Extreme Fire Behavior: Understanding the Hazards Ed Hartin, MS, EFO, Mifiree, CFO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Art of Reading Smoke for Rapid Decision Making

The Art of Reading Smoke for Rapid Decision Making Dave Dodson teaches the art of reading smoke. This is an important skill since fighting fires in the year 2006 and beyond will be unlike the fires we fought in the 1900’s. Composites, lightweight construction, engineered structures, and unusual fuels will cause hostile fires to burn hotter, faster, and less predictable. Concept #1: “Smoke” is FUEL! Firefighters use the term “smoke” when addressing the solids, aerosols, and gases being produced by the hostile fire. Soot, dust, and fibers make up the solids. Aerosols are suspended liquids such as water, trace acids, and hydrocarbons (oil). Gases are numerous in smoke – mass quantities of Carbon Monoxide lead the list. Concept #2: The Fuels have changed: The contents and structural elements being burned are of LOWER MASS than previous decades. These materials are also more synthetic than ever. Concept #3: The Fuels have triggers There are “Triggers” for Hostile Fire Events. Flash point triggers a smoke explosion. Fire Point triggers rapid fire spread, ignition temperature triggers auto ignition, Backdraft, and Flashover. Hostile fire events (know the warning signs): Flashover: The classic American Version of a Flashover is the simultaneous ignition of fuels within a compartment due to reflective radiant heat – the “box” is heat saturated and can’t absorb any more. The British use the term Flashover to describe any ignition of the smoke cloud within a structure. Signs: Turbulent smoke, rollover, and auto-ignition outside the box. Backdraft: A “true” backdraft occurs when oxygen is introduced into an O2 deficient environment that is charged with gases (pressurized) at or above their ignition temperature. -

Fire Extinguisher Booklet

NY Fire Consultants, Inc. NY Fire Safety Institute 481 Eighth Avenue, Suite 618 New York, NY 10001 (212) 239 9051 (212) 239 9052 fax Fire Extinguisher Training The Fire Triangle In order to understand how fire extinguishers work, you need to understand some characteristics of fire. Four things must be present at the same time in order to produce fire: 1. Enough oxygen to sustain combustion, 2. Enough heat to raise the material to its ignition temperature, 3. Some sort of fuel or combustible material, and 4. The chemical, exothermic reaction that is fire. Oxygen, heat, and fuel are frequently referred to as the "fire triangle." Add in the fourth element, the chemical reaction, and you actually have a fire "tetrahedron." The important thing to remember is: take any of these four things away, and you will not have a fire or the fire will be extinguished. Essentially, fire extinguishers put out fire by taking away one or more elements of the fire triangle/tetrahedron. Fire safety, at its most basic, is based upon the principle of keeping fuel sources and ignition sources separate Not all fires are the same, and they are classified according to the type of fuel that is burning. If you use the wrong type of fire extinguisher on the wrong class of fire, you can, in fact, make matters worse. It is therefore very important to understand the four different fire classifications. Class A - Wood, paper, cloth, trash, plastics Solid combustible materials that are not metals. (Class A fires generally leave an Ash.) Class B - Flammable liquids: gasoline, oil, grease, acetone Any non-metal in a liquid state, on fire. -

Problems with Flashover

FIRE INVESTIGATION (65758) PROBLEMS WITH FLASHOVER Written by: Anna Katarzyna Kraszewski University Of Technology, Sydney April, 1998 Student Number: 950 63234 Lecturer: A/Prof Wal Stern CONTENTS PAGE SECTION NAME PAGE NUMBER Abstract. i Introduction. , . i Describing The Phenomenon Of Flashover. 1 1 l Incipient/Beginning Stage ............... 1 l Progressive/Free-Burning Stage. ..... l Smouldering Stage ..................... 2 Types Of Flashovers . 3 3 l Radiation Induced Flashovers ......... 3 l Ventilation Induced Flashovers ...... Discussion.. 3 Problems With Flashover . ..I 3 l High Temperatures Involved With Flashovers . 4 l Speed Of The Spread Of Flashover.. l Flashover And Arson.. 5 l Further Training And Education.. 7 l The Question Of Whether To Ventilate Or Not.. 8 Conclusion. , . 9 References. 10 Appendix A.. 11 PROBLEMS WITH FLASHOVER APRIL, 1998 FIRE INVESTIGATION, 65758 ABSTRACT Flashover is defined as “a transition phase in the development of a contained fire in which surfaces exposed to thermal radiation reach ignition temperature more or less simultaneously and fire spreads rapidly throughout the space”. The occurrence of flashover is an extreme form of fire behaviour. The various studies which have been made on the subject of flashover to learn what exactly causes flashover and how to fight them, have only recently commenced to be understood. For fire investigators, flashover is a ‘new reality’ which they have to consider in their work. The following diagram shows the various stages in a typical room fire sequence. 1) When a fire is started on a chair, heat is given off by the fire decomposes the foam / fabric of the chair faster than the chair will burn. -

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems OSHA 3256-09R 2015 Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 “To assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women; by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the States in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; by providing for research, information, education, and training in the field of occupational safety and health.” This publication provides a general overview of a particular standards- related topic. This publication does not alter or determine compliance responsibilities which are set forth in OSHA standards and the Occupational Safety and Health Act. Moreover, because interpretations and enforcement policy may change over time, for additional guidance on OSHA compliance requirements the reader should consult current administrative interpretations and decisions by the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission and the courts. Material contained in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced, fully or partially, without permission. Source credit is requested but not required. This information will be made available to sensory-impaired individuals upon request. Voice phone: (202) 693-1999; teletypewriter (TTY) number: 1-877-889-5627. This guidance document is not a standard or regulation, and it creates no new legal obligations. It contains recommendations as well as descriptions of mandatory safety and health standards. The recommendations are advisory in nature, informational in content, and are intended to assist employers in providing a safe and healthful workplace. The Occupational Safety and Health Act requires employers to comply with safety and health standards and regulations promulgated by OSHA or by a state with an OSHA-approved state plan. -

The Rising Cost of Wildfire Protection

A Research Paper by The Rising Cost of Wildfire Protection Ross Gorte, Ph.D. Retired Senior Policy Analyst, Congressional Research Service Affiliate Research Professor, Earth Systems Research Center of the Earth, Oceans, and Space Institute, University of New Hampshire June 2013 The Rising Cost of Wildfire Protection June 2013 PUBLISHED ONLINE: http://headwaterseconomics.org/wildfire/fire-costs-background/ ABOUT THIS REPORT Headwaters Economics produced this report to better understand and address why wildfires are becoming more severe and expensive. The report also describes how the protection of homes in the Wildland-Urban Interface has added to these costs and concludes with a brief discussion of solutions that may help control escalating costs. Headwaters Economics is making a long-term commitment to better understanding these issues. For additional resources, see: http://headwaterseconomics.org/wildfire. ABOUT HEADWATERS ECONOMICS Headwaters Economics is an independent, nonprofit research group whose mission is to improve community development and land management decisions in the West. CONTACT INFORMATION Ray Rasker, Ph.D. Executive Director, Headwaters Economics [email protected] 406 570-7044 Ross Gorte, Ph.D.: http://www.eos.unh.edu/Faculty/rosswgorte P.O. Box 7059 Bozeman, MT 59771 http://headwaterseconomics.org Cover image “Firewise” by Monte Dolack used by permission, Monty Dolack Gallery, Missoula Montana. TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................. -

Federal Funding for Wildfire Control and Management

Federal Funding for Wildfire Control and Management Ross W. Gorte Specialist in Natural Resources Policy July 5, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33990 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Federal Funding for Wildfire Control and Management Summary The Forest Service (FS) and the Department of the Interior (DOI) are responsible for protecting most federal lands from wildfires. Wildfire appropriations nearly doubled in FY2001, following a severe fire season in the summer of 2000, and have remained at relatively high levels. The acres burned annually have also increased over the past 50 years, with the six highest annual totals occurring since 2000. Many in Congress are concerned that wildfire costs are spiraling upward without a reduction in damages. With emergency supplemental funding, FY2008 wildfire funding was $4.46 billion, more than in any previous year. The vast majority (about 95%) of federal wildfire funds are spent to protect federal lands—for fire preparedness (equipment, baseline personnel, and training); fire suppression operations (including emergency funding); post-fire rehabilitation (to help sites recover after the wildfire); and fuel reduction (to reduce wildfire damages by reducing fuel levels). Since FY2001, FS fire appropriations have included funds for state fire assistance, volunteer fire assistance, and forest health management (to supplement other funds for these three programs), economic action and community assistance, fire research, and fire facilities. Four issues have dominated wildfire funding debates. One is the high cost of fire management and its effects on other agency programs. Several studies have recommended actions to try to control wildfire costs, and the agencies have taken various steps, but it is unclear whether these actions will be sufficient. -

Development of a Portable Flashover Predictor (Fire-Ground Environment Sensor System) FEMA AFG 2008 Scientific Report

WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE Development of a Portable Flashover Predictor (Fire-Ground Environment Sensor System) FEMA AFG 2008 Scientific Report David Cyganski, WPI Electrical and Computer Engineering Dept. R. James Duckworth, Electrical and Computer Engineering Dept. Kathy Notarianni, WPI Fire Protection Engineering Dept. 12/17/2010 Note: This report is part of the Performance Report Narrative - it will be made into at least two journal articles to be submitted for publication An AFG 2008 award supported a science and engineering effort towards development of an integrated Firefighter Locator and Environmental Monitor to provide real-time flashover warning and advanced situational awareness. The goal of the one year effort was evaluation of the feasibility and impact of a new flashover warning technology. The program was designed to balance the tradeoffs between the underlying physics of ideal flashover prediction and the requirements of practical field implementation to ultimately offer firefighters a tool to save lives and enable more efficient firefighting tactics. The project included an integration effort in which the flashover prediction information was fused with a data stream from a system previously developed by WPI under AFG 2006 which provided simultaneous firefighter location and physiological information. This report focuses upon the basic scientific effort to understand the relationship between certain observables on the fireground and the event of flashover, followed by the engineering of a portable device that provides significant warning of the impending event of flashover. PART 1: Time of Flashover Estimation from Ceiling Temperature Measurements 1. Flashover Flashover is the term used to describe a phenomenon where a fire burning locally transitions rapidly to a situation where the whole room is burning, causing a rapid increase in the size and intensity of the fire. -

Session 611 Fire Behavior Ppt Instructor Notes

The Connecticut Fire Academy Unit 6.1 Recruit Firefighter Program Chapter 6 Presentation Instructor Notes Fire Behavior Slide 1 Recruit Firefighter Connecticut Fire Academy – Recruit Program 1 Slide 2 © Darin Echelberger/ShutterStock, Inc. CHAPTER 6 Fire Behavior Connecticut Fire Academy – Recruit Program Slide 3 Some have said that fires in modern furnished Fires Are Not Unpredictable! homes are unpredictable • A thorough knowledge of fire behavior will help you predict fireground events Nothing is unpredictable, firefighters just need to know what clues to look for Connecticut Fire Academy – Recruit Program Slide 4 Connecticut Fire Academy Recruit Program CHEMISTRY OF COMBUSTION Connecticut Fire Academy – Recruit Program 1 of 26 Revision: 011414 The Connecticut Fire Academy Unit 6.1 Recruit Firefighter Program Chapter 6 Presentation Instructor Notes Fire Behavior Slide 5 A basic understanding of how fire burns will give a Chemistry firefighter the ability to choose the best means of • Understanding the • Fire behavior is one of chemistry of fire will the largest extinguishment make you more considerations when effective choosing tactics Fire behavior and building construction are the basis for all of our actions on the fire ground Connecticut Fire Academy – Recruit Program Slide 6 What is Fire? • A rapid chemical reaction that produces heat and light Connecticut Fire Academy – Recruit Program Slide 7 Types of Reactions Exothermic Endothermic • Gives off heat • Absorbs heat Connecticut Fire Academy – Recruit Program Slide 8 Non-flaming -

Occupational Risks and Hazards Associated with Firefighting Laura Walker Montana Tech of the University of Montana

Montana Tech Library Digital Commons @ Montana Tech Graduate Theses & Non-Theses Student Scholarship Summer 2016 Occupational Risks and Hazards Associated with Firefighting Laura Walker Montana Tech of the University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.mtech.edu/grad_rsch Part of the Occupational Health and Industrial Hygiene Commons Recommended Citation Walker, Laura, "Occupational Risks and Hazards Associated with Firefighting" (2016). Graduate Theses & Non-Theses. 90. http://digitalcommons.mtech.edu/grad_rsch/90 This Non-Thesis Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Montana Tech. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses & Non-Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Montana Tech. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Occupational Risks and Hazards Associated with Firefighting by Laura Walker A report submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Industrial Hygiene Distance Learning / Professional Track Montana Tech of the University of Montana 2016 This page intentionally left blank. 1 Abstract Annually about 100 firefighters die in the line duty, in the United States. Firefighters know it is a hazardous occupation. Firefighters know the only way to reduce the number of deaths is to change the way the firefighter (FF) operates. Changing the way a firefighter operates starts by utilizing traditional industrial hygiene tactics, anticipating, recognizing, evaluating and controlling the hazard. Basic information and history of the fire service is necessary to evaluate FF hazards. An electronic survey was distributed to FFs. The first question was, “What are the health and safety risks of a firefighter?” Hypothetically heart attacks and new style construction would rise to the top of the survey data. -

Prescribed Fire: the Fuels Component

FORESTRY Prescribed Fire: The Fuels Component ► In this second of a four-part series, you will learn the importance of the fuel component in prescribed fire. A common science experiment in grade school is to light a candle, place a glass jar over the candle, and watch the flame go out as the oxygen is consumed. This demonstrates the fire triangle of heat, oxygen, and fuel (figure 1). A prescribed fire is a working example of the principles of the fire triangle. In conducting a prescribed fire, you are either working to move a fire across the land or working to extinguish a fire. In either case, good fire lines are critical for containing the fire within a specific area (figure 2). Fire lines remove the fuel side of the fire triangle. Without the fuel, there is no heat and the fire goes out. Figure 1. The three components needed for a fire to occur are oxygen, heat, and fuel. These make up what is called the fire triangle. Remove one of the Fuel Components sides from this triangle and a fire cannot occur or will be extinguished. The way a fire burns depends on a number of Fuel Volume characteristics of the fuel. An often forgotten component The volume of fuel in the area affects the behavior of is the predominant species of the fuel. Not all grasses the fire and the amount of smoke it produces. Large burn the same; neither do all hardwood leaves or even volumes of fuel pose a significant risk for creating a pine needles. -

ASEAN Guidelines on Peatland Fire Management

ASEAN GUIDELINES ON PEATLAND FIRE MANAGEMENT 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 6 INTEGRATED FIRE MANAGEMENT .................................................................. 6 RESOURCE ALLOCATION .............................................................................. 7 HYDROLOGICAL MANAGEMENT .................................................................... 8 ......................................................................................... 9 POLICY AND REGULATION ............................................................................ 9 PEATLAND FIRE PREVENTION MEASURES……………………………………………………..10 INFORMATION & KNOWLEDGE ..................................................................101 PLANNING AND COORDINATION .................................................................. 12 RESOURCES ............................................................................................. 13 PUBLIC COMMUNICATIONS ........................................................................ 15 ................................................................................... 18 POLICIES AND REGULATIONS ....................................................................... 18 INFORMATION & KNOWLEDGE .................................................................... 19 PLANNING AND COORDINATION .................................................................. 21 RESOURCES ............................................................................................ -

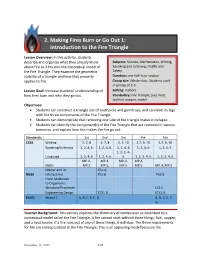

2. Making Fires Burn Or Go out 1: Introduction to the Fire Triangle

2. Making Fires Burn or Go Out 1: Introduction to the Fire Triangle Lesson Overview: In this activity, students describe and organize what they already know Subjects: Science, Mathematics, Writing, about fire so it fits into the conceptual model of Speaking and Listening, Health and the Fire Triangle. They examine the geometric Safety stability of a triangle and how that property Duration: one half-hour session applies to fire. Group size: Whole class. Students work in groups of 2-3. Lesson Goal: Increase students’ understanding of Setting: Indoors how fires burn and why they go out. Vocabulary: Fire Triangle, fuel, heat, ignition, oxygen, model Objectives: • Students can construct a triangle out of toothpicks and gumdrops, and can label its legs with the three components of the Fire Triangle. • Students can demonstrate that removing one side of the triangle makes it collapse. • Students can identify the component(s) of the Fire Triangle that are removed in various scenarios, and explain how this makes the fire go out. Standards: 1st 2nd 3rd 4th 5th CCSS Writing 2, 7, 8 2, 7, 8 2, 7, 10 2,7, 9, 10 2,7, 9, 10 Speaking/Listening 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, Language 1, 2, 4, 6 1, 2, 4, 6 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 MP.4, MP.4, MP.4, MP.4, Math MP.5 MP.5, MP.5 MP.5 MP.4, MP.5 Matter and Its PS1.A, NGSS Interactions PS1.B PS1.B From Molecules to Organisms: Structure/Processes LS1.C Engineering Design ETS1.B ETS1.B EEEGL Strand 1 A, B, C, E, F, G A, B, C, E, F, G Teacher Background: This activity explores the chemistry of combustion as described by a conceptual model called the Fire Triangle.