AZSTRIP Chapter 3.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Editor Hike This Issue Features Ted Snyder, the Quiet Man Who Hikes in Pressed Save Trails Khakis and Leads the CMC Camporees

Carolina Mountain Club November 2012 From The Editor Hike This issue features Ted Snyder, the quiet man who hikes in pressed Save Trails khakis and leads the CMC camporees. He keeps the barbecue and Make Friends sides coming. Like the native plants we see on our hikes, he fits naturally in the woods and is rooted in this area in the best of ways. Don't forget to mark your calendar for the Spring Social (Arboretum Jamboree) for 2013 on April 27 with Ted Snyder conducting our program on the camporees and why they are held. Ted is a mountain In This Issue treasure. He received the CMC Distinguish Service Award. This award is for performing exceptional service during 2012. To see a Ted Snyder short video of Ted leading a hike on the spring 2012 camporee click on the picture below.Ted is the one in the khakis. Also see the camporee CMC Awards schedule for 2013 in this issue. Grand Canyon! Blaze Orange MST Trail Building CMC Stand On MST New State Park Camporees 2013 ATC Mountain Treasures With Ted Snyder Volunteers Needed Sawing If anyone has any articles for the newsletter, send them to me at Opportunity [email protected] Donate To The newsletter will go out the last Friday of every month. The deadline CMC to submit news is the Friday before it goes out. New CMC Council Sincerely, Stars At Kathy Kyle Carolina Mountain Club Annual Dinner CMLC Challenge Quick Links Enewscalendar Future Hikes Hike Reports Photo by Sawako Baiko Ted Snyder --- Patient, Determined Conservationist Interview by Kathy Kyle Ted Snyder received the CMC Distinguish Service Award at the 2012 annual meeting as lead organizer of the camporees that have taken CMC members to areas designated as mountain treasures. -

Grand-Canyon-South-Rim-Map.Pdf

North Rim (see enlargement above) KAIBAB PLATEAU Point Imperial KAIBAB PLATEAU 8803ft Grama Point 2683 m Dragon Head North Rim Bright Angel Vista Encantada Point Sublime 7770 ft Point 7459 ft Tiyo Point Widforss Point Visitor Center 8480ft Confucius Temple 2368m 7900 ft 2585 m 2274 m 7766 ft Grand Canyon Lodge 7081 ft Shiva Temple 2367 m 2403 m Obi Point Chuar Butte Buddha Temple 6394ft Colorado River 2159 m 7570 ft 7928 ft Cape Solitude Little 2308m 7204 ft 2417 m Francois Matthes Point WALHALLA PLATEAU 1949m HINDU 2196 m 8020 ft 6144ft 2445 m 1873m AMPHITHEATER N Cape Final Temple of Osiris YO Temple of Ra Isis Temple N 7916ft From 6637 ft CA Temple Butte 6078 ft 7014 ft L 2413 m Lake 1853 m 2023 m 2138 m Hillers Butte GE Walhalla Overlook 5308ft Powell T N Brahma Temple 7998ft Jupiter Temple 1618m ri 5885 ft A ni T 7851ft Thor Temple ty H 2438 m 7081ft GR 1794 m G 2302 m 6741 ft ANIT I 2158 m E C R Cape Royal PALISADES OF GO r B Zoroaster Temple 2055m RG e k 7865 ft E Tower of Set e ee 7129 ft Venus Temple THE DESERT To k r C 2398 m 6257ft Lake 6026 ft Cheops Pyramid l 2173 m N Pha e Freya Castle Espejo Butte g O 1907 m Mead 1837m 5399 ft nto n m A Y t 7299 ft 1646m C N reek gh Sumner Butte Wotans Throne 2225m Apollo Temple i A Br OTTOMAN 5156 ft C 7633 ft 1572 m AMPHITHEATER 2327 m 2546 ft R E Cocopa Point 768 m T Angels Vishnu Temple Comanche Point M S Co TONTO PLATFOR 6800 ft Phantom Ranch Gate 7829 ft 7073ft lor 2073 m A ado O 2386 m 2156m R Yuma Point Riv Hopi ek er O e 6646 ft Z r Pima Mohave Point Maricopa C Krishna Shrine T -

Grand Canyon National Park U.S

National Park Service Grand Canyon National Park U.S. Department of the Interior The official newspaper North Rim 2015 Season The Guide North Rim Information and Maps Roosevelt Point, named for President Theodore Roosevelt who in 1908, declared Grand Canyon a national monument. Grand Canyon was later established as a national park in 1919 by President Woodrow Wilson. Welcome to Grand Canyon S ITTING ATOP THE K AIBAB a meadow, a mother turkey leading her thunderstorms, comes and goes all too flies from the South Rim, the North Plateau, 8,000 to 9,000 feet (2,400– young across the road, or a mountain quickly, only to give way to the colors Rim offers a very different visitor 2,750 m) above sea level with lush lion slinking off into the cover of the of fall. With the yellows and oranges of experience. Solitude, awe-inspiring green meadows surrounded by a mixed forest. Visitors in the spring may see quaking aspen and the reds of Rocky views, a slower pace, and the feeling of conifer forest sprinkled with white- remnants of winter in disappearing Mountain maple, the forest seems to going back in time are only a few of the barked aspen, the North Rim is an oasis snowdrifts or temporary mountain glow. Crispness in the air warns of winter many attributes the North Rim has in the desert. Here you may observe lakes of melted snow. The summer, snowstorms soon to come. Although to offer. Discover the uniqueness of deer feeding, a coyote chasing mice in with colorful wildflowers and intense only 10 miles (16 km) as the raven Grand Canyon’s North Rim. -

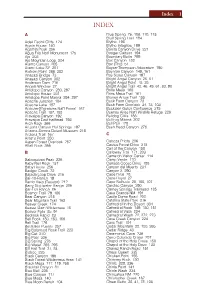

Index 1 INDEX

Index 1 INDEX A Blue Spring 76, 106, 110, 115 Bluff Spring Trail 184 Adeii Eechii Cliffs 124 Blythe 198 Agate House 140 Blythe Intaglios 199 Agathla Peak 256 Bonita Canyon Drive 221 Agua Fria Nat'l Monument 175 Booger Canyon 194 Ajo 203 Boundary Butte 299 Ajo Mountain Loop 204 Box Canyon 132 Alamo Canyon 205 Box (The) 51 Alamo Lake SP 201 Boyce-Thompson Arboretum 190 Alstrom Point 266, 302 Boynton Canyon 149, 161 Anasazi Bridge 73 Boy Scout Canyon 197 Anasazi Canyon 302 Bright Angel Canyon 25, 51 Anderson Dam 216 Bright Angel Point 15, 25 Angels Window 27 Bright Angel Trail 42, 46, 49, 61, 80, 90 Antelope Canyon 280, 297 Brins Mesa 160 Antelope House 231 Brins Mesa Trail 161 Antelope Point Marina 294, 297 Broken Arrow Trail 155 Apache Junction 184 Buck Farm Canyon 73 Apache Lake 187 Buck Farm Overlook 34, 73, 103 Apache-Sitgreaves Nat'l Forest 167 Buckskin Gulch Confluence 275 Apache Trail 187, 188 Buenos Aires Nat'l Wildlife Refuge 226 Aravaipa Canyon 192 Bulldog Cliffs 186 Aravaipa East trailhead 193 Bullfrog Marina 302 Arch Rock 366 Bull Pen 170 Arizona Canyon Hot Springs 197 Bush Head Canyon 278 Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum 216 Arizona Trail 167 C Artist's Point 250 Aspen Forest Overlook 257 Cabeza Prieta 206 Atlatl Rock 366 Cactus Forest Drive 218 Call of the Canyon 158 B Calloway Trail 171, 203 Cameron Visitor Center 114 Baboquivari Peak 226 Camp Verde 170 Baby Bell Rock 157 Canada Goose Drive 198 Baby Rocks 256 Canyon del Muerto 231 Badger Creek 72 Canyon X 290 Bajada Loop Drive 216 Cape Final 28 Bar-10-Ranch 19 Cape Royal 27 Barrio -

I2628 Pamphlet

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP I–2628 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Version 1.0 GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE LITTLEFIELD 30' × 60' QUADRANGLE, MOHAVE COUNTY, NORTHWESTERN ARIZONA By George H. Billingsley and Jeremiah B. Workman INTRODUCTION 10 km north of the north-central part of the map and are the largest settlements near the map area. This map is one result of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Interstate Highway 15 and U.S. Highway 91 provide intent to provide geologic map coverage and a better under- access to the northwest corner of the map area, and Arizona standing of the transition in regional geology between the State Highway 389 provides access to the northeast corner. Basin and Range and Colorado Plateaus in southeastern Ne- Access to the rest of the map area is by dirt roads maintained vada, southwestern Utah, and northwestern Arizona. Infor- by the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, Arizona Strip Dis- mation gained from this regional study provides a better trict, St. George, Utah. The area is largely managed by the understanding of the tectonic and magmatic evolution of an U.S. Bureau of Land Management, the Arizona Strip Dis- area of extreme contrasts in late Mesozoic-early Tertiary trict, which includes sections of land controlled by the State compression, Cenozoic magmatism, and Cenozoic extension. of Arizona. There are several isolated sections of privately This map is a synthesis of 32 new geologic maps encom- owned lands, mainly near the communities of Littlefield, passing the Littlefield 30' x 60' quadrangle, Arizona. Geo- Beaver Dam, and Colorado City. -

Yanawant: Paiute Places and Landscapes in the Arizona Strip

Yanawant Paiute Places and Landscapes in the Arizona Strip Volume Two OfOfOf The Arizona Strip Landscapes and Place Name Study Prepared by Diane Austin Erin Dean Justin Gaines December 12, 2005 Yanawant Paiute Places and Landscapes in the Arizona Strip Volume Two Of The Arizona Strip Landscapes and Place Name Study Prepared for Bureau of Land Management, Arizona Strip Field Office St. George, Utah Prepared by: Diane Austin Erin Dean Justin Gaines Report of work carried out under contract number #AAA000011TOAAF030023 2 Table of Contents Preface……………………………………………………………………………………………ii i Chapter One: Southern Paiute History on the Arizona Strip………………………………...1 Introduction.............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Early Southern Paiute Contact with Europeans and Euroamericans ........................... 5 1.2 Southern Paiutes and Mormons ........................................................................................ 8 1.3 The Second Powell Expedition......................................................................................... 13 1.4 An Onslaught of Cattle and Further Mormon Expansion............................................ 16 1.5 Interactions in the First Half of the 20 th Century ......................................................... 26 Chapter Two: Southern Paiute Place Names On and Near the Arizona Strip 37 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... -

TMDL Water Quality Study of the Virgin River Watershed

TMDL Water Quality Study of the Virgin River Watershed DRAFT January 28, 2004 Submitted to: Utah Department of Environmental Quality Division of Water Quality 288 North 1460 West Salt Lake City, UT 84116 Kent Montague Project Manager Harry Lewis Judd Project Supervisor Submitted by: Tetra Tech, Inc. Water Resources and TMDL Center Utah Division of Water Quality TMDL Water Quality Study of the Virgin River CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction.......................................................................................................................................1 2.0 Water Quality Standards ...................................................................................................................5 2.1 303(d) List Status ........................................................................................................................5 2.2 Parameters of Concern.................................................................................................................7 2.2.1 Salinity and Total Dissolved Solids ........................................................................................7 2.2.2 Temperature ............................................................................................................................8 2.2.3 Total Phosphorus and Dissolved Oxygen ...............................................................................8 2.2.4 Selenium..................................................................................................................................8 2.3 Applicable -

Demise of the Dams: the Construction, Destruction, and Legacy of Late Cenozoic Volcanism in the Western Grand Canyon

CHAPTER 7: DEMISE OF THE DAMS: THE CONSTRUCTION, DESTRUCTION, AND LEGACY OF LATE CENOZOIC VOLCANISM IN THE WESTERN GRAND CANYON "We have no difficulty as we float along, and I am able to observe the wonderful phenomena connected with this flood of lava. The canyon was doubtless filled to a height of 1,200 to 1,500 feet, perhaps by more than one flood. This would dam the water back, and in cutting through this great lava bed, a new channel has been formed, sometimes on one side, sometimes on the other . What a conflict of water and fire there must have been here! Just imagine a river of molten rock running down a river of melted snow. What a seething and boiling of waters, what clouds of steam rolled into the heavens!" John Wesley Powell, August 25, 1869 ALISHA N. CLARK INTRODUCTION Volcanic episodes have occurred periodically throughout the history of the Grand Canyon (e.g. Garber, this volume; Bennett, this volume). During certain phases of the tectonic evolution of the Grand Canyon, uplift of the Colorado Plateau lead to an extensional tectonic environment that thinned the Earth’s crust facilitating transport of magmatic material to the Earth’s surface, often along fault zones that acted as conduits for the basaltic magma generated in the mantle below (see Bennett, this volume for discussion of regional tectonics). There are three volcanic fields on the western Grand Canyon: the Grand Wash, Shivwits Plateau, and UinKaret Plateau, from west to east, respectively. The youngest of these, the UinKaret Plateau, was active during the Pleistocene (Crow et al., 2008; Dalrymple and Hamblin, 1998; Hamblin, 1994). -

Alkalic-Type Epithermal Gold Deposit Model

Alkalic-Type Epithermal Gold Deposit Model Chapter R of Mineral Deposit Models for Resource Assessment Scientific Investigations Report 2010–5070–R U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Photographs of alkalic-type epithermal gold deposits and ores. Upper left: Cripple Creek, Colorado—One of the largest alkalic-type epithermal gold deposits in the world showing the Cresson open pit looking southwest. Note the green funnel-shaped area along the pit wall is lamprophyre of the Cresson Pipe, a common alkaline rock type in these deposits. The Cresson Pipe was mined by historic underground methods and produced some of the richest ores in the district. The holes that are visible along several benches in the pit (bottom portion of photograph) are historic underground mine levels. (Photograph by Karen Kelley, USGS, April, 2002). Upper right: High-grade gold ore from the Porgera deposit in Papua New Guinea showing native gold intergrown with gold-silver telluride minerals (silvery) and pyrite. (Photograph by Jeremy Richards, University of Alberta, Canada, 2013, used with permission). Lower left: Mayflower Mine, Montana—High-grade hessite, petzite, benleonardite, and coloradoite in limestone. (Photograph by Paul Spry, Iowa State University, 1995, used with permission). Lower right: View of north rim of Navilawa Caldera, which hosts the Banana Creek prospect, Fiji, from the portal of the Tuvatu prospect. (Photograph by Paul Spry, Iowa State University, 2007, used with permission). Alkalic-Type Epithermal Gold Deposit Model By Karen D. Kelley, Paul G. Spry, Virginia T. McLemore, David L. Fey, and Eric D. Anderson Chapter R of Mineral Deposit Models for Resource Assessment Scientific Investigations Report 2010–5070–R U.S. -

North Kaibab Ranger District Travel Management Project Environmental Assessment

Environmental Assessment United States Department of Agriculture North Kaibab Ranger District Forest Service Travel Management Project Southwestern Region September 2012 Kaibab National Forest Coconino and Mohave Counties, Arizona Information Contact: Wade Christy / Recreation & Lands Kaibab National Forest - NKRD Mail: P.O.Box 248 / 430 S. Main St. Fredonia, AZ 86022 Phone: 928-643-8135 E-mail: [email protected] It is the mission of the USDA Forest Service to sustain the health, diversity, and productivity of the Nation’s forests and grasslands to meet the needs of present and future generations. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Printed on recycled paper – September -

Subduction Cycles Under Western North America During the Mesozoic and Cenozoic Eras

.. Geological Society of America Special Paper 299 1995 Subduction cycles under western North America during the Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras Peter L. Ward U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefield Road, MS 977, Menlo Park, California 94025 ABSTRACT An extensive review of geologic and tectonic features of western North America suggests that the interaction of oceanic plates with the continent follows a broad cycli- cal pattern. In a typical cycle, periods of rapid subduction (7-15 cdyr), andesitic vol- canism, and trench-normal contraction are followed by a shift to trench-normal extension, the onset of voluminous silicic volcanism, formation of large calderas, and the creation of major batholiths. Extension becomes pervasive in metamorphic core complexes, and there is a shift to fundamentally basaltic volcanism, formation of flood basalts, widespread rifting, rotation of terranes, and extensive circulation of flu- ids throughout the plate margin. Strike-slip faulting becomes widespread with the creation of new tectonostratigraphic terranes. A new subduction zone forms and the cycle repeats. Each cycle is 50-80 m.y. long; cycles since the Triassic have ended and begun at approximately 225, 152, 92, 44, and 15 Ma. The youngest two cycles are diachronous, one from Oregon to Alaska, the other from central Mexico to Califor- nia. The transitions from one cycle to the next cycle are characterized by rapid and pervasive changes termed, in this chapter, “major chaotic tectonic events.” These events appear to be related to the necking or breaking apart of the formerly sub- ducted slab at shallow depth, the resulting delamination of the plate margin, and the onset of a new subduction cycle. -

4310-32-P Department of The

4310-32-P DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Bureau of Land Management Notice of Proposed Withdrawal and Opportunity for Public Meeting; Arizona AGENCY: Bureau of Land Management, Interior. ACTION: Notice. SUMMARY: The Secretary of the Interior proposes to withdraw approximately 633,547 acres of public lands and 360,002 acres of National Forest System lands for up to 20 years from location and entry under the Mining Law of 1872, 30 U.S.C. §§ 22 et seq., on behalf of the Bureau of Land Management and the United States Forest Service. The purpose of the withdrawal, if determined to be appropriate, would be to protect the Grand Canyon watershed from adverse effects of locatable hardrock mineral exploration and mining. This notice segregates the lands from location and entry under the 1872 Mining Law for up to 2 years to allow time for various studies and analyses, including appropriate National Environmental Policy Act analysis. These actions will support a final decision on whether or not to proceed with a withdrawal. The lands will remain open to the mineral leasing, geothermal leasing, mineral materials, and public land laws. DATES: Comments and requests for a public meeting must be received by (insert date 90 days after date of publication in the FEDERAL REGISTER). ADDRESSES: Comments and meeting requests should be sent to the District Manager, Bureau of Land Management, Arizona Strip District Office, 345 East Riverside Drive, St. George, Utah 84790-9000, or Forest Supervisor, Forest Service, Kaibab National Forest, 800 South Sixth St., Williams, Arizona 86046. 2 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Scott Florence, District Manager, BLM Arizona Strip District, 435-688-3200, or Michael Williams, Forest Supervisor, Kaibab National Forest, 928-635-8200.