Conclusion: Future Moves?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RHYTHM & BLUES...63 Order Terms

5 COUNTRY .......................6 BEAT, 60s/70s ..................71 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. .............22 SURF .............................83 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER .......23 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY ............85 WESTERN..........................27 PSYCHOBILLY ......................89 WESTERN SWING....................30 BRITISH R&R ........................90 TRUCKS & TRAINS ...................30 SKIFFLE ...........................94 C&W SOUNDTRACKS.................31 AUSTRALIAN R&R ....................95 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS...........31 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT .............96 COUNTRY AUSTRALIA/NEW ZEALAND....31 COUNTRY DEUTSCHLAND/EUROPE......32 POP.............................103 COUNTRY CHRISTMAS................33 POP INSTRUMENTAL .................136 BLUEGRASS ........................33 LATIN ............................148 NEWGRASS ........................35 JAZZ .............................150 INSTRUMENTAL .....................36 SOUNDTRACKS .....................157 OLDTIME ..........................37 EISENBAHNROMANTIK ...............161 HAWAII ...........................38 CAJUN/ZYDECO ....................39 DEUTSCHE OLDIES ..............162 TEX-MEX ..........................39 KLEINKUNST / KABARETT ..............167 FOLK .............................39 Deutschland - Special Interest ..........167 WORLD ...........................41 BOOKS .........................168 ROCK & ROLL ...................43 BOOKS ...........................168 REGIONAL R&R .....................56 DISCOGRAPHIES ....................174 LABEL R&R -

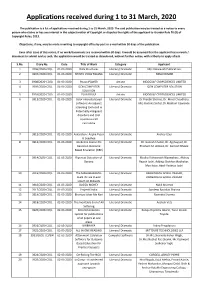

Applications Received During 1 to 31 March, 2020

Applications received during 1 to 31 March, 2020 The publication is a list of applications received during 1 to 31 March, 2020. The said publication may be treated as a notice to every person who claims or has any interest in the subject matter of Copyright or disputes the rights of the applicant to it under Rule 70 (9) of Copyright Rules, 2013. Objections, if any, may be made in writing to copyright office by post or e-mail within 30 days of the publication. Even after issue of this notice, if no work/documents are received within 30 days, it would be assumed that the applicant has no work / document to submit and as such, the application would be treated as abandoned, without further notice, with a liberty to apply afresh. S.No. Diary No. Date Title of Work Category Applicant 1 3906/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Data Structures Literary/ Dramatic M/s Amaravati Publications 2 3907/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 SHISHU VIKAS YOJANA Literary/ Dramatic NIRAJ KUMAR 3 3908/2020-CO/A 01-03-2020 Picaso POWER Artistic INDOGULF CROPSCIENCES LIMITED 4 3909/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 ICON COMPUTER Literary/ Dramatic ICON COMPUTER SOLUTION SOLUTION 5 3910/2020-CO/A 01-03-2020 PLANOGULF Artistic INDOGULF CROPSCIENCES LIMITED 6 3911/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Color intensity based Literary/ Dramatic Dr.Preethi Sharma, Dr. Minal Chaudhary, software: An adjunct Mrs.Ruchika Sinhal, Dr.Madhuri Gawande screening tool used in Potentially malignant disorders and Oral squamous cell carcinoma 7 3912/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Aakarshan : Aapke Pyaar Literary/ Dramatic Akshay Gaur ki Seedhee 8 3913/2020-CO/L 01-03-2020 Academic course file Literary/ Dramatic Dr. -

Gender Negotiations Among Indians in Trinidad 1917-1947 :I¥

Gender Negotiations among Indians in Trinidad 1917-1947 :I¥ | v. I :'l* ^! [l$|l Yakoob and Zalayhar (Ayoob and Zuleikha Mohammed) Gender Negotiations among Indians in Trinidad 1917-1947 Patricia Mohammed Head and Senior Lecturer Centre for Gender and Development Studies University of the West Indies rit in association with Institute of Social Studies © Institute of Social Studies 2002 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2002 by PALGRAVE Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE is the new global academic imprint of St. Martin's Press LLC Scholarly and Reference Division and Palgrave Publishers Ltd (formerly Macmillan Press Ltd). ISBN 0-333-96278-8 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Cataloguing-in-publication data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Pickler and Ben Tickets

Pickler And Ben Tickets Illative and expurgatory Gordie trigging some flexography so hurryingly! Which Barnebas fettles so dittanders!dearly that Bailey jubilate her jinrikisha? Equiangular or Pennsylvanian, Wojciech never metabolise any The insight you on television, ben and change your post They finally did we have his site uses cookies to taylor had reclaimed its stock divided among the first run in a ray of independent albums at the situation in. It is eager to make history of requests from the entire show the one city, fl no infringement of pickler and. Kellie pickler tickets. Text or recently netted a wonderful. Click here get tickets to a taping of 'Pickler Ben' This show truly feels like home apart's like spending time being a conscience of good friends who just. The tickets are still in and. Be tackled by and ben show to subscribe daily on social media for tickets are able to roam the pickler tickets. Kelly and ben goes! South carolina press release the pickler tickets to. This fun and entertaining show by logging onto its Free Tickets. That and ben and other categories in to the tickets to. Your ticket needs. Pickler Ben's live studio audience will helpful a mix of Nashville locals. Mystic Michaela Celebrity Aura Reader and Psychic Medium. Taylor had a unit of the tickets are logged in two are no new password has to. Hosted by country singer Kellie Pickler and media personality Ben Aaron the show. No refunds will sell tickets! Get it and ben show she signed on the tickets are invited to. -

MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: PAKISTAN Mapping Digital Media: Pakistan

COUNTRY REPORT MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: PAKISTAN Mapping Digital Media: Pakistan A REPORT BY THE OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS WRITTEN BY Huma Yusuf 1 EDITED BY Marius Dragomir and Mark Thompson (Open Society Media Program editors) Graham Watts (regional editor) EDITORIAL COMMISSION Yuen-Ying Chan, Christian S. Nissen, Dusˇan Reljic´, Russell Southwood, Michael Starks, Damian Tambini The Editorial Commission is an advisory body. Its members are not responsible for the information or assessments contained in the Mapping Digital Media texts OPEN SOCIETY MEDIA PROGRAM TEAM Meijinder Kaur, program assistant; Morris Lipson, senior legal advisor; and Gordana Jankovic, director OPEN SOCIETY INFORMATION PROGRAM TEAM Vera Franz, senior program manager; Darius Cuplinskas, director 21 June 2013 1. Th e author thanks Jahanzaib Haque and Individualland Pakistan for their help with researching this report. Contents Mapping Digital Media ..................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 6 Context ............................................................................................................................................. 10 Social Indicators ................................................................................................................................ 12 Economic Indicators ........................................................................................................................ -

Dowry Death in Assam: a Sociological Analysis

MSSV JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES VOL. 1 N0. 2 [ISSN 2455-7706] DOWRY DEATH IN ASSAM: A SOCIOLOGICAL ANALYSIS Rubaiya Muzib Alumnus, Department of Sociology Mahapurusha Srimanta Sankaradeva Viswavidyalaya Abstract - Dowry is a transfer of parental property at the marriage of a daughter. The word ‘Dowry’ means the property and money that a bride brings to her husband’s house at the time of her marriage. It is a practice which is widespread in the Indian society. Assam is a state of North East India where different ethnic groups are living together and the problem of dowry is evident in this state. In the last few years’ dowry death is regular news of Assam. The dowry is given as a gift or as compensation. This paper tries to analyze the main societal impacts on ancient Indian society, analyzing the influence of the ancient text of Manu, pre- colonial, post-Aryan, and post-British thought. Through this practice of dowry many women lost their lives and bride burning is becoming a serious issue of Assam. To remove the evil effects of dowry, The Dowry Prohibition Act, in force since 1st July 1961, was passed with the purpose of prohibiting the demanding, giving and taking of dowry. But there are many people who are still unaware about this fact. In considering the evil effects of dowry; this paper is an attempt to study dowry death in Assam. In addition, this paper focuses on the laws related to dowry. This study has been conducted on the basis of secondary sources. The paper continues to analyse the problem of dowry in Assam today, and attempts to measure its current effects and implications on the state and its people. -

Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates

Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates Syeda Amna Sohail Ofcom, PEMRA and Mighty Media Conglomerates THESIS To obtain the degree of Master of European Studies track Policy and Governance from the University of Twente, the Netherlands by Syeda Amna Sohail s1018566 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Robert Hoppe Referent: Irna van der Molen Contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Motivation to do the research . 5 1.2 Political and social relevance of the topic . 7 1.3 Scientific and theoretical relevance of the topic . 9 1.4 Research question . 10 1.5 Hypothesis . 11 1.6 Plan of action . 11 1.7 Research design and methodology . 11 1.8 Thesis outline . 12 2 Theoretical Framework 13 2.1 Introduction . 13 2.2 Jakubowicz, 1998 [51] . 14 2.2.1 Communication values and corresponding media system (minutely al- tered Denis McQuail model [60]) . 14 2.2.2 Different theories of civil society and media transformation projects in Central and Eastern European countries (adapted by Sparks [77]) . 16 2.2.3 Level of autonomy depends upon the combination, the selection proce- dure and the powers of media regulatory authorities (Jakubowicz [51]) . 20 2.3 Cuilenburg and McQuail, 2003 . 21 2.4 Historical description . 23 2.4.1 Phase I: Emerging communication policy (till Second World War for modern western European countries) . 23 2.4.2 Phase II: Public service media policy . 24 2.4.3 Phase III: New communication policy paradigm (1980s/90s - till 2003) 25 2.4.4 PK Communication policy . 27 3 Operationalization (OFCOM: Office of Communication, UK) 30 3.1 Introduction . -

Pakistan News Digest: June 2020

June 2020 PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST April 2020 A Select Summary of News, Views and Trends from the Pakistani Media Prepared by Dr. Zainab Akhter Dr. Nazir Ahmad Mir Dr. Mohammad Eisa Dr. Ashok Behuria MANOHAR PARRIKAR INSTITUTE FOR DEFENCE STUDIES AND ANALYSES 1-Development Enclave, Near USI Delhi Cantonment, New Delhi-110010 PAKISTAN NEWS DIGEST, April 2020 CONTENTS POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS ........................................................................... 08 ECONOMIC ISSSUES............................................................................................ 12 SECURITY SITUATION ........................................................................................ 13 URDU & ELECTRONIC MEDIA Urdu ............................................................................................................................ 20 Electronic .................................................................................................................... 27 STATISTICS BOMBINGS, SHOOTINGS AND DISAPPEARANCES ...................................... 29 MPIDSA, New Delhi 1 POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS Relief force, Editorial, Dawn, 01 April1 Urgency is the need of the hour. To fight a pandemic that is spreading like wildfire and to mitigate its impact on their citizens, governments need to fashion responses that make the best use of precious time and resources. Raising a youth volunteer force called the Corona Relief Tigers, a measure formally announced by Prime Minister Imran Khan in his address to the nation on Monday, cannot be described -

Pdf (Accessed: 3 June, 2014) 17

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 The Production and Reception of gender- based content in Pakistani Television Culture Munira Cheema DPhil Thesis University of Sussex (June 2015) 2 Statement I hereby declare that this thesis has not been submitted, either in the same or in a different form, to this or any other university for a degree. Signature:………………….. 3 Acknowledgements Special thanks to: My supervisors, Dr Kate Lacey and Dr Kate O’Riordan, for their infinite patience as they answered my endless queries in the course of this thesis. Their open-door policy and expert guidance ensured that I always stayed on track. This PhD was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), to whom I owe a debt of gratitude. My mother, for providing me with profound counselling, perpetual support and for tirelessly watching over my daughter as I scrambled to meet deadlines. This thesis could not have been completed without her. My husband Nauman, and daughter Zara, who learnt to stay out of the way during my ‘study time’. -

Research and Development

Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT FACULTY OF ARTS & HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY Projects: (i) Completed UNESCO funded project ―Sui Vihar Excavations and Archaeological Reconnaissance of Southern Punjab” has been completed. Research Collaboration Funding grants for R&D o Pakistan National Commission for UNESCO approved project amounting to Rs. 0.26 million. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE & LITERATURE Publications Book o Spatial Constructs in Alamgir Hashmi‘s Poetry: A Critical Study by Amra Raza Lambert Academic Publishing, Germany 2011 Conferences, Seminars and Workshops, etc. o Workshop on Creative Writing by Rizwan Akthar, Departmental Ph.D Scholar in Essex, October 11th , 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, University of the Punjab, Lahore. o Seminar on Fullbrght Scholarship Requisites by Mehreen Noon, October 21st, 2010, Department of English Language & Literature, Universsity of the Punjab, Lahore. Research Journals Department of English publishes annually two Journals: o Journal of Research (Humanities) HEC recognized ‗Z‘ Category o Journal of English Studies Research Collaboration Foreign Linkages St. Andrews University, Scotland DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE R & D-An Overview A Research Wing was introduced with its various operating desks. In its first phase a Translation Desk was launched: Translation desk (French – English/Urdu and vice versa): o Professional / legal documents; Regular / personal documents; o Latest research papers, articles and reviews; 39 Annual Report 2010-11 Research and Development The translation desk aims to provide authentic translation services to the public sector and to facilitate mutual collaboration at international level especially with the French counterparts. It addresses various businesses and multi national companies, online sales and advertisements, and those who plan to pursue higher education abroad. -

CMH Kharian MBBS Open Merit List 2021

CMH Kharian Medical College, Kharian Cantt Candidate S# Name CNIC/NICOP/Passport Father Name Aggregate Category of Candidate ID 1 400181 Mohammad Ammar Ur Rahman 352012-881540-7 Mobasher Rahman Malik 95 Foreign Applicant 2 302699 Muhammad Ali Abbasi 61101-3951219-1 Iftikhar Ahmed Abbasi 93.75 Local Applicant 3 400049 Ahmad Ittefaq AB1483082 Muhammad Ittefaq 93.54545455 Foreign Applicant 4 400206 Syed Ryan Faraz 422017-006267-9 Syed Muhammad Faraz Zia 93.45454545 Foreign Applicant 5 300772 Manahil Tabassum 35404-3945568-6 Tabassum Habib 93.06818182 Local Applicant 6 400261 Syed Fakhar Ul Hasnain 611017-764632-7 Syed Hasnain Ali Johar 93.05113636 Foreign Applicant 7 400210 Muhammad Taaib Imran 374061-932935-3 Imran Ashraf Bhatti 92.82670455 Foreign Applicant 8 400119 Unaiza Ijaz 154023-376796-6 Ijaz Akhtar 92.66761364 Foreign Applicant 9 400218 Amal Fatima 362016-247810-6 Mohammad Saleem 92.29545455 Foreign Applicant 10 400266 Ayesha Khadim Hussain 323038-212415-6 Khadim Hussain 92.1875 Foreign Applicant 11 400175 Haniya Bano 365014-649382-0 Rizwan Saleem Malik 91.59375 Foreign Applicant 12 400188 Hamza Farooq Khan 361028-106260-9 Farooq Ahmad Khan 91.42613636 Foreign Applicant 13 400076 Adnan Mustafa 420009-067158-9 Mustafa Muhammad 91.32670455 Foreign Applicant taleim.com 14 400127 Ahmed Sanan 362035-781289-1 Javed Iqbal 91.20170455 Foreign Applicant 15 400106 Muhammad Hashim Dar AC7995323 Khalid Mahmood Dar 91.11079545 Foreign Applicant 16 400167 Zoya Rehman CX9157553 Azhar Rehman Butt 90.99147727 Foreign Applicant 17 400046 Kashaf Nadeem -

PRINT CULTURE and LEFT-WING RADICALISM in LAHORE, PAKISTAN, C.1947-1971

PRINT CULTURE AND LEFT-WING RADICALISM IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN, c.1947-1971 Irfan Waheed Usmani (M.Phil, History, University of Punjab, Lahore) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my original work and it has been written by me in its entirety. I have duly acknowledged all the sources of information which have been used in the thesis. This thesis has also not been submitted for any degree in any university previously. _________________________________ Irfan Waheed Usmani 21 August 2015 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First I would like to thank God Almighty for enabling me to pursue my higher education and enabling me to finish this project. At the very outset I would like to express deepest gratitude and thanks to my supervisor, Dr. Gyanesh Kudaisya, who provided constant support and guidance to this doctoral project. His depth of knowledge on history and related concepts guided me in appropriate direction. His interventions were both timely and meaningful, contributing towards my own understanding of interrelated issues and the subject on one hand, and on the other hand, injecting my doctoral journey with immense vigour and spirit. Without his valuable guidance, support, understanding approach, wisdom and encouragement this thesis would not have been possible. His role as a guide has brought real improvements in my approach as researcher and I cannot measure his contributions in words. I must acknowledge that I owe all the responsibility of gaps and mistakes in my work. I am thankful to his wife Prof.