Sir Rowland Winn and No. 11 St James's Square, London, 1766–1787

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LAF out & About, in Linton in the Yorkshire Dales

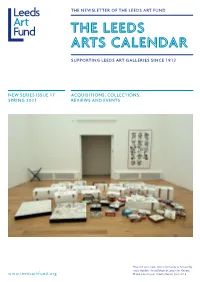

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE LEEDS ART FUND SUPPORTING LEEDS ART GALLERIES SINCE 1912 NEW SERIES ISSUE 17 ACQUISITIONS, COLLECTIONS, SPRING 2021 REVIEWS AND EVENTS How the Artist was led to the Study of Nature by Andy Holden - Installation at Leeds Art Gallery. www.leedsartfund.org Photo Courtesy of Simon Warner, June 2018. RECENT ACQUISITION IMPORTANT DRAWINGS BY THOMAS CHIPPENDALE SENIOR AND JUNIOR The Chippendale Society has recently acquired six previously unknown drawings attributed to Thomas Chippendale senior and junior. The key to their attribution is provided by a drawing for a lantern pedestal, which is the design drawing for a set of six supplied by Chippendale to Harewood House in 1774. The drawings are by two different hands. Two are thought to date from about 1760 and are typical of Thomas Chippendale senior’s free-flowing style with its use of delicate washes to suggest shadow and perspective. The other four are by a different hand and can confidently be attributed to Thomas Chippendale junior (the first to be discovered) on the basis of strong similarities with his engravings published in 1779. These are the first Chippendale drawings of any kind in the fully mature neo-Classical style of the 1770s. Chippendale junior was first recorded as active in his father’s firm in 1766, aged 17, and his first signed drawing is of a neo-Classical tablet, dated 1772. However, it has long been assumed that he did not assume a significant role until c.1775-6. The new drawings demonstrate that Chippendale junior was involved much earlier than previously thought. -

Fine English Furniture & Works Of

Bonhams 101 New Bond Street London W1S 1SR +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 +44 (0) 20 7447 7400 fax 20741 Fine English Furniture & Works of Art, of Works Fine English Furniture & 6 March 2013, New Bond Street, London Bond Street, New 6 March 2013, Fine English Furniture & Works of Art Wednesday 6 March 2013 at 2pm New Bond Street, London Fine English Furniture & Works of Art Wednesday 6 March 2013 at 2pm New Bond Street, London Bonhams Enquiries Customer Services 101 New Bond Street [email protected] Monday to Friday 8.30am to 6pm London W1S 1SR +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 www.bonhams.com Furniture & Works of Art Guy Savill Please see back of catalogue Viewing +44 (0) 8700 273 604 for important notice to bidders Sunday 3 March 11am to 3pm [email protected] Monday 4 March 9am to 4.30pm Illustrations Tuesday 5 March 9am to 4.30pm Sally Stratton Front cover: Lot 20 Wednesday 6 March 9am to 12pm +44 (0) 8700 273 603 Back cover: Lot 18 [email protected] Inside front cover: Lot 285 (detail) Bids Inside back cover: Lot 285 (detail) +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 Sculpture 20741 +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax Rachael Osborn-Howard Sale Number: To bid via the internet please visit +44 (0) 8700 273 610 £20 (£25 by post) www.bonhams.com [email protected] Catalogue: Please provide details of the lots Administrator Live online bidding is on which you wish to place bids Jackie Brown available for this sale at least 24 hours prior to the sale. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STRFFT AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 . 737-4215/842-6353 Revised: July 1985 EXHIBITION FACT SHEET Title: THE TREASURE HOUSES OF BRITAIN: FIVE HUNDRED YEARS OF PRIVATE PATRONAGE AND ART COLLECTING Patrons; Their Royal Highnesses The Prince and Princess of Wales Dates: November 3, 1985 through March. 16, 1986. (This exhibition will not travel. Most loans from houses open to view are expected to remain in place until the late suitmer of 1985 and to be returned before many of the houses open for their visitors in the spring of 1986.) Credits: This exhibition is made possible by a generous grant from the Ford Motor Company. The exhibition was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, in collaboration with the British Council and is supported by indemnities from Her Majesty's Treasury and the U.S. Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities. Further British assistance was supplied by the National Trust and the Historic Houses Association. British Airways has been designated the official carrier of the exhibition. History of the exhibition; The idea that the National Gallery of Art consider holding a major exhibition devoted to British art evolved in discussions with the British Council in 1979. J. Carter Brown, Director of the National Gallery of Art, proposed an exhibition on the British country house as a "vessel of civilization," bringing together works of art illustrating the extraordinary achievement of collecting and patronage throughout Britain over the past five hundred years. As this concept carried with it the additional, contemporary advantage of stimulating greater interest in and support of those houses open to public viewing, it was enthusiastically endorsed by the late Lord Howard of Henderskelfe, then-Chairman of the Historic Houses Association, Julian Andrews, Director of the Fine Arts Department of the British Council, and Lord Gibson, Chairman of the National Trust. -

Christie's London Presents: Celebrating the Genius of Chippendale's Designs & the Perfection of His Execution 5 July 2

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 23 MAY 2018 Christie’s London Presents: Celebrating the Genius of Chippendale’s Designs & the Perfection of His Execution 5 July 2018 ‘The Shakespeare of English Furniture makers’ Christopher Gilbert London – On 5 July, Christie’s landmark sale Thomas Chippendale 300 Years will celebrate the genius of Chippendale’s designs and the perfection of his execution, in the 300th anniversary year of his birth. Taking place during Christie’s Classic Week, the dedicated London auction will present 22 lots with estimates ranging from £5,000 to £5 million. A selection of works will be on public view at Christie’s London headquarters until 25 May, with the full pre-sale exhibition opening from 30 June to 5 July. Collectively, the sale encompasses some of the grandest pieces of 18th century furniture ever created, including Sir Rowland Winn’s Commode (estimate: £3-5million) and The Dundas Sofas (each sofa with an estimate of £2-3million). Remembered as ‘The Shakespeare of English Furniture makers’, Chippendale was the master of many mediums. This is highlighted by the breadth of works being offered, including his game-changing book which made his name The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director, first published in 1754, which astutely promoted his designs to the most affluent potential clients of the day (the expanded 1762 3rd edition, estimate: £5,000-8,000) alongside works executed in giltwood, mahogany, marquetry and lacquer. Orlando Rock, Christie’s UK Chairman and Co Chairman of Decorative Arts: “This auction will present arguably the greatest neo-classical masterpieces by Thomas Chippendale that will ever come to market, providing unique opportunities to buy the very best at comparatively accessible price levels. -

THOMAS CHIPPENDALE at DUMFRIES HOUSE Work Proceeded; the Following Extract Concerns the Speci- Will Not Be Well Understood by a Small Drawing

CHRISTOPHER GILBERT Thomas Chippendaleat Dumfries House* THEpublication in I 754 of Thomas Chippendale'scelebrated the furniture he supplied during the mid-i 760's to Sir volume of designs The Gentlemanand Cabinet-Maker'sDirector Rowland Winn of Nostell Priory' and Sir Lawrence Dundas8 is generally assumed to have exercised a dramatically included pieces which reflect his early artistic ideals, they stimulating effect on his trade for it was reprinted the are seldom intimately related to plates in the Directorand following year, revised and enlarged in 1762 and all his after 1765 he rapidly assimilated the neo-classical style known commissions date from after its appearance. While formulated by Robert Adam. In fact the impressive amount there is no doubt that the volume was widely circulated and of documented Chippendale furniture dating from the time most influential surprisingly little furniture made by the when he subscribed to Adam's criteria of taste has en- author's own firm during the decade immediately following couraged the belief amongst experts that this was his 'best' its publication has been traced - there is at present evidence period - a view not shared by the present author. of only six commissions compared with twenty-six during Although the Earl of Dumfries is recorded as a patron in the remaining fifteen years of his life. Of these six the Earl the third edition of Chippendale'sDirector9 and the existence of Morton is merely named as a patron in one of the prefatory of relevant bills has been known for over fifty years'0 this notes to the third edition of the Director.'Two others, James notable collection has never been discussed in detail. -

Robert Adam's Revolution in Architecture Miranda Jane Routh Hausberg University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture Miranda Jane Routh Hausberg University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Hausberg, Miranda Jane Routh, "Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3339. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3339 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3339 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture Abstract ABSTRACT ROBERT ADAM’S REVOLUTION IN ARCHITECTURE Robert Adam (1728-92) was a revolutionary artist and, unusually, he possessed the insight and bravado to self-identify as one publicly. In the first fascicle of his three-volume Works in Architecture of Robert and James Adam (published in installments between 1773 and 1822), he proclaimed that he had started a “revolution” in the art of architecture. Adam’s “revolution” was expansive: it comprised the introduction of avant-garde, light, and elegant architectural decoration; mastery in the design of picturesque and scenographic interiors; and a revision of Renaissance traditions, including the relegation of architectural orders, the rejection of most Palladian forms, and the embrace of the concept of taste as a foundation of architecture. -

David Garrick at the Adelphi

DAVID GARRICK AT THE ADELPHI BY SAMUEL J. ROGAL Dr. Rogal is an associate professor of English at the State University of New York at Oswego. Rutgers Library houses several of Garrick's "altered" versions of the works of English playwrights in addition to his own plays. N 20 JANUARY 1779, at No. 5 Royal Terrace, the Adel- phi, David Garrick died. Four months later, Saturday, 24 OApril 1779, Dr. Johnson remarked to James Boswell, "Gar- rick was a very good man, the cheerfullest man of his age; a decent liver in a profession which is supposed to give indulgence to licen- tiousness; and a man who gave away, freely, money acquired by himself. He began the world with a great hunger for money; the son of a half-pay officer, bred in a family whose study was to make four-pence do as much as others made four-pence halfpenny do. But when he had got money, he was very liberal."1 Perhaps the best oc- casions upon which to examine the actor-manager's financial liberal- ity are first his occupancy of No. 5 (later numbered "4") Royal Ter- race and second his dealings with the outfitter of this residence, Thomas Chippendale (1718-1779)—the celebrated cabinetmaker, designer, and decorator. In July 1749, the initial year of his marriage to Eva Marie Veigel (1724-1822), Garrick purchased the first of his three residences— a house at No. 27 Southampton Street, London; the couple assumed occupancy on 14 October.2 Four and one-half years later (January 1754), he leased—and then purchased on 30 August—the Fuller House in Hampton, which Mrs. -

Newsletter 213 February 2019

The Furniture History Society Newsletter 213 February 2019 In this issue: A Contemporary Commission: The Schiele Chair | Society News | A Tribute | Research | Future Society Events | Occasional and Overseas Visits | Other Notices | Book Review | Reports on the Society’s Events | Publications | Grants A Contemporary Commission: The Schiele Chair he Schiele Chair , made by Dublin-based The brief to Rod (b. 1950 ) and Alison Wales T craftsman Colin Harris (b. 1972 ), is one (b. 1952 ) was to create this piece of of the most recent additions to the furniture to echo the existing Renaissance Goodison gift of contemporary British cassoni in the Fitzwilliam’s collection. The crafts to the Fitzwilliam Museum, resulting fumed and limed oak chest with University of Cambridge. 1 stainless steel inlay is partly painted red It is one of several pieces of furniture in and blue, inspired by the saturated colours the collection commissioned from leading of the museum’s Italian Renaissance British designers/makers. Collectively, religious painting, especially the these pieces demonstrate the quality of traditional red dress and blue mantle of work undertaken by these makers over the the Virgin Mary. Rod and Alison Wales last thirty years, an achievement that has share a history with Colin Harris (the not received the attention of many maker of The Schiele Chair ) in that all three commentators or furniture historians. The studied/worked at Parnham College, museum hopes to be a centre for studies in founded by John Makepeace. 6 the field, encouraging the interest of Makepeace opened Parnham College visitors and the involvement of makers. (originally, The School for Craftsmen in It is the latest in a series of furniture Wood) on 19 September 1977 , in what had commissions. -

" a Waste of Good Wood"? Gillows and Their Furniture, 1760-1800

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON 'A WASTE OF GOOD WOOD'? GILLOWS AND THEIR FURNITURE, 1760-1800 IN TWO VOLUMES VOLUME ONE ELEANOR MARY QUINCE DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY CENTRE FOR STUDIES IN ARCHITECTURE AND URBANISM SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES SEPTEMBER 2003 The candidate confirms that this is the result of work done wholly while she was in registered postgraduate candidature. She also confirms that this is her own work and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. ERRATA E. M. Quince, Doctor of Philosophy, September 2003 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT CENTRE FOR STUDIES IN ARCHITECTURE AND URBANISM SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES Doctor of Philosophy 'A WASTE OF GOOD WOOD'? GILLOWS AND THEIR FURNITURE, 1760-1800 By Eleanor Mary Quince This study asks a question of three bodies of material: who were Gillows? As a furniture-making firm, working between 1760 and 1800, Gillows have been recorded within furniture history, within a biography by historian Lindsay Boynton and within their own records, their autobiography. Furniture history is viewed within this thesis as a construction, a history that both includes and excludes. Roland Barthes' exercise in the semiology of fashion. The Fashion System, is used as a means of viewing the taxonomic system of classification that the furniture historians have employed to categorise old English furniture. I assert that this, the furniture system, has sought to use style, age and author to determine the nature of eighteenth-century furniture. A discussion of how Gillows have been viewed by the furniture historians provides an image of the firm as provincial, middle class makers, followers rather than leaders in the field of eighteenth-century furniture design. -

Newsletter 210 May 2018

The Furniture History Society Newsletter 210 May 2018 In this issue: Chippendale 2018 : A Curatorial Memoir | Future Society Events | Occasional and Overseas Visits | Other Notices | Book Reviews | Reports on the Society’s Events | Publications | Grants Chippendale 2018: A Curatorial Memoir ike most organizations dedicated to the with substantial funding from the Heritage L memory of a great person, the Lottery Fund. We therefore made an Chippendale Society has often used informal approach to the Yorkshire HLF to anniversaries to promote its cause. The discuss a similar strategy. It soon became Society was in its infancy in 1968 at the clear, however, that the Society lacked the time of the 250 th anniversary of capacity to facilitate anything so ambitious, Chippendale senior’s birth, but keenly despite the resources which the HLF might endorsed the exhibition Thomas Chippendale provide. At the same time, it was noted that and his Patrons in the North with a number the HLF has never been an enthusiastic of commemorative events. Ten years later, promoter of temporary exhibitions. in 1979 , its newly formed collection of Somewhat dejected we reconsidered the drawings made an important contribution options and, undeterred, we began a series to the exhibition marking the bicentenary of informal conversations with other of his death, held at Temple Newsam, like interested parties, particularly, at this the earlier one. Again, in 2004 , the Society stage, with Nostell Priory. A meeting was marked the quarter millennium of the first convened there in March 2016 , with edition of the Director by publishing a invitations sent to representatives from facsimile reprint of its own rare copy. -

Account: Thomas Chippendale at No.11 St James's Square, London

This is a repository copy of Recovering a ‘lost’ account: Thomas Chippendale at No.11 St James’s Square, London. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/131945/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Bristol, KAC (2018) Recovering a ‘lost’ account: Thomas Chippendale at No.11 St James’s Square, London. Furniture History, 54. ISSN 0016-3058 This article is protected b copyright. All rights reserved. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Furniture History. Uploaded with permission from the Furniture History Society. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Recovering a ‘lost’ account: Thomas Chippendale at No.11 St James’s Square, London Nostell, West Yorkshire, is widely recognised as one of the best documented of Thomas Chippendale’s commissions and a significant number of identifiable pieces from his workshop remain in the house today; however, his work at the Winn family’s London townhouse has been a gaping lacuna, perhaps because their residency came to an abrupt end when Sir Rowland Winn was killed in a coaching accident in 1785, the house was sold to meet his outstanding debts, and the contents were auctioned off by James Christie. -

Fall 2018 Royal Oak Calendar 9 Cartier Mansion Tour | the Current Season of Our Drue Heinz Lecture Series Began on September 24 with Nina New York, NY 5:15 P.M

Americans in Alliance with the National Trust of England, Wales, and Northern Ireland Focus on Buckinghamshire Celebrating Chippendale The Country House During World War I British Foodways Over the Centuries FALL/WINTER 2018 2 | From the Executive Director THE ROYAL OAK FOUNDATION 20 West 44th Street, Suite 606 New York, New York 10036-6603 Dear Members & Friends, 212.480.2889 | www.royal-oak.org Anniversaries are about Oddy. They help to provide perspective BOARD OF DIRECTORS on some of the long-term institutional remembering, recognition Chairman and renewal. relationships, such as those with the Lynne L. Rickabaugh Attingham Summer School. A few Vice Chairman As Royal Oak moves into the final months former Board members have joined with Prof. Susan S. Samuelson of its 45th Anniversary year, we have lots some current Board members to help Treasurer to remember. It was actually in October form the 45th Anniversary benefit event Renee Nichols Tucei 1973, as a newly established Host Committee. This Secretary foundation waiting for its Thomas M. Kelly celebration is intended tax-exempt status, that the Directors to bring old and new National Trust provided Betsy Shack Barbanell friends together to for our first three years Michael A. Boyd congratulate each other of funding—they were Prof. Sir David Cannadine on what they have our angel investors—and Constance M. Cincotta accomplished on behalf allowed Royal Oak to John Southerton Clark communicate with the of the National Trust. Robert C. Daum 3,000 Trust members living Tracey A. Dedrick We have also renewed in the United States. From Anne Blackwell Ervin the commitment to those valuable acorns Pamela K.