Coral Reef Fishes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Megan E

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School November 2017 Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Megan E. Hepner University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Other Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Hepner, Megan E., "Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7408 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary by Megan E. Hepner A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Marine Science with a concentration in Marine Resource Assessment College of Marine Science University of South Florida Major Professor: Frank Muller-Karger, Ph.D. Christopher Stallings, Ph.D. Steve Gittings, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 31st, 2017 Keywords: Species richness, biodiversity, functional diversity, species traits Copyright © 2017, Megan E. Hepner ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to my major advisor, Dr. Frank Muller-Karger, who provided opportunities for me to strengthen my skills as a researcher on research cruises, dive surveys, and in the laboratory, and as a communicator through oral and presentations at conferences, and for encouraging my participation as a full team member in various meetings of the Marine Biodiversity Observation Network (MBON) and other science meetings. -

Identification Guide to the Common Coatal Food Fishes of the Pacific Region-48-53

YDX Myripristis adusta Holocentridae / Soldierfish and Squirrelfish Shadowfin soldierfish Silvery-salmon pink with 1 dark 3 1 scale margins, particularly on upper body. 2 Reddish-black spot on rear margin of gill covers and 3 reddish-black margins on soft dorsal, anal and caudal fins. Max length: 30 cm FL AS CK FJ FM GU KI 2 MH MP NC NR NU PF PG PN PW SB TK TO TV VU WF WS YDX Myripristis amaena Holocentridae / Soldierfish and Squirrelfish Brick soldierfish Silvery-red with 1 dark scale 1 margins and 2 dark red band on margin of gill covers. 3 Dorsal, anal and caudal fins red without white margins. Max length: 27 cm FL AS CK FJ FM GU KI MH MP NC NR NU PF 2 3 PG PN PW SB TK TO TV VU WF WS Similar to Myripristis violacea but without white margins on soft dorsal, anal and caudal fins. YJW Myripristis berndti Holocentridae / Soldierfish and Squirrelfish Blotcheye soldierfish, bigscale soldierfish 4 White with red tints and 1 red 1 scale margins. 2 Dark margin on gill covers and 3 white margins on soft dorsal, pelvic, anal and caudal fins.4 Outer part of spiny dorsal fin orange-yellow. Max length: 28 cm FL AS CK FJ FM GU KI 2 MH MP NC NR NU PF PG PN PW SB TK TO 3 TV VU WF WS Similar to Myripristis kuntee but with much larger scales and a redder overall appearance. 48 Holocentridae / Soldierfish and Squirrelfish Myripristis kuntee YJZ Shoulderbar soldierfish 2 Silvery orange-red with 1 darker scale margins. -

Coral Reef Fishes Which Forage in the Water Column

HelgotS.nder wiss. Meeresunters, 24, 292-306 (1973) Coral reef fishes which forage in the water column A review of their morphology, behavior, ecology and evolutionary implications W. P. DAVIS1, & R. S. BIRDSONG2 1 Mediterranean Marine Sorting Center; Khereddine, Tunisia, and 2 Department of Biology, Old Dominion University; Norfolk, Virginia, USA EXTRAIT: <<Fourrages. des poissons des r&ifs de coraux dans la colonne d'eau: Morpholo- gie, comportement, &ologie et ~volution. Dans un biotope ~t r&if de coraiI, des esp&es &roitement li~es peuvent servir d'exempIe de diff~renciatlon sur le plan de t'~volutlon. La radiation ~volutive de poissons repr&entant plusieurs familles du r~eif corallien tropical a conduit ~t plusieurs reprises ~t la formation de <dourragers dans la colonne d'eam>. Ce mode de vie comporte une s~rie de caract~res morphologiques et &hologiques d~finis. On trouve des ~xemples similaires dans I'eau douce et dans des habitats non tropicaux. Les traits distinctifs de cette sp&ialisation, la syst6matique, les caract~rlstiques &ologiques et celies se rapportant ~t l'6volution sont d&rits et discut~s. INTRODUCTION The rapid adoption of in situ studies to investigate lifeways of organisms in the oceans is succeeding in bringing the laboratory to the ocean. Before, the conclusions that observers and scientists were classically forced to accept oPcen represented in- accurate abstractions of things that could not be observed. During the past 10-20 years the cataloging of the fauna and flora of the coral reef habitats has been carried out at an escalated rate, coupled with the many and vast improvements in tools, allowing increased periods of continual observation under sea. -

Spatial and Temporal Distribution of the Demersal Fish Fauna in a Baltic Archipelago As Estimated by SCUBA Census

MARINE ECOLOGY - PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 23: 3143, 1985 Published April 25 Mar. Ecol. hog. Ser. 1 l Spatial and temporal distribution of the demersal fish fauna in a Baltic archipelago as estimated by SCUBA census B.-0. Jansson, G. Aneer & S. Nellbring Asko Laboratory, Institute of Marine Ecology, University of Stockholm, S-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden ABSTRACT: A quantitative investigation of the demersal fish fauna of a 160 km2 archipelago area in the northern Baltic proper was carried out by SCUBA census technique. Thirty-four stations covering seaweed areas, shallow soft bottoms with seagrass and pond weeds, and deeper, naked soft bottoms down to a depth of 21 m were visited at all seasons. The results are compared with those obtained by traditional gill-net fishing. The dominating species are the gobiids (particularly Pornatoschistus rninutus) which make up 75 % of the total fish fauna but only 8.4 % of the total biomass. Zoarces viviparus, Cottus gobio and Platichtys flesus are common elements, with P. flesus constituting more than half of the biomass. Low abundance of all species except Z. viviparus is found in March-April, gobies having a maximum in September-October and P. flesus in November. Spatially, P. rninutus shows the widest vertical range being about equally distributed between surface and 20 m depth. C. gobio aggregates in the upper 10 m. The Mytilus bottoms and the deeper soft bottoms are the most populated areas. The former is characterized by Gobius niger, Z. viviparus and Pholis gunnellus which use the shelter offered by the numerous boulders and stones. The latter is totally dominated by P. -

State of the Coral Triangle: Solomon Islands

State of the Coral Triangle: Solomon Islands One of a series of six reports on the status of marine resources in the western Pacific Ocean, the State of the Coral Triangle: Solomon Islands describes the biophysical characteristics of Solomon Islands’ coastal and marine ecosystems, the manner in which they are being exploited, the framework in place that governs their use, the socioeconomic characteristics of the communities that use them, and the environmental threats posed by the manner in which STATE OF THE CORAL TRIANGLE: they are being used. It explains the country’s national plan of action to address these threats and improve marine resource management. Solomon Islands About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to approximately two-thirds of the world’s poor: 1.6 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, with 733 million struggling on less than $1.25 a day. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org Printed on recycled paper Printed in the Philippines STATE OF THE CORAL TRIANGLE: Solomon Islands © 2014 Asian Development Bank All rights reserved. -

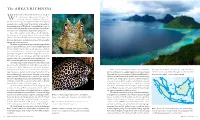

The AREA's RICHNESS

The AREA’S RICHNESS hile there is little doubt that the Coral Triangle is the richest marine environment on the planet, the reasons for the richness are hotly debated. Is it because Wthe richest taxonomic groups originated in the Coral Triangle and dispersed to the rest of the world? Or is it because of the overlap of flora and fauna from the West Pacific Ocean and Indian Ocean? As it turns out, the only thing that is clear is that the reasons for the area’s richness are complex and no single model explains it all. Some of the many factors that influence the diversity of the Coral Triangle are the geological history of the region, including plate tectonics and sea-level fluctuations; how species disperse and the factors that facilitate or inhibit dispersal; general biogeographic patterns and evolutionary forces. The tropics are generally more species rich than temperate and polar areas particularly because of the constant sunlight regime and weather stability. Without a winter period, organisms can flourish year round and put more energy into specialization than into preparing for long periods with reduced sunlight. This is as true in the marine realm as it is in the forests, where light and relatively constant warm water temperatures persist throughout the year. However, coastal tropical waters are relatively nutrient poor. The annual changes in water temperatures of the temperate and polar seas produce mixing when the surface waters cool and sink to the bottom. The displaced bottom waters, rich with dead plankton that has sank to the depths, are forced to the surface and result in Due to ocean circulation patterns and the rotation of the Earth, As the glaciers melted and sea levels rose, the newly evolved species huge explosions of zooplankton and fish populations. -

Fish Larvae, Development, Allometric Growth, and the Aquatic Environment

II. Developmental and environmental interactions ICES mar. Sei. Symp., 201: 21-34. 1995 Fish larvae, development, allometric growth, and the aquatic environment J. W. M. Osse and J. G. M. van den Boogaart Osse, J. W. M., and van den Boogaart, J. G. M. 1995. Fish larvae, development, allometric growth, and the aquatic environment. - ICES mar. Sei. Symp., 201: 21-34. During metamorphosis, fish larvae undergo rapid changes in external appearance and dimensions of body parts. The juveniles closely resemble the adult form. The focus of the present paper is the comparison of stages of development of fishes belonging within different taxa in a search for general patterns. The hypothesis that these patterns reflect the priorities of vital functions, e.g., feeding, locomotion, and respiration, is tested taking into account the size-dependent influences of the aquatic environment on the larvae. A review of some literature on ailometries of fish larvae is given and related to the rapidly changing balance between inertial and viscous forces in relation to body length and swimming velocity. New data on the swimming of larval and juvenile carp are presented. It is concluded that the patterns of development and growth shows in many cases a close parallel with the successive functional requirements. J. W. M. Osse and J. G. M. van den Boogaart: Wageningen Agricultural University, Department of Experimental Animal Morphology and Cell Biology, Marijkeweg 40, 6709 PG Wageningen, The Netherlands [tel: (+31) (0)317 483509, fax: (+31) (0)317 483962], Introduction Fish larvae, being so small, must have problems using their limited resources for maintenance, activity, obtain Fish larvae are the smallest free-living vertebrates. -

US Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan—Pacific Region

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan Conservation Seabird Pacific Region U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Seabird Conservation Plan—Pacific Region 120 0’0"E 140 0’0"E 160 0’0"E 180 0’0" 160 0’0"W 140 0’0"W 120 0’0"W 100 0’0"W RUSSIA CANADA 0’0"N 0’0"N 50 50 WA CHINA US Fish and Wildlife Service Pacific Region OR ID AN NV JAP CA H A 0’0"N I W 0’0"N 30 S A 30 N L I ort I Main Hawaiian Islands Commonwealth of the hwe A stern A (see inset below) Northern Mariana Islands Haw N aiian Isla D N nds S P a c i f i c Wake Atoll S ND ANA O c e a n LA RI IS Johnston Atoll MA Guam L I 0’0"N 0’0"N N 10 10 Kingman Reef E Palmyra Atoll I S 160 0’0"W 158 0’0"W 156 0’0"W L Howland Island Equator A M a i n H a w a i i a n I s l a n d s Baker Island Jarvis N P H O E N I X D IN D Island Kauai S 0’0"N ONE 0’0"N I S L A N D S 22 SI 22 A PAPUA NEW Niihau Oahu GUINEA Molokai Maui 0’0"S Lanai 0’0"S 10 AMERICAN P a c i f i c 10 Kahoolawe SAMOA O c e a n Hawaii 0’0"N 0’0"N 20 FIJI 20 AUSTRALIA 0 200 Miles 0 2,000 ES - OTS/FR Miles September 2003 160 0’0"W 158 0’0"W 156 0’0"W (800) 244-WILD http://www.fws.gov Information U.S. -

Phylogeny of the Damselfishes (Pomacentridae) and Patterns of Asymmetrical Diversification in Body Size and Feeding Ecology

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.07.430149; this version posted February 8, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Phylogeny of the damselfishes (Pomacentridae) and patterns of asymmetrical diversification in body size and feeding ecology Charlene L. McCord a, W. James Cooper b, Chloe M. Nash c, d & Mark W. Westneat c, d a California State University Dominguez Hills, College of Natural and Behavioral Sciences, 1000 E. Victoria Street, Carson, CA 90747 b Western Washington University, Department of Biology and Program in Marine and Coastal Science, 516 High Street, Bellingham, WA 98225 c University of Chicago, Department of Organismal Biology and Anatomy, and Committee on Evolutionary Biology, 1027 E. 57th St, Chicago IL, 60637, USA d Field Museum of Natural History, Division of Fishes, 1400 S. Lake Shore Dr., Chicago, IL 60605 Corresponding author: Mark W. Westneat [email protected] Journal: PLoS One Keywords: Pomacentridae, phylogenetics, body size, diversification, evolution, ecotype Abstract The damselfishes (family Pomacentridae) inhabit near-shore communities in tropical and temperature oceans as one of the major lineages with ecological and economic importance for coral reef fish assemblages. Our understanding of their evolutionary ecology, morphology and function has often been advanced by increasingly detailed and accurate molecular phylogenies. Here we present the next stage of multi-locus, molecular phylogenetics for the group based on analysis of 12 nuclear and mitochondrial gene sequences from 330 of the 422 damselfish species. -

An Overview of the Dwarfgobies, the Second Most Speciose Coral-Reef Fish Genus (Teleostei: Gobiidae:Eviota )

An overview of the dwarfgobies, the second most speciose coral-reef fish genus (Teleostei: Gobiidae:Eviota ) DAVID W. GREENFIELD Research Associate, Department of Ichthyology, California Academy of Sciences, 55 Music Concourse Dr., Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, California 94118-4503, USA Professor Emeritus, University of Hawai‘i Mailing address: 944 Egan Ave., Pacific Grove, CA 93950, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract An overview of the dwarfgobies in the genus Eviota is presented. Background information is provided on the taxonomic history, systematics, reproduction, ecology, geographic distribution, genetic studies, and speciation of dwarfgobies. Future research directions are discussed. A list of all valid species to date is included, as well as tables with species included in various cephalic sensory-canal pore groupings. Key words: review, taxonomy, systematics, ichthyology, ecology, behavior, reproduction, evolution, coloration, Indo-Pacific Ocean, gobies. Citation: Greenfield, D.W. (2017) An overview of the dwarfgobies, the second most speciose coral-reef fish genus (Teleostei: Gobiidae: Eviota). Journal of the Ocean Science Foundation, 29, 32–54. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1115683 Introduction The gobiid genus Eviota, known as dwarfgobies, is a very speciose genus of teleost fishes, with 113 valid described species occurring throughout the Indo-Pacific Ocean (Table 1), and many more awaiting description. It is the fifth most speciose saltwater teleost genus, and second only to the 129 species in the eel genusGymnothorax in the coral-reef ecosystem (Eschmeyer et al. 2017). Information on the systematics and biology of the species of the genus is scattered in the literature, often in obscure references, and, other than the taxonomic key to all the species in the genus (Greenfield & Winterbottom 2016), no recent overview of the genus exists. -

Comparison of an Active and a Passive Age-0 Fish Sampling Gear in a Tropical Reservoir

Comparison of an Active and a Passive Age-0 Fish Sampling Gear in a Tropical Reservoir M. Clint Lloyd, Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Aquaculture, Mississippi State University, Box 9690 Mississippi State, MS 39762 J. Wesley Neal, Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Aquaculture, Mississippi State University, Box 9690 Mississippi State, MS 39762 Abstract: Age-0 fish sampling is an important tool for predicting recruitment success and year-class strength of cohorts in fish populations. In Puerto Rico, limited research has been conducted on age-0 fish sampling with no studies addressing reservoir systems. In this study, we compared the efficacy of passively-fished light traps and actively-fished push nets for sampling the limnetic age-0 fish community in a tropical reservoir. Diversity of catch between push nets and light traps were similar, although species composition of catches differed between gears (pseudo-F = 32.21, df =1,23, P < 0.001) and among seasons (pseudo-F = 4.29, df = 3,23, P < 0.006). Push-net catches were dominated by threadfin shad (Dorosoma petenense), comprising 94.2% of total catch. Conversely, light traps collected primarily channel catfish Ictalurus( punctatus; 76.8%), with threadfin shad comprising only 13.8% of the sample. Light-trap catches had less species diversity and evenness compared to push nets, consequently their efficiency may be limited to presence/ absence of species. These two gears sampled different components of the age-0 fish community and therefore, gear selection should be based on- re search goals, with push nets an ideal gear for threadfin shad age-0 fish sampling, and light traps more appropriate for community sampling. -

Solomon Islands Marine Life Information on Biology and Management of Marine Resources

Solomon Islands Marine Life Information on biology and management of marine resources Simon Albert Ian Tibbetts, James Udy Solomon Islands Marine Life Introduction . 1 Marine life . .3 . Marine plants ................................................................................... 4 Thank you to the many people that have contributed to this book and motivated its production. It Seagrass . 5 is a collaborative effort drawing on the experience and knowledge of many individuals. This book Marine algae . .7 was completed as part of a project funded by the John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation Mangroves . 10 in Marovo Lagoon from 2004 to 2013 with additional support through an AusAID funded community based adaptation project led by The Nature Conservancy. Marine invertebrates ....................................................................... 13 Corals . 18 Photographs: Simon Albert, Fred Olivier, Chris Roelfsema, Anthony Plummer (www.anthonyplummer. Bêche-de-mer . 21 com), Grant Kelly, Norm Duke, Corey Howell, Morgan Jimuru, Kate Moore, Joelle Albert, John Read, Katherine Moseby, Lisa Choquette, Simon Foale, Uepi Island Resort and Nate Henry. Crown of thorns starfish . 24 Cover art: Steven Daefoni (artist), funded by GEF/IWP Fish ............................................................................................ 26 Cover photos: Anthony Plummer (www.anthonyplummer.com) and Fred Olivier (far right). Turtles ........................................................................................... 30 Text: Simon Albert,