Distribution, Power and Networks in Financial Markets of Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SECRETARIAT Pakistan Stock Brokers Association PRESS

PRESS RELEASE July 15, 2021 “FILING OF CONSTITUTIONAL PETITION IN THE HIGH COURT OF SINDH BY THE PAKISTAN STOCK BROKERS ASSOCIATION AGAINST FUTURES ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA NOTIFIED BY THE PAKISTAN STOCK EXCHANGE” (Thursday, July 15, 2021, Karachi): Pakistan Stock Brokers Association (PSBA) filed a Constitutional Petition (CP) in the High Court of Sindh against the Futures Eligibility Criteria, for Selection of Securities Eligible for Trading in Deliverable Futures Contract (DFC) and Cash Settled Futures Contract (CSF) Market, as notified by the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX), with prior approval of the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP). The first hearing of the said CP was held today at the Sindh High Court. The Honorable Court has very kindly granted interim order to make the concerned notice inoperative to the extent that it discriminates against entities which have obtained stay order from the Court. Among other grounds, it was pleaded before the Honorable Court that the Respondents have acted in violation of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973, as they have no right to restrict any specific securities eligible for trading in the deliverable futures contract and cash settled futures contract markets, under the guise that such entities have invoked their constitutional right of protection by assailing any illegal action in a court of law. The PSBA will remain dedicated to the betterment of the economy, promotion of the stock brokerage industry, and protection of the rights of its members. ----------------------------------------------------------xxxxxxxxxxxx---------------------------------------------------------- SECRETARIAT Pakistan Stock Brokers Association . -

PAKISTAN STOCK EXCHANGE LIMITED List of Office(S)/Branch Office(S)

PAKISTAN STOCK EXCHANGE LIMITED List of Office(s)/Branch office(s) TREC # Name of TRE Corporate Office/ Address Manager Certificate Holder Branch Office 001 Altaf Adam Securities (Private) Limited Corporate Office Suit No. 803, 8th Floor, Altaf Adam Stock Exchange Building, Stock Exchange Road OA- 001 Karachi 021-32440242, 32440243 021-32427768 003 Muhammad Hussain Ismail Securities (Private) Limited Corporate Office Room No. 113, 3rd Floor Ashraf Muhammad Stock Exchange Building, Stock Exchange Road, Hussain OA- 003 Karachi. 021-32417326, 32421005 006 Sherman Securities (Pvt.) Ltd. Corporate Office 501-502, 5th Floor, Muhammed Samin Continental Trade Centre, Block-VIII, Clifton OA- 006 Karachi 021-35302914, 35302936 021-5363554 Branch Office Room No.124, 3rd Floor, Muhammad Arsalan Stock Exchange Building, Stock Exchange Road BOA- 006/01 Karachi 021-2426002 021-2417472 007 Amanah Investments Limited Corporate Office Room No. 123, 3rd Floor, Abdul Wahab Omar Stock Exchange Building, Stock Exchange Road, OA- 007 Karachi 021-3246876, 32468767-8 021-32468769 Branch Office AH House 196-A, Block-2 Muhammad Irfan PECHS, Shah Abdul Latif Road, BOA- 007/01 Karachi 021-32468768-69 008 Optimus Capital Management (Pvt.) Ltd. Corporate Office Plot No. 13-C, Stadium Lane-2, DHA, Phase-V, Muhammad Ovais Stadium, Commercial Area-5, Khadda Market Ahsan OA- 008 Karachi 021-35296888 021-35296957 Thursday, January 28, 2021 Page 1 of 53 TREC # Name of TRE Corporate Office/ Address Manager Certificate Holder Branch Office 010 Sakarwala Capital Securities (Pvt.) Ltd. Corporate Office Room No. 114, 3rd Floor, Ghulam Mujtaba Stock Exchange Building, Stock Exchange Road, Sakarwala OA- 010 Karachi 021-32411998, 32419732, 32428302 021-32428303 Branch Office Room No. -

Topline Market Review P

Pakistan Weekly January 12, 2018 REP‐057 Topline Market Review Gains erode as profit taking ensues KSE‐100 Index +1.0 % WoW; Weekly net FIPI US$26mn Topline Research Best Local Brokerage House [email protected] Brokers Poll 2011-14, 2016-17 Tel: +9221‐35303330, Ext: 133 Topline Securities, Pakistan www.jamapunji.pk Best Local Brokerage House 2015-16 Index gains 1% in outgoing week as profit taking ensues Market Weekly Data KSE Volume & Value KSE‐100 Index 42,933.72 (Shares mn) Volume Value (US$mn) 330 150 1‐Week Change (%) 1.0% 260 Market Cap (Rs tn) 8.9 106 190 1‐Week Change (%) 0.2% 63 Market Cap (US$ bn) 80.6 120 1‐Week Change (%) 0.2% 50 20 18 18 18 18 18 ‐ ‐ 1‐Week Avg. Daily Vol (shares mn) 276.4 ‐ ‐ ‐ n n n n n aa aa aa aa aa J J J J J ‐ ‐ 1‐Week Avg. Daily Value (Rs bn) 12.2 ‐ ‐ ‐ 9 8 1‐Week Avg. Daily Value (US$ mn) 110.2 10 11 12 Source: PSX Source: PSX Outgoing week saw the culmination of the Santa Clause rally which commenced on December 20, 2017 and peaked on Jan 10, 2018 with a net gain of 14%. Since then index has had red two sessions correcting 2%/697pts, which has trimmed weekly gains to 1%/410pts with the index closing the week at 42,934pts level. Going forward, equities maybe further pressured as agitation movement by opposition parties begin on Jan 17 to protest against the Model Town. PtiitiParticipation idimproved siifitlignificantlyasprofitswerebkdbooked, average volumes idincreased 30% WWWoW whilevalue rose 44%. -

CONTENTS FUND INFORMATION Management Company Faysal Asset Management Limited Fund Information 2 Board of Directors of the Management Company Mr

Quarter and Nine months ended March 31, 2007 Quarter and Nine months ended March 31, 2007 CONTENTS FUND INFORMATION Management Company Faysal Asset Management Limited Fund Information 2 Board of Directors of the Management Company Mr. Farook Bengali, Chairman Mr. Salman Haider Sheikh, Chief Executive Officer Mission Statement 3 Mr. Hassan Mohamed Mahmood, Director Mr. Mohammad Iqbal, Director Mr. Shahid Waqar Mahmood, Director Mr. Feroz Rizvi, Director Report of the Directors of the Management Company 4 Mr. Iqbal Alimohamed, Director Mr. Aqeel Karim Dhedhi, Director CFO of the Management Company Statement of Assets and Liabilities 6 Mr. Muhammad Shakeel Musani Company Secretary of the Management Company Mr. M. Siddique Memon Income Statement 7 Audit Committee Mr. Iqbal Alimohamed, Chairman Mr. Mohammad Iqbal, Member Distribution Statement 8 Mr. Shahid Waqar Mahmood, Member Mr. Feroz Rizvi, Member Trustee Statement of Movement in Unit Holders’ Funds 9 Central Depository Company of Pakistan Limited 8th Floor, Karachi Stock Exchange Building, Stock Exchange Road, Karachi-74000 Cash Flow Statement 10 Bankers to the Fund Faysal Bank Limited MCB Bank Limited Bank Alfalah Limited Notes to the Financial Statements 11 Habib Metropolitan Bank Limited Atlas Bank Limited Bank of Punjab Limited Auditor A.F. Ferguson & Co., Chartered Accountants Legal Advisor Mohsin Tayebaly & Co. Barristers & Advocates, Corporate legal Consultants, 2nd Floor, Dime Centre, BC-4, Block-9, KDA-5, Clifton, Karachi. Registrar Gangjees Registrar Services (Pvt) Limited Room -

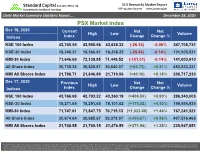

PSX Market Index

Standard Capital Securities (Pvt.) Ltd. SCS Research | Market Report Committed to intelligent investing REP-033 also log onto www.jamapunji.pk Daily Market Summary Statistics Report…. December 18, 2020 REP-033 also log onto PSX Market Indexwww.jamapunji.pk Dec 18, 2020 Current Net Net High Low Volume Indices Index Change Change % KSE 100 Index 43,740.55 43,955.56 43,638.33 (-26.14) -0.06% 247,708,731 KSE-30 Index 18,246.21 18,366.81 18,208.25 (-25.43) -0.14% 131,905,521 KMI-30 Index 71,646.60 72,139.95 71,449.52 (-101.01) -0.14% 141,003,610 All Share Index 30,738.36 30,825.87 30,640.07 (+63.72) +0.21% 482,533,331 KMI All Shares Index 21,788.71 21,846.89 21,719.06 (+40.16) +0.18% 208,717,230 Dec 17, 2020 Previous Net Net High Low Volume Indices Index Change Change % KSE 100 Index 43,766.69 43,793.22 43,360.19 (+406.50) +0.93% 286,340,005 KSE-30 Index 18,271.64 18,291.65 18,101.62 (+170.02) +0.93% 149,554,934 KMI-30 Index 71,747.61 71,847.75 70,715.13 (+1,032.48) +1.44% 167,241,521 All Share Index 30,674.64 30,685.67 30,378.97 (+295.67) +0.96% 497,516,465 KMI All Shares Index 21,748.55 21,769.15 21,476.59 (+271.96) +1.25% 239,947,851 Disclaimer: This report has been prepared by Standard Capital Securities (Pvt) Ltd. -

The Effect of Uncertainty on Stock Returns and Risk-Returns (Volatility) Relationship Across Military and Democratic Regimes in Pakistan

Marketing and Branding Research 7(2020) 24-46 Marketing and Branding Research WWW.CIKD.CA The Effect of Uncertainty on Stock Returns and Risk-returns (Volatility) Relationship Across Military and Democratic Regimes in Pakistan Zareen Zafar1*, Danish Ahmed Siddiqui2 1, 2Karachi University Business School, University of Karachi, Pakistan ABSTRACT Keywords: This research includes empirical results in making a consistent understanding of investor Pakistan Stock Market, Stock sagacity, investment returns, and behavioral stock market performance in the behavioral Returns, Risk Returns, finance trend theoretical context. The data were collected using a long range of Returns data Military Regieme, Pakistan's stock market Since June 1994 to December 2018 on the two economic segments Democratic Regieme, known as the Military Period (1999-2008 and 2009-2018). Quantile Regression (QR) and Ordinary Least Square, Ordinary Least Square (OLS) carried out on future returns and risk-returns (volatility) where Quantile Regression, the independent variables Consumer Price Index (CPI), Gross Domestic Product (GDP), Uncertainty index Money Market Rate (MMR), Discount Rate (DR) and Pakistan's Uncertainty Index were taken at annual data base. The findings indicated that DR and past returns significantly impact future Received returns. Other factors such as GDP, inflations, MMR and conditions of instability, however, 14 October 2020 had no major impact on returns. With regard to the military process, all variables such as past Received in revised form returns, GDP, discount and cash market levels, as well as volatility, had a major return impact. 26 October 2020 Whereas in the process of democracy, no macroeconomic factor affected those returns. With regard to volatility, CPI appeared to be the only factor that positively impacted the volatility Accepted of share prices, as well as each of the two phases while all other factors had no significant 26 October 2020 effect overall. -

Pakistan Stock Market Reaction to Covid-19

PAKISTAN STOCK MARKET REACTION TO COVID-19 HAMID HUSSAIN1 The COVID-19 outbreak could go down as a significant illustration of an overlooked danger in history. Much of the concern of corporate decision-makers and policymakers has centered on mainstream market risk outlets and the urgent climate change problem. Major personal life disturbances are happening, for example curfew-like situations in Pakistan and in other countries. Besides the acute disasters of death and illness, there is pervasive apprehension (leading, for instance, to mass purchase of daily goods). The potential economic influence of COVID-19 remains somewhat unpredictable, as it is not clear regarding the propagation of the epidemic, its extent and mortality rate, the policy responses and human behavior. Economists anticipate the COVID-19 to reduce global economic development by about 0.15 percentage points in 2020, translated into about $135 billion in postponed or unproduced products and services. This year's effects would be guided by three things: first, how quickly the virus travels and how long it lasts; secondly, how much concern affects travel, consumer buying, production, and trade; and finally what steps policymakers take to avoid the spread of the virus and improve productivity. In this case, the equity market provides a beneficial opportunity to examine, which companies find creditors to be especially impacted by the direct and indirect consequences of the virus outbreak and which companies may not be impaired. In this way, the equity exchange offers a constantly monitored and welcomed overview of what the markets think may eventually be the economic effect of the epidemic. -

Investment in Pakistan.Pdf

KPMG Taseer Hadi & Co. Chartered Accountants Investment in Pakistan © 2020 KPMG Taseer Hadi & Co., a Partnership firm registered in Pakistan and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. © 2020 KPMG Taseer Hadi & Co., a Partnership firm registered in Pakistan and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. Investment in Pakistan Foreword Investment in Pakistan is a publication prepared by KPMG Pakistan to provide information on a number of subjects relevant for investment planning or doing business in Pakistan. The guide includes an overview of the economy and a summary of performance of identified sectors which could be of interest for investors and provides a summary of the rules, regulations and tax laws applicable in Pakistan. Although covering many relevant areas, it should not be considered as exhaustive since it has not been designed to provide complex and detailed information required for decision- making in relation to investments. This publication incorporates the regulations effective as of 31 October 2019. For our latest publications please browse our web site; www.kpmg.com.pk © 2020 KPMG Taseer Hadi & Co., a Partnership firm registered in Pakistan and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), -

PAKISTAN STOCK EXCHANGE LIMITED List of Office(S)/Branch Office(S)

PAKISTAN STOCK EXCHANGE LIMITED List of Office(s)/Branch office(s) TREC # Name of TRE Corporate Office/ Address Manager Certificate Holder Branch Office 001 Altaf Adam Securities (Private) Limited Corporate Office Suit No. 803, 8th Floor, Altaf Adam Stock Exchange Building, Stock Exchange Road OA- 001 Karachi 021-32440242, 32440243 021-32427768 003 Muhammad Hussain Ismail Securities (Private) Limited Corporate Office Room No. 113, 3rd Floor Ashraf Muhammad Stock Exchange Building, Stock Exchange Road, Hussain OA- 003 Karachi. 021-32417326, 32421005 006 Sherman Securities (Pvt.) Ltd. Corporate Office 501-502, 5th Floor, Muhammed Samin Continental Trade Centre, Block-VIII, Clifton OA- 006 Karachi 021-35302914, 35302936 021-5363554 Branch Office Room No.124, 3rd Floor, Muhammad Arsalan Stock Exchange Building, Stock Exchange Road BOA- 006/01 Karachi 021-2426002 021-2417472 007 Amanah Investments Limited Corporate Office Room No. 123, 3rd Floor, Abdul Wahab Omar Stock Exchange Building, Stock Exchange Road, OA- 007 Karachi 021-3246876, 32468767-8 021-32468769 Branch Office AH House 196-A, Block-2 Muhammad Irfan PECHS, Shah Abdul Latif Road, BOA- 007/01 Karachi 021-32468768-69 008 Optimus Capital Management (Pvt.) Ltd. Corporate Office Plot No. 13-C, Stadium Lane-2, DHA, Phase-V, Muhammad Ovais Ahsan Stadium, Commercial Area-5, Khadda Market OA- 008 Karachi 021-35296888 021-35296957 Thursday, April 1, 2021 Page 1 of 53 TREC # Name of TRE Corporate Office/ Address Manager Certificate Holder Branch Office 010 Sakarwala Capital Securities (Pvt.) Ltd. Corporate Office Room No. 114, 3rd Floor, Room No. 605-606, 6th Floor, Ghulam Mujtaba Stock Exchange Building, Stock Exchange Road, Sakarwala OA- 010 Karachi 021-32411998, 32419732, 32428302 021-32428303 Branch Office Room No. -

Formerly: Karachi Stock Exchange Limited) Stock Exchange Building, Stock Exchange Road, Karachi-74000, Phones: 111-001-122

PAKISTAN STOCK EXCHANGE LIMITED (Formerly: Karachi Stock Exchange Limited) Stock Exchange Building, Stock Exchange Road, Karachi-74000, Phones: 111-001-122 CRITERIA FOR SELECTION OF TOP 25 COMPANIES FOR THE YEAR 2016 1) Prerequisites for Selection of Top Companies: a) A minimum distribution of 30% (including at least 15% cash dividend) for the year; b) The Shares of the company are traded 50% of the total trading days during the year c) The company should not be in the Defaulters’ Segment of the Exchange or trading in its shares has not been suspended on account of violation of Listing of Companies & Securities Regulations of the Exchange during the year. 2) The Companies that Qualify above Prerequisites will be selected on the Basis of Highest Marks Obtained as per the following Criteria: a) Capital Efficiency: (i) Shareholders Return on Equity (on the basis of before tax profit) 15% (ii) Ratio of Capital Expenditure to Total Assets 3% (iii) Change in Market Value Added (MVA of a year in the difference 2.5% between Market Value minus Book Value for that year.) b) Dividend Distribution (including Bonus) (i) Total Distribution out of Current Year’s Profit only. (In case 10% dividend/bonus is paid out of prior year’s earnings/reserves, than the dividend/bonus shall be adjusted proportionately) (ii) Payout Ratio (DPS / EPS) 10% c) Growth in Operating Revenue 6% Change in EBITDA Margin (Operating margin) in absolute terms 6% d) Free-Float of Shares 10% Free-Float of shares as a percentage of total shares outstanding e) Turnover of Shares -

Capital Market

7 Capital Market 7.1 Introduction Pakistan’s capital market showed a mixed trend during FY01 (see Table7.1). The benchmark KSE- 100 index shed 10.1 percent since the beginning of FY01 and closed the year at 1366.4. This downturn can be attributed to a host of factors including the lack of concrete progress on privatization, uncertain investor confidence, the continuous depreciation of the Rupee and friction between SECP and the bourses. While equity market remained bearish, the corporate bond market showed encouraging movements. The growth in this market was encouraging, as ten new TFCs issues were floated during FY01 alone, compared to ten in the last five fiscal years. 7.2 Stock Market Performance The Karachi Stock Exchange (KSE) maintained Table 7.1: Key Indicators of Capital Market its dominance in the country (see Table 7.1). FY99 FY00 FY01 Karachi Stock Exchange Primary market activities in KSE remained KSE-100 index 1054.7 1520.7 1366.4 slow, as only four new companies (with paid up SBP General index 106.4 128.8 118.7 capital of Rs 3.6 billion), were listed during Paid up capital (billion Rs) 215.0 229.3 239.9 FY01. Similarly, only two companies were Turnover of shares (billion #) 25.5 48.1 29.2 floated on the Lahore stock exchange, of which Lahore Stock Exchange Hubco was already subscribed. Like the KSE- LSE-101 index 288.9 372.0 273.2 100 index, the LSE-101 also declined by 98.8 Turnover of shares (billion #) 9.8 16.4 7.8 Paid up capital (billion Rs) 186.9 207.7 226.2 points (26.5 percent) to 273.2 by end-FY01. -

A Case of Non-Financial Firms Listed at Pakistan Stock Exchange Textile Sector

P a g e | i INTRODUCTION Iqra Journal of Business & Management is a peer reviewed journal initiated by the Business Administration Department, Iqra National University, Peshawar, Pakistan in year 2017. The aim of the journal is to publish latest research related to the field of management, business administration, marketing, finance, entrepreneurship and so on. The main contributors of the journal are academics, researchers, practitioners, consultants, and undergraduate and postgraduate students. The journal has a diverse advisory board consist of experts from developed countries as well as well-known universities at national level. The journal provides a platform for sharing diverse research work in the field and aims to reduce the gap between the industry and academia. The journal is abstracted and indexed in high ranking abstracting and indexing agencies. The journal does not charge any fee to authors and is freely available to the readers through its web site. AIMS AND SCOPE The Iqra Journal of Business & Management provides an excellent outlet for research and scholarship on management-related themes and topics. The journal contributions comes from all over the country as well as from abroad, and include empirical and methodological articles across the full range of business and management disciplines including; • General management • General administration • Accounting and finance • Human Resource Management • Marketing and supply chain management • Strategic Management • Operations Management • Entrepreneurship • Corporate Social Responsibility • Public Sector Management • Organizational Behavior • Business Ethics • Research methods Iqra Journal of Business & Management (IJBM) Volume2, Issue 1, 2018 P a g e | ii CHIEF EDITOR MESSAGE Pakistan is going through a transitional period having long lasting impact on its economy, politics, culture, and social structure of the society.