Century ......................................................... 26 Chapter Two: Southern Paiute Place Names On and Near the Arizona Strip 37 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... -

The Sensualistic Philosophy of the Nineteenth Century

THE SENSUALISTIC PHILOSOPHY THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, CONSIDERED ROBERT L. DABNEY, D.D., LL.D., PROFESSOR IN DIVINITY IN THE UNION THEOLOGICA\. SEMINARY, OF THE PRESBYTER1AH CHURCH OF THB SOUTH PRINCE EDWARD, VA. EDINBURGHl T. & T. CLARK, 38 GEORGE STREET. 1876. CONTENTS. CHAPTER. PAGE. I. THE ISSUE STATED, i II. REVIEW OF THE SENSUALISTIC PHILOSOPHY OF THE PREVIOUS CENTURY. HOBBES, LOCKE, CONDIL- LAC, HELVETIUS, ST. LAMBERT, ... 7 III. ANALYSIS OF THE HUMAN MIND, . .52 IV. SENSUALISTIC ETHICS OF GREAT BRITAIN, . 85 V. POSITIVISM, 93 VI. EVOLUTION THEORY, 107 VII. PHYSIOLOGICAL MATERIALISM, . -131 VIII. SPIRITUALITY OF THE MIND, .... 137 IX. EVOLUTION THEORY MATERIALISTIC, THEREFORE FALSE, 165 X. VALIDITY OF A-PRIORI NOTIONS, . 208 XI. ORIGIIJ OF A-PRIORI NOTIONS, . 245 XII. REFUTATION OF SENSUALISTIC ETHICS, . 287 XIII. PHILOSOPHY OF THE SUPERNATURAL, . 337 .13.15892 SENSUALISTIC PHILOSOPHY. CHAPTER I. THE ISSUE STATED. TT^NGLISHMEN and Americans frequently use the ^ word "sensualist" to describe one in whom the animal appetites are predominant. We shall see that it is a just charge against the Sensualistic philosophy, that it not seldom inclines its advocates to this dominion of beastly lusts. But it is not from this fact that we draw the phrase by which we name it. The Sensualistic philosophy is that theory, which resolves all the powers of the human spirit into the functions of the five senses, and modifications thereof. It is the philosophy which finds all its rudiments in sensation. It not only denies to the spirit of man all innate ideas, but all innate powers of originating ideas, save those given us from our senses. -

TMDL Water Quality Study of the Virgin River Watershed

TMDL Water Quality Study of the Virgin River Watershed DRAFT January 28, 2004 Submitted to: Utah Department of Environmental Quality Division of Water Quality 288 North 1460 West Salt Lake City, UT 84116 Kent Montague Project Manager Harry Lewis Judd Project Supervisor Submitted by: Tetra Tech, Inc. Water Resources and TMDL Center Utah Division of Water Quality TMDL Water Quality Study of the Virgin River CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction.......................................................................................................................................1 2.0 Water Quality Standards ...................................................................................................................5 2.1 303(d) List Status ........................................................................................................................5 2.2 Parameters of Concern.................................................................................................................7 2.2.1 Salinity and Total Dissolved Solids ........................................................................................7 2.2.2 Temperature ............................................................................................................................8 2.2.3 Total Phosphorus and Dissolved Oxygen ...............................................................................8 2.2.4 Selenium..................................................................................................................................8 2.3 Applicable -

Beaver DAM Wash National Conservation

Beaver Dam Wash BLM National Conservation Area What is a National Conservation Area? Through the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009, Congress designated the Beaver Dam Wash National Conservation Area (NCA) in Washington County, Utah “to conserve, protect, and enhance… the ecological, scenic, wildlife, recreational, cultural, historical, natural, educational, and scientific resources” of these public lands. The new NCA comprising roughly of 63,500 acres is managed by the BLM’s St. George Field Office. Where is the Beaver Dam Wash NCA? Located in the southwest corner of Washington County, Utah, the Beaver Dam Wash NCA is approximately 22 miles west of St. George, Utah and roughly 13 miles northwest of Littlefield, Arizona. The Nevada and Arizona state lines, border the western section of the NCA and Interstate 15 and the Virgin River parallel its southern boundary. U.S. Highway 91 is the only paved highway through the NCA. What Are the Special Values of the Beaver Dam Wash NCA? This NCA is within an ecological transition zone between the Mojave Desert and the Great Basin. Creosote bush, white bursage, and other desert shrubs grow at lower elevations and provide habitat for desert bighorn sheep and the Mojave Desert tortoise, a threatened species listed under the Endangered Species Act. Joshua trees and dense stands of blackbrush cover St. George Field Office the slopes of the Beaver Dam Mountains, which rise along the eastern boundary of the NCA. Surface water flows in the upper reaches of Beaver Dam Wash, but rarely travels all the way through the NCA. Riparian vegetation along the stream channel is important habitat for migratory birds and other wildlife. -

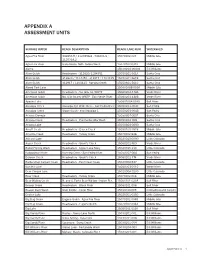

Appendix a Assessment Units

APPENDIX A ASSESSMENT UNITS SURFACE WATER REACH DESCRIPTION REACH/LAKE NUM WATERSHED Agua Fria River 341853.9 / 1120358.6 - 341804.8 / 15070102-023 Middle Gila 1120319.2 Agua Fria River State Route 169 - Yarber Wash 15070102-031B Middle Gila Alamo 15030204-0040A Bill Williams Alum Gulch Headwaters - 312820/1104351 15050301-561A Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312820 / 1104351 - 312917 / 1104425 15050301-561B Santa Cruz Alum Gulch 312917 / 1104425 - Sonoita Creek 15050301-561C Santa Cruz Alvord Park Lake 15060106B-0050 Middle Gila American Gulch Headwaters - No. Gila Co. WWTP 15060203-448A Verde River American Gulch No. Gila County WWTP - East Verde River 15060203-448B Verde River Apache Lake 15060106A-0070 Salt River Aravaipa Creek Aravaipa Cyn Wilderness - San Pedro River 15050203-004C San Pedro Aravaipa Creek Stowe Gulch - end Aravaipa C 15050203-004B San Pedro Arivaca Cienega 15050304-0001 Santa Cruz Arivaca Creek Headwaters - Puertocito/Alta Wash 15050304-008 Santa Cruz Arivaca Lake 15050304-0080 Santa Cruz Arnett Creek Headwaters - Queen Creek 15050100-1818 Middle Gila Arrastra Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-848 Middle Gila Ashurst Lake 15020015-0090 Little Colorado Aspen Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-769 Verde River Babbit Spring Wash Headwaters - Upper Lake Mary 15020015-210 Little Colorado Babocomari River Banning Creek - San Pedro River 15050202-004 San Pedro Bannon Creek Headwaters - Granite Creek 15060202-774 Verde River Barbershop Canyon Creek Headwaters - East Clear Creek 15020008-537 Little Colorado Bartlett Lake 15060203-0110 Verde River Bear Canyon Lake 15020008-0130 Little Colorado Bear Creek Headwaters - Turkey Creek 15070102-046 Middle Gila Bear Wallow Creek N. and S. Forks Bear Wallow - Indian Res. -

Surface Water Supply of the United States 1925 Part Ix, Colobado Eivee Basin

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Ray Lyman Wilbur, Secretary U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY George Otis Smith, Director Water-Supply Paper 609 SURFACE WATER SUPPLY OF THE UNITED STATES 1925 PART IX, COLOBADO EIVEE BASIN NATHAN C. GROVER, Chief Hydraulic Engineer ROBERT POLLANSBEE, A. B. PURTON and W. E, DICKINSON District Engineers Prepared in cooperation with THE STATES OP COLORADO, WYOMING UTAH, CALIFORNIA, and ARIZONA UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT FEINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1929 For saJ<? by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. ----- Price 13 cents CONTENTS Page Authorization and scope of work___________________________________ 1 Definitional terms ______________________________._ 2, Explanation of data_______________________________ 2 Accuracy of field data and computed results_________________________ 4 Publications_____________________________________ 5 Cooperation______________________________________________________ 9 Division of work________________________________________ 9 Gaging-station records..____________________________ 10 Colorado River Basin________________________________ 10 Colorado River and tributaries above Green River___________ 10 Colorado River at Glenwood Springs, Colo_____________ 10 Colorado River near Palisade, Colo________________ 12 Colorado River near Cisco, Utah_______________________ 13 Colorado River at Lees Ferry, Ariz_________________ 15 Colorado River at Bright Angel Creek, near Grand Canyon, Ariz________________________________________ 17 Colorado River near Topock, Ariz__________________ 18 Colorado -

Draft Environmental Assessment for the Designation of Critical Habitat for the Zuni Bluehead Sucker

DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR THE DESIGNATION OF CRITICAL HABITAT FOR THE ZUNI BLUEHEAD SUCKER Prepared by Harris Environmental group, Inc. For the Department of Interior U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service RESPONSIBLE FEDERAL AGENCY: U.S Fish and Wildlife Service CONTACT: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service DATE: March 2015 October 22, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Figures............................................................................................................................................ iv Tables……………………………………………………………………………………………..iv Acronyms ........................................................................................................................................ v CHAPTER 1: PURPOSE OF AND NEED FOR ACTION ........................................................... 8 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 8 Purpose and need for the action .................................................................................................. 8 Proposed action ........................................................................................................................... 9 Background ................................................................................................................................. 9 Critical habitat ............................................................................................................................. 9 Provisions of the ESA ............................................................................................................ -

Diatom Flora of Beaver Dam Creek, Washington County, Utah, USA

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 52 Number 2 Article 3 9-22-1992 Diatom flora of Beaver Dam Creek, Washington County, Utah, USA Kurtis H. Yearsley Brigham Young University Samuel R. Rushforth Brigham Young University Jeffrey R. Johansen John Carroll University, University Heights, Ohio Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Yearsley, Kurtis H.; Rushforth, Samuel R.; and Johansen, Jeffrey R. (1992) "Diatom flora of Beaver Dam Creek, Washington County, Utah, USA," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 52 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol52/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Great Basin Naturalist 52(2), pp 131-138 DIATOM FLORA OF BEAVER DAM CREEK, WASHINGTON COUNTY, UTAH, USA Kurtis H. Yearslel, Samuel R. Rushforth1, and Jeffrey R. Johansen! ABSTRACT.-The diatom flora ofBeaver Dam Creek, Washington County, Utah, was studied. The study area is in awarm MOjave Desert environment at an elevation between 810 and 850 m. A total of 99 taxa were identified from composite samples taken in the fall, winter, spring, and summer seasons. These taxa are all broadly distributed and no endemic species were encountered. Three new records for the state of Utah were identifted: Gomp!umeis eriense Sky. & Mayer, Navicula clginensis var.lata (M. Perag.) Paa., and Nitzschia-calida Grun. The most important taxa throughout the studyas determined by multiplying percent presence by average relative density (Important Species Index) were Cymbella affinM Katz., Epithemia sorex Katz., Navicula veneta Katz . -

Aquatic Habitat Management Program 2020 Utah Accomplishments

U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management AQUATIC HABITAT MANAGEMENT PROGRAM 2020 UTAH ACCOMPLISHMENT REPORTING Photo by: Meghan Krott, Color Country Aquatic Ecologist Page Intentionally Left Blank BLM UTAH Aquatic Habitat Management Program - 2020 Accomplishment Report U.S. Department Of The Interior Bureau Of Land Management Aquatic Habitat Management Program 2020 Utah Accomplishment Reporting The following report is a summary of projects (by District) that maintain and restore fisheries, riparian, water quality, surface and groundwater resources, as well as the physical, chemical, and biological processes of aquatic habitat. These projects would not be possible without the hard work of field staff, as well as the many partnerships that ensure success. Not every project is included, but a variety of projects that fit under the integrated Aquatic Habitat Management (AHM) Program. Compiled by: Justin Jimenez, BLM Utah Aquatics Program Lead 3 BLM UTAH Aquatic Habitat Management Program - 2020 Accomplishment Report Contents Canyon Country District ................................................................................................................. 7 Aquatic Habitats Web App and Other Geospatial Developments ..................................................... 7 Colorado River - Side Channel Restoration Above New Rapid Update .............................................. 8 San Juan River WRI – Side Channel Restoration Updates ................................................................ 12 Erosion Control -

Guardian Agate Sans Family Specimen

Guardian Agate Sans Guardian Agate Sans looks awkward and strange at 18 point, as you can see here. That’s because this family was carefully designed to compensate for the worst imaginable printing conditions: 6 point and below on newsprint. The optical compensations required for maximum legibility under such difficult circumstances inevitably look strange at large sizes. PUBLISHED Stylistically and structurally, Guardian Agate Sans is very much a 2009 part of the Guardian Collection, but it differs in the specifics: A far DESIGNED BY PAUL BARNES & CHRISTIAN SCHWARTZ narrower overall proportion packs a lot of information into a very 40 STYLES small space. Short ascenders and descenders allow for tight, even 2 WEIGHTS W/ ITALICS IN 4 GRADES solid leading without any compromise in redability. Inktraps ensure PLUS 2 ADDITIONAL WEIGHTS W/ ITALICS ALL IN STANDARD AND DUPLEXED VERSIONS that the structures stand up well even at 4pt on newsprint, carving FEATURES out space where ink will fill in and extra clarity is needed. Some GRADED WEIGHTS letters do end up looking admittedly odd at large sizes, such as the DUPLEXED ITALICS DUPLEXED WEIGHTS dropped bars on the f and t, but these compensations ensure that TABULAR LINING FIGURES FRACTIONS the characters remain recognizable no matter what. SUPERSCRIPT/SUBSCRIPT Commercial commercialtype.com Guardian Agate Sans 2 of 15 Guardian Agate Sans Grade 1 Regular Guardian Agate Sans Grade 1 Regular Italic Guardian Agate Sans Grade 1 Bold Guardian Agate Sans Grade 1 Bold Italic Guardian Agate Sans Grade