David Garrick at the Adelphi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Seven Deadly SINS

The Seven Deadly SINS BERNARD QUARITCH LTD Index to the Sins Lust Items 1-14 Greed and Gluttony Items 15-23 Sloth Items 24-31 Wrath Items 32-40 Pride and Envy Items 41-51 All Seven Sins Item 52 See final page for payment details. I LUST THE STATISTICS OF DEBAUCHERY 1) [BARNAUD, Nicolas]. Le Cabinet du Roy de France, dans lequel il y a trois perles precieuses d’inestimable valeur: par le moyen desquelles sa Majesté s’en va le premier monarque du monde, & ses sujets du tout soulagez. [No place or printer], 1581. 8vo, pp. [xvi], 647, [11], [2, blank]; lightly browned or spotted in places, the final 6 leaves with small wormholes at inner margins; a very good copy in contemporary vellum with yapp edges; from the library of the Princes of Liechtenstein, with armorial bookplate on front paste- down. £2200 First edition, first issue, of this harsh criticism of the debauched church and rotten nobility and the resulting bad finances of France, anonymously published by a well-travelled Protestant physician, and writer on alchemy who was to become an associate of the reformer Fausto Paolo Sozzini, better known as Socinus, the founder of the reformist school influential in Poland. Barnaud was accused of atheism and excommunicated in 1604. He is one of the real historical figures, on which the Doctor Faustus legend is based. This ‘violent pamphlet against the clergy (translated from Dictionnaire de biographie française) is divided into three books, symbolized by pearls, as mentioned in the title. In the first book Barnaud gives an account and precise numbers of sodomites, illegitimate children, prostitutes etc. -

The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D.," Appeared in 1791

•Y»] Y Y T 'Y Y Y Qtis>\% Wn^. ECLECTIC ENGLISH CLASSICS THE LIFE OF SAMUEL JOHNSON BY LORD MACAULAY . * - NEW YORK •:• CINCINNATI •:• CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY Copvrigh' ',5, by American Book Company LIFE OF JOHNSOK. W. P. 2 n INTRODUCTION. Thomas Babington Macaulay, the most popular essayist of his time, was born at Leicestershire, Eng., in 1800. His father, of was a Zachary Macaulay, a friend and coworker Wilberforc^e, man "> f austere character, who was greatly shocked at his son's fondness ">r worldly literature. Macaulay's mother, however, ( encouraged his reading, and did much to foster m*? -erary tastes. " From the time that he was three," says Trevelyan in his stand- " read for the most r_ ard biography, Macaulay incessantly, part CO and a £2 lying on the rug before the fire, with his book on the ground piece of bread and butter in his hand." He early showed marks ^ of uncommon genius. When he was only seven, he took it into " —i his head to write a Compendium of Universal History." He could remember almost the exact phraseology of the books he " " rea'd, and had Scott's Marmion almost entirely by heart. His omnivorous reading and extraordinary memory bore ample fruit in the richness of allusion and brilliancy of illustration that marked " the literary style of his mature years. He could have written Sir " Charles Grandison from memory, and in 1849 he could repeat " more than half of Paradise Lost." In 1 81 8 Macaulay entered Trinity College, Cambridge. Here he in classics and but he had an invincible won prizes English ; distaste for mathematics. -

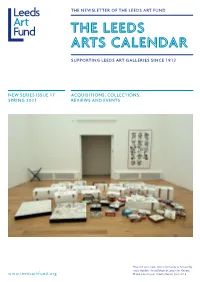

LAF out & About, in Linton in the Yorkshire Dales

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE LEEDS ART FUND SUPPORTING LEEDS ART GALLERIES SINCE 1912 NEW SERIES ISSUE 17 ACQUISITIONS, COLLECTIONS, SPRING 2021 REVIEWS AND EVENTS How the Artist was led to the Study of Nature by Andy Holden - Installation at Leeds Art Gallery. www.leedsartfund.org Photo Courtesy of Simon Warner, June 2018. RECENT ACQUISITION IMPORTANT DRAWINGS BY THOMAS CHIPPENDALE SENIOR AND JUNIOR The Chippendale Society has recently acquired six previously unknown drawings attributed to Thomas Chippendale senior and junior. The key to their attribution is provided by a drawing for a lantern pedestal, which is the design drawing for a set of six supplied by Chippendale to Harewood House in 1774. The drawings are by two different hands. Two are thought to date from about 1760 and are typical of Thomas Chippendale senior’s free-flowing style with its use of delicate washes to suggest shadow and perspective. The other four are by a different hand and can confidently be attributed to Thomas Chippendale junior (the first to be discovered) on the basis of strong similarities with his engravings published in 1779. These are the first Chippendale drawings of any kind in the fully mature neo-Classical style of the 1770s. Chippendale junior was first recorded as active in his father’s firm in 1766, aged 17, and his first signed drawing is of a neo-Classical tablet, dated 1772. However, it has long been assumed that he did not assume a significant role until c.1775-6. The new drawings demonstrate that Chippendale junior was involved much earlier than previously thought. -

Chapter 25: Uniform Titles

CHAPTER 25 UNIFORM TITLES Prepared by: Robert B. Ewald Cataloging Policy and Support Office Library of Congress 1995, revised 2001 Introduction and Acknowledgment The following pages on AACR2 Chapter 25 (uniform titles and LC’s uniform title polices and practices) are extracted from the NACO trainers’ manual. They were originally written in 1995 and revised in 2001 to reflect MARC 21 changes and minor corrections for PCC trainers presenting a NACO Training Workshop. Intended as a teacher’s vademecum, the presentation contains stylistic elements (bold face, exhortations, etc.) that may seem out of content to the casual reader. The Library of Congress Rule Interpretations for uniform titles reflect the complexity of application within a context of managing a large national card catalog. This gloss serves as the lifeline for NACO trainers, including those from LC. The Cooperative Cataloging Team is very fortunate to have available someone with the depth of experience and knowledge to elucidate this area of cataloging and we would be remiss if we did not share this document with the library community. Coop expresses its sincere thanks to Bob Ewald, CPSO, for his professional expertise and advice given to all in the spirit of cooperation. ii CHAPTER 25 UNIFORM TITLES Outline I. Use of Uniform Titles [25.1A; 253E; DCM Z1; LCRI 25.1] 1. Scope of AACR2 chapter 25 2. Library of Congress application policy on chapter 25 3. Library of Congress name authority policy on chapter 25 4. Problem areas in assigning uniform titles 5. Library of Congress maintenance policy on chapter 25 6. NACO policies on chapter 25 II. -

Proquest Dissertations

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI 61 UNIVERSITY D-OTTAWA ~ ECOLE DES GRADUES LOUISE IMOGEN GTJIHEY BIOGRAPHER by Sister Saint Kevin C.W.D. (Hawley) Thesis presented to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Ottawa in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the derree of Kaster of Arts. i Ottawa $'!> ^ Ottawa, Canada, 195& UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA ~ SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES UMI Number: EC56176 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform EC56176 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 UNIVERSITE D-OTTAWA ~ ECOLE DES GRADUES ACKNOWLEDGMENT The author wishes to thank : Professor Emmett O'Grady, Ph.D., head of the Depart ment of English, Ottawa University, under whose direction this thesis was prepared; Notre Dame College, Ottawa for the use of its library and many other services; Marianopolis College, Montreal for the extended loan of books out of print and difficult to procure; All those who rendered the author service in any way. -

George and William Strahan in Samuel Johnson's

GEORGE AND WILLIAM STRAHAN IN SAMUEL JOHNSON'S CAREER AND IMAGE By GEORGIA PRICE HENSLEY /I Bachelor of Arts East Central State College Ada, Oklahoma 1965 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 1970 / ·' GEORGE AND WILLIAM STRAHAN IN SAMUEL JOHNSON ' S ·, ,. '···, CAREER AND IMAGE '",,, " Thesis Approved : --- §~6/.Adviser ~- ~~ Dean of the Graduate College ii PREFACE In this thesis I have avoided as much as possible two almost irresistible paths that tempt many write,rs inquiring into the life and works of Samuel Johnson. The "literary gossip" surrounding and pene trating every aspect of the personalities, social lives, and works of Johnson and his circle is fascinating reading; moreover, the relation ship of Johnson to his household, the Thrales, the Burneys, and James Boswell, to name only a few may draw the attention indefinitely. Another equally tempting avenue for many is the founding of the print ing trade in eighteenth-century London, but bibliography is a special ized, lifetime study. I mention Johnson's circle and publishing concerns only as they illustrate the friendship and professional association of the Strahans and Johnson. Although I offer evidence to explain James Boswell's apparent slighting of the Strahans, this paper does not join the recent attacks upon Boswell's great biography. I shall demonstrate through a study of biographies, diaries, letters, and other papers of Johnson and his contemporaries that William Strahan and later his son, George, were of major importance in Johnson's life and works during the author's life time and extended their influence beyond his death in the publications of his works and biographies that they commissioned, I express gratitude to my professor and adviser, Dr, Loyd Douglas, for introducing me to Samuel Johnson, the author, and for encouragement and advice in continuing the research and the writing of this paper. -

Fine English Furniture & Works Of

Bonhams 101 New Bond Street London W1S 1SR +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 +44 (0) 20 7447 7400 fax 20741 Fine English Furniture & Works of Art, of Works Fine English Furniture & 6 March 2013, New Bond Street, London Bond Street, New 6 March 2013, Fine English Furniture & Works of Art Wednesday 6 March 2013 at 2pm New Bond Street, London Fine English Furniture & Works of Art Wednesday 6 March 2013 at 2pm New Bond Street, London Bonhams Enquiries Customer Services 101 New Bond Street [email protected] Monday to Friday 8.30am to 6pm London W1S 1SR +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 www.bonhams.com Furniture & Works of Art Guy Savill Please see back of catalogue Viewing +44 (0) 8700 273 604 for important notice to bidders Sunday 3 March 11am to 3pm [email protected] Monday 4 March 9am to 4.30pm Illustrations Tuesday 5 March 9am to 4.30pm Sally Stratton Front cover: Lot 20 Wednesday 6 March 9am to 12pm +44 (0) 8700 273 603 Back cover: Lot 18 [email protected] Inside front cover: Lot 285 (detail) Bids Inside back cover: Lot 285 (detail) +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 Sculpture 20741 +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax Rachael Osborn-Howard Sale Number: To bid via the internet please visit +44 (0) 8700 273 610 £20 (£25 by post) www.bonhams.com [email protected] Catalogue: Please provide details of the lots Administrator Live online bidding is on which you wish to place bids Jackie Brown available for this sale at least 24 hours prior to the sale. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STRFFT AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 . 737-4215/842-6353 Revised: July 1985 EXHIBITION FACT SHEET Title: THE TREASURE HOUSES OF BRITAIN: FIVE HUNDRED YEARS OF PRIVATE PATRONAGE AND ART COLLECTING Patrons; Their Royal Highnesses The Prince and Princess of Wales Dates: November 3, 1985 through March. 16, 1986. (This exhibition will not travel. Most loans from houses open to view are expected to remain in place until the late suitmer of 1985 and to be returned before many of the houses open for their visitors in the spring of 1986.) Credits: This exhibition is made possible by a generous grant from the Ford Motor Company. The exhibition was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, in collaboration with the British Council and is supported by indemnities from Her Majesty's Treasury and the U.S. Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities. Further British assistance was supplied by the National Trust and the Historic Houses Association. British Airways has been designated the official carrier of the exhibition. History of the exhibition; The idea that the National Gallery of Art consider holding a major exhibition devoted to British art evolved in discussions with the British Council in 1979. J. Carter Brown, Director of the National Gallery of Art, proposed an exhibition on the British country house as a "vessel of civilization," bringing together works of art illustrating the extraordinary achievement of collecting and patronage throughout Britain over the past five hundred years. As this concept carried with it the additional, contemporary advantage of stimulating greater interest in and support of those houses open to public viewing, it was enthusiastically endorsed by the late Lord Howard of Henderskelfe, then-Chairman of the Historic Houses Association, Julian Andrews, Director of the Fine Arts Department of the British Council, and Lord Gibson, Chairman of the National Trust. -

Christie's London Presents: Celebrating the Genius of Chippendale's Designs & the Perfection of His Execution 5 July 2

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 23 MAY 2018 Christie’s London Presents: Celebrating the Genius of Chippendale’s Designs & the Perfection of His Execution 5 July 2018 ‘The Shakespeare of English Furniture makers’ Christopher Gilbert London – On 5 July, Christie’s landmark sale Thomas Chippendale 300 Years will celebrate the genius of Chippendale’s designs and the perfection of his execution, in the 300th anniversary year of his birth. Taking place during Christie’s Classic Week, the dedicated London auction will present 22 lots with estimates ranging from £5,000 to £5 million. A selection of works will be on public view at Christie’s London headquarters until 25 May, with the full pre-sale exhibition opening from 30 June to 5 July. Collectively, the sale encompasses some of the grandest pieces of 18th century furniture ever created, including Sir Rowland Winn’s Commode (estimate: £3-5million) and The Dundas Sofas (each sofa with an estimate of £2-3million). Remembered as ‘The Shakespeare of English Furniture makers’, Chippendale was the master of many mediums. This is highlighted by the breadth of works being offered, including his game-changing book which made his name The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director, first published in 1754, which astutely promoted his designs to the most affluent potential clients of the day (the expanded 1762 3rd edition, estimate: £5,000-8,000) alongside works executed in giltwood, mahogany, marquetry and lacquer. Orlando Rock, Christie’s UK Chairman and Co Chairman of Decorative Arts: “This auction will present arguably the greatest neo-classical masterpieces by Thomas Chippendale that will ever come to market, providing unique opportunities to buy the very best at comparatively accessible price levels. -

THOMAS CHIPPENDALE at DUMFRIES HOUSE Work Proceeded; the Following Extract Concerns the Speci- Will Not Be Well Understood by a Small Drawing

CHRISTOPHER GILBERT Thomas Chippendaleat Dumfries House* THEpublication in I 754 of Thomas Chippendale'scelebrated the furniture he supplied during the mid-i 760's to Sir volume of designs The Gentlemanand Cabinet-Maker'sDirector Rowland Winn of Nostell Priory' and Sir Lawrence Dundas8 is generally assumed to have exercised a dramatically included pieces which reflect his early artistic ideals, they stimulating effect on his trade for it was reprinted the are seldom intimately related to plates in the Directorand following year, revised and enlarged in 1762 and all his after 1765 he rapidly assimilated the neo-classical style known commissions date from after its appearance. While formulated by Robert Adam. In fact the impressive amount there is no doubt that the volume was widely circulated and of documented Chippendale furniture dating from the time most influential surprisingly little furniture made by the when he subscribed to Adam's criteria of taste has en- author's own firm during the decade immediately following couraged the belief amongst experts that this was his 'best' its publication has been traced - there is at present evidence period - a view not shared by the present author. of only six commissions compared with twenty-six during Although the Earl of Dumfries is recorded as a patron in the remaining fifteen years of his life. Of these six the Earl the third edition of Chippendale'sDirector9 and the existence of Morton is merely named as a patron in one of the prefatory of relevant bills has been known for over fifty years'0 this notes to the third edition of the Director.'Two others, James notable collection has never been discussed in detail. -

Robert Adam's Revolution in Architecture Miranda Jane Routh Hausberg University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture Miranda Jane Routh Hausberg University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Hausberg, Miranda Jane Routh, "Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3339. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3339 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3339 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robert Adam's Revolution In Architecture Abstract ABSTRACT ROBERT ADAM’S REVOLUTION IN ARCHITECTURE Robert Adam (1728-92) was a revolutionary artist and, unusually, he possessed the insight and bravado to self-identify as one publicly. In the first fascicle of his three-volume Works in Architecture of Robert and James Adam (published in installments between 1773 and 1822), he proclaimed that he had started a “revolution” in the art of architecture. Adam’s “revolution” was expansive: it comprised the introduction of avant-garde, light, and elegant architectural decoration; mastery in the design of picturesque and scenographic interiors; and a revision of Renaissance traditions, including the relegation of architectural orders, the rejection of most Palladian forms, and the embrace of the concept of taste as a foundation of architecture. -

![Not in ESTC: --The Last Speeches and Dying Words, of John Riley, Alexander Bourk, Martin Carrol [Et Al.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8527/not-in-estc-the-last-speeches-and-dying-words-of-john-riley-alexander-bourk-martin-carrol-et-al-4238527.webp)

Not in ESTC: --The Last Speeches and Dying Words, of John Riley, Alexander Bourk, Martin Carrol [Et Al.]

The 2017 EC/ASECS Presidential Address By Eugene Hammond First of all, profound thanks to Emily Kugler for coordinating this year’s EC/ASECS conference. Managing a conference requires the full gamut of skills, from managing a diminutive budget constantly in flux, to negotiating as a novice with hotels who negotiate for a living, to persuading one’s university to make a few concessions in their usual access policies, to keeping faculty busy elsewhere with their teaching on time with their conference tasks, to mastering technology and emergency technology repair, to guessing when and how important coffee is to participants, to keeping cool under pressure, to giving up much of your leisure for a year. I’ve only scratched the surface. I have coordinated only two conferences in my career, and they were the most taxing professional experiences I’ve had. Doing this work is satisfying at the end when you see your conference take intellectual shape, but until that climax many, many times you doubt your common sense for having agreed to do this job. Second, it is moving to be back here at Howard where we held a funeral service for Maurice Bennett, my officemate at the University of Maryland in the early 80s, and who died of AIDS in the early 90s. Third, I’d like to express my deep gratitude to this organization, EC/ASECS, that saved me during the 14 years that I left university teaching to teach high school; EC/ASECS has consistently been a collection of people and of scholars, not of ranks.